Humanist Perspectives interior spread featuring interview with Michael Shermer (photo by David Patton).

Humanist Perspectives covers: issue 154 featuring Christopher diCarlo on the theme of Darwin & the Evangelicals; issue 150 featuring Junior Skeptic Editor Daniel Loxton on Education & Critical Thinking; issue 160 featuring Shauna Tierney on The War on Science & Reason.

Humanist Perspectives

interviews Michael Shermer

The current issue of Humanist Perspectives features an interview with Michael Shermer about “The War on Science & Reason,” the Bush administration, censorship, postmodernism, and optimism for the future.

DOWNLOAD a FREE sample of the magazine,

which includes the full interview with Shermer (2.6MB PDF) >

Michael Shermer Recounts

Alien Abduction Experience on Film

Michael Shermer in Race Across America, 1983 (video still).

Most of you know the story already, which I’ve recounted in Why People Believe Weird Things, in one of my Scientific American columns (download the PDF), and in countless lectures and television shows on UFOs and alien abductions. Since no one ever produces video evidence of an abduction experience, I thought it would be fun to share with you my video proof that I was abducted by aliens.

The context: the 1983 Race Across America, the 3000-mile nonstop transcontinental bicycle race from L.A. to Atlantic City. I was being filmed by ABC’s Wide World of Sports as I crossed the Mississippi River, with the Olympic speedskating gold-medalist Eric Heiden interviewing me. It was to Eric that I recounted my experience of what happened earlier that day, after riding 1280+ miles nonstop and going over 80 hours without sleep …

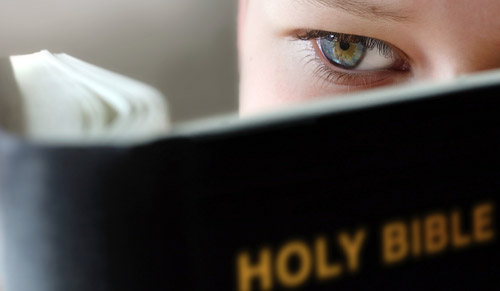

In this week’s feature article Rayyan Al-Shawaf reviews god is not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything, by Christopher Hitchens. (Warner Twelve, 2007, ISBN 9780446579803). Rayyan Al-Shawaf is a writer in Beirut, Lebanon.

Hitchens and God

a book review by Rayyan Al-Shawaf

This is not some bilious tirade, but a cogently argued — if polemical — indictment of religion by one of the West’s most outspoken defenders of rational thought and free inquiry. Long known for his flippant attitude toward the “holy” — both before and after his major shift from the extreme left to the center-right — Christopher Hitchens has finally constructed a systematic argument against the entire totalitarian enterprise of religion. According to Hitchens “There [are] four irreducible objections to religious faith: that it wholly misrepresents the origins of man and the cosmos, that because of this original error it manages to combine the maximum of servility with the maximum of solipsism, that it is both the result and the cause of dangerous sexual repression, and that it is ultimately grounded on wish-thinking.”

Perhaps inevitably, Hitchens suggests, such belief-systems lead to the institutionalization of totalitarianism. “Religion even at its meekest has to admit that what it is proposing is a ‘total’ solution, in which faith must be to some extent blind, and in which all aspects of the private and public life must be submitted to a permanent higher supervision.” In between his frank digs at “the crimes and horrors of the Old Testament,” “the foolish myths of the New,” and the “rather obvious and ill-arranged set of plagiarisms” that is Islam, Hitchens attempts to construct a one-size-fits-all argument against religion.

On this score, the author is arguably at his most persuasive when demonstrating that, in addition to lacking scientific evidence, God’s existence is virtually irrelevant to the grand cosmic design. “No divine plan, let alone angelic intervention, is required. Everything works without that assumption.” And Hitchens does not stop with Ockham’s razor — by which we determine that the simplest explanation is the most likely — but throws in a few other philosophers’ findings as well. Indeed, he makes reference to Karl Popper’s criterion of empirical falsifiability — in order for a proposition to be scientific there must exist a mechanism by which it could be refuted — when discussing the absurdity of religion posing as science.

Given that God is not needed for us to make sense of most of the natural phenomena around us, and bearing in mind that the argument for God’s existence admits of no means by which it could be falsified, religion begins to seem like an anachronism. The age when “God’s doing” was the catch-all explanation for everything inexplicable has passed, if not simply because we are increasingly able to explain our world and beyond without recourse to non-scientific interventionist factors. In this regard, the author pointedly asserts that “[r]eligion comes from the period of human prehistory where nobody … had the smallest idea what was going on.” For this reason alone, “the final ripping of the whole disguise is overdue.”

It will doubtless come as a frightful shock, but even Christopher Hitchens can be politically correct. The trick to political correctness, irrespective of whether you are a believer or an atheist, is to consider religions morally equal, so that all are equally good … or equally bad. Notwithstanding the title of chapter eight (“The ‘New’ Testament Exceeds the Evil of the ‘Old’ One”), Hitchens seems to consider all religions — even those he does not discuss — as equally poisonous.

