In this week’s eSkeptic:

NEW SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN COLUMN

ClimeApocalypse!: Or just another line item in the budget?

The world has many problems: armed conflicts, natural disasters, hunger, disease, education, and global warming to name a few. Which problem should we tackle and how much should we spend?

Credit: Dustin Aksland

The Elementary Remedy

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 237

This week on Skepticality, Derek talks with Thomas Goetz, past Executive Editor for Wired magazine, co-founder of Iodine, and author of healthcare related books. Thomas’s latest book, The Remedy, is about Robert Koch, the father of modern bacteriology, his quest to find the cause and cure for tuberculosis, and the relationship between Koch and Arthur Conan Doyle.

DISTINGUISHED SCIENCE LECTURE

Dr. Donald Prothero — Abominable Science & Reality Check

Geologist, paleontologist, evolutionary theorist and social activist in the name of science and skepticism, Dr. Donald Prothero talks about his two new books that deal with battles over evolution, climate change, childhood vaccinations, and the causes of AIDS, alternative medicine, oil shortages, population growth, and the place of science in our country. Many people and institutions have exerted enormous efforts to misrepresent or flatly deny demonstrable scientific reality to protect their nonscientific ideology, their power, or their bottom line. To shed light on this darkness, Prothero explains the scientific process and why society has come to rely on science not only to provide a better life but also to reach verifiable truths no other method can obtain.

And on the lighter side, Prothero talks about how large numbers of people believe in demonstrably false phenomena, from UFOs and ESP to Bigfoot and the Loch Ness monster. Even though these fictions have been repeatedly debunked and discredited, they persist in the human imagination and influence our beliefs and our society. Prothero gives an entertaining and educational overview of a variety of cryptids, presenting both the arguments for and against their existence and systematically challenging the pseudoscience perpetuating their myths.

You play a vital part in our commitment to promote science and reason. If you enjoyed this Distinguished Science Lecture, please show your support by making a donation.

Who’s Lying, Who’s Self-Justifying?

Origins of the He Said/She Said Gap

in Sexual Allegations

For those of you who missed The Amazing Meeting 2014, we present another lecture from that event, by one of Skeptic magazine’s columnists, Dr. Carol Tavris. Tavris writes “The Gadfly” column in each issue beginning this year.

The Woody Allen sex scandal of 2013 triggered a national conversation on whom to believe, with people lining up on each side as if they knew what really happened. Based on recent research on how people navigate the often tricky waters of sexual negotiation, Dr. Carol Tavris shows that it is entirely possible in some sexual assault cases neither side is lying, but instead both sides feel justified in their positions. This talk was considered one of the best ever given at TAM. (Read the article on this same topic that appeared in Skeptic magazine issue 19.2.)

Dr. Carol Tavris is a social psychologist and coauthor, with Elliot Aronson, of Mistakes Were Made (but not by me): Why We Justify Foolish Beliefs, Bad Decisions, and Hurtful Acts). Order the book, or order lecture on DVD, or rent the lecture on Vimeo on Demand.

About this week’s eSkeptic

Tattletale, Ratfink, Stool Pigeon, Snitch, Informer, Canary, Turncoat, Bigmouth, Busybody, Fat Mouth, Weasel, Informer, Squealer, Backstabber, Double-Crosser, Agent-Provocateur, Shill, Judas, Quisling, Treasonist… In this week’s eSkeptic, Frederick V. Malmstrom and David Mullin explain why whistleblowing is a dangerous game. This article appeared in Skeptic magazine issue 19.1 (2014).

Share this article with friends online.

