Hurricane Ophelia on September 10, 2005, captured by the Expedition 11 crew aboard the International Space Station. Courtesy of NASA

Enviro-Buzz

This week, we link to two articles by Chris Mooney, one of our speakers at the Environmental Wars conference this year, who writes on issues at the intersection of science and politics. Mooney is the Washington correspondent for Seed magazine — an emerging science media company whose mission is “to help nurture a science-savvy global citizenry by increasing public interest in science and public understanding of science.”

In Heeding Cassandra, Mooney reports on the ignored warnings of scientists and engineers prior to Hurricane Katrina. READ the article >

In Skipping Ahead, Mooney reviews Andrew Revkin’s book The North Pole Was Here: Puzzles and Perils at the Top of the World — a book written to explain global warming to everyone aged 10 and up! READ the article >

Join us on the weekend of June 2–4 as we continue to disentangle politics and opinion from the science about our planet’s health. Please note that Sunday’s optional geology tour is now sold out! Register soon, and participate in the dialogue:

CANCELED: Genes in Conflict lecture

(instead we present Decoding the Da Vinci Code)

Dr. Robert Trivers lecture, Genes in Conflict, scheduled for May 7th, 2006 at Caltech, has been canceled. In it’s place, we have scheduled a lecture you won’t want to miss…

The Da Vinci Code, close-up of book cover

Decoding the Da Vinci Code

with Tim Callahan

Sunday, May 7th, 2 pm

Baxter Lecture Hall, Caltech

On May 19th, the film version of the wildly popular book by Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code (over 40 million copies in 25 languages sold), will be released to considerable fanfare and media hype. Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, head of doctrinal orthodoxy for the Vatican, issued an official statement on behalf of the Catholic Church, calling the novel “a sack full of lies” and urging Christians not to read the book or see the movie. Even though the book is a novel, Brown claims that it is based on historical facts that, if true (and many people believe that they are true), would revolutionize not only all of the Christian religion, but much of history as well. The central claims is that Jesus and Mary Magdalene were married and sired a royal bloodline that continues to this day, and that a secret society of some of history’s most famous scientists and artists has been dedicated to preserving these ancient secrets for almost a thousand years. If ever there were an extraordinary historical claim that requires extraordinary historical evidence, this is it. How good is the evidence?

Tim Callahan, Skeptic magazine religion editor and author of the books Bible Prophecy and The Secret Origins of the Bible, will explore these and other biblical mysteries recently in the news, such as the “Gospel of Judas” (in which Jesus’ disciple is not a traitor) and other extra-biblical gospels that portray Jesus in a different light. Callahan will review biblical scholarship and show how we know who wrote the Bible and why they wrote it.

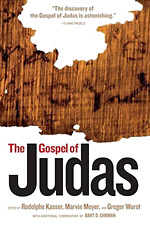

In this eSkeptic leading up to his talk, we present Tim Callahan’s review of The Gospel of Judas, National Geographic Channel, Sunday, April 9, 2006; and The Gospel of Judas (National Geographic, 2006, ISBN 1426200420), by Bart Ehrman (Commentary), and Rodolphe Kasser, Marvin Meyer, and Gregor Wurst (Eds).

“One of You Will Betray Me”

by Tim Callahan

Was Judas the vilest of villains, as portrayed in the four canonical gospels, or was he a saint, acting out the role of betrayer to aid Jesus in fulfilling his role as the one who would rise from the dead? My answer, in short, is that Judas was the guy who drew the short straw; but more on that later.

The Gospel of Judas, which aired on the National Geographic Channel on Sunday, April 9, 2006 (see the book of the same title upon which the show was based, published by National Geographic), deals with a Gnostic Christian text in which Judas is presented as the foremost disciple, who is taken aside by Jesus and given a special teaching. This is not unusual for Gnostic gospels. The Gospel of Mary Magdalene, written in Coptic (like the Gospel of Judas), the language spoken in Egypt in Roman times, also claimed a special revelation — a special teaching — imparted to Mary, and her alone, by the risen Jesus. This in itself is a bit shocking in such a male dominated society; but the common view of Judas as the arch-betrayer is so entrenched in our culture that the reversal of his character portrayed in the Gospel of Judas can be jarring even to secular readers.

The National Geographic program dealt not only with this startling view of Judas, but with the rather harrowing history of the discovery of the ancient text and its historical validity. The crumbling papyri that comprised the original codex were discovered in Egypt in 1980, but were stolen, recovered, and subsequently hidden in a safe deposit box, not coming to light until 2002. Since the papyrus pages had not been properly cared for, they were in terrible condition when they were finally examined by experts, and their fragmented pieces had to be painstakingly fitted together before a decent translation could be made.

