The following is a book review of Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking by Malcolm Gladwell. (Little Brown. ISBN: 0-316-17232-4)

This review was originally published as “You Can Judge This Book by Its Cover” in the New York Sun, February 2nd, 2005.

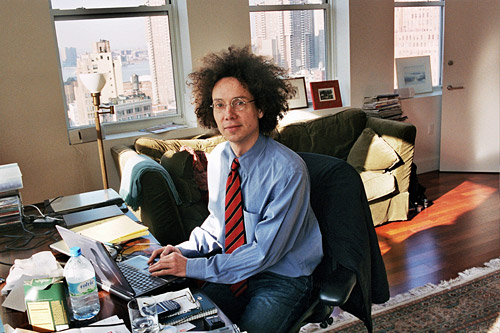

Malcolm Gladwell, photographed by Brooke Williams

In the Blink of an Eye:

Why Messrs. Spock, Holmes, and Data Were Wrong

a book review by Michael Shermer

Anyone who does a lot of public speaking knows there are certain questions that inevitably arise from the audience in a Q&A. In my case, lecturing on pseudoscience and the paranormal, I am almost always asked: What is my position on the afterlife? (“I’m for it”), have I ever encountered a mystery that science cannot explain? (“Paris Hilton”), and have I ever been skeptical of something that turned out to be real? For this final question I have a serious answer: intuition.

As a skeptical scientist, I have always treated with disdain the notion that one can intuit a truth about reality. Scientists should employ the logic of Mr. Spock, the deductive reasoning of Mr. Holmes, and the rational calculus of Mr. Data. Hunches, guesses, insights, feelings, and intuitions lead to misdirection and error. Thinking things through rationally and systematically is the royal road to reality.

Well, I was wrong. It turns out there’s a lot more to thinking than meets the experimental eye, and Malcolm Gladwell has penned an absolutely delightful summary of all the important research in the study of intuition. His title, Blink, is apt, for we humans have a remarkable—and heretofore unproven—capacity for making judgments in the metaphorical blink of an eye that are often superior to those we might have made had we taken the time to assess all possible variables.

Gladwell begins with the fascinating story of how the Getty Museum got taken by a forged Kouros, a sculpture of a youth allegedly carved in 6th-century B.C. Greece. Despite an intuitive hunch many of its experts had that there was something about the piece that was not quite right, there was no smoking gun of fakery any one could identify. So the artwork was purchased, and only later was it exposed as a fake. The best assessment of whether a work of art is a forgery, it turns out, is the first impression an art expert has on seeing it, not necessarily a battery of scientific tests. For example, one of the art experts—Thomas Hoving, the former director of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art—later recalled that the first word that popped into his mind when he saw the Kouros was “fresh.” Although he could not say precisely what about the statue was fresh, it was a general feeling he had about it. “I had dug in Sicily where we found bits and pieces of these things. They just don’t come out looking like that. The Kouros looked like it had been dipped in the very best café au lait from Starbucks.”

What is happening here is nonrational (not irrational) analysis at a level below conscious awareness. Students who view three 10-second video clips of a professor, for example, give roughly the same ratings of that professor’s effectiveness as those students who actually took the course. (This may also mean that student evaluations are actually based on first impressions rather than extensive analysis.) The same effect—called “thin slicing”—can be seen in dating, where first impressions are everything, as is well known by those who have tried “speed dating,” a trendy way to meet people, in which each of multiple “dates” in one evening lasts only six minutes. Thin slicing is intuitive thinking, “thinking without thinking” as Gladwell puts it. That’s not quite right, however, as I suspect it is more of a subtle, unconscious (or subconscious) form of thinking that we just don’t know that much about as yet. We are collecting data about a person or situation, and that data is being analyzed somewhere in the brain. How precisely that is being done remains a mystery.

Evaluating whether someone is trustworthy or not, or whether someone is lying or telling the truth, is more accurately done by intuitive “feel” in a brief interaction than by subjecting them to a polygraph test. The best predictor of how well a psychotherapist or marriage counselor will work for you is the impression you have of that person in the first five minutes of the first session. University of Washington psychologist and marriage counselor John Gottman, who has reversed the process, can predict with 95% accuracy whether a marriage will last or not after observing the couple for only one hour. Contempt for one’s spouse, for example, is a powerful predictor of a doomed marriage, and rolling one’s eyes when one’s spouse is speaking, is a proxy for contempt. A lot can be read in the blink of an eye.

We are especially good at snap judgments when it comes to human relations, because we evolved as a social primate species living in small tribes in which social relations were extremely important. We needed (and still need) to know whom we can trust and whom we cannot trust; in the prehistoric world of our Paleolithic environment we had only our wits and intuitions, the “sense” or “feeling” we had for someone’s trustworthiness, to rely on. The social calculus was not the slow and systematic logic of analysis; it was (and is) the subtle and fast feeling of a felt emotion. That “feeling” is the expression of an internal computation whose consequences are important.

