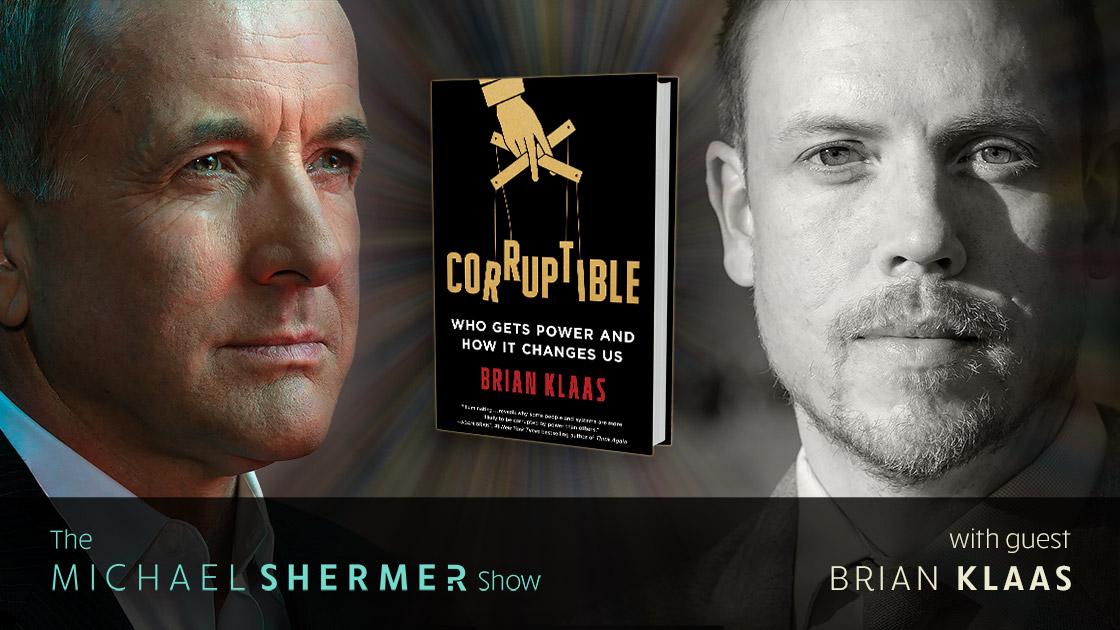

EPISODE # 238

Brian Klass on power and corruption, based on his book Corruptible: Who Gets Power and How it Changes Us

Does power corrupt, or are corrupt people drawn to power? Are entrepreneurs who embezzle and cops who kill the result of poorly designed systems or are they simply bad people? What sort of people aspire to power anyway? Are there individuals among us who should never be given the title of president, or CEO, or PTA leader lest they build their own dictatorship?

Michael Shermer speaks with Brian Klaas, a renowned political scientist, Washington Post columnist and creator of the award-winning Power Corrupts podcast, about his long sought answers to the above questions.

In his new book Klaas draws on over 500 interviews with some of the world’s top leaders — from the noblest to the most crooked — including presidents and philanthropists as well as rebels, cultists, and dictators, to get to the root of power and corruption. Klaas dives into how facial appearance determines who we pick as leaders, why narcissists make more money, why some people don’t want power at all and others are drawn to it out of a psychopathic impulse, and why being the “beta” (second in command) may be the optimal place for health and well-being.

If you enjoy the podcast, please show your support by making a $5 or $10 monthly donation.

In today’s eSkeptic we acknowledge the death of one of the giants of 20th and 21st century science, Edward O. Wilson, the entomologist, evolutionary theorist, and unifier of all knowledge. Many obits that include the details of his stellar career and engaging life have already been published in most media outlets, so here we reprint an extensive and intimate interview we published in Skeptic in 1998, Vol. 6, No. 1, conducted by our editor Frank Miele, upon the occasion at the time of the publication of Wilson’s game-changing book Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, which extended the Enlightenment belief that through science and reason humans can understand all aspects of the world — physical, biological, social, and even moral. The book inspired Skeptic Publisher Michael Shermer to write The Science of Good and Evil and The Moral Arc to see how far into the realm of morality and ethical theory science and reason can take us. Is this a realistic goal? Read Wilson’s thoughts on the matter in this illuminating conversation.

