The Skeptical Virtue of Seriously Just Being Quiet

Recently I attended a dinner party as the guest of a new friend among people who’ve known each other for decades. After dinner, the conversation turned to a story that had puzzled and intrigued the hosts. They were excited to share a YouTube video about a black leopard whose behavior was allegedly improved through the intervention of an “animal communicator” (pet psychic).

Cover art for Junior Skeptic #66, bound inside Skeptic Vol. 23, No. 1. Illustration by Jacob Dewey.

Now, this is a literate, philosophical bunch. They like debating, speculating, and devil’s advocacy, so they didn’t much mind that my friend found the claims of the video preposterous. After some lively verbal fencing, she turned to me in exasperation and said, “We have a professional skeptic right here! Daniel, you write about this stuff for a living. What do you think?”

Well, I had thoughts. But I said the minimum: that I hadn’t yet looked professionally at the specific topic of pet psychics, and that the video was a constructed narrative whose claims we should neither accept nor reject without checking. (Then I went away and actually did spend weeks researching and writing a lengthy critique of pet psychics for the pages of Junior Skeptic.)

What I said was true. But it’s also true that I might have contributed more to that conversation in other periods of my life.

TAGS: communication, paranormal, scientific skepticism, skepticismSKEPTIC INVESTIGATES

Is the Earth Flat?

Recent news stories,1 celebrity endorsements, and Google search trends2 have highlighted an apparently growing conspiracy theory belief that the Earth is not a globe, but instead a flat disc. According to believers, government forces promote a completely fictitious model of the cosmos in order to conceal the true nature of the Earth. Are these claims true?

No. The Earth is Round

The evidence for a spherical Earth is overwhelming.3 Most obviously, there are many thousands of images and videos of the Earth from space, including a continually changing live stream view of the globe from the International Space Station—not to mention all the astronauts who have personally seen the Earth from orbit. Flat Earthers claim that all images of the globe are fraudulent inventions, and all testimony from astronauts is false. It is unreasonable to dismiss all of the evidence from the entire history of space exploration, especially when there is zero evidence for a decades-long “globularist” conspiracy. However, we do not need to rely on evidence from modern space agencies to confirm the roundness of the Earth for ourselves.

Portions of this article appeared previously in Daniel Loxton’s detailed history of the Flat Earth movement in Junior Skeptic #53, bound within Skeptic magazine 19.4 (2014).

The globe has been clearly understood for thousands of years. Indeed, this was one of the first cosmic facts to be worked out correctly by ancient people because evidence of a spherical Earth is visible to the naked eye.

By the time of the philosopher Socrates and his student Plato, many Greeks understood that the Earth could only be a sphere. Sailors would have noticed that the sails of approaching ships appeared before the hulls of the ships became visible because the surface of the sea is slightly curved, like the surface of an enormous ball.4 When you sail toward a ship, island, or lighthouse, their tallest points are the first thing to peek up over the curve of the horizon.

Plato’s student Aristotle offered further “evidence of the senses” to support his own conclusion that the Earth “must necessarily be spherical.” First, there was the evidence of lunar eclipses. When the Moon passes through the shadow of the Earth, that shadow is always the circular shadow of a sphere. Also, Aristotle argued, “our observations of the stars” make it clear “not only that the earth is circular, but also that it is a circle of no great size.” He pointed out that “quite a small change of position to south or north” significantly changes “the stars which are overhead, and the stars seen are different, as one moves northward or southward.” Just as ships can be hidden from view by the curvature of the horizon, so too can the stars.5

The debate about the shape of the Earth has been settled for over two thousand years. An ancient scholar named Eratosthenes—the head of the famous library of Alexandria in Egypt—even correctly approximated the circumference of the Earth using experimental measurements of shadows in two cities and some geometry.6

Despite modern legends about Medieval backwardness, there never was a time when educated people went back to thinking the Earth was flat. Once discovered, the true shape of the globe was too simple and useful a fact to be forgotten. Sailors were reminded of the planet’s roundness every time they climbed a mast to see further over the horizon or looked to the stars to determine their position. By the time of Columbus, his crew and even his critics understood that our world is a globe.7 It had been an established fact for centuries. For example, here’s a passage from the popular astronomy textbook On the Sphere of the World, published over 250 years before Columbus sailed: CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

TAGS: conspiracy theories, flat earth, Skeptic InvestigatesMammoth Mysteries — Part I

In the pages of Junior Skeptic—the engagingly illustrated science and critical thinking publication for younger readers, bound within every issue of Skeptic magazine—we often look at “wild and wooly” mysteries. In Junior Skeptic #60 (2016), we mean that literally; we explore the hidden history of mammoths and mastodons! Enjoy this excerpt from the first couple pages of the Junior Skeptic #60, bound within Skeptic magazine 21.3 (2016), available now in print and digital editions.

