It started with a phone call. “Is this Stephen Bloom?” an emphatic voice asked out of the blue one spring morning seventeen years ago. Without waiting for a response, the caller sprinted ahead. “Well, this is Jane Elliott and I want to talk to you!” I had never spoken with or met Elliott before and I had no idea why she’d be calling me. She seemed insistent and determined. The only thing I knew about Elliott was a provocative classroom experiment credited to her.

For a decade, Elliott, a teacher in a small, rural Iowa town, had separated her third-grade students, for two days, into two groups—those with blue eyes and those with brown eyes. On the first day, she told the blue-eyed children that they were genetically inferior to the brown-eyed children. She instructed the blue-eyed kids that they wouldn’t be permitted to play on the jungle gym or swings. They’d have to use paper cups if they wanted to drink from the water fountain. They wouldn’t be allowed second lunch helpings. The next day, Elliott switched the students’ roles. The brown-eyed kids would now be considered inferior. The experiment was Elliott’s way of showing eight- and nine-year-old White children what it was like to be Black in America. Starting in the mid-1980s and for the next thirty-five years, Elliott would increase the experiment’s voltage by trying it out on adults in thousands of workshops worldwide.

I asked Elliott why she had called me, and without hesitation, she responded, “Because I want you to write a book about me.” Elliott’s moxie piqued my curiosity, and as soon as I got off the phone, I set out to learn more.

Years before the Black Lives Matter movement or the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer in the summer of 2020, Elliott, a White woman from out-of-the-way Iowa, had transformed herself into an international authority on all issues of racism and bias. An award-winning network TV documentary had aired about her, followed by a starring role at a headline- sparking White House conference on education. By 1984, Elliott had left her public school teacher’s job in Riceville, Iowa (population: 806), sixteen miles from the Wisconsin state line, and had taken the blue-eyes, brown-eyes experiment on the road. She tried it on tens of thousands of adults, in the United States, Canada, Europe, the Middle East, and Australia. She traveled to conferences and corporate workshops.

She took the experiment to prisons, schools, and military bases. She appeared on Oprah five times. Elliott became a standing-room-only speaker at hundreds of colleges and universities. In the process, she had turned herself into America’s mother of diversity training.

Elliott was so successful at what she did that she was granted membership in the historic pantheon of the West’s most revered educators: Plato, Aristotle, Horace Mann, Booker T. Washington, John Dewey, Maria Montessori, Jean Piaget, and Paulo Freire. In 2004, the American publishing giant, McGraw Hill, created a multipanel poster suitable for classroom display that included Elliott along with the other venerated thinkers and teachers. To me, Elliott’s separation of students based on their eye color seemed like a risky experiment that raised all kinds of ethical issues. In fact, as I was to learn, the experiment had been inspired by Nazis, as Elliott would be the first to admit. She had lied to impressionable children who trusted her. She had told them that half of the class was less intelligent because of their eye color, because of their genetics.

The experiment became so real that fistfights erupted on the Riceville Elementary School playground. That seemed bad enough. But Elliott did nothing to stop the fights. She encouraged them, based on the children’s newly granted superiority or inferiority. That was part of duping the children into thinking that the experiment was real.

Elliott had constructed a gut-wrenching, true-life nightmare in order to make an indelible point that would stay with her students for the rest of their lives. In essence, she tried to induce a dose of racism into the minds of the third graders.

* * *

It all began the day after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968, when Jane Elliott asked her all-White third-grade students “How do you think it would feel to be a Negro boy or girl? It would be hard to know, wouldn’t it, unless we actually experienced discrimination ourselves. Would you like to find out?”

