In this week’s eSkeptic:

Swabbing a lipstick sample. Details: http://ahprojects.com/projects/dna-spoofing

Pieces of You

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 223

Do you know that everywhere we go, we all leave behind small traces of our own genetic material? In this week’s Skepticality, Derek speaks with Heather Dewey-Hagborg, an artist who has a massive curiosity about just how much of our personal information we leave behind in the form of DNA evidence. Heather went on a personal mission to find out if she could artistically replicate portraits of people from the DNA they leave behind everywhere they go.

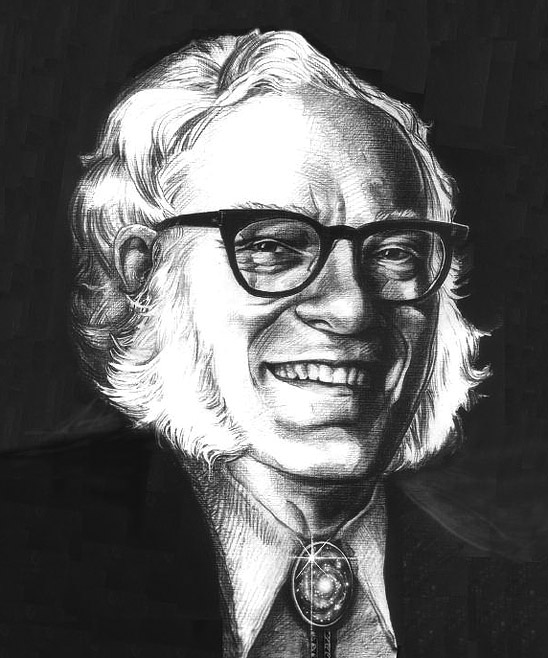

Illustration of Isaac Asimov, by Pat Linse

About this week’s eSkeptic

It seems fitting, on the first day of this new year, to feature an article from the premiere issue of Skeptic magazine (1992).

The timing of the premiere issue of Skeptic magazine and the loss of the greatest science educator and most prolific science fiction writer of the 20th century—Isaac Asimov—compelled a tribute to this great man, one of what was sure to be many in scientific and literary circles. Though the majority of Dr. Asimov’s readers never knew him on a personal level, we all knew him through his prodigious outpouring of books, articles, and essays. As he told one interviewer in reflecting upon life, death, and ideas: “I don’t have to worry about that, because there isn’t an idea I’ve ever had that I haven’t put down on paper.” To say that we were introduced to the worlds of science and science fiction through Isaac Asimov would be to parrot what is being said by scientists, scholars, and writers around the world. What better testimony to the man than to let the great honor the great?

In this week’s eSkeptic we present Steve Allen’s tribute to Isaac Asimov (January 2, 1920 – April 6, 1992).

A Tribute to Isaac Asimov

by Steve Allen

It is interesting that even so prominent a newspaper as the Los Angeles Times, in running a long and complimentary obituary story, one that started on the first page, referred to Isaac Asimov as a “science fiction virtuoso” and made no mention of his achievements as humanist thinker and writer.

I have the impression that the Times intended no slight whatsoever to the humanist movement in this matter but that its lack of reference to something so important to Asimov himself is an indicator of the general lack of attention paid to humanist philosophy by the American mainstream mindset. Indeed it has occurred to me that if it were not for daily attacks by right-wing fundamentalists, who are given to using the term secular humanist as they might use the phrase Satan or Communist, the non-theistic humanist movement would get almost no publicity at all. Fundamentalists would, of course, be more honest if they acknowledged that their true enemy is science, rather than any form of humanist opinion, given that the absurdities of strict Bible-literalism are firmly opposed by even those scientists who happen to be Christian or Jewish. It was Isaac Asimov’s great achievement to interest millions in science, and for that he will always deserve deep credit, particularly for having provided such a service in a time of the most monumental popular ignorance.

Journalists are sometimes kind enough to claim to be impressed by the fact that I have written 38 books. But my contribution to popular literature seems almost invisible when compared to Asimov’s achievement. Think of it—the man wrote almost 500 volumes, all connected in one way or another with science. Typing at a rate that professional secretaries would envy—90 words per minute—his output sometimes reached 4,000 words in a day.

Some writers, perhaps, are motivated, at least in part, by the simple desire to see their thoughts on paper in published form. But Asimov was energized by an earnest desire to make people think, to draw a sharp distinction between physical reality and undocumented nonsense. As many of his admirers know he rejected director Stephen Spielberg’s offer that he provide the screenplay for the modern film classic, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, apparently chiefly on the ground that the film was based on an uncritical acceptance of the theory that living creatures from other parts of the universe might have an interest in establishing contact with earthlings and that belief in UFOs is perfectly reasonable.

