In this week’s eSkeptic:

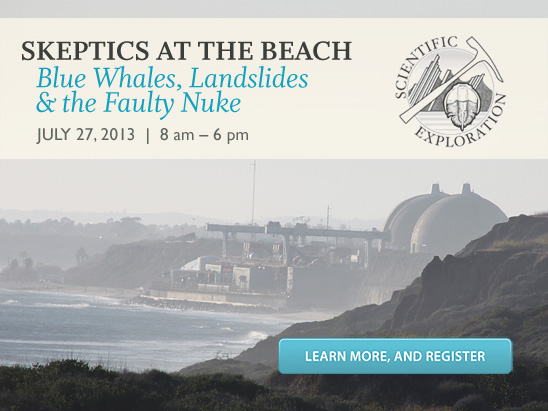

Skeptics at the Beach

↑ Image not showing up? View this announcement in your web browser.

BEAT THE SUMMER HEAT and join the Skeptics Society for a field trip to the beach! We will take a whale-watching trip out of Dana Point at the height of blue whale season. Our journey to the sea will include Ocean Institute scientists who will introduce you to the local marine wildlife; including an astounding variety of fish, microscopic plankton, and the animals that live in sediment retrieved from the ocean floor. Encounter a pod of playful dolphins or witness the majesty of a traveling whale. Before our cruise, we will also visit the marine aquarium at the Ocean Institute. In the morning, we will visit San Onofre State Beach and see marine terraces, beach processes, landslides, and the fault near the San Onofre nuclear reactor. At Dana Point, we will also see evidence of giant submarine gravity flows, and geological traces of a lost continent that used to lie offshore millions of years ago. Come join us for an amazing day in the cool beach weather!

Click an image to enlarge it.

Photos of San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station, south of San Clemente, CA, and nearby cliffs by Ed Pastor. Wildlife photos courtesy of the Ocean Institute, Dana Point, CA.

What’s Included?

Trip cost includes all transportation, lunch, all fees and admissions, guidebook and the guided tour lectures. Come join us for an amazing day!

Our Tour Leader, Dr. Donald R. Prothero,

Receives the 2013 James Shea Award

Dr. Donald R. Prothero recently retired from his professorship at Occidental College in Los Angeles, CA after 34 years of teaching in order to concentrate on his writing and consulting. Dr. Prothero is an indefatigable advocate for geology and paleontology, which he combines with a passion for communicating science to the public. Notably, he has served as a consultant for Discovery Channel, History Channel and National Geographic specials. He frequently gives public talks and presentations to groups interested in Earth science, including presentations to the NYC Skeptics, The Bone Room in Berkeley, CA, Bay Area Skeptics, and the Natural History Museum of L.A. County. Dr. Prothero is a prolific writer; he posts a weekly blog at Skepticblog.org and has published over 30 books. His talks and blogs focus on debunking pseudoscience and defending the science of evolution and climate change. He has made numerous contributions to advancing his fields of expertise by publishing in technical journals. He has authored and co-authored 259 papers, including papers in the following peer-reviewed journals: Nature, Paleobiology, Geology, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, Journal of Paleontology, Journal of Geology, Science, Journal of Geological Education, Palaios, Paleoceanography, and Geotimes to name a few. Prothero has served as a reviewer and editor throughout his career. He served as adjunct editor for Paleobiology and he has also served on the editorial boards of Skeptic magazine and for Geology. In addition, he has served as technical editor for Journal of Paleontology and as a consulting editor for the McGraw-Hill Yearbook of Science and Technology. In recognition of Dr. Prothero’s exceptional contributions in the form of writing and editing of Earth science materials, the National Association of Geoscience Teachers (NAGT) is proud to award him with the 2013 James Shea Award.

Questions?

Email us or call 1-626-794-3119 with a credit card to secure your spot.

See You at The Amaz!ng Meeting 2013!

Daniel Loxton encourages skeptics to register for The Amazing Meeting (TAM) 2013 conference in Las Vegas, and especially to attend the skeptical history workshop that he will be moderating.

Use promotional code SKEPTICMAGAZINE and SAVE $25 on the price of TAM registration.

About this week’s eSkeptic

We are surrounded by information: on TV, the Internet, in magazines, books, and emails from friends, family, commercial advertisers, politicians and other advocates making extraordinary claims. In this week’s eSkeptic, Donna L. Halper discusses some examples of how society has been duped, and shares some media literacy rules (skepticism and critical thinking) that will help you evaluate and assess claims for accuracy. This article appeared in Skeptic magazine issue 17.4 (2012).

