In this week’s eSkeptic:

Lecture at Caltech this Sunday

The Grand Design

with Dr. Leonard Mlodinow

Sunday, December 5, 2010 at 2 pm

Baxter Lecture Hall

WHEN AND HOW DID THE UNIVERSE BEGIN? Why are we here? Why is there something rather than nothing? What is the nature of reality? Why are the laws of nature so finely tuned as to allow for the existence of beings like ourselves? And, finally, is the apparent “grand design” of our universe evidence of a benevolent creator who set things in motion — or does science offer another explanation? In this lecture by Leonard Mlodinow, based on his co-authored book with Stephen Hawking, answers to these ultimate questions are answers based on the most recent scientific evidence. For example, Mlodinow and Hawking show that according to quantum theory, the cosmos does not have just a single existence or history, but rather that every possible history of the universe exists simultaneously. When applied to the universe as a whole, this idea calls into question the very notion of cause and effect. The authors further explain that we ourselves are the product of quantum fluctuations in the very early universe, and show how quantum theory predicts the “multiverse” — the idea that ours is just one of many universes that appeared spontaneously out of nothing, each with different laws of nature. They conclude with a riveting assessment of M-theory, an explanation of the laws governing us and our universe that is currently the only viable candidate for a complete “theory of everything.” If confirmed, they write, it will be the unified theory that Einstein was looking for, and the ultimate triumph of human reason.

Tickets are first come first served at the door. Seating is limited. $8 for Skeptics Society members and the JPL/Caltech community, $10 for nonmembers. Your admission fee is a donation that pays for our lecture expenses.

Skepticality

Inside Consumer Reports

One of the most positive aspects of the skeptical movement is advocacy for consumer awareness about the claims made by producers and advertisers of all sorts of products, from the outlandish to the commonplace.

This week on Skepticality, Swoopy talks with Robert Tiernan, Managing Editor of Consumer Reports magazine, the monthly publication produced by The Consumers Union. For nearly 75 years, the Consumers Union has utilized rigorous scientific testing to separate hype from fact and good products from bad ones — empowering consumers to think more critically about everything from cars to health care.

MonsterTalk

The Iceman Goeth

Late in the 1960s, in the era which gave us the famous Patterson-Gimlin Bigfoot film, fairgoers in Minnesota were confronted with a marvel: a hairy, primitive-looking humanoid frozen in a block of ice. Was it an anthropological relic? Was it a sasquatch?

As investigators from the Smithsonian Institute and cryptozoological researchers studied the frozen creature, they came to very different conclusions as to what it represented. The MonsterTalk hosts interview Bigfoot researcher and former side-show performer Matt Crowley — and try to crack the case of The Minnesota Iceman.

About this week’s feature article

In this critical review of paleontologist Simon Conway Morris’s book Life’s Solution: Inevitable Humans in a Lonely Universe, paleontologist Dr. Donald Prothero deconstructs the myth of progress and evolution. Morris argues that convergent evolution means certain features will inevitably arise in nature such as eyes and ears, limbs and brains, and therefore these solutions become unavoidable and thus predictable. This book review appeared in Skeptic magazine volume 10, number 3 in 2003.

Inevitable Humans?

Or Hidden Agendas?

a book review by Dr. Donald Prothero

The optimist sees a glass and says it’s half full; the pessimist says it’s half empty. So goes the classic metaphor for how our expectations and beliefs can bias our judgment and perception, and cause us to see only what we want to see.

We’re all familiar with examples of how Creationists can take straightforward scientific facts and twist them to fit their peculiar view of the world. Almost as soon as we detect this bias, our baloney alarms go off, and we read their arguments much more skeptically, because we have good reason to doubt that they have used the facts correctly.

But the bias is not just among Creationists. All humans have a tendency to see and emphasize what fits their preconceptions, and ignore what does not. Scientists like to think of themselves as “objective” and not prone to those biases, but as many philosophers of science have pointed out, this is not true. Scientists are all too human, and their perceptions are largely affected by the culture in which they live, as well as how they were trained. No matter how “objective” scientists try to be, they are subject to all sorts of cultural and social expectations that distort their interpretations. Unfortunately, many scientists are unaware of these prejudices or unwilling to recognize that they might be subject to them, but the effects are there just the same. We all have a tendency to seek “facts” that are part of our theoretical universe, whether we are conscious of this or not. Darwin believed that he was objective in accumulating facts in an inductive fashion, but during a moment of candor, he wrote, “How odd it is that anyone should not see that all observation must be for or against some view if it is to be of any service.”

