About this week’s eSkeptic

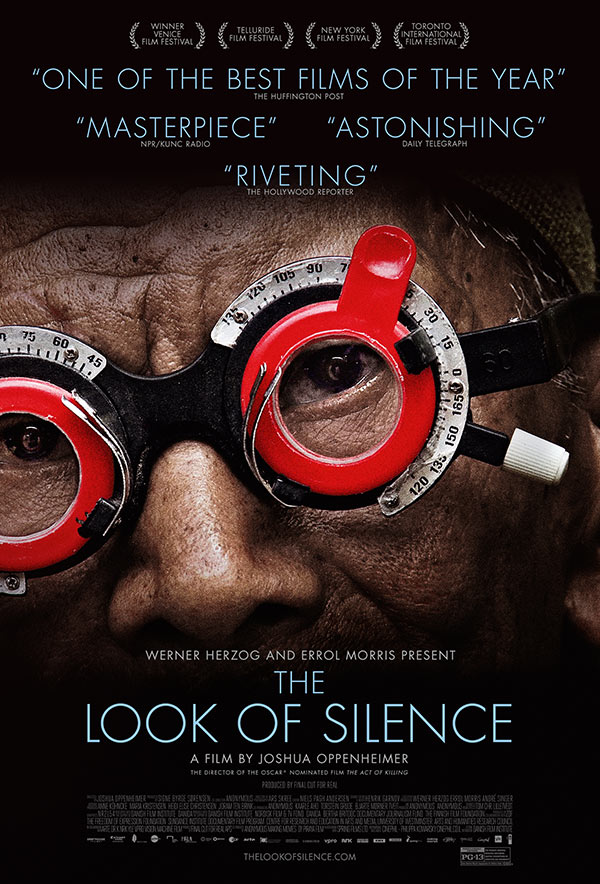

In this week’s eSkeptic, Stephen Beckner reviews Joshua Oppenheimer’s documentary film The Look of Silence, produced by Signe Byrge, Executive Producers Werner Herzog, Errol Morris, Andre Singer Sørensen, Presented by Drafthouse Films, Participant Media, and Final Cut For Real, 103 minutes. The above image is a still from the film.

Stephen Beckner is a screenwriter and filmmaker. He is best known for his feature film A.K.A. Birdseye. He is currently developing a feature film project based on the American militia movement of the early 1990s. In addition to his work in film, he has collaborated on video games, notably as head writer for the award-winning multi-platform adventure game Perils of Man.

Anatomy of a (Mass) Murder

by Stephen Beckner

Let sleeping dogs lie, the old saw goes, but judging from his latest documentary, writer/director Joshua Oppenheimer doesn’t subscribe to that particular bit of folk wisdom. No, for all its impartial probing and careful emotional inquisitiveness, The Look of Silence aims to stir things up. In fact, it wants to raise the dead.

Like its companion piece, the 2012 Academy Award nominated The Act of Killing, Oppenheimer’s subject is Indonesia’s anti-communist purge, a frenzy of violence and butchery at the hands of vigilante youths cum organized death squads. Between 1965 and 1966, with the explicit consent of the Indonesian military, anyone suspected of being a communist, harboring communist sympathies, or in some cases just knowing a suspected communist, was rounded up and delivered to busy backrooms that functioned as human clearing houses, where zealous young men—many of them gangsters before the Suharto regime found a suitable use for their dubious skillsets—saw it as their duty to beat, stab, and/or garrote the evil offenders. Corpses were then rendered into mass graves, or heaved into local rivers under cover of darkness. For years, the scale of the mass killings was not known to the outside world, but is now estimated at more than a million dead. Fifty years on, there has been no moral or legal reckoning—the killings are still missing from Indonesia’s official history, though the killers themselves live as heroes amongst their fellow citizens, revered by some, feared by many.

As topics for documentary go, political pogroms are nothing new, but then Oppenheimer’s films are not political. What sets these documentaries apart, and what makes them of particular interest to skeptics, is Oppenheimer’s analytical approach to his subject. His characters are not players in service to a political argument so much as psychological test subjects. In The Act of Killing, Oppenheimer treats his participants—former killers all—with a clinician’s emotional distance. We watch in astonishment as the now-aging men are given a grant to confront their violent pasts by making personal films ostensibly reenacting their “heroic” deeds, and proceed to lose themselves like mice in a laboratory maze of their own making.