This can be problematic. Without forgetting Christianity’s history of barbarism, and the fact that the sadistic concept of eternal hellfire was introduced by the New Testament, is it not significant that the latter’s God prescribes a good deal less violence for this life than His counterparts in the Old Testament and the Quran? Are the teachings of figures like the Buddha and Jesus, stern and ascetic as they may be, comparable to the explicit incitement to violence so often voiced by Muhammad and the Old Testament prophets?

With the exception of Judaism and Christianity, Hitchens’s often witheringly funny barbs are directed at historical instances of religious barbarity or stupidity (often both), and not at the doctrinal source-material, with which the author does not fully engage. This is especially true of Hitchens’s (brief) discussion of Islam, and passing references to historical injustices committed by Hindus, Buddhists, and Shintos. Given the ambitious scope of his project, Hitchens’s argument is more a general exercise in reason and logic — buttressed by a series of witty asides — than an in-depth dissection of this or that specific religion.

Still, one fell swoop is sometimes all it takes to lay bare the depravity of several religions. Consider the terrifying tale of Abraham and his son Isaac, common to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. “Perhaps afflicted by a poor conscience, but at any rate believing himself commanded by god, Abraham agreed to murder his son.” This is one of many examples of the immorality of the God absurdly revered as unfailingly moral by all three religions. Though in this instance — unlike so many others — God magnanimously decides against the shedding of blood, he reveals his desire for total control over the human. Meanwhile, Abraham comes off as the kind of father whose children should promptly be trundled off to foster care. Hitchens powerfully remarks that “ethics and morality are quite independent of faith, and cannot be derived from it.”

a calvary at Sicily, Italy

There is also an insightful discussion of the Vatican’s belated decision to absolve Jews of responsibility for “deicide.” The ramifications of renouncing belief in the sinister twin-notions of collective and inherited guilt are most significant. Commenting on the crucifixion of Jesus, Hitchens observes: “If you once admit that the descendants of Jews are not implicated, it becomes very hard to argue that anyone else not there present is implicated, either.” In other words, how can humans today be considered responsible for the crucifixion of Jesus, as required by Christianity? And why should those who understandably refuse to accept responsibility for something in which they had no hand find themselves consigned to eternal hellfire?

Hitchens’s dismissal of secular totalitarianism as a variation of religion is only partially successful — a deeper reckoning with secular evil is needed — while his attempt to argue that the moral among the devout are not truly religious strikes one as rather facile. He also makes a few mistakes, especially when tackling Islamic subjects. For example, it is the Hadith (not the Quran) which prescribes death for apostates.

Fortunately, however, Hitchens’s discussion of Islam does offer an understanding of the larger issues at stake. He highlights the salient fact that “[o]nly in Islam has there been no reformation,” and observes that prospects for such a phenomenon are hardly encouraging. Seizing upon the “empty-headed multiculturalism” of the West, which may well lead to “cultural suicide,” Hitchens laments the widespread coddling of Islam: “[A]t the very point when Islam ought to be joining its predecessors in subjecting itself to rereadings, there is a ‘soft’ consensus among almost all the religious that, because of the supposed duty of respect that we owe the faithful, this is the very time to allow Islam to assert its claims at their own face value.” Nothing but a drastic shift in priorities can salvage this sorry state-of-affairs. Indeed, given “our new semi-secular and mediocre condition,” the author poignantly concludes that “we are in need of a renewed Enlightenment.”

When all is said and done, Christopher Hitchens, who thanks a number of similarly minded friends (including Michael Shermer, editor of this magazine) for inspiring him, has made a serious contribution to his profession. If the intellectual’s task is to seek the truth, this already difficult mission has long been exacerbated by the widespread popular acceptance of the unscientific and ahistorical “meta-narratives” (in Jean-François Lyotard’s words) peddled by totalitarian ideologies like religion. Over the centuries, many such “meta-narratives” or “unified field theories” (Hitchens’s term) have been mistaken for truth. Consequently, intellectuals have found themselves obliged to spend much of their time debunking myths and disproving lies — a major and quite unnecessary distraction — in order to better clear a path for the unhindered pursuit of truth.

In fact, the spectacular success of ideology, religious or secular, has been such that an intellectual’s life work almost necessarily becomes an exercise in demolition. While the (often demented) ideologue will construct a giant, many-mansioned edifice on the shakiest of foundations, the intellectual has the unenviable task of showing up the next day, chisel in hand, in order to chip away — bit by bit — at the house of lies. Indeed, the intellectual is often compelled by circumstance to become an iconoclast. This was the situation when Socrates — whom Hitchens so admires — was around, and remains true today. In knocking off a sizeable chunk of that massive wall of deception, god is not Great serves a noble purpose, and brings us ever closer to a still far-off time when intellectuals the world over can finally dedicate themselves fully to the pursuit of truth.

Philly Bans Psychics

According to an article on MSNBC recently, Philadelphia psychics, “never saw it coming. City inspectors shut down more than a dozen psychics, astrologers and tarot-card readers after learning about a decades-old state law that bans fortune telling for profit.”