We acknowledge the death of one of the giants of 20th and 21st century science, Edward O. Wilson, the entomologist, evolutionary theorist, and unifier of all knowledge. Many obits that include the details of his stellar career and engaging life have already been published in most media outlets, so here we reprint an extensive and intimate interview we published in Skeptic in 1998, Vol. 6, No. 1, conducted by our editor Frank Miele, upon the occasion at the time of the publication of Wilson’s game-changing book Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, which extended the Enlightenment belief that through science and reason humans can understand all aspects of the world — physical, biological, social, and even moral. The book inspired Skeptic Publisher Michael Shermer to write The Science of Good and Evil and The Moral Arc to see how far into the realm of morality and ethical theory science and reason can take us. Is this a realistic goal? Read Wilson’s thoughts on the matter in this illuminating conversation.

Edward Osborne Wilson has had more impact on the borderland between the natural and the social sciences than anyone alive, possibly anyone since Charles Darwin. Perhaps that is why so astute an observer of the interrelationships between science and culture in contemporary America as Tom Wolfe, best-selling author of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Painted Word, The Right Stuff, and Bonfire of the Vanities, has dubbed Wilson “Darwin II,” the intellectual guide not to “the evolution of the species…but to the nature of our own precious inner selves” (Wolfe, 1996, 214). Pellegrino University Research Professor and Honorary Curator in Entomology of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University, Wilson is a member of the National Academy of Sciences, recipient of the Swedish Academy’s 1990 Crafoord Prize (the world’s most distinguished environmental biology award), the International Prize for Biology from Japan (1993), and the world’s leading expert on ants. He is also co-originator of the theory of island biogeography, a champion of preserving the rain forests and biodiversity (for which he has received the 1990 Gold Medal of the Worldwide Fund for Nature and the 1995 Audubon Medal of the National Audubon Society), and winner of two Pulitzer prizes in general non-fiction for On Human Nature (1978) and The Ants (1990), the latter along with co-author Bert Hölldobler.

Edward Osborne Wilson (1929–2021)

Wilson’s book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (1975) laid out the evidence for the evolutionary and genetic basis of social behavior across the animal kingdom. The fact that he dared to include a final chapter, “Man: From Sociobiology to Sociology,” set off the Sociobiology Wars of the late 1970s. That conflict was fought not only in academic journals and at conferences, but in campus protests and demonstrations. At a special symposium on sociobiology at the 1978 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), a member of the International Committee Against Racism (INCAR) dumped a pitcher of water on Wilson’s head as she and fellow demonstrators chanted, “Wilson, you’re all wet!” Skeptic Editorial Advisory Board member Stephen Jay Gould chastised the crowd by quoting Lenin on the inappropriateness of violence for mere radical posturing, as opposed to the attainment of worthy political goals, and referred to the incident, again in Lenin’s words, as “an infantile disorder of socialism.” Skeptic Editorial Advisory Board member Napoleon Chagnon tried to make his way to the podium to eject the protesters (Wilson, 1994, 348–350).

While his views on human nature have been anathema to many self-identified leftists, Wilson’s passionate pleas on behalf of preserving the rain forests and on the value of biodiversity have often been criticized by many on the political right. Julian Simon, the late pro-growth economist, praised Wilson as a “superb scientist,” but questioned the estimates of the increasing rates of animal extinctions that Wilson has cited in defense of environmental preservation (Miele, 1997). And in one of his zanier zingers, even for him, conservative radio talk show host Rush Limbaugh denounced Wilson’s article “Is Humanity Suicidal?” in the New York Times magazine (1993), as the ranting of a “radical liberal environmentalist who teaches at Harvard,” and who is “just the kind of guy the Clinton administration listens to and who is teaching our children” (Limbaugh, 1993). This must have come as news not only to Wilson and the Clinton administration, but all those left-wing demonstrators at Harvard.

The model of a kind and gentlemanly scholar, now nearing 70, Wilson has the ability both to ignite intellectual arguments that draw common fire from otherwise bitter enemies, and also to inspire affection and admiration from most of those who disagree vehemently with him, and all of those who know him personally. His latest book, Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (Knopf, 1998), has set off yet another conflagration in the intellectual and academic journals and conferences and their associated e-mail networks.

In Consilience, Wilson argues that the natural sciences, based as they are on extensions of Darwin’s seminal vision, have now reached a state of sufficient maturity that they can light the way through the borderlands connecting those disciplines with not only the social sciences, but also religion, ethics, politics, and the arts and humanities. The idea of basing anything on evolution is anathema to some, and the biologizing of social science sets off an immediate protest by others. Not only religious and political zealots, but contemporary philosophers like Richard Rorty and Skeptic icons like Stephen Jay Gould, the late Carl Sagan, and Michael Shermer, question not only our ability, but the desirability of trying to unite such traditionally discrete domains as science and religion. To Wilson, eschewing consilience in favor of maintaining epistemological boundaries between the disciplines has produced a result analogous to fragmentation in a computer system, in which the scattering of files over non-contiguous areas of memory increasingly degrades performance until it eventually brings the system to its knees. In its place Wilson calls for an instauration, a term coined by Sir Francis Bacon (one of the heroes of Consilience), meaning “a new beginning” (1998, p. 27), of the dream of the pre-Socratic Greek philosophers, who walked the Ionian shores and searched for unity in the nature of all things. Consilience may well be the most influential book in setting an overall direction for contemporary intellectual thought since Karl Popper’s 1943 The Open Society and Its Enemies. Here is E. O. Wilson on Consilience and its Discontents.