“Innocent, unbiased observation is a myth”

This bias is particularly apparent when scientists (and other people) begin to speculate outside the normal realm of testable hypotheses, and try to answer ultimate questions such as: “Are we alone in the universe?” or “What are the chances of there being another form of intelligent life like us?” These kinds of questions lead to non-scientific speculations about the meaning of our existence, or how humanity’s status in the universe casts light on religious and philosophical questions of that nature. Science-fiction writers have long worked from the premise that some other form of alien life exists out there, looks something like us, and can communicate with us. Such optimism led to the SETI project, and to movies and novels ranging from H.G. Wells’ pessimistic War of the Worlds to Steven Spielberg’s more optimistic view of aliens in Close Encounters of the Third Kind and ET, and a less anthropomorphic view of aliens in Carl Sagan’s Contact. But these kinds of portrayals have always been relegated to science fiction, and are not taken seriously by scientists in the relevant fields.

When trained scientists have speculated on such matters, they tend to be less optimistic. For decades, the scientific literature on the topic has been nearly unanimous that the evolution of humans on this planet was a unique and unlikely event, and that even if alien life existed on other planets, it would have little chance of resembling us. George Gaylord Simpson put the arguments in their clearest form in his 1964 essay “On the nonprevalence of humanoids” (Science, v. 143, pp. 769–775). More recently, Stephen Jay Gould argued in a number of books that chance and contingency are important factors in evolution, and that evolution is not predestined to follow a certain path that, as the anthropocentric bias dictates, eventually leads to us. The history of life could have been played out in a near infinite number of alternate scenarios if one or two events early in the sequence had occurred differently.

Gould made this contingency argument most strongly in his 1989 book Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History (W. W. Norton), which popularized the amazing soft-bodied Cambrian fauna from the Burgess Shale of Canada. Gould argued that with so many bizarre experimental body forms (most of which do not survive today), there was no way of predicting what the future shape of life would be like from this early experimental phase. (The title of the book refers to the famous Frank Capra movie, It’s a Wonderful Life, where Jimmy Stewart gets to view an alternate future predicated on a very slight difference in initial conditions — in this case, that his character had never been born).

Our ancestors include the Burgess Shale fossil known as Pikaia, which was just a tiny wormlike lancelet back then, and a very minor part of the fauna, so that a Cambrian biologist would have no way of guessing that eventually the vertebrate body plan would be a great success, and most of the other types would die out. If the tape of life had been rewound and replayed, perhaps some other group would have dominated, and we would not be sitting here speculating about it!

This argument is neither surprising nor novel to most scientists, and there has been very little disagreement with it in the scientific community — until now. Simon Conway Morris, a respected Cambridge paleontologist and one of the world’s experts on the Burgess Shale fauna, has seen fit to disagree with Gould (and prevailing scientific opinion) wherever possible. His first attempt was his 1998 book The Crucible of Creation: The Burgess Shale and the Rise of Animals (Oxford University Press), his counter to Gould’s Wonderful Life. In this book, he argued that the Burgess Shale fauna isn’t quite as bizarre as earlier accounts (not just those of Gould’s but even in his own writings) suggested. In this latest book, Life’s Solution, he takes issue with Gould again, but sadly Steve is no longer alive to answer him.

Conway Morris is clearly bothered by the materialistic and non-anthropocentric implications of a history of life where chance events are important, and by the idea that humans are just an accidental by-product of chance events, not the likely end-product of the evolutionary process. Consequently, almost the entire book is an extended paean to the phenomenon of evolutionary convergence and parallelism. In this interpretation, evolutionary and functional constraints mean that only certain biological engineering solutions can work, and they have evolved more than once. Accordingly, we have the evolution of the camera-like eye in many unrelated groups, as well as such highly specialized features such as eusociality, echolocation, ovoviviparity, many different biochemical pathways, and examples too numerous to list here (since they take up most of his book, there’s no need to repeat them). From this, Conway Morris argues that many of the features that make us human have evolved in parallel at least once elsewhere, so the evolution of some combination of humanoid features is inevitable.

“Conway Morris argues that many of the features that make us human have evolved in parallel at least once elsewhere, so the evolution of some combination of humanoid features is inevitable.”

But is this really true? The camera-like eye did evolve more than once, but most of the features that make us human have not been repeated anywhere else in the animal kingdom — especially not our disproportionately large brains, and all the attendant cultural phenomena. (In answer to this conundrum, Conway Morris falls back on the relatively weak arguments about crude tool use and social development in other animals, but this has always been a poor analogy). Nowhere does his argument address all the other disparate factors that had to come together to make us human over the past 10 million years: just the right lineage of bipedal apes, living in the right combination of environments to promote culture and brain evolution, and surviving in a world that became increasingly inhospitable as the Ice Ages waxed.

Most of the convergences Conway Morris discusses seem impressive at first, but after a while, they remind the reader that most organisms are composed largely of unique features that are not convergent, and have never appeared more than once. Convergence is the rare exception in most groups of animals and plants, not the widespread rule. If all organisms were as highly convergent as Conway Morris suggests, then they would all tend to look alike, and we would never be able to tell them apart, let alone analyze their evolutionary relationships.

