We’d like your feedback on eSkeptic

We’re interested in finding out what you think about eSkeptic, so we can continue improving it! Please take a few minutes to answer our questionnaire.

Update

Thank you to everyone who completed our survey. We appreciate your feedback very much. The survey is now closed to responses.

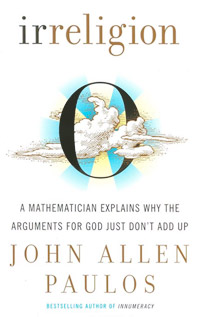

In this week’s eSkeptic, Norman Levitt reviews John Alan Paulos’ book entitled Irreligion: A Mathematician Explains Why the Arguments for God Just Don’t Add Up (Hill and Wang, 2007, ISBN 0809059193).

Gimme that Old-Time Irreligion

a book review by Norman Levitt

The very first thing I did in drafting this review was to Google Chester Alan Arthur. I trust my readers will recall the name, if only after a bit of head-scratching, as that of one of the most obscure and unmemorable of American presidents, a run-of-the-mill New York politician who attained to the highest office in the land by virtue of the assassination of his almost equally obscure predecessor, James A. Garfield, who picked the party wheel-horse Arthur as his running mate for reasons now totally forgotten.

What has this to do with John A. Paulos’s recent book Irreligion? It is well known, of course, that some our most eminent presidents—Jefferson, Lincoln, Madison—spurned orthodoxy in religious matters, even to the point of—to use Paulos’s convenient title—irreligion. This, of course, is sufficiently embarrassing to our fundamentalist ayatollahs that they have been furiously rewriting history, chiseling away at the facts with all the fury of the restored priests of Amun hacking off Nefertiti’s heretical nose. What interested me more, however, was the question of whether disdain for religion was purely the province of politicians who where gifted intellectuals as well, or whether it was at one point so widespread and socially acceptable that even routine mediocrities, hacks, and tub-thumpers could espouse such views without being banished from public life and high office.

So I picked me a president—the most unmemorable I could find (Millard Fillmore is too memorable for being unmemorable)—and took a peek at what is known or surmised about his religious convictions. Chester Alan Arthur fit the bill admirably. According to The Religious Views of our Presidents, by Franklin Steiner, Arthur finds his place in the list under the heading “Presidents whose religious views were doubtful.”

In the 19th century, at least, political viability of an aspiring public figure was not unconditionally dependent on a show of religious enthusiasm. That is not to say that affected reverence for faith (as well as open hostility to the “wrong” faith) were absent from the political stump. Then, as now, candidates and office holders often made a big show of their ostensible piety. But they did so in a society where it was more or less understood and expected that a broad spectrum of attitudes toward religion, as such, existed, that “freethinkers” and “infidels” were part of that spectrum, and that the “village atheist” was a standard, and even admirable element of the intellectual scene. The celebrity of such writers as Mark Twain (a doubter) and Ambrose Bierce (an atheist outright) attests to this. The phenomenon of the atheist celebrity continued even into the first part of the 20th century, most notably in the person of America’s great curmudgeon, H.L Mencken.

Somehow that tradition died away by stages in the Cold War era, so much so that by the turn of the new century the Bush administration brought religion back into the White House, and in the run up to the 2008 presidential election, a loony fundamentalist preacher like Mike Huckabee was taken seriously as a presidential candidate, while the others in both parties fell into line, sincerely or otherwise, to demonstrate that their own piety was at least minimally acceptable. In particular, the presumptive Republican standard bearer John McCain, having indiscreetly uttered some home truths about the religious right in the past, had to crawl and snivel (flip-flopping extravagantly) in order to make his peace with that odious crowd before he could seize the party’s crown.

Paulos’s Irreligion

Given this religious revival, it is of more than passing interest to note the recrudescence of blatant and aggressive atheism in the past couple of years. All of a sudden, the lonely or isolated non-believer can find a veritable library of god-debunking literature to sustain him merely by taking a brief on-line tour of Amazon and the like. Note that this is no longer the cantankerous low-rent pamphleteering of a few lonely cranks or the screeds of minuscule contrarian sects, as might have been the case a decade ago. Rather, these books come from big-time commercial publishers savvy about the likelihood of finding profit in the denunciation of prophets, and from authors of some prior repute, often with heavy-caliber academic credentials. Now, mathematician John Alan Paulos, best known as the author of Innumeracy, has joined the lists with his newest book, Irreligion.

Paulos deserves high praise for turning out a book that is brief, forthright, and amiable. While making the same basic points as, say, Dawkins’s The God Delusion, it avoids the often choleric tone of that work, keeping a light, conversational tone where Dawkins hurls flaming rhetorical fireballs of denunciation. This is not meant as a criticism of Dawkins, whose grim disgust with the cruel absurdities of religion echoes what many of us feel in our hearts. But it does point up the fact that an atheist world-view does not necessarily lead to a foul-tempered misanthropy that is forever giving voice to searing disdain for a species that is so nasty and foolish as to delude itself into religious fervor. Paulos’s cheery offhandedness, which never declines into mere diffidence, clearly makes the point that to be an atheist, one does not need to be a professional malcontent.

