The following is Daniel Loxton’s review of The Making of Bigfoot: The Inside Story by Greg Long (Prometheus Books, 2004, ISBN 1591021391). Daniel Loxton is Editor of Junior Skeptic magazine. He writes and illustrates most of the Junior Skeptic issues. He has also authored a number of articles and reviews for Skeptic magazine. He lives in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada.

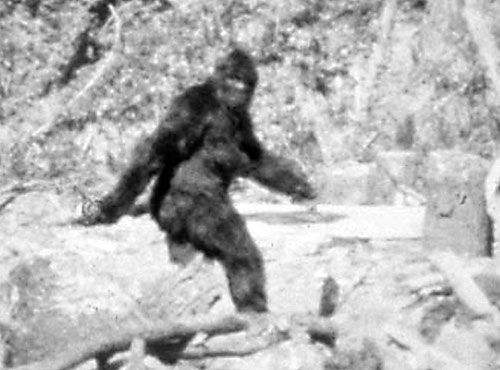

Patterson’s Bigfoot photo … or is it just a guy in an ape suit?

Bigfoot, Big Con

a book review by Daniel Loxton

When Greg Long’s 2004 book The Making of Bigfoot arrived on my desk, I knew it was from Prometheus Books (which is a pretty good start), and about Bigfoot, but nothing else. Having heard none of the buzz about it, I was merely hoping it would prove to be a decent resource for one of my own articles on the subject. Then, when I realized that the entire 476-page book was exclusively about the late Roger Patterson’s infamous 1967 “Bigfoot” film, my heart sank. 476 pages on that tired old chestnut?

Like most skeptics, I’m more than a little sick of the Patterson Bigfoot film. In our hearts, skeptics know three things about the film: that it easily could have been faked, that it almost certainly was, and that it’s very unlikely (despite the periodic rumors) to ever be proven a fake. It certainly looks like a guy in a gorilla suit, but … the film quality is too poor to reach any definitive conclusions. The small size of the creature relative to the grainy film texture prevents any examination of details. (For example, one most definitely cannot see a zipper, as some have claimed!). Supporters of the film, on the other hand, have always insisted either that it could not have been faked in principle, or that Patterson himself could not have done so. Staring at grainy enlargements, the two sides have remained at that impasse for almost four decades.

In the face of this deadlock, Greg Long’s project turned out to be far more interesting than I had anticipated. He largely ignores the old footage and simply asks, Who was Patterson, anyway? Amazingly little seemed to be known about the man behind the most important and controversial “real Bigfoot” footage ever captured. To find answers, Long spent several years traveling the Northwest, tracking down old witnesses, and taping interviews with anyone who was even vaguely connected to Patterson or the film. Each of these contacts often recommended additional sources, whom Long patiently tracked down and interviewed.

What emerged from this exhaustive process turns out to be a fascinating investigative journey—and a page-turner. Engagingly written in the first person, the book reveals a Patterson that is, well, really something.

Grumpier skeptics will find this book completely delicious. It is the story, in the words of one key witness, of “a cheat, a liar, and a thief.” Patterson was many things: an artist, woodworker, acrobat, rodeo-rider, filmmaker, author, and, above all, a con man. Long’s portrait is that of a small-time, back roads scam artist with dreams of the big score.

Ironically, one of the book’s few weaknesses is also a great asset: it’s somewhat repetitive, as witness after witness tells us the same story of getting ripped off by Patterson. Every interview broadly corroborates the testimony of the others. The details are constantly fascinating, frequently hilarious, and sometimes heartbreaking. Patterson seems to have scammed everyone he met, from his best friends to (perhaps) his own mother. One witness relates that Patterson, usually without a phone himself due to unpaid bills, once asked to borrow his phone. He then secretly ran up a long distance bill (in 1960s money!) of seven hundred dollars, which he flatly refused to pay. Although this dupe prefers to remain anonymous, other witnesses tell nearly identical stories.

Apparently, Patterson cheated everybody. He may have run a regular check fraud routine, but his standard approach was simply to run up huge bills and then refuse to pay. He stiffed everyone from Safeway to the hospitals that treated him for cancer. And yet, he constantly got away with it. People were sometimes afraid to collect, for Patterson, although small, was a life-long weightlifter with a reputation for having a violent temper. (According to one witness, he once responded to shouted insults by leaping into a car filled with four loggers and beating two of the men unconscious.) Others felt sorry for him, allowing him to fleece them repeatedly for the sake of his wife and kids. Besides, he seems to have made a point of almost never actually owning anything, so that no one, from courts to friends to collection agencies, could find anything on which to collect.