Skeptic: In previous books (Wilson, 1975, 1984) you’ve given us the words Sociobiology and Biophilia. Consilience is not your word. Whose word is it, what does it mean, and why do you choose it as your title?

Wilson: The word was introduced in 1840 by William Whewell in his master work, The Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences. He used it to mean the interlocking of cause and effect explanations across disciplines. Whewell thought consilience provided the key to understanding the natural sciences as a whole; to use his words, to “proving the validity of theory,” by which he meant that theories which matched across disciplines, say chemistry and physics, or chemistry and biology, were consilient and therefore more likely to be true.

The word has been used sparingly since Whewell. I chose it because it has retained its purity, because of its rarity. The other words that might be used are “coherence” and “inter-connectedness,” but these much more common terms have many meanings, only one of which is the same as consilience. I hope that I can now introduce the word “consilience” into the mainstream to capture one of the key qualities of the scientific method.

Skeptic: It struck me as odd that you’d choose a word from Whewell, who, I believe, was an opponent of Darwinism (Ruse, 132).

Wilson: If that’s true, he didn’t know consilience when he saw it!

Skeptic: You also refer to the “Ionian Enchantment,” which you tell us physicist and historian Gerald Holton (1995, 4) defined as: “a belief in the unity of the sciences — a conviction, far deeper than a mere working proposition, that the world is orderly and can be explained by a small number of natural laws. Its roots [hence the name] go back to Thales of Miletus, in Ionia, in the sixth century BCE” (1998, p. 4).

I take this as an attempt on your part to get back to the founders of Western scientific philosophy — the pre-Socratic Greek philosophers. But elsewhere, you pay homage not only to your own upbringing as a Southern Baptist in Alabama, but also to the Biblical tradition which underlies Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, when you say that Chinese philosophy missed the scientific boat when it “abandoned the idea of a supreme being with personal and creative properties. No rational Author of Nature existed in their universe; consequently, the objects they meticulously described did not follow universal principles, but instead operated within particular rules followed by those entities in the cosmic order. In the absence of a compelling need for the notion of general laws — thoughts in the mind of God, so to speak — little or no search was made for them” (1998, 31).

Economist Kenneth Boulding (1984) has made a similar statement to the effect that by partitioning the world into the sacred and the profane, those traditions allowed for the growth of science, at least as it pertains to the profane. But isn’t there an alternative interpretation that not only the Biblical tradition, but Socratic and post-Socratic philosophy, instead constitute a gigantic wrong turn away from the Ionian Enchantment and from which we are only now grudgingly regaining momentum, and then only in circumscribed areas?

Wilson: The explanation of slowing of Chinese science we owe to Joseph Needham (1978), who is the principal Western authority on the subject. The point you make is very important. It appears to me that the Judaeo-Christian tradition worked both ways. On the one hand, as you say, it created a dualistic view of the universe that impeded the thought of even the best of the Enlightenment philosophers. Notice, for example, how Descartes probably created dualism in order to avoid clashing with the prevailing Christian theology of his time and therefore getting in serious trouble. Note how Newton believed that there were, in fact, two books to be read — the Book of Nature and the Book of God’s Word and that he actually spent time on both. He succeeded spectacularly on the first, and failed totally in the second.

On the other hand, there was the view that the world is orderly. In the minds of many of the pioneers of the scientific revolution, that reason was God. So the search for abstract laws seemed logical to them, which turned out to be a correct methodological assumption.

Skeptic: Isn’t there in the Biblical and the Socratic traditions an attempt to understand the world by seeking to explain not how things work scientifically, but rather what they mean moralistically? Doesn’t that temptation eventually lead us into deconstructionism?

Wilson: It certainly would if we were to ignore virtually everything we know about biology, including evolution. We now understand how organic systems, including our own brains and minds, were self-assembled, and how apparent purpose evolved as a property of the biological human brain. The latter was, of course, the triumph of Darwinian thought, which was perceived correctly well over a hundred years ago as the principal threat to the theological concept of a purposeful God.

Skeptic: You pay homage to the Enlightenment thinkers and tell readers that they basically got it right in their “vision of secular knowledge in the service of human rights and human progress,” which you consider to be “the West’s greatest contribution to civilization” (1998, 14). But wasn’t the Enlightenment yet another wrong turn, and one you have been very critical of, in its strong preference for environmentalist, nurturist explanations of human behavior, as opposed to hereditarian, naturist, or interactionist explanations? Shouldn’t you have drawn a distinction between the French Enlightenment, which I would argue is the godfather of Marxism, and what Paul Hollander (1988) has dubbed “the Adversary Culture” and the Scottish Enlightenment of David Hume, which was godfather to Adam Smith and later Charles Darwin and Sir Francis Galton?

Wilson: I couldn’t argue against that distinction. Whoever injected the virus of perfectibility, and I suppose that was indeed a French influence, certainly made the perversion of Enlightenment thought possible. I hope I spelled out in enough detail in Consilience the real risk of perfectibilist Enlightenment thought, thought that leads to the idea that there is one system of government, one method of systematic description that must rule and which can bring humanity to perfection. That’s certainly one of the most dangerous ideas of the 20th century.

Skeptic: But isn’t that exactly what your critics would say you’re trying to do in Consilience, and even earlier in Sociobiology?

Wilson: I don’t think I was ever accused of being perfectibilist.

Skeptic: No, but of having one viewpoint that everything gets folded into.