Subscribe | Donate | Watch Lectures | Shop

Why Whistleblowing Doesn’t Work:

Loyalty is a Whole Lot Easier

to Enforce than Honesty

by Frederick V. Malmstrom and David Mullin

Whistleblowing is a dangerous game. Most often, whistleblowers’ allegations are ignored or their motives are suspected, while whistleblowers themselves are attacked, ostracized, threatened, and even fired. The primary reason for whistleblowers failing to report dishonesty is fear of retribution, while conscience and duty are discounted. Wouldbe whistleblowers often rationalize their failure to blow the whistle because they fear they will be seen as disloyal. The dilemma between honesty and loyalty is presented as an instance of a Nash Equilibrium economic model. Toleration of dishonesty by others is the major contributing factor to both individual and organizational dishonesty, as clearly shown by past major scandals such as those uncovered in the New York City Police Department, Enron, the Tour de France, and the school systems of Atlanta, New Orleans, and the District of Columbia. More significantly, our research shows a steady rise in toleration of dishonesty at the three major U.S. service academies over the past half-century.

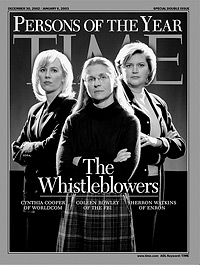

Figure 1: Time magazine’s 2002 Persons of the Year: Cynthia Cooper, Coleen Rowley, and Sherron Watkins. Printed with permission of Time Inc.

Whistleblowers as Heroes

On December 30th, 2002, Time magazine proudly introduced the world to its annual recognition, “Persons of the Year. The Whistleblowers.” The magazine cover displayed three determined-looking women, Cynthia Cooper of World-Com, Coleen Rowley of the FBI, and Sherron Watkins of Enron. These women were prominently identified and displayed as whistleblowers on organizational corruption. Initially, each of these women had informed their organization’s executives about the organization’s suspect practices. And in each case their warnings were ignored or stonewalled, either intentionally or otherwise. Cooper, Rowley, and Watkins had become unintentional whistleblowers only after their repeated warnings had been leaked to outside authorities and the press.1

Time enthusiastically praised Cooper, Rowley, and Watkins as highly moral heroes and pathfinders who might someday lead a revolution in organizational ethics. But, alas, the revolution never happened. Worse, neither Watkins nor Cooper were ever hired again, and Rowley was never promoted. Watkins and Cooper did later manage to start their own small private consulting firms, but the FBI silently retired Rowley. From time to time, all three of these whistleblowers are requested to speak to groups, but that’s about as far as the revolution has ever moved.

A Most Dangerous Game

Whistleblowing historically has been a dangerous and unequal contest, matching the individual against his or her own organization. Very few whistleblowers emerge from this contest without severe wounds, while the organization most often stands supreme. There have been few controlled or field studies on whistleblowing, and most published literature on this topic has been in the form of case studies, which have concluded that more often than not the whistleblower is counterattacked and often fired.2 Whistleblowing cases have been known to drag on for over 20 years, leaving the whistleblower with nothing to show but debts, and often unemployment. The majority of whistleblowers interviewed admitted they were initially naïve and had learned a painful lesson—never do it again.3

Contrary to popular fiction, whistleblowers are not held in high regard. “Whistleblower” is a word invented in the late 20th century and it’s often associated with unflattering pejoratives such as: Tattletale, Ratfink, Stool Pigeon, Snitch, Informer, Canary, Turncoat, Bigmouth, Busybody, Fat Mouth, Weasel, Informer, Squealer, Backstabber, Double-Crosser, Agent-Provocateur, Shill, Judas, Quisling, Treasonist, and so forth. There are at least as many synonyms for “whistle-blower” as Mark Twain identified for “intoxicated.”

The Tragic Hero: Breaking the NYPD’s Blue Code of Silence

One generalization from our research is that the closer knit the group, the greater the retribution on whistleblowers. Accordingly, few persons are as disliked by cops as a cop who becomes an internal rat. David Durk began as a New York City patrolman in 1963 and within seven years had worked his way up to the rank of detective. Working frequently with another legendary law-enforcement figure—New York City detective Frank Serpico—in 1971 they exposed cases of internal police corruption to the New York Times reporter David Burnham. Serpico later received recognition as a hero in the classic Al Pacino-Sidney Lumet film Serpico. Perhaps unfairly, the film ignored Durk’s equally important contribution to the investigations. Much of the corruption that Durk and Serpico exposed was of the run-of-the-mill variety, such as minor payoffs. However, Durk’s independent investigations opened up much more serious charges, such as cops who were running drug rings, organizing shakedowns, and even condoning murders-for-hire.