The Making of Bigfoot is a good read and well worth picking up just to glean the details of how the famous film was shot using a camera and film that were—of course—never paid for. Patterson, in fact, was promptly arrested for grand larceny for stealing the very camera he used at Bluff Creek!

Readers will also discover that Patterson was obsessed with Bigfoot long before he “happened” to catch one on film. Indeed, prior to his fortunate encounter, he authored North America’s very first full book on the subject (the publication of which was itself a saga of apparent crookedness and irresponsibility). He formed companies to pursue Bigfoot ventures, and staged earlier low budget Bigfoot films. Believers have always considered the Bluff Creek footage a happy accident, but Patterson clearly spent years preparing for it.

Both skeptics and believers will be a little unsatisfied with the questions remaining at the end of the day. We know far, far more now than we did when Long began working, but, after three decades, there were bound to be missing or contradictory details. The necessity of relying on eyewitness testimony compounds this problem. (Among the key questions: if Patterson’s footage featured a man in a suit, as his witnesses claim, what happened to it? If we can’t find it, can we ever prove that it actually existed?)

The Making of Bigfoot also functions incidentally as a stinging indictment of the professional Bigfoot hunters (many of whom are interviewed here as well), on whom it places blame for lost opportunities to discover key evidence. In return, cryptozoologists have expressed serious concerns about—or outright ridicule of—Long’s book.

Some of the unanswered questions are likely to remain that way because, as Long concludes, “The Old Bigfooters hadn’t done their job. They failed to nail down the essential facts in the first few days after Patterson returned to Yakima from Bluff Creek.” For example, no one attempted to discover when the film was actually shot, or with what camera, or where it was processed. Several contradictory accounts of the film’s provenance emerged at the time, and no one seems to have dug very deeply into any of it. Early sasquatch researcher Rene Dahinden agreed, telling Long, “There are real dumb t’ings I should have done. The problem is that ve didn’t do our job.” (Long’s phonetic transcription.) Interestingly, Dahinden eventually acquired most or all of the rights to the famous film, which he held until his death. For its part, the modern cryptozoological community has been swift to criticize Long’s book. The Internet is humming with chatter about and condemnation for this exposé of one of cryptozoology’s crown jewels.

The major counterclaim is that Long fell victim to one or more hoaxes when interviewing witnesses. Particular ire is reserved for the two most damaging witnesses: the man who claims to have built Patterson’s Bigfoot suit (costume designer Phillip Morris), and “the Man in the Suit,” as he has been called (a high school friend of Patterson, Bob Heironimus). Unfortunately, these two witnesses disagree on key details regarding the suit—something Long spends far too little time examining. Furthermore, after 37 years, there is no known physical evidence to back up the claims of either man.

I met with John Kirk, author and President of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club, and asked for his impressions. According to Kirk, the “trouble is that Bob Heironimus isn’t telling the truth in any way, shape, or form here.” Like many cryptozoologists, he believes that Heironimus is himself perpetrating a hoax. Kirk claims that his organization discovered the identity of Heironimus (then an anonymous source claiming to have worn a suit in the film) back in 1999. He also alleges that their investigation into his background uncovered “a woman who was present when Heironimus and two other individuals concocted this scheme [to falsely claim Heironimus wore the suit] in her living room … so we were aware five years ago that this was a hoax, and we do not know how it was allowed to grow to this level.” Leaving aside this woman’s specific allegation, Kirk’s primary gripe with the book is shared by many cryptozoologists: Heironimus claims that he wore a horsehide suit built by Patterson himself, which he describes in modest detail, while Morris claims that Patterson bought and used one of his commercial gorilla suits—which he describes in precise detail. Surely, say critics, one or both of these claims must therefore be false. Since neither is clearly supported or debunked by the available evidence, both must be suspect.