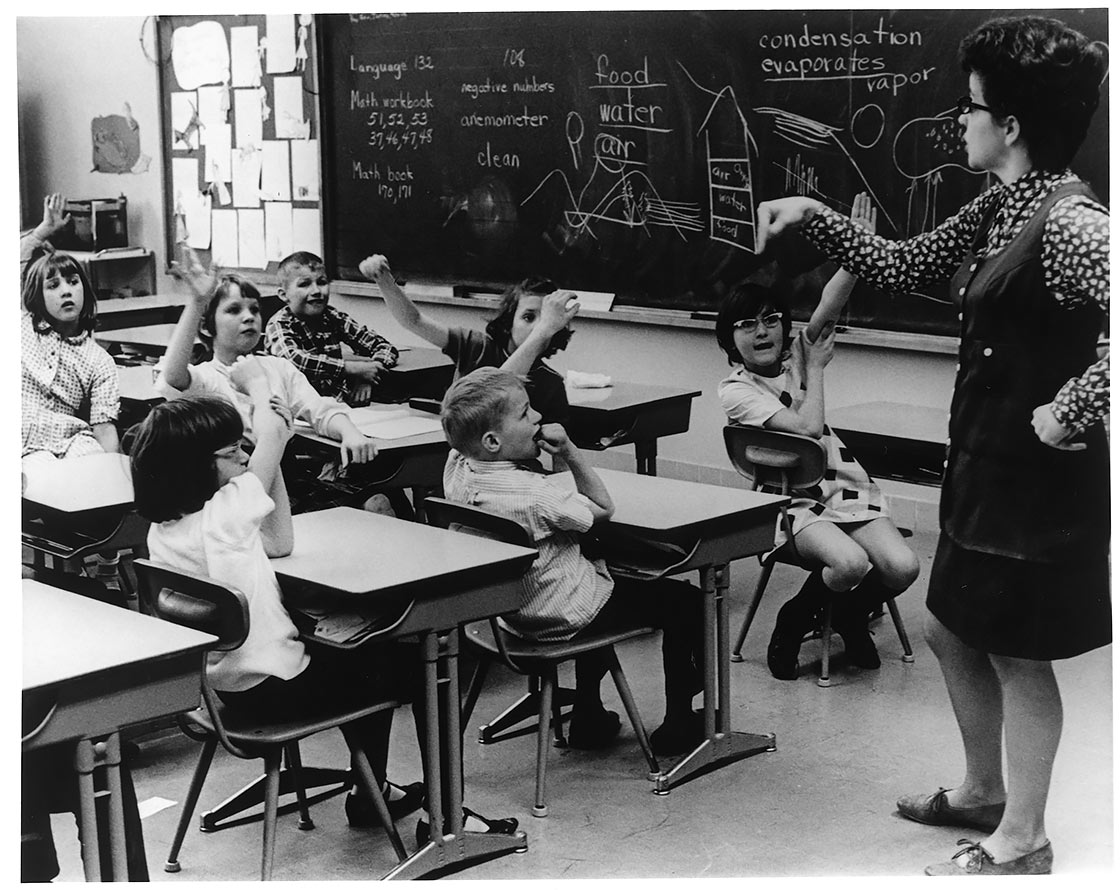

A spontaneous cheer arose from the children. YAAAAAAAAY! And so began one of the most astonishing exercises ever conducted in an American classroom. That spring morning 50 years ago, the blue-eyed children were set apart from the children with brown or green eyes. “It might be interesting to judge people by the color of their eyes,” Elliott teased. “Would you like to try?” Elliott then pulled out green construction paper armbands and asked each of the blue-eyed kids to wear one. “The browneyed people are the better people in this room,” Elliott began. “They are cleaner and they are smarter.”

“They are not,” one blue-eyed boy said under his breath from the group in the back. “Oh, yes, they are!” Elliott said, her eyes open wide. She wagged her index finger at the blue-eyed boy with the audacity to question her. “Brown-eyed people are more intelligent than blue-eyed people. It’s about time you knew the truth. You’re old enough to know this.”

Elliott issued more directives. “All you brown-eyed children, push your desks to the front of the room.” The children looked puzzled. “You heard me. Push them to the front. You’re the smarter kids. That’s where you belong!” The comment didn’t seem to register with the children, so Elliott repeated it. “Go ahead,” she told the brown-eyed group. “You ought to be sitting up front. Blue-eyed children, push your desks to the back. As far away as you can!”