Wilson: If any critics try to put it that way, it would be a stretch. What I’ve done is to lay out not a system that could be translated into a perfect political or economic order, but quite the contrary, to provide a method for mapping the unknown with the aim of showing the connectedness across the principal domains of knowledge. I don’t think those are the same thing.

Skeptic: Let me go back to Needham and Chinese philosophy. You point out how China was ahead of Europe in technology and science between the first and 13th centuries, but then fell behind because Chinese philosophy focused on “the harmonious, hierarchical relationships of entities, from stars down to mountains and flowers and sand. In this world view the entities of Nature are inseparable and perpetually changing, not discrete and constant as perceived by the Enlightenment thinkers. As a result the Chinese never hit upon the entry point of abstraction and break-apart analytic research attained by European science in the seventeenth century” (1998, 30–31). Isn’t that exactly what the developing disciplines of chaos and complexity theory, the Santa Fe Institute, and “the butterfly flapping its wings” are all telling us we need to do so we can bring science into the next millennium? Or, in your opinion, is that stuff just so much nonsense?

Wilson: Oh no! First let me say that Chinese science made tremendous strides. It’s just that they slowed down because of their failure to emphasize reduction and abstract law. I don’t see the mathematical models and forms of reasoning associated with complexity and chaos theory as being Chinese at all in this sense. In fact, they are exquisitely Western and consilient in approach. For example, the best of chaos theory is an attempt to explain the extremely complex patterns in nature by a relatively small number of deterministic equations.

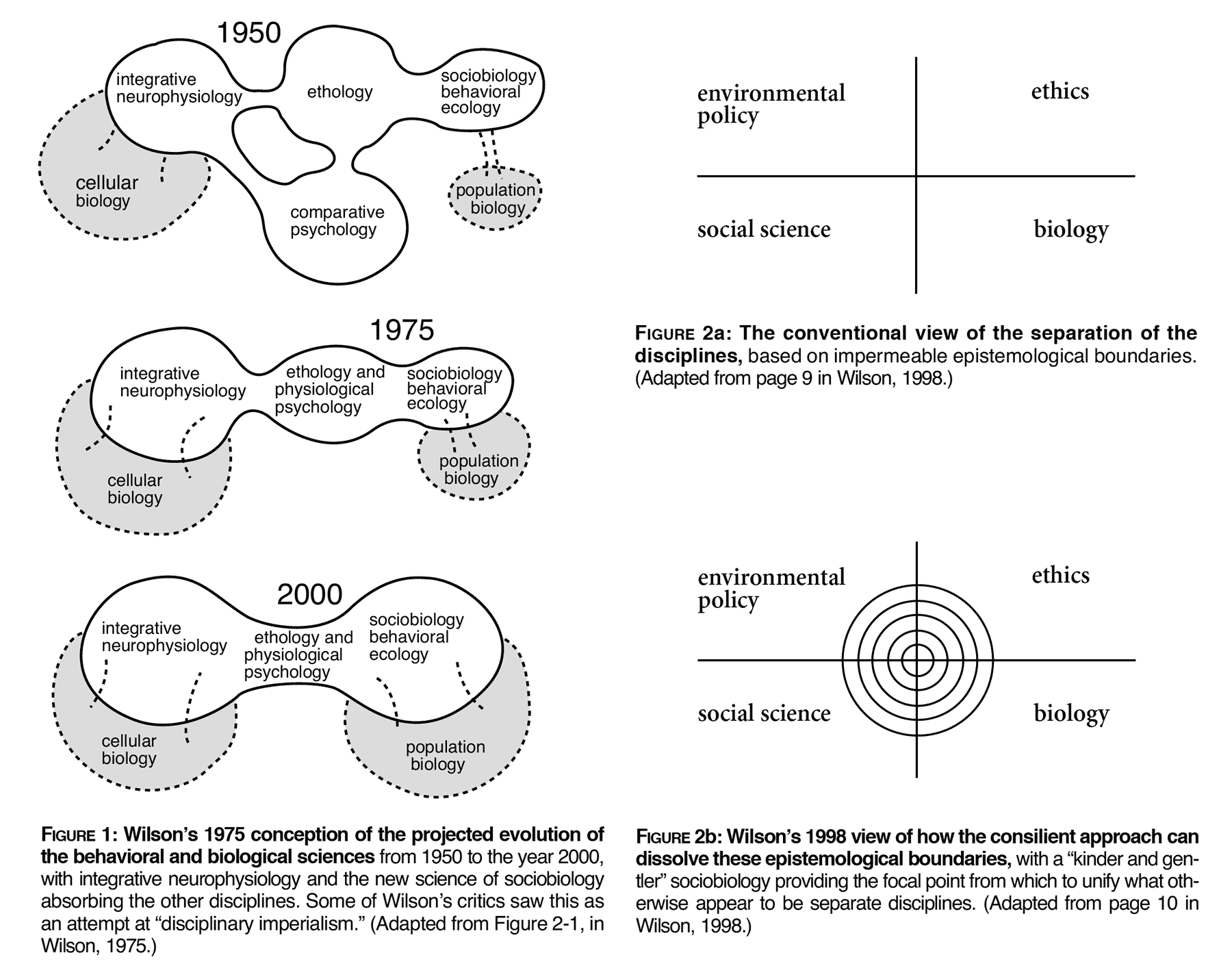

Skeptic: This brings me to the diagram on page 5 of Sociobiology in contrast to the ones on pages 9 and 10 of Consilience (See Figures 1, 2a and 2b above). Back in 1975 you were accused of preaching an amalgam of philosophical reductionism, genetic determinism, and an attempt at “disciplinary imperialism” (see Caplan, 1978; Takacs , 1996, and Wilson, 1994). Now in 1998, your discussing the unity of knowledge, including even art, literature, and religion. But I sense you’ve doing it from a perspective of, if not holism, at least emergence. A recent article in Science by Nigel Williams (1997) summarized the CIBA foundation symposium that provided a lengthy critique of reductionism, with protein folding being the principal case in point. So how has your view of reductionism versus holism changed? Is there a middle ground of emergence that allows us to explain things like protein folding? Or is emergence only a nice name we put on our ignorance?