The elephant family tree has had many oddly shaped branches. There once existed elephants with four tusks or even tusks shaped like shovels. But fossils of mammoths and mastodons weren’t just surprising—they changed science forever! Indeed, the discovery of these great shaggy prehistoric beasts overturned our understanding of the entire world. How did that happen?

First, before we consider the mammoths, I’d like you to pause for a moment and imagine some of the animals that lived even earlier, during the age of the dinosaurs. Picture these animals living and breathing in their natural environments. What do you see? Perhaps the terrible teeth of CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

TAGS: Junior Skeptic, mammothsThe Complexity of Alien Abduction and the Multidisciplinary Nature of Fringe Claims

Image by Daniel Loxton with Jim W.W. Smith and Jason Loxton

Today I’ll ask a related question: why are skeptics a mixed group of magicians, psychologists, doctors, historians, science popularizers, artists, and so on?

TAGS: alien abduction, scientific skepticism, skepticismFringe Claims: Unified by Neglect, Structural Similarity, and Direct Interconnection

A recent Scientific American blog post raised a very tedious and very old complaint about scientific skepticism—in essence, “Paranormal and pseudoscientific claims are trivial. Why don’t you do something I consider important?” The answer I expressed in my previous post is that fringe beliefs are a significant part of the fabric of human existence, and yes, sometimes important in their own right. Seeking to understand those beliefs is a worthwhile research endeavor.

This brought to mind a more interesting question: why does modern skepticism seek to study such a broad and seemingly heterogeneous group of topics—everything from UFOs to climate denialism to mermaids to quack cancer cures?

Philosopher Austin Dacey posed this latter question in a 2011 article after attending a skeptics conference in Las Vegas (The Amazing Meeting). Adopting “the eye of an anthropologist,” Dacey observed that “the remarkable thing was just how non-obvious, even peculiar is the selection of subjects that characterize contemporary organized skepticism.”1 Skeptics collect dozens, indeed hundreds of fringe topics under our research umbrella while choosing not to focus on other topics we consider unrelated—embracing “a kind of canon,” Dacey noted, that “can appear quite odd and contingent. What is it…that binds together ginkgo biloba and El Chupacabra, cold reading and cosmic fine tuning? Why this canon?”

TAGS: scientific skepticism, scope, scope of skepticism, skepticismBigfoot Versus the Quest for World Peace?

For the entire history of scientific skepticism, folks in our weird and wonderful little field have heard two criticisms offered with metronomic regularity from people who are “skeptical of the skeptics.”1 One is the obvious: “Skeptics are closed-minded!” The other, no less predictable or routine, is my topic today: “Why do you bother with this trivial stuff about pseudoscience and the paranormal? Aren’t there more important things to worry about?”

Yesterday, science writer John Horgan offered the latest example of this second standard criticism in a Scientific American blog post titled “Dear ‘Skeptics,’ Bash Homeopathy and Bigfoot Less, Mammograms and War More” (presented first as a speech last weekend at the Northeast Conference on Science and Skepticism, NECSS, in New York City). Positioning his piece as a critique (“I have to bash skepticism”) from an outsider perspective ( “I don’t belong to skeptical societies. I don’t hang out with people who self-identify as capital-S Skeptics”), Horgan “decided to treat the skeptics skeptically.” He offered a prescription: skeptics should stop patting “each other on the back” and stop wasting our time on the “soft targets” of paranormal and pseudoscientific claims:

TAGS: scientific skepticism, scope of skepticism, skepticismI’m asking you skeptics to spend less time bashing soft targets like homeopathy and Bigfoot and more time bashing hard targets like multiverses, cancer tests, psychiatric drugs and war, the hardest target of all.