More importantly, Durk was one of the first to lay out the ubiquitous problem of departmental toleration. The biggest problem, according to Durk, was not with the dirty cops but with the dirty supervisors who had received information about corruption and sat on it or buried it. Durk was one of the very few who lived up to his sworn oath that New York policemen were on duty 24 hours a day, in uniform or out.4

Shortly after the investigation had run its course, Frank Serpico—by then a heartily disillusioned man—retired from the NYPD on medical disability from gunshot wounds incurred during a drug raid. However, David Durk stayed on, which he later regretted doing. During his remaining years with the NYPD, Durk received countless anonymous threatening letters, phone calls, and the usual dead animals (especially rats) deposited on his car and in his locker. He never advanced above the rank of lieutenant.

After 22 years of civil service, Durk retired in 1985 on a pension of less than $17,000 per year. Only then did he realize that he couldn’t get another job. He had unquestionably given New York City far more than it had ever returned to him, but job lead after promising job lead evaporated. Former associates and supervisors described Durk not as a civic whistleblower but as a “malcontent,” a “tub-thumper,” “a walking embarrassment,” and, of course, that popular pejorative, “crazy.” Here was his personal confirmation of the “nuts and sluts” defense. Regardless of the merits of the case, the accused’s lawyers will always attack either the integrity or the mental stability of a whistleblowing malcontent.

Durk eventually resigned himself to acting as a mostly unofficial, nonpaid consultant—and a valuable one too—but only to other persecuted whistleblowers. Like most of the ranks of whistleblowers, Durk never wrote a book, never ran for public office, and never profited financially from his efforts.5 And so ended another instance of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s postulate, “Show me a hero, and I will write you a tragedy.”

Dereliction of Duty

Legally, in most states ordinary citizens are under no obligation to report a crime or misdeed. However, public officials under oath operate under a different set of rules. Under United States laws, dereliction of duty (sometimes legally known as misprision of felony) can be committed by an officeholder who takes an oath of allegiance to the city, state, or nation. The official—whether police officer or president—commits a crime or misdemeanor when he conceals or intentionally does not report crimes and misdemeanors.

No one will ever know how many cases occur of superiors who pooh-pooh or cover up reports from would-be whistleblowers. Note this quote from the November 13, 2012, New York Times obituary of David Durk: “As Mr. Durk recalled, ‘The fact is that almost wherever we turned in the Police Department, wherever we turned in the city administration, and almost wherever we went in the rest of the city, we were met not with cooperation, not with appreciation, not with an eagerness to seek out the truth, but with suspicion and hostility and laziness and inattention, and with our fear that at any moment our efforts might be betrayed.’”6

From Enron to Atlanta Schools: A Nash Equilibrium at Work

There are plenty of individual case studies on whistleblowing, but, alas, there have been few reliable, controlled studies. Hundreds of insiders knew first-hand about the 1971 NYPD corruption. Scores of insiders knew about the Enron pyramid schemes of the late 1990s. Even more insiders knew about the recent teachers’ cheating scandals of Atlanta, New Orleans, and the District of Columbia, wherein platoons of teachers and administrators were illegally changing student test scores to meet the ever-increasing and unrealistic demands of the No Child Left Behind law.7 Those few unfortunates who reported misconduct of colleagues to their supervisors were ignored, disciplined, or fired. And so the result was that nobody did anything, and misconduct kept building. How could this have happened?