She knew that the children weren’t going to buy her pitch unless she came up with a reason, and the more scientific to these Space Age children of the 1960s, the better. “Eye color, hair color and skin color are caused by a chemical,” Elliott went on, writing MELANIN on the blackboard. Melanin, she said, is what causes intelligence. The more melanin, the darker the person’s eyes—and the smarter the person. “Brown-eyed people have more of that chemical in their eyes, so brown-eyed people are better than those with blue eyes,” Elliott said. “Blue-eyed people sit around and do nothing. You give them something nice and they just wreck it.” She could feel a chasm forming between the two groups of students.

“Do blue-eyed people remember what they’ve been taught?” Elliott asked. “No!” the brown-eyed kids said. Elliott rattled off the rules for the day, saying blue-eyed kids had to use paper cups if they drank from the water fountain. “Why?” one girl asked. “Because we might catch something,” a brown-eyed boy said. Everyone looked at Mrs. Elliott. She nodded. As the morning wore on, brown-eyed kids berated their blue-eyed classmates. “Well, what do you expect from him, Mrs. Elliott,” a brown-eyed student said as a blue-eyed student got an arithmetic problem wrong. “He’s a bluey!”

Then, the inevitable: “Hey, Mrs. Elliott, how come you’re the teacher if you’ve got blue eyes?” a browneyed boy asked. Just before Elliott could answer, brown-eyed Steven Knode jumped in. “If she didn’t have ’em blue eyes, she’d be the principal!” Elliott couldn’t help but grin, at least to herself, not just for Steven’s insight, but because Mr. Brandmill, the principal, did, in fact, have brown eyes.

Next, she informed the children that no one from the blue-eyed group would be allowed on the playground equipment, because, she said, “They’re careless. Everyone knows that. They might break something.” Elliott went further, instructing the brown-eyed children not to allow any of the blue-eyed kids to play with them—even if they were friends. “Brown-eyed children need to play only with brown-eyed children. Blue-eyed children, you play among yourselves. There will be no exceptions. Does everyone understand?” “Yes, Mrs. Elliott.” Elliott issued more rules. The blue-eyed children would have to wait for the brown-eyed students to finish before being allowed to eat lunch. For recess, the brown-eyed children would get five more minutes. “Do you understand, children? Have I made myself clear?” Yes, Mrs. Elliott!

For the rest of the morning, Elliott was unrelenting. While on the playground, brown-eyed Bruce Fox would later recall, “Mrs. Elliott told a boy who was getting bullied that the next time that happens, ‘You smack ’em in the nose.’ She put her fingers together in a fist to show how it ought to be done.” If blueeyed students were playing jump rope or kickball, Fox remembered, Elliott urged the brown-eyed kids, “You take it away from them! That’s your right! Do it!” A brown-eyed student, Debra Anderson, recalled, “One of my friends had blue eyes, and I couldn’t play with her. I kinda hung out by myself and played on the swings and the monkey bars. I felt sick.”