Wilson: No, I think emergence is a name we put on patterns that cannot be easily explained by means of reconstruction from the elements revealed through reductionistic analysis. In theory, we should be able to predict many of the complex patterns at higher levels of organization, which we call emergent, from a knowledge of the constituent elements and their interactions. In most cases, especially when you get into biology, this would require massive computational capacity.

Unfortunately, emergence tends to come across as a mystical concept because going from a knowledge of the elements to predicting the complex interactive patterns is such a difficult step. It has been tempting for some thinkers to say that there are truly new phenomena that are independent of anything revealed by reductionistic analysis and that the connection between the constituent elements and the higher levels of organization cannot be made. I believe that when most scientists think it through, they would not accept that view. Scientists think all the time about complexity at whatever level they are investigating, the cell as a whole, or ecosystems as a whole. But at the same time, the most successful scientists proceed through reduction by analyzing that system into its constituent elements with the aim of reconstructing those elements back into an understanding of the complex whole.

As I pointed out in Consilience, the level of complexity of the re-synthesis from a pretty complete knowledge of the elements and how they interact up to protein synthesis is a slow process and it hasn’t been achieved yet. When it is we will have taken both reduction and synthesis to emergent levels, all the way from quantum physics to protein synthesis. Going beyond that to an organism, an ecosystem, or a mind may prove ultimately to be beyond our computational capacity, but it’s a worthy goal, the pursuit of which reflects the confidence we have gained in the consilient approach by its success in explaining less complex systems.

Skeptic: My question remains whether your dedication to reductionism is methodological, that it’s pragmatically the best way to go, or is it metaphysical, that eventually, with enough knowledge, everything can be encompassed within our understanding?

Wilson: Both. Methodologically, reductionism has proven spectacularly successful across a large part of science. Metaphysically, we are speaking again of the Ionian approach to the physical world.

Skeptic: On page 13 of Consilience you say that every college student, public intellectual, and political leader, should be able to answer the question, “What is the relationship between science and the humanities, and how is it important to human welfare?” This seems to be the very heart of what’s at issue in Consilience, why philosopher Richard Rorty (1998) criticized your thesis in the Wilson Quarterly, why your keynote speech at the 1996 meeting of Human Behavior and Evolution Society got a standing ovation, but then John Beckstrom of Northwestern University Law School felt moved to send a letter to fellow HBES members telling them you were flirting with the naturalistic fallacy. Another HBES member, psychologist Irwin Silverman (1993, 1998), has argued that the only defensible political role for the behavioral scientist is no role at all — science and politics must be treated as dichotomous and often antithetical domains. Well known skeptics like Stephen Jay Gould, the late Carl Sagan, and Michael Shermer have all argued for treating religion and science as, to use Gould’s neologism, NOMA — Non-Overlapping Magisteria. Can we unify knowledge through the consilient approach or should we compartmentalize knowledge and lead our lives as if we were split-brained? Isn’t that what these critics of consilience are asking us to do?

Wilson: A comment on the side, which you can print or not — Frank Miele you are well informed! That’s a compliment I can’t resist making.

Skeptic: I can’t resist taking it!

Wilson: These strong, even emotional objections that you cite are what I call the secular intellectuals’ white flag. It’s very comfortable at this point, and believe me, politically correct in an almost all-encompassing sense, to say that scientists should be humble and partition off their thinking about the physical world and religious phenomena. I believe no such thing. I just find religion one of the more interesting physical phenomena that we should be studying more vigorously.

Skeptic: Then let me toss you an even hotter potato. Wouldn’t even those who want us to treat science and politics as separate, non-overlapping realms have to acknowledge that every political philosophy, including their own, has at its core a theory of human nature, even if only to deny that there is such a thing?

Wilson: You’re exactly correct about that. This is the point I tried to make in Consilience in order to quiet forever the arguments against sociobiology by pointing out that everyone has a theory of human nature. (I know I won’t succeed, but I tried.) The so-called opposition to sociobiology — the argument that there is no human nature, which has been so widespread and emotionally argued — is actually a theory of human nature. It says that whether the human brain evolved or was put there by God, it was constructed in such a way that it is equally likely to absorb any form of information, belief system, or custom.

When you think about that for a while, it is highly unlikely. In fact, some investigators like Charles Lumsden and myself (1981, 1983) have shown that it is almost impossible if the brain originated by organic evolution. We now have enough evidence from sensory physiology and cognitive neuroscience to show why that view is untrue. There is a human nature, and among the varieties of theories of human nature, you must choose one. There is a system of what I call epigenetic rules, algorithms that predispose people to choose certain options as opposed to others. I find this feeling that political and religious belief are somehow insulated from explanation and from testing in terms of their etiology to be a curious product of late 20th-century thought that we will do better to get past.