I Don’t Know What You Mean

Painting by Daniel Loxton, c.1999. Acrylic on canvas. 24″x36″.

The journal Judgment and Decision Making has stirred considerable interest with a recent paper titled “On the Reception and Detection of Pseudo-Profound Bullshit,” by Pennycook et al (read PDF). The authors conducted four surveys designed to explore differing individual reactions to “seemingly impressive assertions that are presented as true and meaningful but are actually vacuous.” That is, the authors are “interested in the factors that predispose one to become or to resist becoming a bullshittee.”1

Skeptics naturally share this interest.

The studies presented survey participants with vague, conceptually meaningless, buzzword-laden statements and asked them to rate the “relative profundity of each statement on a scale from 1 (not at all profound) to 5 (very profound).” The included statements were generated by two online tools: “The New Age Bullshit Generator” and Wisdomofchopra.com, which “constructs meaningless statements with appropriate syntactic structure by randomly mashing together a list of words used in Deepak Chopra’s tweets (e.g., ‘Imagination is inside exponential space time events’).”2 Some of the studies also included motivational aphorisms, simple factual statements, and actual tweets selected from Chopra’s Twitter feed,3 such as this one:

TAGS: belief, Bullshit!, communication, Deepak Chopra, psychology, scientific skepticismSo… Who ARE You Gonna Call?

Outside of Junior Skeptic (my primary ongoing project) a surprising amount of my professional output—most of my blogging, stage appearances, op-eds (PDF), and interviews—is given over to the oddly controversial argument that my field should exist.

It’s my opinion that “scientific” skepticism should be acknowledged as a distinct field of study with a unique mandate: the critical, science-informed, scholarly examination of paranormal, pseudoscientific, and other fringe claims. Consequently, I’ve rejected (PDF) periodic suggestions that skepticism should shift its focus from fringe topics toward arguably “more important” matters, or that skepticism ought to be subsumed as a side-project within some other sphere (such as “science,” humanism, or atheism).

Colleagues such as Steve Novella, Sharon Hill, Barbara Drescher, and Jamy Ian Swiss (video) often find themselves drawn to such discussions. I tend to agree with these and other traditionalist skeptics about the most suitable scope for scientific skepticism: “testable” (that is, investigable) claims. In addition, I’ve argued that it’s desirable for skeptics to emphasize a specialized core subject matter within that “testable claims” scope: pseudoscience and the paranormal. Not an exclusive concern with fringe claims, mind—that’s more restrictive than I or anyone wants to see—just an ongoing (and historically well-established) emphasis upon claims of that type.

TAGS: ghostbusters, scope of skepticism, skepticismThe Plane Truth: Noted Skeptic’s Newly Published (Posthumous) Book About Flat Earth Theories

Explore Bob Schadewald’s final project, a book on the topic of his most specialized area of skeptical expertise: Flat Earth theories.

I’m very pleased to learn that The Plane Truth, the unfinished final work of skeptical scholarship by the late Robert J. Schadewald (1943–2000), has now been prepared for publication and released online for free. You can read the book in its web version here, where you also find the EPUB ebook version available for download.

During his life, Bob Schadewald was the world’s leading skeptical expert on the history of flat-Earth advocacy. The pseudoscientific notion that the Earth is a flat disk may seem as quaint as it is preposterous, but so-called “Zetetic Astronomy” enjoyed a surprisingly strong period of public prominence in the UK and US during the 19th century—attracting attention from debunkers of the period such as Alfred Russel Wallace1 (see Skeptic Vol. 20, No. 3) and Richard Anthony Proctor, and prompting reflections from later thinkers including George Bernard Shaw and George Orwell. During the 20th century the relative sophistication of Zetetic Astronomy collapsed into muddled conspiracy theories, parody, and ultra-fundamentalist Biblical literalism; nevertheless, flat-Earth advocacy continues to this day.

TAGS: Bob Schadewald, creationism, flat earth, history of skepticism, Lois Schadewald, Robert J Shadewald, skepticismThe 10 Percent Brain Myth

This is an excerpt from Junior Skeptic 37 (published in 2010 inside Skeptic magazine Vol. 15, No. 4), which is a quick ten-page tour of the “Top Ten Busted Myths.” Junior Skeptic is written for (older) children, and does not include endnotes, though I often call out important sources in sidebars or the text of the story itself. However, I’ve included one or two citations here for your interest:

Have you heard that we only use 10 percent of our brains? Imagine what we could accomplish if we could discover how to use that other 90 percent! Could we discover an untapped potential for incredible psychic powers?