The principal figure of the film, Anwar Congo, casts himself as a noir gangster, and demonstrates the evolution of his killing techniques as demand for his services increased. But when he briefly steps into the role of one of his victims, the look in his eyes changes, his psychological armor slips away. Oppenheimer’s steadfast refusal to judge the participants increases their trust in the process and in turn they make themselves more emotionally available. What emerges is at a once a rending human tragedy, and a forensic debriefing on the mechanics of guilt and the psychological contortions men put themselves through to avoid it. Oppenheimer’s camera works like a scalpel, cutting through the layers of rationalizations to expose the underlying psychological anatomy of…not killers, but of ordinary men who became killers, and who have tried in vain for five decades to become ordinary men again.

When Hannah Arendt was covering the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann for The New Yorker, she famously employed the phrase “banality of evil” to underscore Eichmann’s ordinariness. The context of Eichmann’s trial was personal guilt for a state-sponsored crime. The crime itself was never in doubt. But in Indonesia the evil prevailed, the orchestrators of their genocide were never brought to justice, and no crime was ever acknowledged. As a consequence, the banality of evil is on full display, and The Look of Silence gives us the opportunity to witness it up close. Here Oppenheimer shifts the point of view from the perpetrators to the survivors, focusing on the family of Ramli, one of the rare victims whose murder was witnessed and whose remains rest in a marked grave near the Snake River. Because of this, Ramli has come to represent all the victims. His brother Adi, born a year after Ramli’s death, sets out to meet the killers, who openly boast about the unspeakably brutal execution. One of the men, concerned that his place in history may be overlooked, has even self published a memoir with hand drawn illustrations depicting the night’s gruesome proceedings.

Meeting Adi was fortuitous for Oppenheimer, who understood early on that his strength of character and remarkable composure under pressure made him the ideal person to conduct these encounters. A practicing optometrist, Adi visits the killers under the guise of checking their eyes. As he edges closer to the subject of his brother, he never allows anger or resentment to dominate the conversations, even when he has every right to do so. Instead, it is Adi’s abiding sadness that prevails. More than anything, he simply wants to make sense of it all. But inevitably, when the men learn that Adi is the brother of Ramli, their stories change. We see their minds suddenly racing to rationalize their behavior. They were merely agents of the state, they say, acting for the greater good, purging a societal evil, etc. In the psychological denuding that ensues, even their boasting is revealed as a coping mechanism to assuage their guilt. And should all these fail, threats to Adi and his family serve to shift the blame.

In perhaps the most vivid example of the lengths to which these men went to avoid moral culpability, many claimed that it was common practice for the killers to drink the blood of their victims. Failing to do so resulted in certain madness, they averred, and those who abstained from the vampiric ritual were avoided or shunned. As shocking as these confessions are, the film never surrenders to its most lurid details. Oppenheimer’s gaze remains detached, constantly seeking out broader, and ultimately scarier moral implications. We are reminded that silence has its price. If you let sleeping dogs lie, then lie they will. They will lie mostly to themselves at first, but eventually the lies will proliferate.

For some in the skeptical community, there’s a certain morbid satisfaction to be derived from seeing individual cognitive biases so incisively exposed. But any temptation to rubberneck quickly fades when those biases are blatantly enlisted on a societal scale by the state in the service of death. In a telling NBC news report from that time, one Indonesian official claims that many of the communists came forward and asked to be killed—an invocation of the notion of atonement that slyly connects communism with religious sin. Many death squad members later claimed that they knew their victims were communists because they didn’t pray. This convenient narrative equating godlessness with communism has now been institutionalized in Indonesia by a federal blasphemy law aimed not only at making atheism a capital offense, but also at rationalizing the current regime’s murderous origins.

For all its forensic power, The Look of Silence remains a deeply compassionate film. It is provocative, but what it’s trying to provoke finally, is understanding. The titular silence is a closed door that prevents that understanding, trapping perpetrator and survivor alike. Crucially, Oppenheimer never gives us the easy out of dehumanizing the killers. They are not depicted as creatures apart, monsters stalking the wrong side of some unseen but impenetrable moral barrier. No, they are ordinary men, banal men, who became killers in a specifically identifiable way. This viewer could not escape the chilling conclusion that we are, all of us, only a couple of rationalizations away from the killer inside. It’s easy to find him—heartbreakingly, terrifyingly easy. ![]()