“David Irving’s three-year prison sentence for denying the Holocaust may please his detractors, but it is an assault on the civil liberties of us all.” – Michael Shermer

In this week’s eSkeptic, we reprint Michael Shermer’s opinion editorial which first appeared in the Los Angeles Times on February 22nd, 2006.

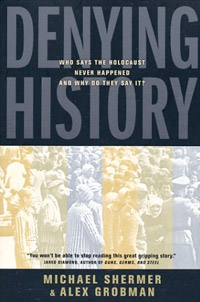

Michael Shermer is the publisher of Skeptic magazine, a monthly columnist for Scientific American, and the author of Denying History: Who Says the Holocaust Never Happened and Why Do They Say It? (University of California Press, 2002, ISBN 0520234693).

Readers may also want to check out Michael Shermer’s article entitled, “Enigma: The Faustian Bargain of David Irving,” which appeared in eSkeptic for Tuesday, May 3rd, 2005.

Giving the Devil His Due

by Michael Shermer

“More women died in the back seat of Edward Kennedy’s car at Chappaquiddick than ever died in a gas chamber at Auschwitz.”

David Irving, July 2003 (photo courtesy of Focal Point Publications)

Is this line more offensive to Jews than an editorial cartoon depicting the prophet Muhammad with a turban bomb is to Muslims?

Apparently it is, because the editorial cartoonists are still free, whereas the man who made this statement — British author David Irving — was sentenced February 20 to three years in an Austrian jail for violating an Austrian law that says it is a crime if a person “denies, grossly trivializes, approves or seeks to justify the National Socialist genocide or other national socialist crimes against humanity.”

Irving had traveled to Austria in November, 2005 to deliver a lecture to a far-right student fraternity, but was arrested on a warrant dating back to 1989, when he gave a speech and interview denying the existence of gas chambers at Auschwitz. After pleading guilty to the charge, Irving told the court, “I made a mistake when I said there were no gas chambers at Auschwitz,” and “The Nazis did murder millions of Jews.”

That David Irving has been, and probably still is, a Holocaust denier is indisputable. In 1994 I interviewed him for a book on Holocaust denial, and he told me then that no more than half a million Jews died during the Second World War, and most of those due to disease and starvation. Irving also added that Hitler was the Jews’ best friend: “Without Hitler, the State of Israel probably would not exist today so to that extent he was probably the Jews’ greatest friend.” In 2000, the judge in his libel trial in England called him “an active Holocaust denier … anti-Semitic and racist.” And in April, 2005, I attended a lecture Irving gave in Costa Mesa at an event sponsored by the Institute for Historical Review, the leading voice of Holocaust denial in America, where he joked about the Chappaquiddick line and, holding his right arm up, boasted, “This hand has shaken more hands that shook Hitler’s hand than anyone else in the world.”

The important question here is not whether Irving is a Holocaust denier (he is), or whether he offends people with what he says (he does), but why anyone, anywhere should be imprisoned for expressing dissenting views or saying offensive things. Today, you may be imprisoned or fined for dissenting from the accepted Holocaust history in the following countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Israel, Lithuania, New Zealand, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Switzerland.

Given their disastrous history of being too lenient with fringe political ideologues, it is perhaps understandable that countries like Germany and Austria have sought to crack down on rabble-rousers whose “hate speech” can and has led to violence and pogroms. In some cases, the slippery slope has only a few paces between calling the Holocaust a “Zionist lie” to the neo-Nazi desecration of Jewish property.

And as we have witnessed repeatedly, Europeans have a different history and culture of free speech than we do in this country. In Germany, for example, the “Auschwitz-Lie” Law, makes it a crime to “defame the memory of the dead.” In May of 1992, Irving told a German audience that the reconstructed gas chamber at Auschwitz I was “a fake built after the war.” (It is, in fact, a post-war reconstruction made by the Soviets running the camp museum.) The following month when he landed in Rome, he was surrounded by police and put on the next plane to Munich where he was fined 3,000DM. Irving appealed the conviction but it was upheld and the fine increased to 30,000DM (about $20,000) after he publicly called the judge a “senile, alcoholic cretin.”