There is a struggle between whistleblowers and the rest of us who merely tolerate wrongdoing. This ongoing struggle is beautifully summed up within the powerful mathematical algorithm developed by the Nobel Laureate John Nash, now known as the Nash Equilibrium. In an investigation for Scientific American, Michael Shermer presented the doping scandals in cycling of the past few decades in the form of an economic game called The Prisoner’s Dilemma, in which players are presented with an option to either cooperate with a fellow prisoner or defect, the outcome of which depends on what the other prisoner does.8 We need not worry ourselves about the specifics of this particular game, but, in fact, the Prisoner’s Dilemma is but one variant of the Nash Equilibrium. In addition to the Prisoner’s Dilemma, a very short list of examples of other game variants of the Nash equilibrium include: (1) the Tragedy of the Commons, (2) Chicken, (3) the Dictator Game, (4) the Ultimatum Game, (5) the Battle of the Sexes, and (6) Mutual Assured Destruction.

Stated plainly, the Nash Equilibrium says no matter which way any player moves from his present position, he will be worse off than if he stands pat. That is, a system or contest is in equilibrium if neither player has anything to gain by changing strategies. There is no such thing as a final, satisfactory solution to the dilemma.9 All variants of the Nash Equilibrium deal with the contest of cooperation versus defection. That is, those persons who act in the best interest of their group are labeled cooperators, and those who act in their own selfish interest are labeled defectors.

A Formula for Mutual Disaster

Figure 2. Actor Peter Sellers as Dr. Strangelove. The Mutual Assured Destruction game played to its ultimate ghastly conclusion of thermonuclear war. Printed with permission of Sony Pictures.

The Cold War strategy of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) was the case in which neither the U.S. nor the USSR had anything to gain by launching a nuclear first strike because the other side could still retaliate and thereby assure mutual destruction of both countries. A MAD game assumes both parties will act reasonably and refrain from defecting, but this becomes a dangerous assumption if at least one party turns out to be irrational (e.g., a religious fanatic who looks forward to a martyr’s death). If defecting is the dominant strategy for both parties—as pointed out by Nobel economist Alvin Roth—the game becomes a most uncomfortable sub-optimal Nash Equilibrium, and both parties will then be worse off than if they had initially cooperated.10 The dominant strategy of mutual defection during a Mutual Assured Destruction contest was brilliantly played out to its ultimate ghastly conclusion of thermonuclear war in the 1964 black comedy film, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.11

The Whys and Why Nots of Whistleblowing

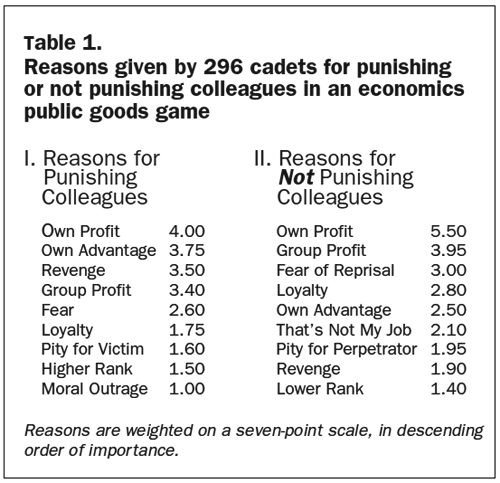

We explored the mechanics of whistleblowing with a public goods game at the U.S. Air Force Academy. In 2011, we conducted a large-scale experiment with 296 cadets enrolled in an economics course. Players were divided into teams of eight, with an initial cash stake given to each person. The individuals played in plain sight of each other with their military rank clearly visible. They had three options for donating or not donating cash to a communal pot. If the individual (1) chose to donate (Cooperator), the group would benefit, and the individual would share equally with his teammates. However, (2) if he chose not to donate (Defector), he could free-ride and keep his initial stake and also share in the group profits. The final wrinkle was that he could also (3) punish fellow freeriding team members (Whistleblower) by first paying an up-front fee and then fining the freerider who didn’t contribute to the general welfare. Our players had no special duty to either punish or not punish colleagues.