There’s only one problem: none of that is true. Humans use every part of our brains.

TAGS: brain, Junior Skeptic, mythology, neuroscience, Steven NovellaA Rope of Sand

If my explorations of skeptical history have revealed an overall theme, it is that things don’t change that much. Always there are scoundrels, scams, and misapprehensions; always there are those who probe mysteries and push back against paranormal fraud. Throughout history, those skeptics have repeatedly reached for the same tactics, claimed the same (scant few) rewards, and faced the same challenges of burnout and cynicism.

Astronomer Richard Anthony Proctor. For general details about Proctor’s life and career, read this brief biographical sketch published in 1874.

English astronomer and science popularizer Richard Anthony Proctor (1837–1888) makes an interesting case study. He weighed in as a skeptic against (surprisingly popular) Flat Earth advocates (see Junior Skeptic 53), quackery, and a range of pseudoscientific ideas connected to astronomy. His debunking book Myths and Marvels of Astronomy was a 19th century version of Phil Plait’s Bad Astronomy. Originally published in 1877 (my copy dates to 1880), Myths and Marvels of Astronomy is available to read for free in several editions online.

TAGS: astronomy, Great Moon Hoax, Richard Anthony Proctor, skeptical historyThe Problematic Process of Cryptozoologification

How did the traditional character of the cannibal ogress Dzunuk’wa come to be claimed by cryptozoologists as a depiction of their hypothesized “Bigfoot” cryptid species? (Kwakwaka’wakw heraldic pole. Carved in 1953 by Mungo Martin, David Martin, and Mildred Hunt. Thunderbird Park at the Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria. Photograph by Daniel Loxton)

My research has often led me to consider how folkloric phenomena are brought under the umbrella of cryptozoology (the largely pseudoscientific “study” of legendary, allegedly “hidden” animals). In this active process, fuzzy abstractions—fluid supernatural conceptions, diverse “saw something weird” events, stories, metaphors, and shifting myths—are distilled down into more-or-less concrete hypothetical “species” of cryptids. For want of a better term, I’ve started to think of this cultural crystallization process as “cryptozoologification.”1 And it’s a bit of a problem. When the mists of folklore are reified as the discrete objects of cryptozoological pursuit, something is not only lost, but actively discarded.

TAGS: cryptids, cryptozoology, culture, legends/folklore, monstersThe Odds Must Be Crazy?

Anna Maltese (left) presents Daniel Loxton with a bizarre coincidence after his talk at The Amazing Meeting 2014, while his wife Cheryl Hebert looks on. (Photograph by David Patton. Used with permission.)

There are few experiences so striking—so deeply imbued with apparent meaning—as a remarkable coincidence. But when is a coincidence genuinely meaningful rather than merely unexpected? And when is it neither, but instead (as skeptical psychologist Joseph Jastrow described such happenstances in 1900) “just what the normal distribution of such phenomena would lead us to expect”?1 People often find it difficult to view such subjectively jarring experiences from a statistical perspective, even when analysis of the odds is in fact possible. (Sometimes it isn’t.) As Jastrow observed,

TAGS: Anna Maltese, chance, coincidence, Daniel Loxton, The Amazing Meeting, The Odds Must Be Crazy, Theodore RooseveltIt would be pleasant to believe that the application of the doctrine of chances to problems of this character is quite generally recognized; but this recognition is so often accompanied by the feeling that the law very clearly applies to all cases but the one that happens to be under discussion, that I fear the belief is unwarranted.2

What the Heck is a Biostratigrapher?

Jason Loxton during a 2010 research trip to study graptolites in China.

What is “biostratigraphy,” and what on Earth does it have to do with sharks…or with pancakes?

Listen to biostratigrapher Jason Loxton (my brother, and a Junior Skeptic contributor) answer these questions in a quick and breezy CBC radio interview (alternate link). Broadcast on Monday June 22, the interview summarizes Jason’s talk for the “Children’s University” public outreach event, titled “Sharks, Fossils and Meteors: How Geologists Gave the Earth a Birthday.” This free-to-the-public lecture for kids took place yesterday (June 23).