It might be argued that many of his own books represented pure fantasy, and indeed they did, but it was always fantasy undergirded by scientific principles and a clear understanding about degrees of likelihood.

Isaac realized that he was a born writer, but he was something else at least as important—a born reasoner. Reasoners are not, perhaps, radically different from the rest of the human race, but they have an insatiable thirst for evidence. And if he held to any views in the relative absence of evidentiary support, it was to treat them only as working hypotheses.

We are all much in Asimov’s debt for his tireless work on behalf of not only rationality but even simple common sense, both of which are in alarmingly short supply in today’s increasingly crazed and ignorant world.

Practically all Americans were gratified by the collapse of Marxist power in the Soviet Union, but until I received a fundraising letter from Asimov I did not realize the extent to which the relaxing of Communist restrictions—good in itself—has led to a veritable tidal wave of irrationality in the former Soviet sphere. American Christians generally react with a sort of goofy, mindless smile to any and all references to “freedom of religion” in Eastern Europe and Soviet Asia. But if they would examine the sharply-defined specifics of what is now happening, they would more properly be dismayed. While it is admirable that in America religious difference almost never lead to blows and gunfire, as they do in so many other parts of the world, ecumenical sentiment, when you get right down to it, cannot go very far, for the obvious reason that the fundamental differences that define the thousand- and-one religions are considered important beyond the possibility of compromise. To refer to a specific, most Americans agree that as U.S. citizens, Mormons are a likable, decent group while at the same time they hold Mormon theology in the greatest possible intellectual contempt. Do Catholics, Baptists, Methodists and Presbyterians, therefore, consider it a sign of progress that approximately 700 Mormon missionaries are now hard at work in the former Soviet Union?

Christians generally, and particularly conservatives, are horrified by the explosive growth of bizarre cults in recent years. One of the most dangerous of these is the Reverend Sun Yung Moon’s Unification Church, a fact on which the reader may seek further enlightenment from any recognized Christian theologian; but the Moonies, too, are now moving into Eastern Europe’s philosophical vacuum, and buying their way in at that. Another result of the new freedoms for religious belief is an invasion of Hare Krishna missionaries, something that depresses all thoughtful Christians and Jews. The bizarre theology of Jehovah’s Witnesses is viewed very dimly by all mainline Christian denominations, but the Witnesses now claim roughly 20,000 recent converts in Eastern Europe. Perhaps even more disturbing is the fact that The Children of God cult—one of the most vile and morally revolting religions in all history—has recently opened up for business in Bulgaria. Nor is the new irrationalist movement limited to religion. The city of Moscow alone has, at latest count, five formal study groups concentrating on UFOs and four organizations investigating not astronomy, alas, but astrology.

All of this and more, as I say, I learned from Asimov.

The best of science fiction is clearly respected as literature, and it is to Asimov’s eternal credit that he not only wrote what is generally considered the best sci-fi story of all but was only 21 when he did so. Called Nightfall, it describes popular reaction on a planet with six suns, when these bodies move into eclipse alignment, allowing its inhabitants, for the first time in their experience, to see the stars and hence at last perceive that the true glory of their universe far exceeds the pathetic limits drawn in their traditional documents.

No one becomes as successful as Asimov without drawing the attention of a few detractors. Asimov’s were those who are uncomfortable in the presence of clear thinking. ![]()

NEW ON MICHAELSHERMER.COM

Confessions of a Speciesist

Could the presumption that nonhuman animals’ interests are less important than human interests be merely a prejudice — similar in kind to prejudices against groups of humans such as racism? In Michael Shermer’s January 2014 ‘Skeptic’ column for Scientific American, he asks “Where do nonhuman mammals fit in our moral hierarchy?”

For your enjoyment, we’ve put together a list of the top 10 most shared articles on skeptic.com from 2013. Follow the link below to see the list, read a brief introduction, and click the titles to read the articles.

Richard Dawkins, On Demand

The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution

A disturbingly large percentage of the American and British public don’t think that evolution is true. In fact, they actively abhor the idea, since it seems to contradict the Bible and diminish the role of God. So Dawkins decided to write a book, The Greatest Show on Earth, for these history-deniers, to dispassionately demonstrate the truth of evolution beyond sane, informed, intelligent doubt. In this lecture, based on the book, Richard Dawkins lays out the evidence that evolution is true.

Rent this video for only $3.95

or explore the entire series.

INSTRUCTIONS: Click the button above, then click the RENT ONE button on the page that will open in your Internet browser. You will then be asked to login to your Vimeo account (or create a free account). Once you complete your purchase of the video rental, you will then be able to instantly stream the video to your computer, smartphone, or tablet, and watch it for the rental period.