Illustration copyright © 2012 by Nancy Norcross-White

How To Be a Skeptical

News Consumer

by Donna L. Halper

Even the most skeptical among us have had this happen: A friend or relative forwards an e-mail from an organization with a safe-sounding name (“The Clean Air Initiative,” “The Center for Consumer Freedom”), but the e-mail is filled with scary assertions, usually of a political nature. If the Obama-care health bill is passed, Grandma will face a “death panel” that will decide if she lives or dies; if Barack Obama is re-elected, America will soon become a Marxist or Muslim nation. Some of the chain-emails are obvious partisan propaganda (There is little if any chance of any president, whether Barack Obama or anyone else, imposing Marxism or Islam on America; and the Affordable Care Act [its official name] contains nothing about “death panels”). But some are more subtle, relying on truncated (or fake) quotes, or manipulated facts. And while we most often see these sorts of false (but credible-looking) assertions made during elections, they can also be generated by interest groups trying to peddle unproven cures for diseases, or anti-science advocacy groups who oppose fluoridation or vaccination.

I’m a professor of media, and I focus on critical thinking in every class I teach; but it’s not just college students who can benefit from a skeptical approach to what they see from both print and online sources. Every school—from elementary right on up—should encourage students to become media literate: the ability to evaluate and assess the claims made by commercial advertising as well as by politicians and advocates. We are supposed to live in an “information society,” but sadly, much of what we see and hear is not entirely accurate. As a researcher, I’ve noticed the tendency on the Internet for some “fact” to be posted on one site and then reposted hundreds of times, as if the amount will somehow prove it’s true. As any student of philosophy knows, this is an aspect of Argumentum ad Populum, or the Bandwagon effect—if millions of people believe X, it must be true. Or, as my students will often tell me, they saw it on Wikipedia (or some other frequently read site), so it must be true.1

In fairness to Wikipedia, although I much prefer encyclopedias where the articles are signed (so that I know who wrote the piece), some of their articles are quite thorough and informative. But others contain well-traveled myths and rely on volunteers to correct them. It’s often a losing battle. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve refuted the myth that radio station KDKA was the first station in the United States (or in the world, depending on which source you read). This is a durable myth, promoted very effectively in the 1920s by their corporate owner—Westinghouse—which had an impressive publicity department. And that is rule number one of media literacy: Know who created the message, so you can factor in whether the creator was pushing a special agenda. Not all agendas are malevolent. Westinghouse may have indeed believed their station was unique and the company sought to promote that fact. But they were not alone: the Detroit News (which owned a station in Detroit), AMRAD (owners of a station in Medford Hillside MA), and several other American companies had stations on the air at that time, as did the Marconi company in Montreal, and these owners certainly wanted to spread the word about what their stations had done. Yet Westinghouse was so effective in asserting KDKA’s primacy that to this day, the claim is treated as historical fact by otherwise reputable textbooks.2 History can indeed be written not just by the winners, but by powerful publicists.

Many contemporary media critics treat the proliferation of fake news and erroneous information as something modern, but the truth is we can trace it back several hundred years. In some cases, the misinformation was even intentional, created in order to sell newspapers (a technique still used by today’s tabloids). A good example occurred back in late August 1835, when the New York Sun published an authoritative-looking piece about a famous British astronomer who had discovered life on the Moon, thanks to an amazing new telescope. It was a time when a college degree was only available to the privileged few, and the Sun used techniques that are still being used even now: they cited an “expert,” used scientific jargon, and claimed that his “discovery” had appeared in a prestigious overseas journal. In an era where fact-checking would have been difficult, few readers asked the questions a skeptic might ask today: Was the expert a real person? Did the expert really write what the article claimed he wrote? Did the journal exist, and was his work really published in it? The case came to be called the Great Moon Hoax and a good summary of it can be found on the website of the Museum of Hoaxes.

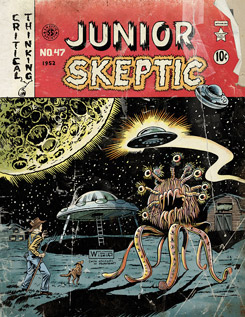

Read about Aliens Invasions in the current issue of Junior Skeptic magazine. In this issue, Daniel Loxton answers the questions: Where did we get our ideas about being attacked from “outside”—from other lands, or from outer space? How has this idea been expressed in stories? How do exotic species here on Earth “invade” new regions? Can life forms from one planet really invade another? NOTE: Junior Skeptic is physically bound within every issue of Skeptic magazine.