* * *

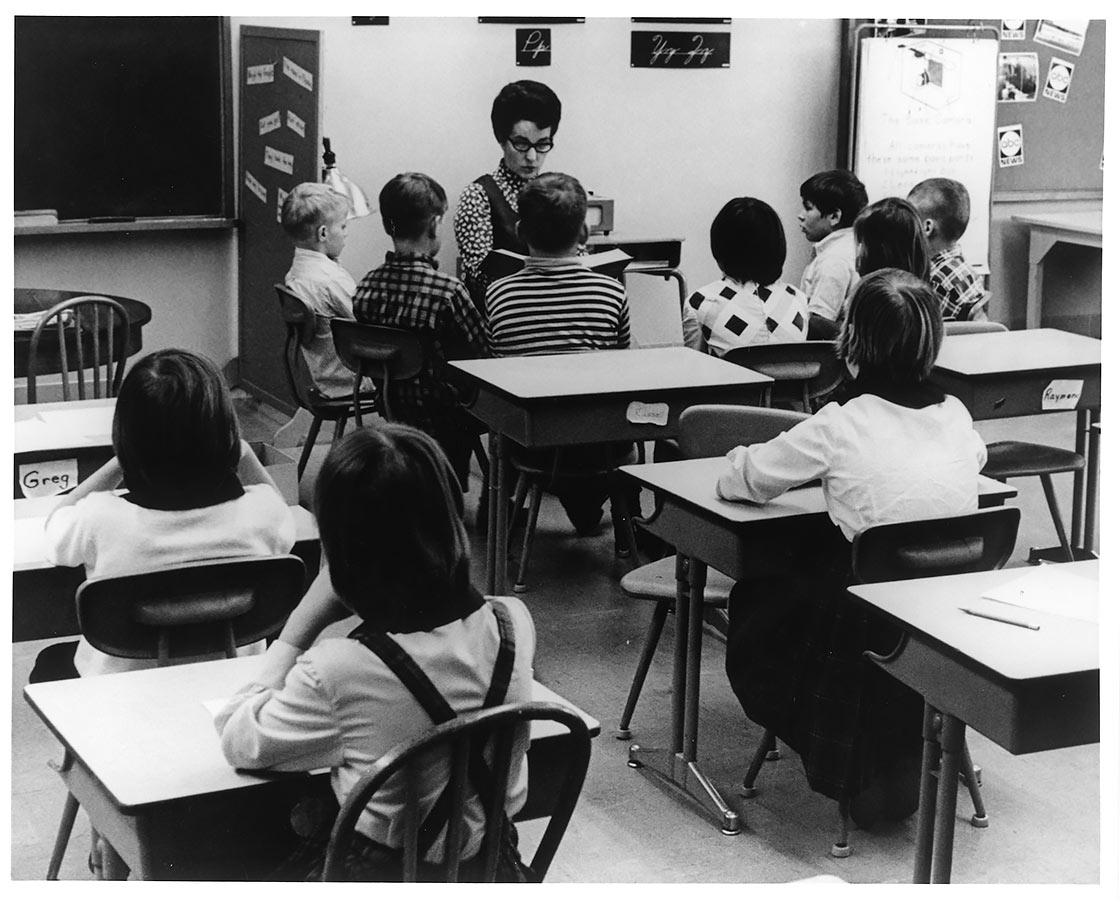

At lunchtime, Elliott hurried to the teachers’ lounge. She described to her colleagues what she’d done, remarking how several of her slower kids with brown eyes had transformed themselves into confident leaders of the class. Withdrawn browneyed kids were suddenly outgoing, some beaming with the widest smiles she had ever seen on them. She asked the other teachers what they were doing to bring news of the King assassination into their classrooms. The answer, in a word, was nothing.

Back in the classroom, a smart, tall, blue-eyed girl by the name of Carol Anderson, who never had problems with arithmetic, started making all kinds of mistakes when Elliott called on her. When Carol walked across the room, her shoulders slumped and she dragged her feet. Carol had always had a ramrod-straight posture, but since the morning, she had turned into a different person. Anyone could see that all the confidence that had once defined her had disappeared. During recess in the schoolyard, Carol, flushed and red in the face, came running to Elliott, sobbing. Three brown-eyed girls had ganged up on her, and one of them had hit her, warning, “You better apologize to us for getting in our way because we’re better than you are! Mrs. Elliott said so!”

On Monday, Elliott reversed the exercise, and the brown-eyed kids were told how shifty, dumb and lazy they were. Later, it would occur to Elliott that the blue-eyed kids were much less nasty than the browneyed kids had been, perhaps because the blue-eyed kids had felt the sting of being ostracized and didn’t want to inflict it on their former tormentors.

When the exercise ended, some of the kids hugged, some cried. Elliott reminded them that the reason for the lesson was the King assassination, and she asked them to write down what they had learned. Typical of their responses was that of Debbie Hughes, who reported that “the people in Mrs. Elliott’s room who had brown eyes got to discriminate against the people who had blue eyes. I have brown eyes. I felt like hitting them if I wanted to. I got to have five minutes extra of recess.” The next day when the tables were turned, “I felt like quitting school…. I felt mad. That’s what it feels like when you’re discriminated against.”