A lab instructor at Cape Breton University and Ph.D. candidate at Dalhousie University, Jason studies the taxonomy and distribution of Ordovician/Silurian graptolites—or “really boring-looking smudges,” he says, cheerfully. This eye-straining endeavor may be “unglamorous and decidedly not ‘trendy,'” as he describes it, but it is just the type of ongoing fossil detective work which has allowed generations of geologists to painstakingly piece together the history of our planet. This project, biostratigraphy, “uses fossils to divide the rock record into relative units of time.” And for that, modest fossils like Jason’s smudges are just the thing.

TAGS: biostratigraphy, evolution, fossils, geology, graptolites, Jason LoxtonThe American Medical Association and the Fight Against Quackery

A detail from the cover of the second edition of Nostrums and Quackery (1912), from the American Medical Association. Browse the first edition online at Archive.org.

“The American Medical Association is finally taking a stand on quacks like Dr. Oz,” announced a post yesterday by Julia Belluz. A health writer at Vox, Belluz has emerged as a sharp critic of popular medical talk show personality Dr. Mehmet Oz with posts such as this, this, and this. (I recommend her thoughtful reflection on the ethics, challenges, and public health concerns of countering medical misinformers, titled “How should journalists cover quacks like Dr. Oz or the Food Babe?” Generations of skeptical critics of quackery have asked those same troubling questions.)

Belluz cites an activist medical student named Benjamin Mazer, who reports on the outcome of a policy proposal recently brought before the American Medical Association’s (AMA) House of Delegates:

TAGS: alternative medicine, American Medical Association, Dr. Mehmet Oz, media, medicine, pseudomedicine, quackeryThe delegates, who represent doctors throughout the country, voted to support the policy proposal as we wrote it. The AMA will now be taking the lead in crafting ethical and professional guidelines for physicians who wish to disseminate medical information in the media. The AMA will also write a report describing how physicians may be subject to discipline for violating medical ethics in the media. And finally, the AMA will be releasing a public statement reiterating our professional values and condemning doctors who use the media unethically. … Many of the leading experts in medical ethics are a part of the AMA. They will now go to work clarifying the nuances of “mass medicine” and will provide recommendations. No longer will quacks be able to benefit from a lack of specific standards and professional codes.

Seeing Mermaids

“The Vision of Columbus” after de Bry, as it appeared in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine No. 389, October 1882. (Daniel Loxton’s collection.)

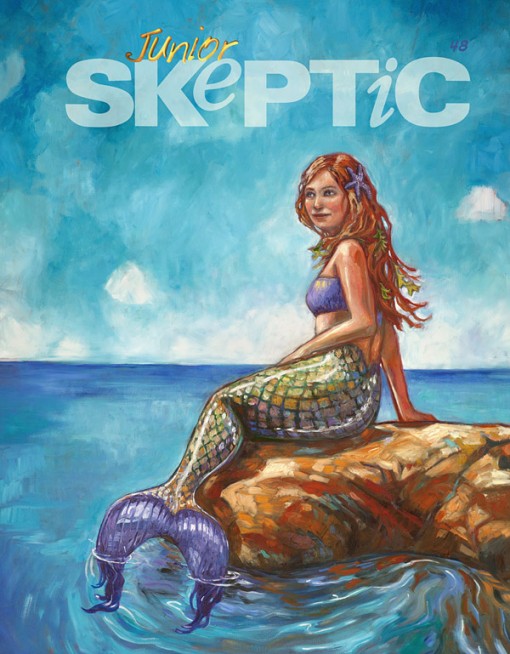

Mermaids—the topic of my Junior Skeptic 48 story bound inside Skeptic Vol. 18, No. 3—are usually considered fantastical, purely imaginary creatures. (Or, at least, they were until Animal Planet and the Discovery Channel aired their infamous 2012 and 2013 documentary-style hoaxes Mermaids: The Body Found and Mermaids: The New Evidence. These hoaxes are discussed in detail in the same issue of Junior Skeptic, in a section excerpted here at INSIGHT.)