Surprisingly, our experiment yielded interesting findings as to why the players both did and did not punish their free-riding colleagues. The various reasons are listed in Table 1 on a seven-point scale, with seven as the highest priority, and one as the lowest. This table shows the mean values for all reasons listed in descending order of importance.12

The first conclusion that emerges from Table 1 is that people blow the whistle for a variety of reasons. The second conclusion is that most of the reasons—pro and con—for punishing colleagues are rather personal. That is, players will punish for primarily selfish reasons, such as personal profit and revenge. Fear of reprisal is weightier than loyalty. Players will, indeed, punish non-contributors for the welfare of the group, but that appears to be a secondary motive. Finally, the motive of Moral Outrage (conscience) is completely discounted.

Athletics, Doping, and Conscience

Conscience may well be a motivator for whistleblowing, but it appears to be a weak one. Michael Shermer cited three-time Tour de France cycling champion Greg LeMond, who had encouraged his fellow American, the 2006 Tour de France winner Floyd Landis, to come clean about his doping. “‘What would I gain doing that?’ LeMond recalled Landis saying. ‘You would clear your conscience and help save cycling.’ LeMond replied.” It took Landis three years to attend to his conscience and come clean, reporting both his own doping and that of his trainers and teammates, particularly his world-renowned, now disgraced, cycling teammate Lance Armstrong.13

The Whistleblower’s Dilemma: Omertà v. Duty

The decision to blow the whistle or not is often couched in the uncomfortable choice between loyalty and duty. Duty has been framed more politely by social psychologist Adam Waytz and his colleagues as a political contest of social fairness versus loyalty.14 Our research suggests, to the contrary, that the loyalty claimed by non-whistleblowers is more often a post-hoc, after the-fact justification rather than a sincere sentiment. Indeed, passionate vows of loyalty often run quite shallow.15

Among the most common reasons for not whistleblowing is the infamous Omertà rule, a peculiar code of honor dating back at least 500 years and probably as old as humanity. It translates to the Code of Silence whereby everyone maintains firm loyalty to the group, and no one within that group cooperates with authorities. Stated otherwise, it reads: You will not snitch. Defectors who break the code of silence are subject to extreme sanctions, including death. Reputed underworld figure Whitey Bolger, during his recently concluded criminal trial, had emphatically argued that snitching on fellow mobsters is a far worse crime than murder.16

Group loyalty is often claimed by group members as a prime motivator for not whistleblowing, but our research suggests that this excuse is largely a dodge. More likely, it is the fear of retribution that stifles whistleblowing. Thus, there is a corollary to the Omertà rule: Loyalty is a whole lot easier to enforce than honesty.

The Academies’ Honor Codes and the Duty to Blow the Whistle

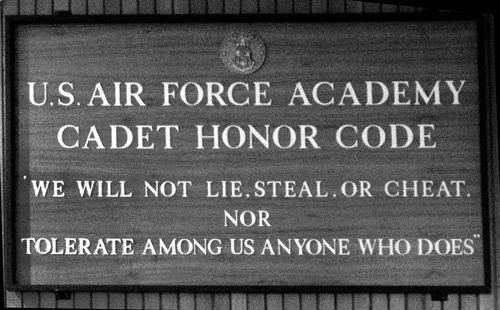

Figure 3: The U.S. Air Force Academy Cadet Honor Code. The bottom three lines state the non-toleration clause.

All U.S. service academies have an honor code that clearly mandates that cadets and midshipmen will not lie, cheat, or steal. The U.S. Air Force Academy’s honor code reads specifically, “We will not lie, steal, or cheat, nor tolerate among us anyone who does.” That final phrase of the honor code is traditionally referred to as the “non-toleration clause.”17 The U.S. Military Academy’s honor code is similar. The U.S. Naval Academy’s honor code differs only in that toleration of dishonesty is viewed as a disciplinary matter and not one of honor. Either way, it is a cadet’s and midshipman’s sworn duty to report dishonesty; not to do so is dereliction of duty. Lying, cheating, and stealing—and, of course, tolerating lying, cheating and stealing—at any service academy can be officially met with severe sanctions, including probation, disenrollment, or outright dismissal.