Elliott shared the essays with her mother, who showed them to the editor of the weekly Riceville Recorder. He printed them under the headline “How Discrimination Feels.” The Associated Press followed up, quoting Elliott as saying she was “dumbfounded” by the exercise’s effectiveness. “I think these children walked in a colored child’s moccasins for a day,” she was quoted as saying. That might have been the end of it, but a month later, Elliott says, Johnny Carson called her. Not an assistant, a producer, or a long-distance operator. It was Carson himself. Before Elliott could catch her breath, Carson announced, “We’d like you to come on the show and talk about the experiment you did on the kids in your class, the one separating the blue-eyed kids from the brown-eyed kids.”

Carson’s invitation to Elliott to appear on the show had been an experiment itself. A year earlier, Carson had told author Alex Haley for a Playboy interview that he sympathized with Black protesters. In a restrained, allholds- barred interview, he allowed, “It all comes down to just one basic word: justice—the same justice for everyone— in housing, in education, in employment and, most difficult of all—in human relations. And we’re not going to accomplish that until all of us, Black and White, begin to temper our passion with compassion.”

Elliott flew to the NBC studio in New York City. On the Tonight Show Carson broke the ice by spoofing Elliott’s rural roots. “I understand this is the first time you’ve flown?” Carson asked, grinning. “On an airplane, it is,” Elliott said to appreciative laughter from the studio audience. She chatted about the experiment, and before she knew it was whisked off the stage.

Elliott’s message on Tonight Show No. 1442 came across blunt and unfiltered. Blacks in America were treated as second-class citizens and Whites didn’t have a clue about it. And even if they did, the last thing Whites were about to do was reshuffle the stacked deck Blacks had been dealt. Elliott’s solution was to teach children, kids as young as eight years old, the damage that Whites imparted every day to Blacks. And the best approach was to follow Lloyd Jennison’s “Indian” maxim: to walk a mile in someone else’s moccasins.

Hundreds of viewers wrote letters saying Elliott’s work appalled them. “How dare you try this cruel experiment out on White children,” one said. “Black children grow up accustomed to such behavior, but White children, there’s no way they could possibly understand it. It’s cruel to White children and will cause them great psychological damage.” Elliott replied, “Why are we so worried about the fragile egos of White children who experience a couple of hours of made-up racism one day when Blacks experience real racism every day of their lives?”

The people of Riceville did not exactly welcome Elliott home from New York with a hayride. Looking back, I think part of the problem was that, like the residents of other small midwestern towns I’ve covered, many in Riceville felt that calling attention to oneself was poor manners and that Elliott had shone a bright light not just on herself but on Riceville; people all over the United States would think Riceville was full of bigots. Some residents were furious.

Through persistence, diligence, and perhaps worst of all, in the eyes of Riceville, sheer ambition, Elliott had catapulted herself to immortality. Regarded, respected, revered. Outside Riceville, she was a visionary, a combination of Rosa Parks, Eleanor Roosevelt, and maybe even Joan of Arc. Inside, she was a con artist. Elliott hated the values that some Riceville parents had instilled in their children. Elliott seemed to know what these young children would grow up to become—unless she imprinted her wisdom on their squishy, developing brains. Elliott’s mission was to administer a mind-altering social-experiment inoculation, even though neither the kids nor their parents had asked for such a vaccination.

Elliott is nothing if not stubborn. She would conduct the exercise for the nine more years she taught the third grade, and the next eight years she taught seventh and eighth graders before giving up teaching in Riceville, in 1985, largely to conduct the eye-color exercise for groups outside the school.

For a host of reasons, some serendipitous, others calculated, the experiment Elliott popularized in 1968 multiplied at dizzying, geometric speed. It spread to other teachers and school districts across the nation and around the world. Thousands of teachers and trainers would adopt the experiment and try it out on students young and old. During the dawning era of multiculturalism, hundreds of corporations used the experiment on their workers. For some who sat at Elliott’s feet, it changed them for the good. The experiment exposed them to racism and its far-reaching impact. But for others, decades after being tormented by an experiment ostensibly designed to teach about racism, many of her subjects still feel the wallop of Elliott’s smack-them-over-the-head method. For more than a few who experienced it, Elliott’s self-proclaimed exercise turned into a monster experiment.