After reading the testimony of both, readers may find that they, like me, are inclined to believe that both witnesses are sincere. They may both also be largely correct. If Heironimus did in fact wear the suit (and this appears seductively likely), it is not clear how he would have known how it was made. At the time, only one commercial gorilla suit (Morris’ high-end show biz costume) was on the market in North America, and Heironimus would probably never before have seen one in person. Also, Patterson was in the habit of claiming other people’s work as his own (indeed, he told researchers that he invented the plastic clip used to seal bread bags), and both Morris and Heironimus agree that Patterson created the suit’s mask (something also suggested by other witnesses’ testimony). Moreover, many of the details Heironimus supplies, such as an unpleasant smell and a weight of around 20 pounds, are quite consistent with the latex and dynel suit Morris was selling at that time. Even had Heironimus once known how the suit was built, it seems reasonable to suspect that after 37 years his recollection of the suit’s materials could easily be faulty. Either of these circumstances (initial misunderstanding or later memory failure by Heironimus) would sync the two witnesses testimony. Since either is entirely plausible, it seems appropriate to allow both as possibilities. (Neither hypothesis, of course, would be easy to confirm.)

The Making of Bigfoot is destined to make waves for some time to come. Its examination of Patterson’s character throws a dark shadow over the whole affair, and stands as an embarrassing challenge to supporters of Patterson’s film. Although all commentators agree that the sasquatch legend does not stand or fall on this footage alone, it has been too important for too long to be surrendered easily. In the absence of physical corroboration (i.e., the suit), the most dramatic testimonies in Long’s book will remain contentious—as they should.

Skeptics should beware that these are deep waters. Neither the film itself nor the surrounding testimony has ever offered very much hard evidence for any interpretation. Further, poorly substantiated claims and counterclaims have been coming and going for decades without any final explanation emerging. It is one subject on which skeptics have apparently been wrong before. John Kirk points out that, “There have been too many other people who’ve come along to say they were the guy in the suit. This, I believe, is number four: three [are] self-claimed, and one mistakenly—or perhaps deliberately—ID-ed as the man in the suit when he jolly well wasn’t.”

Nonetheless, Kirk offhandedly concedes, “Patterson, y’know, he’s no angel. There’s no question about that … This guy was a slapdash kinda guy that you really shouldn’t do business with.” Readers of Long’s book will agree. “Roger Patterson’s character fails the smell test,” writes Long. “Sum up all the information about Roger Patterson, and it comes down to two simple points. One, he had the ability to conceive of and create a Bigfoot suit, and two, he was a crook.”

To these, skeptics might add a third: tangled as this business may be, the creature in the film still looks an awful lot like a guy in an ape suit.

Judge Sends Evolution Lawsuit to Trial

Tuesday, April 6th, 2004

Atlanta, Georgia (AP) — A federal judge refused to dismiss a lawsuit against a school district’s practice of posting disclaimers inside science textbooks saying evolution is “a theory, not a fact.”

The Cobb County schools’ disclaimer, in the form of a sticker on the inside front cover of textbooks, could have the effect of advancing or inhibiting religion, U.S. District Judge Clarence Cooper ruled in ordering the suit to go to trial.

“We’re very excited about this,” said attorney Michael Manely, who represents the six Cobb County parents who sued the system in August 2002.

The lawsuit argues that the disclaimer restricts the teaching of evolution, promotes and requires the teaching of creationism and discriminates against particular religions.

The sticker reads:

This textbook contains material on evolution. Evolution is a theory, not a fact, regarding the origin of living things. This material should be approached with an open mind, studied carefully and critically considered.

The judge weighed the constitutionality of the issue by applying a three-pronged test handed down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1971. In order to get the lawsuit dismissed, the school board had to show that the disclaimer was adopted with a secular purpose; that its primary effect neither advances nor inhibits religion; and that it does not result in an excessive entanglement of government with religion. In his order signed last Wednesday, Cooper said the school board satisfied him on the first issue.

But he noted that while the disclaimer has no biblical reference, it encourages students to consider alternatives other than evolution. The judge found that the disclaimer could have the effect of advancing or inhibiting religion. “Indeed, most of the board members concurred that they wanted students to consider other alternatives,” Cooper wrote.

The theory of evolution, accepted by most scientists, says evidence shows current species of life evolved over time from earlier forms and that natural selection determines which species survive. Creationism credits the origin of species to God.

In 1987, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled creationism was a religious belief that could not be taught in public schools along with evolution.