This explains the interesting results of an experiment conducted by the psychologist Samuel Gosling. He rated 80 subjects on the “Big Five” personality scale (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness to experience). He found a high correlation with similar ratings of the subjects done by their best friends — no surprise. But then he sent total strangers into the dorm rooms of the subjects and gave them 15 minutes to answer questions about the person who lived there. The strangers were not as good as the best friends in evaluating extraversion and agreeableness, but on conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness to experience, the strangers knew the subjects better than their best friends!

Some of the research findings on what might be called “the blink effect,” so well encapsulated by Gladwell, are startling. The best predictor of whether a physician will be sued for malpractice is not the doctor’s training, credentials, or track record, but a subjective evaluation by observers of short clips of conversation between doctor and patient. Physicians who seem warm and empathetic—traits that can be sensed in a blink—are less likely to be sued by their patients, regardless of the number of errors they commit. As one lawyer explained it, “In all the years I’ve been in this business, I’ve never had a potential client walk in and say, ‘I really like this doctor, and I feel terrible about doing it, but I want to sue him.’ We’ve had people come in saying they want to sue some specialist, and we’ll say, ‘We don’t think that doctor was negligent. We think it’s your primary care doctor who was at fault.’ And the client will say, ‘I don’t care what she did. I love her, and I’m not suing her.’”

Unfortunately, in what Gladwell calls “the dark side of blink,” we sometimes make snap assessments of people based on inappropriate criteria, such as their gender or race. Research with the Implicit Association Test has shown that we form connections between things faster when there is already an association, such as between female and laundry, home, kitchen, housework, and babies; and between male and professional, merchant, capitalist, corporation, and entrepreneur. Even more sinister are the associations of African-American or European-American with such adjectives as hurt, evil, glorious, and wonderful. “It turns out that over 80 percent of all those who have ever taken the test end up having pro-white associations,” Gladwell explains, “meaning that it takes them measurably longer to complete the test when they are required to link good things with black people than when they are required to link bad things with black people.”

Gladwell took the test and was rated as having “moderate automatic preference for whites”; “but then again, I’m half black,” he points out. Meaning what? “What it means,” he concludes, “is that our attitudes towards things like race or gender operate on two levels. First of all, we have conscious attitudes. These are our stated values, which we use to direct our behavior deliberately.” The IAT, on the other hand, measures “our racial attitudes on an unconscious level—the immediate, automatic associations that tumble out before we’ve even had time to think. We live in North America, where we are surrounded every day by cultural messages linking white with good.”

Blink is packed with examples of such intuitive processes, a thoughtful and thought-provoking look into both the light tunnel and the dark well of our minds. But I wish to praise it on another plane as well.

There are, roughly speaking, three levels of science writing in our culture: (1) technical (peer-reviewed papers, monographs, and university press books written by and for professional scientists); (2) popular professional (essays and articles in popular magazines and trade press books written by scientists for both scientists and moderately informed general readers — Stephen Jay Gould, Richard Dawkins, and Jared Diamond come to mind); (3) popular general (essays, articles, and books by journalists and science writers for completely uninformed readers).

We live in the Age of Science, and all three levels are vital for the dispersal of scientific knowledge to an educated democracy. Sadly, too many professional scientists think level one is the only legitimate form of science writing, and that anything else is simply “dumbing down.” For his presentation of science to hundreds of millions of people, the astronomer Carl Sagan was slammed by his peers, denied tenure at Harvard, and rejected by the National Academy of Science. Yet he never stopped producing peer-reviewed articles, averaging one a month for his entire career.

Gladwell is presenting science at level three, where it is most needed, and where good writing is most vital. He has the ability to synthesize a large body of scientific data into a highly readable, page-turning narrative, and to convert the raw numbers of research and statistics into meaningful facts for our personal lives. I thought he did this brilliantly with The Tipping Point, and I think he does it even better in Blink. For this feat all of us in the scientific community should be grateful, because the craft of writing good science is just as important as the skill of producing good science.

This Weekend:

Brain, Mind & Consciousness

The Skeptics Society Annual Conference

Friday, Saturday, Sunday, May 13–15

at the Westin Resort & Hotel

and the Beckman Auditorium, Caltech, Pasadena, CA

Letting Go of God

Julia Sweeney

Sunday, May 15th, 3:00–5:30 pm show

Hudson Backstage Theater, Hollywood, CA

followed by dinner at Julia’s home

For more information about these events and lectures,

see www.skeptic.com.