* * *

For years scholars have evaluated Elliott’s exercise, seeking to determine if it reduces racial prejudice in participants or poses a psychological risk to them. The results are mixed. Two education professors in England, Ivor F. Goodson and Pat Sikes, suggest that Elliott’s experiment was unethical because the participants weren’t informed of its real purpose beforehand. Alan Charles Kors, a professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania, says Elliott’s diversity training is “Orwellian” and singled her out as “the Torquemada of thought reform.” Kors writes that Elliott’s exercise taught “blood-guilt and self-contempt to Whites,” adding that “in her view, nothing has changed in America since the collapse of Reconstruction.” In a similar vein, Linda Seebach, a conservative columnist for the Rocky Mountain News, wrote in 2004 that Elliott was a “disgrace” and described her exercise as “sadistic,” adding, “You would think that any normal person would realize that she had done an evil thing. But not Elliott. She repeated the abuse with subsequent classes, and finally turned it into a fully commercial enterprise.”

Others have praised Elliott’s exercise. In Building Moral Intelligence: The Seven Essential Virtues That Teach Kids to Do the Right Things, educational psychologist Michele Borda says it “teaches our children to counter stereotypes before they become full-fledged, lasting prejudices and to recognize that every human being has the right to be treated with respect.” Amitai Etzioni, a sociologist at George Washington University, says the exercise helps develop character and empathy. And Stanford University psychologist Philip G. Zimbardo writes in his 1979 textbook, Psychology and Life, that Elliott’s “remarkable” experiment tried to show “how easily prejudiced attitudes may be formed and how arbitrary and illogical they can be.” Zimbardo—creator of the also controversial 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment, which was stopped after college student volunteers acting as “guards” humiliated students acting as “prisoners”—says Elliott’s exercise is “more compelling than many done by professional psychologists.”

In 2003, Tracie Stewart, a social psychologist at Kennesaw State University in Atlanta, was the lead author in a study to gauge the efficacy of the blueeyes, brown-eyes experiment. Stewart used as her test case a workshop that Elliott conducted in 2000 with students at Bard College, a small, private undergraduate institution in Annandale-on-Hudson, in New York State. So as not to skew their findings, Stewart and her coinvestigators looked for Bard students who hadn’t heard of the experiment or of Elliott. Once accepted into the workshop, participants signed informed consent forms: “You should be aware that the learning exercise may be a difficult experience for some. Participants will take part in group discussions during which they may be exposed to harsh comments and uncomfortable conditions…. If you have a medical condition that might be aggravated by stressful situations or feel that you should avoid stressful situations at the present time, do not sign up for this project.”

Elliott conducted the experiment, which started early on a Saturday morning and lasted eight hours. She followed her routine, sorting forty-seven participants into a blue-eyed (and green- and hazel-eyed) group and a brown-eyed cohort. The blues were crowded into a small, stuffy room with half the number of chairs as people, while the browns were served a full breakfast in a comfortable setting. Per her drill, Elliott prompted the brown-eyed participants to act rudely toward the other group when the two sections convened. She also gave the brown-eyed students answers to an IQ test she would administer to both groups later that day.

When the two groups merged, Elliott had the blueeyed students, wearing collars, sit in the middle of the room while the brown-eyed group sat on either side as though they were observing the “inferior” group. She proceeded to criticize the blues. She had them stand one at a time and read derogatory passages denigrating blue-eyed people. She scolded their performances. When the browns outscored the blues on the fake IQ test, Elliott amped up her scorn of the blues. She picked a blue-eyed, blond woman for ridicule, announcing to everyone that she wasn’t a natural blonde and likely dyed her hair. To another woman, Elliott commented about her “cute butt” and “bedroom voice.” All the while, she encouraged the brown-eyed students to join in on the hectoring. The insults got so intense that two blueeyed students started to cry. One got up and left.

The two groups broke for lunch, returned to debrief, watched the 1970 ABC video “Eye of the Storm,” ate hors d’oeuvres together in the late afternoon, and then left, the experiment officially over. During the next four to six weeks, both groups were assessed by Stewart and her colleagues to see if the experiment had made any impact on their self-awareness of prejudice and racism.