Radiocarbon dating places these papyri at CE 280 ± 50 years, making the text a third or fourth century copy. We know that the Gospel of Judas was in existence earlier, however, because Irenaeus, then Bishop of Lyons, railed against it in his Against the Heresies (Chapter 31, pp. 102, 103), along with other Gnostic texts, ca. CE 180:

Also Judas, the Traitor, they say, had exact knowledge of these things, and since he alone knew the truth better than the other apostles, he accomplished the mystery of the betrayal. Through him all things in heaven and earth were destroyed. This fiction the adduce and call it the Gospel of Judas.

So, the Gospel of Judas and its doctrines were established as far west as Gaul by the later part of the second century. However, whether or not this gospel is as old as the gospels that made it into the Bible is difficult to say. Broadly speaking, the canonical gospels can be dated by two methods. First, they can be dated in relation to each other. Both Matthew and Luke copy the text of Mark almost verbatim, adding their own material on the Nativity, which is not mentioned in Mark, as well as their own resurrection stories. They also include sayings of Jesus, possibly from a hypothetical lost source called “Q.” Some of these sayings also appear in the Gnostic Gospel of Thomas. These three gospels, Mark, Matthew and Luke, are referred to as the Synoptic Gospels, a term invented by Johan Griesbach in 1744, meaning “seen together.” These gospels are “seen together” because of the similarities resulting from Matthew and Luke copying Mark. The order of events in all three is the same, as are the miracles. The Gospel of John, on the other hand, inserts different miracles. Both the raising of Lazarus and turning water into wine at the wedding feast at Cana are found only in John. Jesus scourging the money-changers from the Temple, seemingly the proximate cause of his arrest by the Temple authorities in the Synoptic Gospels, is placed right after the wedding feast in Cana, near the beginning of Jesus’ ministry, in John. These facts, along with the more sophisticated theology of John, as witnessed by the beautiful poem that opens that gospel, lead most experts to conclude that John was written after the Synoptic Gospels. So, the relationship of the gospels in time is that Mark was written first, then Matthew and Luke, then John.

Thus, if we can date Mark, we can date the others in relation to it. In the “little apocalypse,” also called the Olivet Discourse, in which Jesus and his disciples are sitting on the Mount of Olives opposite the Temple, Jesus predicts the destruction of the Temple (Mark 13:2). This happened in CE 70, when the Romans crushed the Jewish revolt and utterly destroyed Jerusalem. This is either divinely inspired prophecy, written before the fact, or history, written after the fact. In Mark 8:38–9:1 (parallel verses in Mt. 16:27, 28 and Lk. 9:26, 27) Jesus predicts the end of the world and the second coming within his own generation. Since this did not happen, we can safely dismiss divine inspiration and assume that Mark was written after the Roman sack of Jerusalem in CE 70. In fact, Mark is generally dated as having been written ca. CE 70, while Matthew and Luke are thought to have been written ca. CE 80 and John ca. CE 90. This squares rather nicely with the Rylands Fragment, a scrap of papyrus from the Gospel of John, dated at ca. CE 125. Since Irenaeus found the Gospel of Judas already being expounded among an entrenched community of Gnostic Christians in the western half of the Roman Empire in CE 180 in what is now France, we must assume it was in existence earlier, possibly as early as the canonical gospels.

One criticism of the Gnostic gospels, leveled by orthodox Christians, is that their doctrine was elitist and exclusionary, claiming secret wisdom for the few and excluding the many, in direct conflict to the message of those gospels found in the canon. However, this claim of inclusiveness is not entirely true. In Mark 4:11,12 Jesus tells his twelve disciples: “To you has been given the secret of the kingdom of God, but for those outside everything is in parables, so that they may indeed see but not perceive, and may indeed hear, but not understand; lest they turn again, and be forgiven.” The word translated as “lest” is mepote in the original Greek, meaning literally “not ever.” Inserting this in place of “lest” in Mark 4:12, we get: “so that they may indeed see but not perceive, and may indeed hear, but not understand; [that] not ever they turn again, and be forgiven.”

Here, then, Jesus is saying, quite harshly, that salvation is only for the select few, a message that the parallel verses in Matthew and Luke only soften slightly. Thus, the Gnostic claim of special revelation for the select few may not be that far from the original message of Jesus. Giving a select role to Judas, rather than making him a traitor, may, however seem too great a departure from the orthodox Christian message.