In a culture that accepts all manner of supernatural wonders, potions, and wizardry, mermaids have enjoyed a special place in the rhetoric of both organized and folk skepticism. Along with unicorns and leprechauns, mermaids have frequently served as a go-to example of a self-evidently silly claim. When science reporter John Noble Wilford1 accompanied a monster-hunting group to Loch Ness in 1976 for a series of New York Times articles, for example, skeptic Philip J. Klass2 used mermaids to poke fun at the whole enterprise. Klass wrote to the paper in his (pretend) role as “Director Pro-Tem” of the (non-existent) “Mermaid Investigation Sightings Society”:

TAGS: cryptozoology, manatees, mermaids, sireniansA Look Back at Discovery’s Mermaids Hoaxes

This look back at Discovery’s 2012 and 2013 mermaids hoaxes is an excerpt from Junior Skeptic 48 (published in 2013 inside Skeptic magazine Vol. 18, No. 3). The damage done to English-language television’s premier nonfiction brand by these and subsequent misleading ratings stunts (including what I described as “the profound awfulness” of 2014’s Russian Yeti: The Killer Lives) has been widely discussed by critics. As I reflected last year, “At this point, Discovery could announce that they’d made a sandwich during Monster Week and I’d wonder if that were true.”

As the network attempts to regain its dignity, this seemed an opportune moment to review how they put themselves in this compromised position.

Junior Skeptic is written for (older) children and does not include endnotes, though I often call out important sources in sidebars or the text of the story itself. However, I’ve included some links and relevant citations here for your interest.

Junior Skeptic 48 cover. Painting by Corinne Garlick. Oil on board.

Monster hunters have remained interested in mermaid-like creatures such as the Ri [a cryptozoological mystery from Papua New Guinea—see Junior Skeptic 48], and mermaid sightings are still sometimes reported in countries in Africa and elsewhere around the world. But people in the United States and other industrialized countries generally think of mermaids as completely imaginary fantasy creatures like dragons, gremlins, or leprechauns.

Or at least, they did. Then, in 2012, the Animal Planet television channel aired a documentary-style program called Mermaids: The Body Found. [Watch trailer.] Three and a half million viewers watched in astonishment as people identified as U.S. government scientists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) looked straight into the camera and told the public about incredible evidence for the existence of mermaids. Not only are mermaids real, claimed the program, but they are an evolutionary offshoot of the human family tree!

TAGS: cryptozoology, hoaxes, mermaids, mermaids the body found, mythologyAlternative Medicine Critic Wallace Sampson Has Passed Away at Age 85

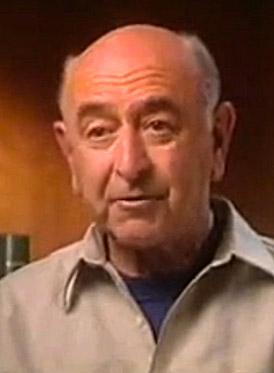

Dr. Wallace Sampson speaking about acupuncture in a television interview. Watch video below.

I’m sad to note the recent passing of a longtime leading critic of alternative medicine, Dr. Wallace Ira Sampson (March 29, 1930–May 25, 2015). Our colleagues at the Skeptical Inquirer reported the news on their Facebook Page on Wednesday, saying, “We were deeply saddened to learn of the death of our friend and CSI Fellow, Wallace (Wally) Sampson, earlier this week.” An obituary has since been published by the San Jose Mercury News. It reports that Dr. Sampson “passed away peacefully on May 25, 2015 at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center”—the very hospital at which he served as Director of Oncology from 1991 to 1997.

Dr. Sampson was a key player in the anti-quackery activist movement which predated, grew up alongside, and (beginning in the mid-1970s) combined to a significant extent with the movement for organized scientific skepticism. (For some details of the California Council Against Health Fraud and other early quack-busting groups, see this short history.) He was the founding Editor of the peer-reviewed journal Scientific Review of Alternative Medicine, a Founding Fellow and board member (emeritus) of Institute for Science in Medicine, a blogger and editor emeritus at Science-Based Medicine, and a founding member of the Bay Area Skeptics. Many of his articles and interviews are available here in a collection of links compiled by the Institute for Science in Medicine.