The results were decidedly mixed. The responses from the students mirrored what participants in the U.S. West pluralism workshops in the 1980s had said. They noted a multitude of insults and pain shared by the participants, but minimal change in attitude. Among the student reactions:

“As a Blue Eyes, I was uncomfortable and on edge. I found myself easily angered by anything Jane Elliott said. I felt frustrated and helpless to stop her charade (she was good at her job).”

“I feel some of it was unethical, however, there were so many positive responses I can only believe that the positive outweighs the negatives…. I’ve had a few nightmares, but this is typical…”

“Makes people upset; doesn’t change much; too negative for me.”

“I felt emotionally low after the experiment [exercise]. I wanted to try to forget some of the things that were said or done on the day of the experiment, but I guess that’s what made it so effective.”

Stewart’s thoughts today about the experiment are “proceed with caution.” She said that the experiment may have a positive impact on reducing negative racial attitudes “in the short term,” but any long-term benefits are negligible. Stewart no longer shows videos of Elliott in her undergraduate psychology classes because “there tends to be a greater focus on Jane Elliott herself than the issue of institutional racism.”

A larger, systematic review, published in 2009, that assessed the effectiveness of scores of anti-bias workshops and experiments summarily suggested that further study was needed. “We conclude that the casual effects of many widespread prejudice-reduction interventions, such as workplace diversity training and media campaigns, remain unknown. Although some intergroup contact and cooperation interventions appear promising, a much more rigorous and broad-ranging empirical assessment of prejudice reduction strategies is needed to determine what works.” In other words, the social scientists weren’t able to say that any crash course to modify racial prejudice works.

* * *

Today, teachers still readily employ the blue-eyes, brown-eyes experiment. For many, it is an inspired and clever way to introduce the concept of discrimination and race to youngsters.

In 2009, Elliott took the experiment to Great Britain, where she performed it for a television documentary called The Event in London. There, the thirty participants were adults. Following her script, Elliott threw profanity-laced insults at the collared “inferior” group of blue-eyed participants. As during the experiment’s last iteration on The Oprah Show, the experiment imploded. Many of the UK participants refused to tolerate Elliott’s bullying and walked out.

The show hired two psychologists to stand in the wings during the experiment in case anyone needed intervention, as well as to provide a sports-style playby- play commentary for viewers at home. One was Dominic Abrams, a professor of social psychology at the University of Kent, who today, more than a decade later, doesn’t quite know what to think of Elliott or what she did. “She is a very strong personality and did not appear to treat challenge as anything other than a battle to be won. She certainly had no desire to engage with me as a psychologist (or indeed as a person), so other than her brusque manner toward myself and the production team (which may have been partly an extension of her character part for the day), it was difficult to gain a sense of what she might have been thinking or intending,” Abrams wrote in an email.

Guardian journalist Andrew Anthony was less sanguine. Writing about the British iteration of the experiment, Anthony noted, “Nowadays, grey-haired and mean-eyed, she’s honed her shtick to that of a drill sergeant or prison commandant. She describes herself as the ‘resident bitch for the day,’ and speaks to the blue-eyed contingent as though they were criminally stupid or stupidly criminal. ‘Keep your fucking mouth shut,’ she tells one smiling blue-eyed young man. ‘I don’t play second banana.’ The performance suggests someone who would be a natural in a Maoist re-education camp: self-righteous, vindictive and unswervingly convinced of her case.”

Anthony concluded that Elliott was “more excited by White fear than she is by Black success.”

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 27.3

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Download our app

Elliott defends her work as a mother defends her child. “You have to put the exercise in the context of the rest of the year. Yes, that day was tough. Yes, the children felt angry, hurt, betrayed. But they returned to a better place—unlike a child of color, who gets abused every day, and never has the ability to find him or herself in a nurturing classroom environment.” As for the criticism that the exercise encourages children to distrust authority figures—the teacher lies, then recants the lies and maintains they were justified because of a greater good—she says she worked hard to rebuild her students’ trust. The exercise is “an inoculation against racism,” she says. “We give our children shots to inoculate them against polio and smallpox, to protect them against the realities in the future. There are risks to those inoculations, too, but we determine that those risks are worth taking.”