Of course, even in 1835, there were skeptics (including some at rival newspapers), and eventually, the story was shown to be an elaborate fraud. But this would not be the only time a media outlet hoaxed the public: the Orson Welles’ “War of the Worlds” broadcast from late October 1938 is another frequently cited example. In this case, the broadcast was a radio adaptation of H.G. Wells’ science fiction novel about a Martian invasion of earth. But so realistic was the presentation, complete with scary sound effects (including the special tones used by radio stations when airing a news bulletin), that many listeners were certain they were hearing news, rather than a play. The effect was further enhanced by the deep-voiced and very serious narrator (Welles), who kept providing new and more frightening “details” about the “invasion.” Today, we know that reports of mass panic after the broadcast were exaggerated (the show didn’t even air in some large cities, Boston among them),3 but it sounded so authentic that millions of listeners were convinced the United States was under attack from Martians, and there is evidence that some people did in fact run from their homes in terror, convinced the end was near.4 The broadcast was a mixed blessing for Welles, whose Mercury Theater program previously suffered from very low ratings. After the “War of the Worlds” hoax, the show got lots of attention, but not all of it favorable—many people were furious that they had been fooled, and some critics demanded that such programs be banned. As for Welles, he claimed to be shocked, shocked that anyone would believe a science-fiction play, and yet many people did. And to this day, there are programs on television about “ghost-hunting” or about houses that are allegedly haunted; and because they are often well-produced and make good use of special effects, gullible viewers think they must be true.

Where Can You Go

to Fact-check?

One of my favorite reference volumes is the Yale Book of Quotations, edited by Fred R. Shapiro. If your local library doesn’t have the newest edition, it should. Many (though not all) quotes found on Wikiquotes are wellsourced, but I would still cross-check with other encyclopedias, just to be sure; Google books has many original books on line, and scholarly databases such as JSTOR (the “Journal Storage,” available in many college libraries) are excellent for providing older quotes in their original context. As for online sources, I recommend www.snopes.com (this site checks chain e-mails as well as political myths and fake quotes); similar and also good for general myths is www.urbanlegends.about.com. For politics specifically, I use www.politifact.com and www.factcheck.org. And, of course, skeptical sites such as www.skeptic.com, www.randi.org, www.cfi.org, and www.skepdic.com are also useful resources, as is www.skepticblog.org. And I am pleased that several newspapers, notably the Washington Post, now have regular columns where stories and claims from political ads are factchecked: http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/factchecker.

Unfortunately, there have been many times when the media themselves gave credence to pseudoscience, and not just to sell papers or get bigger radio and TV ratings. It has been noted by some critics that far too often, journalists who lack a background in science simply repeat what a press release claims to be true, or quote from someone else’s article without checking into its veracity. Also, in fairness to journalists, the job of any reporter is to tell a story, and when confronted with a very dense and jargon-filled academic essay, the tendency is to find a way to give it more excitement and mass appeal. The media’s misadventure with science is nothing new: in 1922–1923, many otherwise reputable newspapers were eagerly touting a new “miracle man”—a doctor from France named Emile Coué, who could cure people by teaching them positive thinking, and having them chant “Every day, in every way, I’m getting better and better.”5 Of course, Coué was not a doctor (at most, he was a pharmacist), and there was little objective evidence of any cures, but that didn’t stop reporters from going to his presentations and marveling at the people who were no longer (pick one) blind, lame, asthmatic, or terminally ill. By most accounts, Coué was quite charismatic, and a number of reporters who saw him seemed genuinely convinced that he was a miracle-worker.6 The many articles praising him led to the emergence of an entire cottage industry, with radio programs devoted to American “experts” in the Coué method, and schools that claimed to teach anyone how to derive amazing results.7 Radio also became home to a number of other frauds: fortune tellers, faith healers, and assorted other quacks, some of whom were criticized by the press, but most of whom became very popular anyway. One of the most famous examples was Dr. John R. Brinkley, another fake physician, whose “cure” for impotence involved goat gland implant surgery for men, many of whom underwent the painful procedure in hopes of improving their performance in the bedroom. The story of his successful radio career and his eventual downfall, is well told in R. Alton Lee’s 2002 book The Bizarre Careers of John R. Brinkley.

These days, it’s not just scary chain e-mails that should warrant skepticism and critical thinking. Politicians love to give non-threatening or positive names to laws that would otherwise inspire debate and controversy. Two good examples: After 9/11, Congress quickly passed the PATRIOT Act, which evoked emotions of standing up to terrorists and showing pride in being an American. But the act, which was an acronym for “Providing Appropriate Tools Required (to) Intercept (and) Obstruct Terrorism,” contained some provisions that are still being debated today, and a number which civil libertarians and privacy advocates have vehemently opposed.8 Another example was the 2002 “Healthy Forests Act,” which certainly sounded like something worth doing: who isn’t in favor of healthy forests? But when skeptics, many of whom were also passionate about the environment, delved further into this act, which was a priority for President Bush, they found it actually encouraged more logging in national forests. Whether logging is a good thing or not, the name did not reflect the provisions the act contained.9 Another media literacy rule: Find out who is actually behind the innocuous-sounding name, so you can decide whether the facts they are presenting can be trusted.