Yet, Jesus early on tells his disciples that he must go to Jerusalem and there be put to death that he might rise again after three days (Mark 8:31–33):

And he began to teach them that the Son of man must suffer many things, and be rejected by the elders and the chief priests and the scribes, and be killed, and after three days rise again. And he said this plainly. And Peter took him, and began to rebuke him. But turning and seeing the disciples, he rebuked Peter and said, “Get thee behind me, Satan! For you are not on the side of God, but of men.”

Since the Passion was foreordained, perhaps Jesus had complicity in his own arrest and execution, first by provoking the Temple authorities with the incident of interfering with the money changers, then by setting up his nighttime arrest, then finally by refusing to defend himself and even uttering what the high priest would have to see as blasphemy. Judas’ part in this would have been to lead the Temple troops to the garden to arrest Jesus, and this would have been under the direction of Jesus. If this is the case, then my theory that Judas was the one who drew the short straw — which I merely offer as one alternative without apology or defense — would apply. Perhaps, in the original incident, Jesus did not say, “One of you will betray me,” as a prediction, but rather, as a command; and Judas, as the one who happened to be dipping into the bowl at the same time as Jesus, was summarily given the onerous job.

An examination of the original Greek of the gospels may help here. The word translated as “will betray” is paradosei, a form of the verb pardidomi. This word means roughly “deliver over” and, depending on the context in which it is used, can mean anything from arrest or betray to simply making a delivery or giving a present. So Jesus may have said, “One of you is to hand me over.” The reaction of the disciples to this is somewhat curious, at least in the English translation (Mark 14:17–20):

And when it was evening he came with the twelve. And as they were at the table eating, Jesus said, “Truly, I say to you, one of you will betray me, one who is eating with me.” They began to be sorrowful, and to say to him and to one another, “Is it I?” He said to them, “It is one of the twelve, one who is dipping bread in the same dish with me.”

It seems odd that the disciples would ask, “Is it I?” if betrayal is involved. On the other hand, their question makes perfect sense if Jesus was originally commanding that one of them betray him. However, the English translation is a bit faulty. In the original Greek, the question is: “Meti ego?” This translates more precisely as, “Not I?” Perhaps the best translation would be a horrified, “Surely it is not I?”

Of course, the idea of referring back to “the original Greek” exposes yet another problem. Assuming what is narrated in Mark was an actual historical incident, Jesus and his disciples would have been speaking Aramaic, a Semitic language, rather than Greek, an Indo-European language. Thus, all the fine shadings of meaning in the Greek words chosen by the author of Mark, while useful in determining the gist of what the author was writing and the state of mind of the early believers in the Christian church, would be irrelevant in pinpointing what Jesus actually said.

In fact, whether we consider Judas to be the ultimate traitor, a saint helping Jesus attain the resurrection, or the guy who got the short straw may well be historically irrelevant, since the betrayal, like the whole Passion narrative, is more likely grand storytelling rather than history. Consider the entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, with the Jews hailing Jesus as a king and shouting, “Hosannah!” i.e., “Free us!” This is not something the Romans would have historically ignored. In CE 45 a would-be Messiah named Theudas gathered his disciples on the east bank of the Jordan river. He believed the river would dry up at the point of his crossing, as it did for Joshua, and he would cross, dry shod, to begin the liberation of Israel. All the Romans really had to do was to wait for Theudas to get his feet wet and be thoroughly discredited. Instead, the Roman procurator, Cuspius Fadus, sent out a detachment of cavalry that attacked and killed or dispersed Theudas’ followers. Theudas was taken into custody and beheaded (Josephus Antiquities Book 20, Chapter 5). Thus, the Roman response to gestures of Jewish independence was gratuitously violent. Yet, if the gospel accounts are to be believed, the Romans stood by and did nothing on Palm Sunday.

Like the Palm Sunday pageantry, the betrayal at night, with Judas having to demonstrate who Jesus was by his famous kiss, does not ring true. If Jesus were actually a pubic figure considered dangerous enough to arrest in the first place, then why would Judas have to finger him for the arresting party? Jesus even tells those arresting him as much. Nor is there any indication that, after the incident with the moneychangers, Jesus has gone into hiding. In fact, the betrayal itself is pointless and without motivation. The Temple authorities did not need a betrayer, and there is no compelling reason given for Judas to suddenly turn on Jesus. The unreality of the incident continues when one of the disciples takes a sword and cuts off the ear of the high priest’s servant. Yet those arresting Jesus make no reprisals. Was Jesus even arrested by the temple authorities, then turned over by them to the Romans; or did the Romans simply arrest Jesus themselves? While the supposed actions on the part of the Sadducees would be reasonable — arresting a trouble-maker and turning him over to their Roman masters as a demonstration of loyalty — the Romans themselves would have had ample reason to arrest and execute anyone showing up in Jerusalem claiming to be the Messiah.