Skeptic: Then let’s think about trying to build a political or religious system on a scientific basis. One of the defining characteristics of science, maybe the defining characteristic, is that it deals in corrigible, tentative statements. Yet we have this desire to ground our morals, our laws, in something eternal — or at least something we like to think is eternal. Suppose Thomas Jefferson had written, “I’m not really sure about all this, but based on the best evidence we have at the present, we cannot reject the null hypothesis that as far as the essential qualities necessary for citizenship, the differences between individuals, at least healthy adults, are insufficient to support any recognition of them as a principle of law.” Would anybody have picked up his gun and fought in the American Revolution?

Wilson: I rather doubt it. That would be a fine Declaration for MIT, I suppose. As I explain in Chapter 11 of Consilience, “Ethics and Religion,” I believe we have to choose between Transcendentalism, which in this context means that ethics are rooted in precepts that exist outside of humanity and are then acquired by humanity, either by study or by divine instruction, and Empiricism, which means that ethics and religious belief are human acquisitions that arise substantially from the predispositions in human nature. This forces us to think about where our ethics come from and what their values are, and how deeply they have affected our emotional lives.

It’s true that wars are best conducted by those who believe that they are guided by absolutes, especially divine absolutes. That view, however, when shared by two opposing armies, is the reason why we have been wading in blood for millennia. It would appear to me that humanity can move toward a humanistic ethic in which ethical beliefs and precepts are, if I may use the term, “sacralized” by a strong consensus, based on a modern informed study of the evolutionary process and its consequences. I think such an ethic can only arise from a more consilient view toward the humanities. If we can first sacralize our ethical precepts by general strong agreement and then valorize them with the symbols of communal unity and agreement, while keeping them subject to modification based on further study and discussion, we could build an ethical system that is just as strong as the ones validated by religion and one that is much more likely to be global, as opposed to the systems we have now which are mostly tribal.

Skeptic: Well, let’s get down to specifics. Can we come up with an evolutionarily-correct position or a consilience correct position on issues like abortion, animal rights, immigration, population and the environment, eugenics, genetic engineering, ethnic conflict and genocide? If you can’t give me specific answers, aren’t we just talking to each other?

Wilson: Well, that’s what people have been doing anyway, just talking to each other. Those who have the largest majority on their side and the greatest passion at the moment are the ones whose views prevail. I think it would be foolish to claim to have reached a powerful, enduring, and sacralized position on any of those issues based on what we know now. The prospect, however, is that with more knowledge and open discussion based on that knowledge, we could reach consensus. For example, on the issue of population and the environment, the facts about the risk of over-population and the accelerating destruction of the environment are so clear-cut now that if they were laid out before everyone, which we have not properly done up to the present time, the world would most likely move to a pretty solid consensus, even overriding the strong natalist views of some traditional religions. That’s one issue I’m pretty confident about.

Let me cite another one to show you that the empiricist view of the origin of ethical precepts is not just reckless relativism. The issue of incestuous sex, and even reproduction, has come up repeatedly. There have even been a small minority of thinkers who have suggested the incest taboo is just the last of the outdated sexual inhibitions. Now we know that is not the case. We have excellent evidence of the genetically dangerous effects of inbreeding. We know pretty precisely, in fact, what those increased risks are. We also know there is an epigenetic rule in mental development, the Westermarck effect, which, under most circumstances, causes people to become sexually desensitized to those with whom they are reared and to avoid having incest. Furthermore, we know that this is not only a trait of human cognitive development, but also of every one of the primate species that have been studied to date with this subject in mind. Incest avoidance is a very deep and ancient propensity of primate cognitive development. That evidence should effectively eliminate the last vestiges of the belief that incestuous sex and reproduction are permissible. That’s a fairly easy one, but nonetheless it illustrates the principle that empirically derived ethical precepts can gain consensus and become established.

Skeptic: Do you want to try any of the others, or are they still in the talking stage?

Wilson: The latter. These, of course, are the ones that have so many ambiguities and cross-cutting preferences and consequences that one can’t resolve them at the present time. Part of the problem is that the traditional religious positions, some of which have got to be wrong because many of them are in opposition to each other, have made any such discussion virtually taboo.

Skeptic: Let me take one that just comes to mind — a powerful, middle-aged male is alleged to have had a sexual involvement with a young female in a subordinate position. Is that something that we should look at based on human evolutionary history and say, “Hey, that’s just doin’ what comes natural.” Or should we regard it as an unallowable exploitation of an individual in a precarious position, which is precisely why we need laws to overcome our evolutionary predispositions, rather than to reinforce them?

Wilson: Both statements are correct. No one in their right mind would commit that form of the naturalistic fallacy, saying that anyone should feel free to do whatever they feel emotionally inclined to do. Human societies, like all primate and, in fact, all vertebrate societies, are based upon compromises and competitive conflicts. Therefore inequalities and even despotism are possible consequences. Since human morality is based on contract and consensus formation, these need validation as societies become more complex. We should be especially cautious in arriving at a moral consensus about the propensities evolution has fitted us, with, and the one you just cited is certainly an example.

Skeptic: We mentioned the naturalistic fallacy, which goes back to David Hume. When I asked Robin Fox about it, he said, “Hume was actually making a kind of anthropological observation. What Hume said is, ‘Isn’t it interesting, when you listen to people making moral arguments, how frequently and easily they jump from Is to Ought, without giving you the intervening reasons.’ Hume himself was quite willing to jump from Is to Ought” (Miele, 1996b, 84).