And then there are fake quotes. Did you know that the Founding Fathers said America is supposed to be a Christian nation? Did you know that they also insisted that a nation that did not rely on the Bible would never prosper? If you believe the chain e-mails sent by conservative Christian advocacy groups, often citing the work of David Barton (an evangelical Christian minister, former co-chair of the Republican Party of Texas, and the founder of WallBuilders, a Texas-based group that claims the separation of church and state is a myth) then you have probably been told that the American founders were opposed to the government helping the poor (especially the undeserving poor), and that they especially feared the rise of socialism.10 In journalism, it’s a truism that “If your mother says she loves you, check it out.” In other words, just because you got the quote from Mom, that doesn’t mean she had accurate information. I always encourage my students to fact-check quotes, because even if the person actually said it, often the quote is taken out of context (this can frequently be seen in political ads, where both parties try to make their opponent look bad by using a particular quote to fit a narrative of what a horrible person he or she is). The Internet has been a great benefit in finding actual sources for quotes, but it has also been part of the problem: It is very easy to put up an authoritative-looking website with a very ideological agenda. When it comes to quotes, skepticism is especially needed, to make sure that: (a) the person really said it, and (b) the context supports the way the quote is being used. This is not just a good rule for political ads: it even applies to classic movie quotes: The words “Play it again, Sam” were nowhere to be found in the movie “Casablanca,” but millions of people think that’s what Ingrid Bergman said.11 Thus, in order to make sure your evidence is accurate, take the time to fact-check the quotes, even the ones that “everybody” believes to be accurate.

The bottom line is that it pays to be skeptical because so much of what we encounter in the media turns out to be entirely false, mythically inflated, politically charged, ideologically loaded, or a mixture of facts and fiction. And as we see with the “Birthers,” that percentage of the public who insist that Barack Obama was actually born in Kenya, no matter how much credible evidence is presented that he was born in Hawaii, some people have trouble distinguishing between verifiable fact and unproven opinion.12 But this is not just a problem that affects Birthers, climate change deniers, or people who think we never walked on the Moon; as we see every day, it is surprisingly easy to misinform the average person. Back in 1938, after the furor over “War of the Worlds,” the Boston Globe’s pseudonymous “Uncle Dudley” gave readers some good advice, words that still resonate today. He said that we all have a duty to think for ourselves and not rush to judgment just because of something we heard in a broadcast. And whether the information is in print or broadcast, he concluded, “…a robust will to doubt, to examine statements, and to measure them alongside common sense and experience… is a hallmark of the civilized mind.”13 ![]()

References

- Discussion of “bandwagon” and other propaganda techniques is derived from the Institute for Propaganda Analysis (1937–1942). While some of its assertions may seem dated, the basic ideas are still relevant, and have been updated for a new generation by Dr. Aaron Delwiche of Trinity University, San Antonio TX. The site, “Propaganda Critic,” contains useful information about recognizing and debunking all kinds of propaganda. http://www.propagandacritic.com

- For example, in The Broadcast Century and Beyond (5th edition, Focal Press, 2010), Rober t L. Hilliard and Michael C. Keith, writing about another claimant to being first, Charles “Doc” Herrold, an inventor and engineer from San Jose CA, state: “Although some historians say that Herrold’s station, ultimately called KQW, is the country’s oldest, it did not broadcast to the general public on a regular schedule; that designation is acknowledged to belong to KDKA in Pittsburgh, which began doing so more than a decade later” (p. 10). But there is documented evidence, including newspaper articles and reception reports from listeners, that both the Detroit News station (today WWJ) and the Medford Hillside station (first called 1XE, later WGI—long defunct, but widely repor ted about in the Boston newspapers of its day) were on the air before KDKA, had regular schedules, and were heard by the general public. For example, the Detroit News printed letters from the audience, which back then was largely comprised of ham radio operators and their families, after its station, then known as 8MK, broadcast election returns in late August 1920: “Wireless Stations Praise News Radiophone Service,” Detroit News, 2 September 1920, pp. 1, 2. It is also a myth that KDKA had the first “commercial” license; such a license did not exist until 1921, and another Westinghouse station, WBZ radio (then in Springfield MA, today in Boston) received the first one.