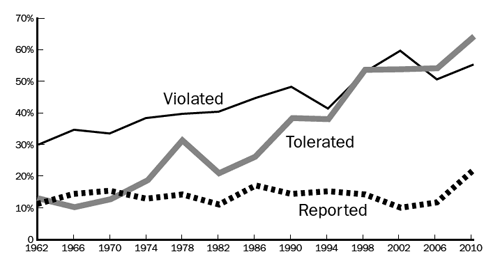

Figure 4: 52-year trends of self-admitted violations, reporting of violations (whistleblowing), and toleration of honor violations by 2,465 U.S. service academy graduates. Toleration of dishonesty has been steadily increasing over the past half-century.

In particular, we found the role played by deliberate toleration of fellow cadets and midshipmen engaging in unethical or dishonest acts was a highly significant factor leading to even further widespread dishonesty. Our 30-year ongoing survey effort of a longitudinal random sample of 747 Air Force Academy resignees18 and 2,465 graduates of the three major U.S. service academies from 1959 through 201119 clearly showed a significantly steady rise in self-admitted honor code violations from about 10% to over 50%.20 Most disturbingly, about 15% of our respondents had apparently personally re-interpreted their institutional honor codes and somehow no longer regarded toleration of dishonesty by others to be a violation of their duty to report.21 This is a rear-exit way of excusing your sin by arguing, essentially, That one didn’t count.

The Service Academies and Toleration of Dishonesty

By 2010 the effective rate of admitted toleration of dishonesty by graduates of all three major U.S. service academies (Army, Navy, and Air Force) violations had risen to 65%. What’s more, for the first time the rate of toleration of dishonesty had outstripped the rate of self-admitted honor violations, 65% to 55%. This is in clear contradiction of their honor oath, for large numbers of cadets and midshipmen no longer consider toleration of dishonesty as dereliction of duty.

Toleration of dishonesty seems to be an especially sticky problem at all three major U.S. service academies, and our calculations also show toleration quickly leads to cynicism. Results from a longterm survey returned from 2,465 service academy graduates from the classes of 1959 through 2010 showed that toleration of dishonesty is by far the strongest predictor of personal dishonesty, accounting for a whopping 50% of variance. Toleration is equally predicted by the following factors: (1) Lack of respect for the honor codes, (2) Lack of resolve (lack of courage) to either report or confront others’ dishonesty, and (3) Subsequent lying, cheating, and stealing by the academy graduates. In other words, personal toleration of dishonesty almost inevitably led to cynicism.22

The results of these studies strongly support our hypothesis that toleration of dishonesty by others is the most prevalent element within—if not the key to—understanding dishonest behaviors. The non-toleration clause of the cadet Honor Code, while certainly a worthy ideal, appears to have had only weak-to-no effectiveness in curtailing dishonesty. One compelling explanation behind the ineffectiveness of non-toleration is that there are obviously heavy penalties but few rewards for whistleblowing. The whistleblower who acts out of pure motives of conscience is a rare saint indeed. For most people there is simply no incentive to move off their Nash Equilibrium.

Wanted: Good Whistleblowing Research

If toleration of dishonesty exists on such a significantly measurable scale in a cohesive, formal organization such as a U.S. service academy with its rigidly defined honor code, we are left to speculate on the prevalence of toleration in a less-regulated civilian society. Legislation is not a satisfactory answer. Unfortunately, there is little to no research on the welldocumented ineffectiveness of such well-meaning federal measures as the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Law and the 1989 Whistleblower Protection Act.