Conway Morris’ book is philosophically more in tune with the scientific literature of the 1950s and early 1960s, which viewed convergence as widespread, and despaired of ever telling whether groups had a unique evolutionary origin, because certain suites of anatomical features tend to appear more than once. But the whole thrust of systematic theory since the late 1960s has been driven by the cladistic revolution, which emphasizes unique evolutionary novelties, and underlined the fact that most organisms are not composed largely of convergent characters, but can be uniquely related to other organisms by these anatomical novelties. Indeed, cladistics has made it easier to recognize convergence (there’s a huge literature on this topic, where it is known as the phenomenon of homoplasy). Nevertheless, the overwhelming conclusion of all this analysis is that it’s a relatively rare phenomenon (except in a few groups that are very simple and stereotyped). Conway Morris, not surprisingly, has always been hostile to cladistics, so naturally he does not appreciate this perspective.

Let’s take Conway Morris’ argument seriously and ask how we could test his hypothesis. If the evolution of humans is inevitable, why didn’t it happen before in more than 600 million years of the evolution of multicellular animals? For example, the dinosaurs ruled the earth for over 150 million years, and some evolved very large brains relative to their body size (such as the dromaeosaurs, popularized by “Velociraptor” from the Jurassic Park movies and books). But they still didn’t evolve human intelligence, let alone complex social structure or culture and tools. In fact, paleontologist Dale Russell became a laughingstock of the profession when he commissioned an artist to make a sculpture of a “dinosauroid,” an imagined human-like descendant of the dromaeosaurs — it looked like something out of bad science fiction, and clearly showed his own anthropomorphic biases. It also underlined the improbability that any other lineage would ever evolve into something like us, even though the dinosaurs had over 100 million years to do so (while we only took 6 million years as a family to evolve).

More important, he misses Gould’s critical point about contingency. Would we even be discussing this issue if the dinosaurs had not died out, allowing mammals to then take over the world, producing a lineage of primates to evolve into us? The dinosaurs were not failures that were eventually pushed out by mammals eating their eggs. Instead, dinosaurs were supremely successful for over 100 million years, forcing mammals to exist in tiny and nocturnal niches the entire time, since both dinosaurs and mammals appeared side-by-side in the Late Triassic, about 200 million years ago. There’s no reason to doubt that dinosaurs would still dominate today if they hadn’t been wiped out by a rock from space, or great volcanic eruptions, or whatever did them in. This was a random event that could not have been predicted, despite the fact that dinosaurs were well adapted to the world of the Cretaceous, not poorly adapted creatures destined to failure, as the popular metaphor would have it.

And that indeed is the most crucial point of all that Conway Morris completely ignores, but which was central to Gould’s original argument. Once groups of organisms are established and develop a body plan and set of niches, biological constraints are such that convergence and parallelism can be expected. But the issue of who gets this head start in the first place may be more a matter of luck and contingency that has nothing to do with adaptation. Returning to the Burgess Shale example, what if Pikaia (and the lineage of primitive chordates leading to vertebrates) had not survived? It certainly doesn’t look like a sure winner compared to most of the more spectacular Burgess beasties. If it hadn’t survived, there would have been no vertebrates, and half the examples of convergence that Conway Morris details could not have occurred, because they are peculiar to the basic vertebrate body plan, and not shared in any other phylum.

Without vertebrates surviving the Cambrian, humans were not inevitable, since not even Conway Morris would argue that another group could have produced something like us. The jointed-legged phylum Arthropoda contains the most successful, diverse, and numerous organisms on the land, in the sea, and in the air today. This phylum includes the huge numbers and varieties of insects, spiders, scorpions, mites, ticks, millipedes, centipedes, and crustaceans. As numerous and diverse as they are, their habit of molting their exoskeletons when they grow means they can never exceed a certain body size — they would fall apart like a blob of jelly during their soft stage after molting without any skeletal support. (This, of course, is the reason why the huge insects in bad Sci-Fi movies are biologically impossible).

Mollusks? They may be supremely successful producing clams, snails, and squids in the oceans, and a few land snails, but their body plan yields few convergences with vertebrates, let alone humans. And phyla such as the Echinodermata (sea stars, sea urchins, sea cucumbers, brittle stars, and sea lilies) are even more closely related to vertebrates. Yet they are even less likely to produce a humanoid due to their peculiar specializations, such as a radial symmetry with no head or tail, spiny calcite plates, and lack of eyes. In addition, they lack any sort of circulatory, respiratory, or excretory system, so they are forever bound to marine waters of normal salinity. When you examine the list of survivors of the Cambrian world, the role of contingency in determining which body plans survived becomes more and more obvious — and the significance of the convergence that Conway Morris details in so many examples is moot.