TAGS: alternative medicine, obituary, quackery, skeptical history, Wallace SampsonHistory and Hyman’s Maxim (Part One)

Ray Hyman demonstrates “psychic” spoon bending in 2012. (Image by Susan Gerbic [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons.)

In a post last year called “The Forgetfulness of Skepticism,” I discussed one of the difficulties that skeptics face as a result of our small community and very broad subject area:

Generations of skeptics have devoted themselves to understanding paranormal and pseudoscientific claims, beliefs, and impostures. But even with those efforts, the fringe has remained radically under-examinded. Because this realm is so vast while the scholars and activists interested in exploring it are so few, our work has often had something of a scrambling quality. In our rush, skeptics have tended to neglect, or at least to set aside for some future time, some of the improvements of better-established fields.

Many other fields benefit from the attention of historical, theoretical, and philosophical spin-off disciplines. Consider, for example, art history, English literature, medical ethics, or philosophy of science. Skeptics, by contrast, are caught in a kind of perpetual startup culture. With so many urgent triage priorities, the considerable task of recording, maintaining, and passing down legacy knowledge becomes a “nice to have”—a luxury for further down the road. As a result, we tend not to remember very well.

TAGS: miracles, paranormal investigation, Ray Hyman, skeptical historyCarl Sagan and the Dangers of Skepticism

This is an excerpt from Junior Skeptic 50 (published in 2014 inside Skeptic magazine Vol. 19, No. 1), which is a ten-page biography of Sagan emphasizing his work in scientific skepticism. A different short excerpt of another section of this story appeared previously in Skepticblog.

Junior Skeptic is written for (older) children, and does not include endnotes, though I often call out important sources in sidebars or the text of the story itself. However, I’ve included some relevant citations here for your interest:

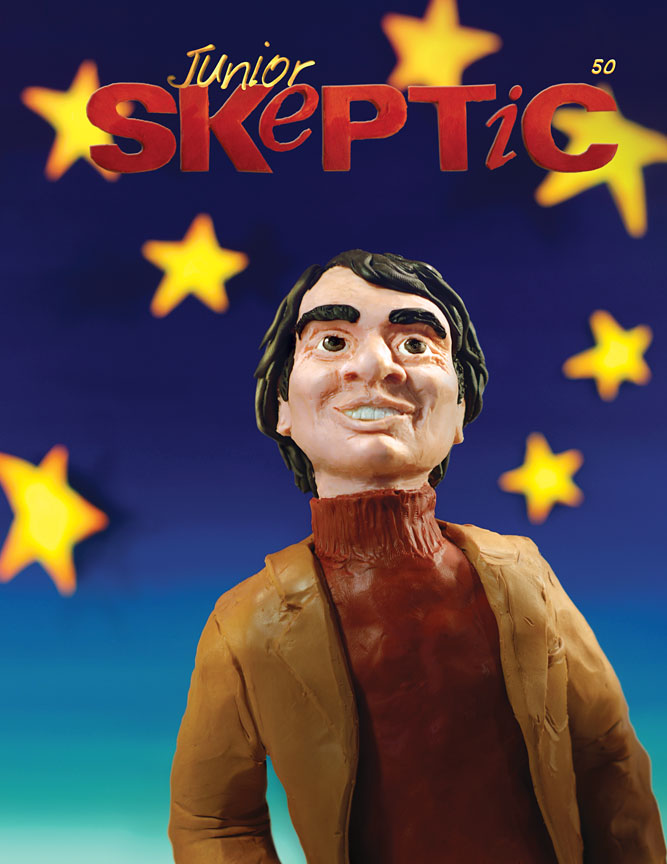

Cover of Junior Skeptic 50, inside Skeptic magazine Vol. 19, No. 1. (Illustration by Daniel Loxton.)

Carl Sagan cared a lot about kooky, far out, pseudoscientific topics. He knew this was quite unusual. He introduced a book section on these fringe science topics by saying, “The attention given to borderline science may seem curious to some readers. … The usual practice of scientists is to ignore them, hoping they will go away.”1 He wished other scientists would care more, and that they were more willing to share their criticisms in public:

TAGS: Carl Sagan, history of skepticism, Junior Skeptic, skepticismI believe that scientists should spend more time in discussing these issues…. There are many cases where the belief system is so absurd that scientists dismiss it instantly but never commit their arguments to print. I believe this is a mistake.2