As of 2007, only 3 of 203 suits brought before federal jurisdiction under the Federal Whistleblower Protection Act were successful. (What’s more, the CIA and FBI have exempted themselves from the law.) As for the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, only 1.8% of the whistleblowing cases were found to have merit, and 70% of the cases were dismissed outright. It is evident that enforcement of such laws is hindered by lack of incentives and severe penalties to the whistleblower.23

More recently, the issue of widespread NYPD police misconduct has resurfaced in the form of massive violations of the stop-and-frisk laws. Whistleblowers are again disciplined, and the organization stands in pious denial. An April 28, 2013, column from the Washington Post concludes with a memorable observation from a former whistleblower: “‘Nothing’s changed,’ the 76-year-old [Frank] Serpico said in a recent phone interview when asked about the current crop of whistle-blowers. ‘It’s the same old crap—kill the messenger.’”24 ![]()

References

- Time Magazine. 2002. “Persons of the Year: The Whistleblowers.” December 30.

- Micelli. M., Near, J. & Schwenk, C., 1991. “Who Blows the Whistle and Why?” Industrial and Labor Relations, 45, 113–130.

- Alford, C.F., 2001. Whistle-Blowers, Broken Lives and Organizational Power. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- McFadden, R. D. 2012. “David Durk, Serpico’s Ally Against Graft, Dies at 77.” The New York Times, November 12.

- Lardner, J., 1996. Crusader. The Hell-Raising Career of Detective David Durk. New York: Random House.

- McFadden, Robert, 2012.

- Winerip, M. 2011. “Cracking a System in Which Test Scores Were for Changing.” The New York Times, July 17.

- Shermer, M. 2010. “The Nash Equilibrium, the Omertà rule, and Doping in Cycling.” July 7.

- Fisher, L. 2008. Rock, Paper, Scissors: Game Theory in Everyday Life. New York: Basic Books.

- Kagel, J. & Roth, A. E. (Editors). 1995. The Handbook of Experimental Economics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. 1964. Film: Columbia Pictures.

- Carson, K.R. et al. 2011. “Whistle-blowing and rank structure in a volunteer contribution mechanism game.” Paper presented to the Western Economic Association International; San Diego, CA, June 30.

- Shermer, 2010.

- Waytz, A., Dungan, J. & Young, L., 2013, in press. “The Whistleblower Dilemma and the Fairness-Loyalty Tradeoff.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

- Malmstrom, F., 2011. “The problems with whistle-blowing: U.S. v. Wailly.” Journal of Psychological Issues in Organizational Culture, 2(2), 96–107.

- Seelye, Katherine G. 2013. “As Bulger Trial Opens, Code of Honor is Subtext.” The New York Times, June 11.

- Air Force Cadet Wing Honor Code Reference Handbook, Vol I. Honorable Living, October, 2009. U.S. Air Force Academy CO: Center for Character Development.

- Malmstrom, F. & Mullin, R.D., 2013. “Dishonesty and Cheating in a Federal Service Academy: Toleration is the Main Ingredient.” Research in Higher Education Journal, 19, 120–137.

- The survey is available in the appendix of: Carrell, S.C., Malmstrom, F. & West, J. 2008. “Peer Effects in Academic Cheating.” Journal of Human Resources, 43(1), 173–207.

- Malmstrom, F. & Mullin, D. 2013. “The Long-Term Decline of Service Academy Honor Codes.” Paper presented to the Rocky Mountain Psychological Association, Denver, CO, April 12.

- Mullin, D. & Malmstrom, F. 2013. “Service Academy Honor Systems: A Half-Century of Decline.” Paper presented to the Western Economic Association International, Seattle, WA, June 29.

- Mullin, D. & Malmstrom, F., 2013.

- Dworkin, T.M., 2007. “SOX and Whistleblowing.” Michigan Law Review, 105(8), 1575–1580.

- The Washington Post. 2013. “Whistleblowers Say They’re Harassed for Exposing Stopand-Frisk Wrongs; 2 Testify at Trial,” April 23.