Wilson: I think you can go from Is to Ought, and we just reviewed an example of how.

Skeptic: Well, conservatives who are happy with gender-specific roles like to say either that they’re part of human nature or that God made us that way, except when it comes to sexual orientation. Then they say that homosexuality is unnatural. But a lot of liberal and left-wing individuals who wouldn’t touch human nature otherwise say that sexual orientation is inborn and can’t be changed. Doesn’t that show that there’s something inside us that resonates to the idea of natural law like the sympathetic vibration of a piano string? Does the fact that we make that transition so frequently and easily, as Hume originally noted, show that humans are predisposed to seek and accept “natural” explanations?

Wilson: I believe it shows that people tend to look after their own selfish interests if they can rationalize them. That’s primarily a primate trait. It’s also a rather lazy and ignorant way of thinking.

Skeptic: Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor mused that, “If there’s no God, anything goes.” Your whole point in arguing for consilience seems to be clearly opposed to an “anything goes” philosophy for the reasons you spelled out in the example of incest. So don’t we need concepts like God, a soul, and free will in order to practice morality and keep us from following our selfish interests?

Wilson: The Grand Inquisitor’s statement actually could be turned around to say, “If there is a God, anything goes,” because we’ve seen how in the evolution of human societies God has been invoked with great passion to justify every form of criminality, up to and including slavery and genocide. So much for the need for God in order to have morality.

Skeptic: How about free will?

Wilson: I spelled out how the free will issue can be handled in Chapter Six of Consilience: “The Mind.” To very briefly summarize, free will exists insofar as the ambit of ordinary human thought reaches. Perhaps a super-computer simulating the action of virtually every molecular system within every neuron of a person’s brain might be able to predict in advance how that person is going to act. But that is a theoretical construct so far beyond what is practical, that effective human action cannot be determined. If taken to that level, the issue of free will becomes a fruitless argument. At the common sense level of an individual being able to follow a wide range of intentions, however, free will certainly exists.

Skeptic: One of the pillars of sociobiology was explaining eusociality (true or higher social behavior in animal species) in terms of haplodiploid sex determination (i.e., where males derive from unfertilized [haploid] eggs; females from fertilized [diploid] eggs). That’s an example of reductionism at its best. But not all haplodiploid species are eusocial. Termites are not. And some eusocial species are not haplodiploid, the naked mole rat being an example. So if haplodiploidy is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for the evolution of eusociality, is the pillar of sociobiology starting to shake a little?

Wilson: Oh no. Sociobiology would do very well without kin selection. Kin selection is just one of many models derived from evolutionary biology that have been used to explain the origins of social behavior. I don’t want to sound glib about this. I put it that strongly to emphasize that what we’re referring to is not some kind of over-arching top-down system of explaining social behavior like those that have prevailed during most of the 19th and 20th centuries, including Freudianism and other classic grand theories. Sociobiology employs a natural science approach to explain the workings and origins of social behavior.

I happen to think that kin selection is a very powerful and well substantiated process, not only in social insects, but also in human beings. It doesn’t explain everything, but it’s very rare that a single factor like collateral selection (the selection among groups other than parent-offspring) is all-explanatory. A single factor can introduce a major biasing in evolution. The concept of collateral selection has held up very well. In the case of the social Hymenoptera (the order of insects that includes ants, wasps, and bees), there is plenty of evidence for other biasing factors besides haplodiploidy, which fits all of the eusocial insects, except for the termites. Species that tend to nest close to one another in the same place, such as solitary bees or wasps, are more likely to evolve into advanced social forms. So are species that take care of their young. I call these factors part of the Eusocial Complex. Multiple factor models are very common in evolutionary biology and they are testable.

Skeptic: Well, if the score in the game between sociobiology and its critics was 1-to-1 back in 1975, what is the score now?

Wilson: When you recognize that the term Evolutionary Psychology is the same thing as Human Sociobiology, I would say it’s now 10-1, in favor of Sociobiology.

Skeptic: Then why the need to change the name to Evolutionary Psychology? (For an introduction to the field see Miele, 1996a.)

Wilson: This is something of a puzzle. Evolutionary Psychology is the same subject as Human Sociobiology, but it’s been picked up because it contains the word “psychology.’’ Most of the investigators in that area obtain employment in departments of psychology or anthropology. It would be harder to obtain one of those job slots by identifying yourself as a biologist of any kind.

Skeptic: Why is that? Political correctness?

Wilson: No. I was going to come to that in a moment. The reason is the classic division of academic departments. The psychology department wants to cover all fields of psychology. So it’s a little easier to get a position in the psychology department if you bill yourself as some kind of psychologist, rather than some kind of biologist. However, since Evolutionary Psychology came along after the Sociobiology Wars of the 1970s, it’s a little bit more politically correct.

Skeptic: Let’s move on to even less politically correct topics. Suppose the comet Chicxulub failed to hit the earth, or that some of the great extinctions of the past had not taken place. Is there a consistent set of evolutionary pressures that would have led some species of dinosaur, or ant, or some other group, to develop a neurological complexity sufficient to support the cognitive complexity, behavioral complexity, even moral complexity of modern humans? If there’s life elsewhere in the universe, are there universal evolutionary pressures that would lead to neurological, behavioral, and even moral complexity over time? Or is that 19th-century progressivism?