Given that Conway Morris has taken this optimistic view of how easily nature can make a humanoid, one would expect that he is equally optimistic about the potential for life (and even humanoids) on other planets. But here he switches gears entirely, adopting a hard-boiled skepticism about the various estimates of the probability of life on other planets. He even casts doubts on the many models for how life originated in the first place. No SETI fan, he relentlessly squashes all the cheerful estimates based on the discoveries of new planets, or the ideas about the potential for primitive life on Mars, Io, Europa, or other bodies in our solar system. Instead, he follows the school of thought that argues that Earth is a unique and special place, the only one with conditions capable of evolving humans, or for that matter, life as we know it (the anthropic principle). In this view, only Earth has just the right combination of features (neither too hot nor too cold, also known as the “Goldilocks effect”). Conway Morris’ position seems very surprising, given his lack of skepticism for arguments about the inevitability of human origins. Usually, in a scientific trade book such as this, one expects a consistent tone toward all lines of argument, rather than such an abrupt shift of gears.

This change in tone makes one wonder about the underlying motivation of the author. He’s an optimist about the possibility that humans are the inevitable by-product of evolution, but a pessimist that any other planet has humanoids — how can someone take those two mutually contradictory positions? The mystery is answered in the last chapter, when the author reveals that the whole motivation for his position is religious. Early in the book he trashes and dispenses with the fundamentalist Creationists, but by the end his arguments appear equally slanted and biased. His final chapter bashes agnostic materialists like Gould and Dawkins and veers abruptly off into his own philosophical beliefs, musing about why he finds materialism and agnosticism inadequate to provide “meaning” to life.

At this point, one wonders if he is writing for the judges of the Templeton Prize, which is awarded to those who try to reconcile science and religion, rather than for an audience of people interested solely in scientific questions. He quotes religious scientists and Christian apologists such as C.S. Lewis extensively, and it’s clear that the entire book has been a thinly disguised defense for the traditional Christian viewpoint that humans are God’s handiwork and the pinnacle of creation, and that no other universes are so favored by God. At this point, the reader feels cheated. It’s one thing to read Christian apologists who select examples from science to support their point of view, and usually give away their biases from the start. But Conway Morris ends up being a stealth apologist in pretending that his argument that humans are special was motivated strictly by the scientific evidence. In reality, from the very beginning, his biases caused him to select evidence to support this opinion, and to miss the point of arguments that did not. I much prefer the candor of someone like Gould or Dawkins, who identify their biases up front, or for that matter, even the openly Christian writers, because at least they’re aware of their biases and not hiding them from the reader until the end.

Well written trade science books are a vanishing breed, marketed to smaller and smaller audiences who are easily suckered into reading and believing pseudoscientific babble and religious tracts masquerading as science. What a pity that such a distinguished scientist as Conway Morris (who has produced much excellent science in the past) falls into the latter trap with this book.

DR. DONALD R. PROTHERO is Professor of Geology at Occidental College in Los Angeles, and Lecturer in Geobiology at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. He earned M.A., M.Phil., and Ph.D. degrees in geological sciences from Columbia University in 1982, and a B.A. in geology and biology (highest honors, Phi Beta Kappa) from the University of California, Riverside. He is currently the author, co-author, editor, or co-editor of 25 books and over 250 scientific papers, including five leading geology textbooks and three trade books as well as edited symposium volumes and other technical works. He is on the editorial board of Skeptic magazine, and in the past has served as an associate or technical editor for Geology, Paleobiology and Journal of Paleontology. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America, the Paleontological Society, and the Linnaean Society of London, and has also received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Science Foundation. He has served as the Vice President of the Pacific Section of SEPM (Society of Sedimentary Geology), and five years as the Program Chair for the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. In 1991, he received the Schuchert Award of the Paleontological Society for the outstanding paleontologist under the age of 40. He has also been featured on several television documentaries, including episodes of Paleoworld (BBC), Prehistoric Monsters Revealed (History Channel), Entelodon and Hyaenodon (National Geographic Channel) and Walking with Prehistoric Beasts (BBC).

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

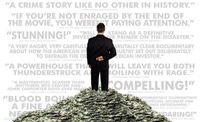

An Inside Look at an Inside Job

In this week’s Skepticblog post, Michael Shermer reviews Inside Job, a film produced, written, and directed by Charles Ferguson, produced by Audry Marrs, 108 minutes, narrated by Matt Damon. In this disturbing and often infuriating look at the financial meltdown, the Academy Award-nominated (No End in Sight) documentary filmmaker Charles Ferguson promises viewers an inside look into the “inside job” (use intended to convey criminality) that he believes explains the financial meltdown and subsequent recession.