* * *

Elliott remains as sharp-tongued, contrary, resolute, and opinionated as ever. She has updated her lectures to include a range of contemporary issues: the concept of race (“There’s only one race, the human race”); the Black Lives Matter movement (“It’s insane what we’ve been doing to people of color for the last 250 years”), White supremacists (“They’re coming out of the woodwork”), persistent women (“‘Bitch’ is an acronym for ‘Being in Total Control, Honey’”), former President Trump (“He is basing his political philosophy on writings of Adolf Hitler”), racism among White evangelicals (“Jesus did not look like the little Pillsbury Doughboy”), and oppression of Native Americans (“We call Native Americans ‘savages’ but it was Whites who killed them and stole their lands”). Her most recent lectures mention COVID-19, as well as the LGBTQ and Latinx communities. Elliott hasn’t given up her interest in public education, which is at the center of any presentation she gives (“We could destroy racism in two generations by changing what is taught in classrooms all over the United States, but first we’d have to change the level of racism among the teachers”).

For decades, Elliott has issued sweeping generalizations, including her oft-repeated declaration that all Whites in America are racists. “If you are looking at a White person who was born, reared, and schooled in the United States, then you are looking at a racist,” she told an audience at the University of Northern Colorado as far back as 1993. “Blacks aren’t racist; they are only reacting to the actions of Whites.”

Elliott often refers to herself as “a faded Black person.” When she spoke with actress Jada Pinkett Smith on her Facebook Watch show, Red Table Talk, in 2018, she said, “My people moved far from the Equator and that’s the only reason my skin is lighter. That’s all any White person is.” She concedes that as a White woman speaking about how some Black people might feel, she may be guilty of accusations that she’s a charlatan and a poseur. “There are those Blacks who ask me what a White woman like me is doing talking about their experience, since I can’t possibly know what it’s like to walk in their shoes. Sometimes I’m accused of just running another White woman’s game. Those are valid criticisms.”

What truly motivated Elliott to introduce an experiment to a roomful of third graders and to make two days last more than five decades? Perhaps she was seeking an exit from what she envisioned would be her own humdrum life. She had something personal to prove, a game of one-upmanship amid a landlocked sea of naysayers who had looked down on her ever since she’d been born. What was it about her that seemed to require that she push the limits, shocking everyone—starting with children? Was it to make up for the shortcomings the locals had assigned her? Was it to make her father proud? Was it to get back at the locals and their sense of what it meant to be successful, particularly as a woman? Was it to show the other teachers in the chatty teachers’ lounge how horribly wrong they were?

Classroom No. 10 was way too small for Elliott. Her dream was to teach everyone. ![]()

Based on the author’s 2021 book Blue Eyes, Brown Eyes: A Cautionary Tale of Race and Brutality, published by University of California Press, excerpted with permission. © 2021 by Stephen G. Bloom

About the Author

Stephen G. Bloom is a professor of journalism at the University of Iowa and author of six nonfiction books: Postville; Inside the Writer’s Mind; Tears of Mermaids; The Oxford Project; The Audacity of Inez Burns; and Blue Eyes, Brown Eyes.

Stephen Bloom on The Michael Shermer Show

Listen to Michael Shermer’s conversation with Stephen Bloom exploring the never-before-told true story of Jane Elliott and the “Blue-Eyes, Brown-Eyes Experiment” she made world-famous, using eye color to simulate racism. Shermer and Bloom discuss: Jane Elliott and how she came to conduct her famous experiment • reactions to it (in the classroom, locally, nationally, internationally) • whether the “experiment” was really more of a demonstration • public interest, from Johnny Carson to Oprah Winfrey • the questionable ethics of the experiment • what it reveals about tribalism, racism, obedience to authority, role playing, social proof • whether the experiment reveals hidden racist attitudes or creates them in children • Does it indicate bad apples or bad barrels? • race sensitivity training programs, then and now (and why they don’t really work) • what drives moral progress • the future of journalism.

This article was published on November 22, 2022.