In 2022 it’s hard to decide which is the craziest conspiracy theory people believe. Among chemtrails, QAnon, rigged election, and vaccine conspiracies, flat Earth (F.E.) beliefs surely belong at or near the top. Why? The other conspiracy beliefs have at their core a tiny, tiny bit of physical plausibility. It is possible to spray chemicals into the air from aircraft. It is possible to steal elections, eat children and engage in disgusting sexual activity. It is possible to inject harmful substances. None of these beliefs directly violate physical reality. However, there is no possibility of a flat planet.

Investigative journalist Kelly Weill’s important book details her investigation of the flat Earth movement, the people involved, and their psychology. That movement is more bizarre and interesting than I, at least, had any idea. Before reading this book, I had thought that the F.E. movement was just a bunch of people who thought that Earth was flat and left it at that. I was wrong. An important point of the book is that the F.E. movement contains a great diversity of flat Earth beliefs. As an example, an obvious question is why don’t we find an edge? Well, some say, there is an edge—it’s the Antarctic which forms an ice wall around the flat Earth to keep the oceans from spilling over the edge. But regular people can’t go there to see the edge because it’s highly guarded by secret international troops. Other flat Earth believers say that there is no edge, and that Earth is flat and goes on forever.

What about other planets? Are they flat too? One individual Weill quotes replied to a question from Elon Musk as to whether Mars is flat by saying “no” because “Mars has been observed to be round” (p. 207). By this, one assumes that “round” means spherical because in F.E. belief a planet could be both flat and round. Or flat and square. Or flat and shaped like a great big New Hampshire. Others do not believe in outer space but that the Sun and stars are on a dome high up in the sky, harkening back to medieval beliefs. More disturbingly, Weill documents the recent development of an overlap between the F.E. movement and QAnon and similar conspiracy theory groups.

Despite the diversity of F.E. beliefs, there is a common theme that runs through the movement. Specifically, that “governments and scientists are actually peddling a ‘global lie’ in order to control the world by tarnishing religious teachings or by making people feel insignificant next to the great expanse of outer space” (p. 3). Those in the movement have a willingness or desire to seek out conspiracies and an ability to immerse themselves in their own particular conspiracy-believing milieu to the extent that evidence contrary to their beliefs is rejected out of hand as due to hoaxes (e.g., the moon landings, anything from NASA) or to an explicit governmental coverup.

The idea that Earth is spherical dates back to at least the writings of Pythagoras in the 6th century BCE. Weill gives a good history of the F.E. movement in the English-speaking world, and debunks the myth that when Columbus sailed west his crew was terrified of falling off the edge of a flat Earth. In the first chapter Weill describes the start of the modern flat Earth movement. The main character here is an English socialist named Samuel Birley Rowbotham.

In the late 1830s he was deeply involved in a failed utopian community. He’s famous in flat Earth circles because of experiments he claimed to have performed in a long straight canal in Bedford, England. It had been known for centuries that as a ship sailed away a viewer would see the ship both get smaller and the lower parts of the ship disappear before the upper parts did, due to the curvature of the planet. Rowbotham claimed that when he stood in the middle of the Bedford Canal ships got smaller as they moved away but he did not see the lower parts vanish sooner than the upper parts. This, he argued, showed that Earth was flat. His claim is still offered as proof that Earth isn’t spherical.