The book is organized in a way that readers inclined to skepticism but who have never seriously studied the debate over the viability of theism will find convenient and quite useful in their private debates with friends, relatives, and even clergymen of various persuasions. Paulos lays out, seriatim, most of the classical philosophical arguments for the existence of a deity, and immediately refutes them as they arise. Thus we find the ontological argument, the argument from First Cause, the argument from design, the argument from the seeming existence of moral universals, and so forth, laid out one by one and just as soon demolished. It will be noted that these chapters are as brief as they are easygoing.

Some of Paulos’s critics, noting this brevity, complain that he is too brisk and thoughtless in giving such cavalier treatment to arguments so ancient and weighty, over which so many sages have wracked their brains in ages past. But this misses Paulos’s larger and more important point: The hypothesis that a deity created the universe and somehow still intervenes in it is, on the face of it, an extravagant, inelegant, and superfluous supposition. It lacks any support from our direct experience of the world, nor even from the subtle and indirect inferences of modern science. Therefore, in order to make it plausible, let alone convincing, requires arguments that are clear, direct, and compelling. An enormous burden of proof lies heavy on the proponents of theism; atheism is really the default position. Paulos finds that the classical arguments cited are at best verbally dexterous, and that typically, they head into muddy and confusing ground before they get too far. In large measure, they reduce to arguments from the deployment of pompous but vacuous terminology. Therefore, there is no reason to take them all that seriously, since they flounder early and often, and are riddled with self-contradiction when picked apart by a relentlessly logical mind.

Some lapses can be found in Paulos’s exposition. The newly-fashionable argument from the “irreducible complexity” of biological systems is a mainstay of the crypto-creationist Intelligent Design movement, but Paulos’s treatment of this ploy is, for once, too brief and superficial; he ought to have included some specific and concrete example of the consistency of standard evolutionary theory with claimed instances of irreducible complexity, rather than simply tossing the idea into the same pot as the argument from design in general. Likewise, a bit more might have been said about the supposed “fine tuning” of physical constants, especially in the light of various new hypotheses concerning the foundations of physics. Finally, I note that Paulos digresses into the famous question posed by Eugene Wigner: Why does the vast corpus of mathematical ideas developed without any applications in mind turn out to be so useful in describing what we can discover of physical reality, to the extent that it is virtually impossible to envision a “physics” detached from these mathematical formalisms? This, it seems to me, is a question that bears very remotely, at most, on the arguments pro and con theism, and the book needn’t have considered it at all. Nevertheless, I find that Paulos’s analysis is superficial and a little flaccid, especially in view of the fact that he is a professional mathematician. Wigner’s question remains deep and resists an easy answer.

But these minor points don’t much detract from the overall value of what Paulos has given us. Irreligion will, I’m confident, take a distinguished place in what one might call the canonical literature of the New Atheism, and I highly recommend it, especially to bright youngsters who will find its occasional use of mathematical ideas pleasant rather than repellent.

The New Atheism

An important question remains: Why has atheism and skepticism toward religion suddenly emerged as a question of great current interest, at least among the literate, in the past few years? Clearly something has happened to break atheists of their tendency to nurture their disbelief privately and to keep their opinions to themselves.

It seems obvious that politics has a lot to do with this, specifically the cultivation of the religious right as a phalanx of conservative storm troopers who are rewarded by conservative politicians by having their singular dogmas incorporated, as much as possible, into public policy. The increasing pressure on women’s reproductive rights, the suppression of stem cell research, and, most egregiously, the fresh intrusion of creationism into public schools are primary instances of this. Beyond these concrete horrors, there is no escaping the fact that the miasma of compulsory religiosity has thickened and diffused throughout society. For instance, one notes, rather queasily, the success of the Evangelicals in turning the Air Force Academy into a virtual fundamentalist seminary where cadets from all sorts of backgrounds are relentlessly pressured by officers and upperclassmen into declaring for the Born-Agains.

Atheists, who, despite polls, have never been all that rare, have come to mistrust the notion that they can believe as they will, undisturbed, provided they remain discreet about it. The mood fostered by the religious right seems to tend toward the inquisitorial. Scientists, in particular, representing the one vocation in which non-belief is the norm, rather than the outlier, have sensibly concluded that the culture in which they have quietly lived is being attacked at its foundations. It’s one thing to send your kids to a public school where “under god” is formulaically recited as part of the daily Pledge of Allegiance. It’s quite another to have your kid’s elementary biology class interrupted by harangues against “Darwinism”, or to see the Bible, taught as literal truth, surreptitiously introduced into the curriculum. When matters have come to that pass, scientists, among others, see little point in not fighting back openly. Thus one now sees a torrent of books, largely by scientists and sympathetic philosophers, striking back, not only at the enemies of stem-cell research and the proponents of Intelligent Design Theory, but at the very roots of the cultural tic that provides these miscreants such fertile ground: supernatural religion predicated upon a supreme being.