- Albert D. Hughes, radio critic for the Christian Science Monitor, noted that WEEI, the Boston station that normally carried the Mercury Theater, had decided to schedule a different program in that time period. “Radio Scare: Boston Misses ‘Martian Raid’,” Christian Science Monitor, 1 November 1938, p. 12.

- See, for example, the Associated Press repor t, picked up by many newspapers, “Radio Play Terrifies Nation: Mars Invasion Thought Real,” Boston Globe, 31 October 1938, p. 1; and “Hysteria Sweeps U.S. As Mar tian Soldiers Attack in Radio Play,” Springfield MA Republican, 31 October 1938, pp. 1–2. It is worth noting that despite claims of widespread panic, when George Gallup polled “men and women in all parts of the country” to ask their opinion of the year 1938’s top stories, the “War of the Worlds” incident did not even rank in the top ten. “Czech Crisis Big Event of 1938,” Boston Globe, 1 January 1939, p.4. And modern scholars have refuted many of the claims made by early newspaper reports. Two excellent books on the subject of what really happened are Getting It Wrong: Ten of the Greatest Misreported Stories in American Journalism by W. Joseph Campbell (University of California Press, 2010), and The Martians Have Landed! A History of Media-Driven Panics and Hoaxes, by Robert E. Bartholomew and Benjamin Radford (McFarland, 2012).

- “French Exponent of Auto-Suggestion Prepares for Coming Visit to America.” (Reno) Nevada State Journal, 24 December 1922, p. 6.

- Typical of these effusive and uncritical articles were one by Hayden Church, “From Obscure Druggist to Foremost Psychologist.” Atlanta Constitution, 4 June 1922, p. C9; and “Behind Closed Doors of Coué’s Famous Clinic—Showing Marvelous New Method.” Boston Post, 13 August 1922, p. 41.

- Among them was a radio actress named Mona Morgan who did several broadcasts about the Coué method over radio station WJZ in Newark; she told her audience how a listener had written to say these broadcasts had helped cure his rheumatism. “Girl Teaches Coué by Radio.” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 2 January 1923, p. 3. And in Portland, Oregon, Dr. Innes V. Brent, dean of the Brent School of Applied Psychology, made his claims of amazing cures over station KGW, answering questions from listeners about the results they would surely receive. “Broadcasting from KGW.” Portland Oregonian, 11 January 1923, p. 11.

- Vincent Warren, Executive Director of the Center for Constitutional Rights, whose organization vehemently opposed the PATRIOT Act, has written a good essay about the impact of the act’s most controversial provisions: “The 9/11 Decade and the Decline of U.S. Democracy.” https://ccrjustice.org/the911decade/declineofdemocracy

- The story of the Bush administration’s skill at giving innocuous names to policies environmentalists considered radical is well-told in the book George W. Bush’s Healthy Forests: Reframing the Environmental Debate, by Jacqueline Vaughn and Hanna Cortner (University of Colorado, 2005).

- Numerous reputable journalists have debunked David Barton or noted that he has no scholarly background in history; they have also noted with alarm his ability to persuade certain school districts and home-schooling parents to make use of his curriculum. Among several recent articles on Barton are: “American Scripture: How David Barton Won the Christian Right,” by Yoni Appelbaum, Atlantic Monthly (May 2011) http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2011/05/americanscripture-how-david-barton-won-the-christian-right/238603/ “Using History to Mold Ideas on the Right,” by Erik Eckholm, New York Times, 5 May 2011, p. A1, and online at http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/05/us/politics/05barton.html And also worth reading is Chris Rodda’s book Liars For Jesus: The Religious Right’s Alternate Version of American History (BookSurge, 2006).

- This and other mythic quotes can be found in They Never Said It: A Book of Fake Quotes, Misquotes and Misleading Attributions by Paul F. Boller Jr. and John George (Oxford University Press, 1989).

- The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life conducted a survey in June and July 2012 which found that 31% of respondents said they did not know President Obama’s religion and 17% said he is a Muslim: http://www.pewforum.org/Press-Room/Press-Releases/New-Poll-Finds-Little-Voter-Discomfort-with-Romney’s-Mormon-Religion.aspx. And a February 2011 poll of 400 Republican primary voters, conducted by Public Policy Polling, found that 51% doubted President Obama was born in the United States. http://www.politico.com/news/stories/0211/49554.html. A CNN/Opinion Research Poll of more than 1000 Americans, conducted in March 2011, showed that a total of 25% thought the president was either definitely or probably born in another country: http://i2.cdn.turner.com/cnn/2011/images/03/29/rel4k.pdf

- Uncle Dudley, “Radio and Skepticism.” Boston Globe, 1 November 1938, p. 14.