Wilson: At the present time, that is an unanswerable, but very good question. We may have an answer when the natural sciences have become strong and consilient enough, because the answer requires our first reconstructing human cognitive evolution and the circumstances under which it arose, and then seeing how probable that same set of conditions would be in other large nonterrestrial biospheres. At the present time, it is virtually science fiction speculation. I did discuss the issue of human cognitive evolution in Promethean Fire, a book I wrote with Charles Lumsden (Lumsden and Wilson, 1983) where we developed the first theory of gene-culture coevolution. We reviewed the circumstances that might have contributed to this one species of Old World primate starting the runaway process of gene-culture coevolution.

Gene-culture coevolution was very likely a runaway process. Reaching the threshold to trigger that process must be very difficult because, obviously, out of hundreds of millions of species that have existed throughout geologic time, only one crossed it. There have been innumerable hypotheses about why that one species crossed the threshold — bipedalism, the challenge of a drying environment, and so on. Some day we may know why, but until then I think it’s useless to speculate about intelligent life on other planets.

Skeptic: What about the whole question of progress in evolution? Is there progress or are we just reading our own value system into the geological record?

Wilson: It’s very unfashionable, especially with the dull postmodernist cast that has seized some of our popular science writers, to speak of progress. The difficulty in the word is easily solved by simple semantic distinction. Everyone would agree that progress, in the sense of moving toward some predestined ultimate high point, does not exist in organic evolution. If, however, you mean the appearance of ever more cognitively complex and environmentally controlling species as a result of natural selection working over the course of evolutionary time, then progress does exist.

Skeptic: You spoke of gene-culture coevolution and you and Lumsden used the term culturgen. Richard Dawkins came up with the term meme and that one seems to have stuck, where culturgen did not. Why the need for two terms?

Wilson: Dawkins used meme in his best seller The Selfish Gene (1976) before Lumsden and I came up with the term culturgen. True to the consilient approach, Lumsden and I wanted to identify our term with a unit of cognition and so we used the node linkage nomenclature of cognitive scientists in the early 1980s. We suggested that if these nodes could be defined precisely, neurophysiologically as well as semantically, they would prove to be the ultimate elements of culture. So we called them culturgens. I’m very happy to call them memes and recognize that whatever that unit is, it still remains elusive.

Skeptic: But doesn’t your terminology emphasize that there’s an underlying genetic biological mechanism?

Wilson: Yes, and that’s why I would have preferred to have culturgen gain acceptance, but the world has taken to the word meme. I gladly accede to that and just hope that the word meme will eventually fit such a neurobiologically defined unit.

Skeptic: How far can we carry the concept of gene-culture coevolution? Let’s imagine two human societies, one that is communal and cooperative like the Quakers or the Amish, and the other similar to, say, Mafia families. Over the course of time, isn’t there going to be a biasing of both the culture and the genes in those two different groups for two different types of behavior?

Wilson: If they were totally reproductively closed, that is, breeding only among themselves, and this reproductive isolation was maintained by a great deal of selective pressure favoring certain predispositions as opposed to others, it could happen. But it would take quite a few generations. I’m not really sure that the behavioral predispositions of Mafia-type groups are that different from other groups. But let’s assume that some hypothetical group did stress a different morality or set of behavioral rules which were maintained for enough time for the genes predisposing one to that type of behavior to be favored, you could have a divergence between groups. Lumsden and I calculated that under certain conditions you could expect to see a substitution of one gene favoring a certain type of personality over another gene in something like 50 generations, the order of a millennium. The point is that societies with sufficiently different modes of conduct from other societies don’t hold together long enough to create that type of genetic diversity between groups.

Skeptic: But doesn’t any invention, or a new religion with different rules for marriage, or some new hygienic practice, immediately create some form of evolutionary pressure that affects the genetic composition of the next generation?

Wilson: It could. I’m not just being cautious in order to be politically correct. I’m being cautious because I could easily make a foolish misstep here. In theory what you say is correct. But in reality there are so many other restraining conditions as to make the likelihood of a single cultural change producing a corresponding genetic change problematic. From the viewpoint of bringing consilience to the natural and social sciences, the subject of the genetic underpinnings of human nature has been skirted around and avoided so long that our knowledge is in a primitive state at present. It’s risky, even apart from political correctness or incorrectness, for a scientist to speculate on the subject.

Skeptic: On page 53 of Consilience you write that the defining characteristics of science are: (1) repeatability, (2) economy (sometimes called parsimony or elegance), (3) mensuration (measurement), (4) heuristics (productivity, progress), and finally, (5) consilience. Clearly those are rules by which we can judge one scientific theory against another. But on what basis do we decide whether we want to play by that set of rules? Isn’t that an initial value choice, rather than a scientific question, as Jacques Monod argued in Chance and Necessity (1971)? Or does Darwinian selection provide a means by which to judge theories and metatheories by how well they work and survive?

Wilson: It’s the latter, of course. It’s what works. It’s not whether we have some innate preference or ideological derivative preference for one way of doing science over another. Consilience provides a natural history of what has proved to work in terms of providing logically and pragmatically interconnected theories that are capable of successfully explaining a wide range of phenomena, and often in a predictive way.

Skeptic: At Skeptic, we deal with science, but we also deal with a lot of pseudoscience, pseudohistory, and downright charlatanism. I want you to give me your reaction to the Frank Miele test as to whether something is science or pseudoscience, history or pseudohistory, or art or pseudoart (i.e., propaganda) — Does the scientist, the historian, or the artist already know the answers to all the questions they pretend to ask? In preparing interview questions or writing introductory articles for Skeptic (as opposed to technical writing jobs where I’m just describing the workings of an engineered product), I’m always amazed how I never really know where the article will lead me. It often takes me in terribly different directions than I had initially anticipated. Each answer ends up generating more questions, so that you never reach finality.