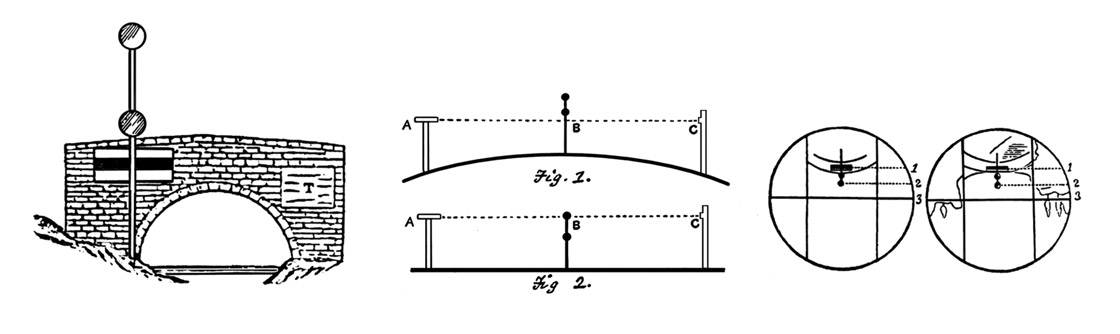

In fact, as the co-discoverer of natural selection (with Charles Darwin), Alfred Russel Wallace demonstrated in a bet with a flat Earth advocate named John Hampden at that same canal, in which he set up three objects—a telescope, a disc, and a black band—along a six-mile stretch such that “if the surface of the water is a perfectly straight line for the six miles, then the three objects…being all exactly the same height above the water, the disc would be seen in the telescope projected upon the black band; whereas, if the six-mile surface of the water is convexly curved, then the top disc would appear to be decidedly higher than the black band, the amount due to the known size of the earth.” As the diagram (below) shows, Wallace’s experiment clearly “proved that the curvature was very nearly of the amount calculated from the known dimensions of the earth.” Predictably, Hampden refused to even look through the telescope.

View through the level used by Alfred Russel Wallace in the “Bedford Level” survey experiment: a wager between him and John Hampden to demonstrate the curvature of the earth. Diagram printed in The Field (March 26, 1870), and reproduced in Wallace’s autobiography.

In Chapter 2 we learn about the town of Zion, Illinois, founded in 1901 by John Dowie, a faith-healing preacher from Scotland. In 1906 one of Dowie’s associates, Wilbur Glenn Voliva, pretty much took over the town from Dowie. Volvia believed that there “was no such thing as gravity” (p. 43). Volvia saw to it that F.E. theory was taught in the Zion public schools until the early 1930s when his candidates lost elective office. The story of Zion is fascinating, amusing, and well told.

The next several chapters chronicle the development of the modern F.E. movement from being a “Joke” (Chapter 3) to its current entwinement with conspiracy theories of all sorts. Another chapter is devoted to Mike Hughes, the flat earther (but was he, really?) rocket man who wanted to find out for himself if Earth was spherical. Not trusting NASA, the airlines, and other such sources, his plan was to build a rocket that would take him high enough so he could see for himself the curvature of the planet, if there was any. He did successfully build and ride several rockets, but they didn’t go high enough. On February 22, 2020 Hughes climbed aboard a rocket more powerful than any he had used before. It malfunctioned rather spectacularly (you can see it on YouTube), and he was killed instantly.

Weill has been studying the F.E. movement for years. Like any good investigative reporter, she has gone to F.E. conferences and hung out with and gotten to know many F.E. believers personally. It’s clear from her writing that she finds them fascinating and generally good, if seriously misguided, people. She knew Hughes personally and was very saddened by his death. The last chapter, “Away from the Edge,” describes the role that the internet, and specifically social media platforms such as Facebook and YouTube, have played in increasing the popularity of not only F.E. belief but also conspiracy theories in general.

Weill outlines in detail how the algorithms used by these companies were responsible for guiding people toward F.E. and other conspiracy theory websites and videos when they did not start out looking for any such information. The fixes now in place to correct these problems are not all that effective. There is much food for thought in this chapter.

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 27.4

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Download our app

Like most readers of Skeptic, I suspect that five years ago I would have dismissed F.E. belief as nothing but a joke. Weill makes it clear that this is not the case. Yet after finishing the book, I was left with a feeling of non-completeness. Something was missing. Weill’s description, in the final chapter, of how the internet facilitates F.E. belief is all well and good and, as far as it goes, accurate. Still, I was left wondering how normal, intelligent people could accept a belief that is so obviously wrong and for which, as noted above, there is no possible referent for a flat planet in the real universe.

As I finished the book, I thought of Susan Clancy’s 2007 book Abducted, which approached the alien abduction movement in much the same way as Weill deals with the flat Earth movement. By the end of Clancy’s book, along with other research, the reader has a good explanation of alien abduction belief—hypnopompic hallucinations combined with a fantasy-prone personality. It is no fault of Weill that, at this point, there is no similar compelling explanation for F.E. beliefs, although it would be very interesting to see if flat Earth believers, and conspiracy theory believers in general, score higher on fantasy proneness tests than controls. ![]()

About the Author

Terence Hines is a cognitive neuroscientist and professor at the Psychology Department, Pace University, Pleasantville, NY and adjunct professor of neurology at New York Medical College in Valhalla, NY. His research focuses on paranormal belief, the cognitive representation of number and, when he has time, the nature of bilingual memory. He is the author of Pseudoscience and the Paranormal. He received his undergraduate education at Duke University and his PhD from the University of Oregon.

This article was published on February 28, 2023.