Then, too, one must consider the possibility that as the ostensible religious uniformity of the nation begins to dissolve, the sort of person who habitually responds to questionnaires about faith by listing himself as “unaffiliated, but a believer” has, at long last become more honest with himself and with the rest of us, frankly acknowledging the deep vein of skepticism underlying his disinclination to become a churchgoer. I suspect that many of the readers of the New Atheists’ books fall into this category, and are more willing to let their doubts see the light of day.

The Return of the Suppressed

The new boldness of atheists and nonbelievers is not so much a novel development as an unconscious return to the mindset of an earlier century. Contrary to the standard myth of progress, America spent many years going backwards in point of publicly-acceptable attitudes toward religion, even as Western Europe eagerly abandoned its historical obedience to Christianity, and turned itself into a society where atheism is pretty much the norm, the persistence of officially-established churches and similar vestigial institutions notwithstanding. I don’t expect America to move that far that fast. Religion still has its claws into too many people and communities; one doubts that the airwaves will soon be full of clear-channel radio stations proclaiming the indispensability of skepticism and the savage wrongheadedness of biblical literalism.

All the same, our supposedly provincial forebears seem to be on the brink of vindication. One of these days, we may well see a major election where a candidate needn’t supply the press with a photo-op of him or herself and family dutifully sitting through an acceptable church service. (Indeed, we may already have witnessed such a miracle in the election of Socialist Bernie Sanders as U.S. Senator from Vermont!) In my search for relevant historical minutia, I discovered that even the much-despised Millard Fillmore ought to be regarded as a secularist hero for our time. It seems that as a New York legislator, Fillmore led the fight to enable citizens unwilling to swear an oath to a Divine Being to give testimony in state courts nonetheless. Politicians with that kind of principle and that kind of guts are still in short supply, certainly on the right. But one might hope that the increasing eagerness of atheists like Paulos to go public with their beliefs will have a positive effect on the yet-unfulfilled struggle to have this country and its social institutions truly respect freedom of opinion.

Don’t Be Such a Scientist!

Over the past several episodes, Skepticality has interviewed some of the notable scientists featured in the new pro-Intelligent Design documentary Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed. This week, the last word on the controversy goes to Dr. Randy Olson, the biologist-turned-filmmaker whose 2006 documentary Flock of Dodos: The Evolution – Intelligent Design Circus examined the communication breakdown between the science community and the rest of the world on the subject of evolution.

Dr. Olson strives to improve the reputation of science in the court of public opinion, where the Religious Right and Intelligent Design movements continue to wedge their way in by “teaching the controversy.” On his Shifting Baselines blog, Dr. Olson was one of the first scientists to express concern that the well-funded Expelled was likely to succeed in selling its message to a tremendous number of people. The “dodos” of the blogosphere responded with incredulity.

At the request of many Skepticality listeners, Swoopy spoke with Dr. Olson about his controversial opinions — and about his new film, Sizzle: A Global Warming Comedy.

Dr. DeBunko: The Short Stories

available free on wowio.com

by Chris Wisnia (www.tabloia.com)

“The coolest, hippest thing to hit skepticism since Lisa Simpson began reading Junior Skeptic magazine (when Homer had his alien abduction experience)” —Michael Shermer

See the debunker of the supernatural matching wits against misinformed, stubborn, uneducated and superstitious folk around the globe! Only he can hope to make the world a safer, more rational place, as he opposes beliefs in corpse-eating werewolves; cattle mutilations; spontaneous combustion; sex-craved succubi, incubi, and the devil himself! Collecting eleven of the master of debunkery’s adventures, including his rare mini-comics!

Dr. Gregory Benford will be speaking on Sunday, May 25, 2008 at 2:00 pm

our next lecture …

Beyond Human:

Living with Robots & Cyborgs

with Dr. Gregory Benford & Dr. Elisabeth Malartre

Sunday, May 25, 2008 at 2:00 pm

Baxter Lecture Hall, Caltech

Concepts once purely fiction — robots, cyborg parts, artificial intelligence — are becoming part of everyday reality. Soon robots will be everywhere, performing surgery, exploring hazardous places, making rescues, fighting fires, and handling heavy goods…

READ MORE about this lecture >

Important ticket information

Tickets are first come first served at the door. Sorry, no advance ticket sales. Seating is limited. $8 Skeptics Society members & Caltech/JPL Community; $10 General Public.