Above: Edward O. Wilson in 2003. Photo by Jim Harrison, CC BY 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

The Ionian Instauration

An Interview with E.O. Wilson on His Latest Controversial Book: Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge

Edward Osborne Wilson has had more impact on the borderland between the natural and the social sciences than anyone alive, possibly anyone since Charles Darwin. Perhaps that is why so astute an observer of the interrelationships between science and culture in contemporary America as Tom Wolfe, best-selling author of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Painted Word, The Right Stuff, and Bonfire of the Vanities, has dubbed Wilson “Darwin II,” the intellectual guide not to “the evolution of the species…but to the nature of our own precious inner selves” (Wolfe, 1996, 214). Pellegrino University Research Professor and Honorary Curator in Entomology of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University, Wilson is a member of the National Academy of Sciences, recipient of the Swedish Academy’s 1990 Crafoord Prize (the world’s most distinguished environmental biology award), the International Prize for Biology from Japan (1993), and the world’s leading expert on ants. He is also co-originator of the theory of island biogeography, a champion of preserving the rain forests and biodiversity (for which he has received the 1990 Gold Medal of the Worldwide Fund for Nature and the 1995 Audubon Medal of the National Audubon Society), and winner of two Pulitzer prizes in general non-fiction for On Human Nature (1978) and The Ants (1990), the latter along with co-author Bert Hölldobler.

Edward Osborne Wilson (1929–2021)

Wilson’s book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (1975) laid out the evidence for the evolutionary and genetic basis of social behavior across the animal kingdom. The fact that he dared to include a final chapter, “Man: From Sociobiology to Sociology,” set off the Sociobiology Wars of the late 1970s. That conflict was fought not only in academic journals and at conferences, but in campus protests and demonstrations. At a special symposium on sociobiology at the 1978 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), a member of the International Committee Against Racism (INCAR) dumped a pitcher of water on Wilson’s head as she and fellow demonstrators chanted, “Wilson, you’re all wet!” Skeptic Editorial Advisory Board member Stephen Jay Gould chastised the crowd by quoting Lenin on the inappropriateness of violence for mere radical posturing, as opposed to the attainment of worthy political goals, and referred to the incident, again in Lenin’s words, as “an infantile disorder of socialism.” Skeptic Editorial Advisory Board member Napoleon Chagnon tried to make his way to the podium to eject the protesters (Wilson, 1994, 348–350).

While his views on human nature have been anathema to many self-identified leftists, Wilson’s passionate pleas on behalf of preserving the rain forests and on the value of biodiversity have often been criticized by many on the political right. Julian Simon, the late pro-growth economist, praised Wilson as a “superb scientist,” but questioned the estimates of the increasing rates of animal extinctions that Wilson has cited in defense of environmental preservation (Miele, 1997). And in one of his zanier zingers, even for him, conservative radio talk show host Rush Limbaugh denounced Wilson’s article “Is Humanity Suicidal?” in the New York Times magazine (1993), as the ranting of a “radical liberal environmentalist who teaches at Harvard,” and who is “just the kind of guy the Clinton administration listens to and who is teaching our children” (Limbaugh, 1993). This must have come as news not only to Wilson and the Clinton administration, but all those left-wing demonstrators at Harvard.

The model of a kind and gentlemanly scholar, now nearing 70, Wilson has the ability both to ignite intellectual arguments that draw common fire from otherwise bitter enemies, and also to inspire affection and admiration from most of those who disagree vehemently with him, and all of those who know him personally. His latest book, Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (Knopf, 1998), has set off yet another conflagration in the intellectual and academic journals and conferences and their associated e-mail networks.

In Consilience, Wilson argues that the natural sciences, based as they are on extensions of Darwin’s seminal vision, have now reached a state of sufficient maturity that they can light the way through the borderlands connecting those disciplines with not only the social sciences, but also religion, ethics, politics, and the arts and humanities. The idea of basing anything on evolution is anathema to some, and the biologizing of social science sets off an immediate protest by others. Not only religious and political zealots, but contemporary philosophers like Richard Rorty and Skeptic icons like Stephen Jay Gould, the late Carl Sagan, and Michael Shermer, question not only our ability, but the desirability of trying to unite such traditionally discrete domains as science and religion. To Wilson, eschewing consilience in favor of maintaining epistemological boundaries between the disciplines has produced a result analogous to fragmentation in a computer system, in which the scattering of files over non-contiguous areas of memory increasingly degrades performance until it eventually brings the system to its knees. In its place Wilson calls for an instauration, a term coined by Sir Francis Bacon (one of the heroes of Consilience), meaning “a new beginning” (1998, p. 27), of the dream of the pre-Socratic Greek philosophers, who walked the Ionian shores and searched for unity in the nature of all things. Consilience may well be the most influential book in setting an overall direction for contemporary intellectual thought since Karl Popper’s 1943 The Open Society and Its Enemies. Here is E. O. Wilson on Consilience and its Discontents.