If the portrayal of Judas in the Gnostic Gospel of Judas is closer to the truth than that of the base traitor — again assuming that Judas and the betrayal are at all historical — we would expect his fate to be different from that of exclusion and ignominious death as implied by Mark and made explicit in Matthew and Luke. In Matthew, Judas hangs himself in remorse for his evil deed. However, as betrayer of his rightful master, he was only replaying an Old Testament story. In 2 Samuel 17:23, when Ahithophel, who has been supporting Absolom’s revolt against his father David, sees that the revolt is going to fail, he goes home and hangs himself. In the entire Bible the only two people to hang themselves are Ahithophel, who betrayed his king, David, and Judas (in the Matthean account), who betrayed his Messiah. Luke has Judas buy a plot of land with his blood money, then has his guts mysteriously burst asunder as he is looking down at his field (Acts 1:18).

Yet, in Paul’s summary of the post-resurrection appearances of Christ we are told (1 Corinthians 15:4–7): “that [Jesus] was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. Then he appeared to more than five hundred brethren at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles.”

Since, after first appearing to Peter (Cephas), he then appeared to the twelve, Paul, writing prior to CE 60, seems to be including Judas among those whom Jesus honored with a post-ressurection meeting. This would appear to validate either the idea of Judas as orchestrating the Crucifixion at the behest of Jesus, or even the idea that there was no betrayal, staged or otherwise.

However, there is a problem with this account: These may not actually be the words of Paul. In his recent book Misquoting Jesus, Bart Ehrman points out that, though Luke was familiar with Paul, he does not seem to have remembered the detail of the more than 500 people to whom Jesus appeared at one time. Certainly, if Luke were aware of this event, he would have used it in his own resurrection account. This would be a stunning proof of the resurrection and the divinity of Christ. Yet Luke, seemingly aware of the details of Paul’s life, does not know of the 500, indicating that Paul did not know either, and that this stunning detail was added by a later scribe. There is a curiously fractured quality to the above quote that shows a clumsy insertion. First, Jesus appears to Peter, then the twelve, then the 500, a widening circle of people. Then, and only then, does he appear to his brother James, who was the head of the church in Jerusalem, then to all the apostles. So the question arises: Are the 500 the only later addition, or has the whole text of 1 Cor. 15: 4–7 been hopelessly corrupted?

In the trailers advertising the National Geographic program, the Gospel of Judas was portrayed as potentially rocking Christendom to its foundations with its portrayal of Judas as closer to Jesus than the other disciples. Of course, it will do no such thing. Even if it were acknowledged to be the true story of the events of the Passion, it does not change the message of salvation through the Crucifixion and Resurrection. It only alters the position of Judas. That the Gospel of Judas can only be dated with any certainty to the latter part of the second century is reason enough for most orthodox believers to summarily dismiss this jarring narrative. The only way any Gnostic gospel will make any headway against believers who might be upset by its content would be for a papyrus codex to be solidly dated to at least the end of the first century, something that is unlikely to happen.

There are other reasons the Gnostic gospels are unlikely to shake the Christian world. First, their theology only plays well to a small elite because they believed that Yahweh, the God of Israel and the Old Testament, was actually a deceiver, the demiurge who created a material world of deception, and that matter is evil and that Yahweh is humanity’s antagonist who killed Christ, the true God, only to be foiled by the Resurrection. Not only is this offensive to orthodox Christians, it is as well offensive to those of us unbelievers who might enjoy such material pleasures as sexual love and good food. Second — Mark 4:12 notwithstanding — orthodox Christianity’s triumph over its more esoteric rivals does to some degree involve a message that is more accepting of the common person. Finally, the Gnostic gospels do not stand up well against the canonical gospels in substance. Most of them are brief collections of somewhat obscure aphorisms, i.e. they are “sayings gospels.” None of them match the drama of, for example, the Passion narrative. In the end, the gospels of Mark, Matthew Luke and John, while largely unhistorical, tell a better story.

References

- Ehrman, Bart D. Misquoting Jesus San Francisco: Harpers San Francisco, 2005.

- Flavius Josephus (translated by William Whiston) ca. CE 90 (1987). The Antiquities of the Jews (in The Works of Josephus) Hendrickson Publishers.

- Irenaeus (translated and annotated by Dominic J. Unger, with further revisions by John Dillon) ca. CE 180 (1981). Against the Heresies Book 1; Ancient Christian Writers vol. 55. New York: Paulist Press.