Wilson: If you have an open mind that’s true.

Skeptic: So, do you accept my distinction between the real and pseudo?

Wilson: I do indeed. The writer Eudora Welty once put it very well when she said, “How do I know what I think until I’ve written it?” A very good writer, like a very good scientist, sets out with some preconceptions and perhaps a creative urge to put something together, to tell a story, to describe an event or a phenomenon. In the case of a writer, from the depth of their own mind through introspection and reconstruction of narrative; for the scientist, perhaps much more by actual examination of phenomena, or running tests and the like. Although both are highly motivated to produce a coherent story or pattern at the end, they are creating it as they go along. That’s the mark of an open mind, the willingness to take in new information, even surprising and contradictory information, weaving it in and modifying the story as you go along. I like the Frank Miele test.

Skeptic: So what questions has Consilience raised in the mind of the man whom best-selling author Tom Wolfe (1996) has dubbed Darwin II, who has mapped the road to our understanding “the nature of our own precious inner selves?”

This interview appeared in Skeptic magazine 6.1 (1998)

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Wilson: You’re touching on what I think is one of the main virtues of the consilient approach. Mind you, what I’m doing is not expressing some original new idea of philosophy or science, but rather I’m trying to articulate what I consider to be the core, the spirit, and the most successful methods of the natural sciences, which are now in a position to influence the social sciences and humanities in a profound way. One of the great virtues of this approach is that it creates a map. It’s what I call gap analysis, borrowing a term from conservation biology where we analyze the distribution of organisms in parks and natural ecosystems to decide where reserves should best be placed. The consilient world view creates a map of what we know, what we don’t know, and what are the most accessible large areas awaiting exploration. This amounts to a replacement of the epistemological boundaries that have separated the natural sciences from the social sciences and humanities with the concept of a large and mostly unexplored borderland. That borderland is wide open to the disciplines of cognitive neuroscience, human behavioral genetics, evolutionary biology, including sociobiology, and environmental sciences. On the social science side, there are biological anthropology and cognitive psychology. By viewing the natural sciences, the social sciences, and the humanities in terms of consilience we can put to rest the idea that science has come to an end, another popular obsession making the rounds these days.

Skeptic: Thank you for a most enlightening and consilient interview. ![]()

References

- Boulding, K. 1984. “Toward an Evolutionary Theology” in Montagu, A. Science and Creationism. New York: Oxford.

- Caplan, A. (ed). 1978. The Sociobiology Debate: Readings on Ethical and Scientific Issues. New York: Harper.

- Dawkins, R. 1976. The Selfish Gene. NY: Oxford University Press.

- Gould, S. J.1996.“Nonoverlapping Magisteria.” Natural History. March:16–22, 60–62. Hollander, P. 1988. The Survival of the Adversary Culture. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

- Hölldobler, B. and E. O. Wilson. 1990. The Ants. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Holton, G., 1995. Einstein, History, and Other Passions, Woodbury, NY: American Institute of Physics Press.

- Limbaugh, R. 1993. “Commentary on E.O. Wilson’s ‘Is Humanity Suicidal?’”. Limbaugh Radio Broadcast of 31 May.

- Lumsden, C. and E. O. Wilson. 1981. Genes, Mind, and Culture: the Coevolutionary Process. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ___. 1983. Promethean Fire: Reflections on the Origin of Mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Miele, F. 1996a. “A Quick and Dirty Guide to Evolutionary Psychology and the Nature of Human Nature.” Skeptic. V. 4. No. 1:42–49.

- ___. 1996b. “The Imperial Animal Twenty-five Years Later.” Skeptic. V. 4. No. 1: 78–85.

- ___. 1997. “Living Without Limits: An Interview with Economist Julian Simon.” Skeptic. V. 5. No. 1: 54–59.

- Monod, J. 1971. Chance and Necessity: An Essay on the Natural Philosophy of Modern Biology. New York: Knopf.

- Needham, J. 1978. The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China. (C.A. Rowan, ed.) New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Popper, K. 1966 (1943). The Open Society and Its Enemies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Rorty, R. 1998. “Against Unity.” The Wilson Quarterly. Winter: 28–38.

- Ruse, M. 1996. From Monads to Man: The Concept of Progress in Evolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Sagan, C. 1996. Demon Haunted World. New York: Random House.

- Shermer, M. 1997. Why People Believe Weird Things. New York: W. H. Freeman

- Silverman, I. 1993. “Sociobiology and Sociopolitics.” Address to the European Sociobiological Society, August.

- ___. 1998. “Can Behavioral Science Change Society? Should We Want to Try?” Biopolitic (in press).

- Takacs, D. 1996. The Idea of Biodiversity: Philosophies of Paradise. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Williams, N. 1997. “Biologists Cut Reductionist Approach Down to Size.” Science Vol. 277, #5325, July 25: 476–477.

- Wilson, E.O. 1975. Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- ___. 1984. Biophilia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ___. 1993. “Is Humanity Suicidal?” New York Times. 30 May: 24–29.

- ___. 1994. Naturalist. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

- ___. 1998. Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. New York: Knopf.

- Wolfe, T. 1996. “Sorry, but Your Soul Just Died.” Forbes. 2 December: 211–223.

This article was published on December 27, 2021.