In England, libel law requires the defendant to prove that he or she did not libel the plaintiff, unlike U.S. law that puts the onus on the plaintiff to prove damage, and they recently debated the merits of banning religious hate speech. In France, it is illegal to challenge the existence of the “crimes against humanity” as they were defined by the Military Tribunal at Nuremberg; and another law, on the books until just a few weeks ago, required that France’s colonial history (which was not always “humane”) has to be taught in a “positive” light.

In the traditionally liberal Canada there are “anti-hate” statutes and laws against spreading “false news.” In late 1992, Irving went to Canada to receive the George Orwell award from a conservative free speech organization, whereupon he was arrested by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, led away in handcuffs, and deported on the grounds that his German conviction made him a likely candidate for future hate speech violations.

Even in the land of Thomas Jefferson and the First Amendment, freedom of speech does not always ring. On Friday, February 3, 1995, Irving was invited by the Berkeley Coalition for Free Speech to lecture at the University of California, Berkeley. More than 300 protesters surrounded the hall and prevented Irving and the 113 ticket holders from entering. (That, however, is quite different from passing a law to bar him from speaking.)

Austria’s treatment of Irving as a political dissident should offend the same people who defend the rights of political cartoonists to express their opinion of Islamic terrorists, and of the civil libertarians who leapt to the defense of the University of Colorado Professor Ward Churchill when he exercised his right to call the victims of 9/11 “little Eichmanns.” Why doesn’t it? Why aren’t freedom lovers everywhere offended by Irving’s conviction?

Freedom is a principle that must be applied indiscriminately. We have to defend David Irving in order to defend ourselves. My freedoms are inextricably tied to Irving’s freedoms. Once the laws are in place to jail dissidents of Holocaust history, what’s to stop them from spreading to dissenters of religious or political histories, or to skepticism of any sort that deviates from the accepted canon?

No one should be required to facilitate the expression of Holocaust denial, but neither should there be what the U.S. Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis called the “silence coerced by law — the argument of force in its worst form.” The point was poignantly made in Robert Bolt’s play, “A Man for All Seasons,” in which William Roper and Sir Thomas More debate the relative balance between evil and freedom (Act 1, Scene 6):

Roper: So now you’d give the Devil benefit of law.

More: Yes. What would you do? Cut a great road through the law to get after the Devil?

Roper: I’d cut down every law in England to do that.

More: Oh? And when the law was down — and the Devil turned round on you — where would you hide? Yes, I’d give the Devil benefit of law, for my own safety’s sake.

Call David Irving the devil if you like — the principle of free speech gives you the right to do so. But we must give the devil his due. Let David Irving go, for our own safety’s sake.

Post Script

on Irving & the Eichmann Papers

In the Austrian trial Irving admitted that he denied the Holocaust in 1989, telling the court: “I said that then based on my knowledge at the time, but by 1991 when I came across the Eichmann papers, I wasn’t saying that anymore and I wouldn’t say that now. The Nazis did murder millions of Jews.”

Not quite. While researching my book, Denying History, Irving told me the story about the Eichmann papers. Here is what actually happened. Witness one of the greatest rationalizations in the history of historiography.

Adolf Eichmann was one of the prime architects of the Final Solution. In 1991 David Irving was on a lecture tour in Argentina. Immediately following a lecture, Irving explained, “a guy came out to me with a brown-paper package. And he said, ‘You’re obviously the correct repository for these papers that we’ve been looking after since 1960 for the Eichmann family.’ See, the Eichmann family panicked when he was kidnapped in the streets. And they took all his private papers which they could find, that had any kind of bearing, put them into brown paper and gave them to a friend. Then he gave them to this man who gave them to me, who gave them to the German government.”

In the manuscript, Irving explains, Eichmann “refers on many occasions to a discussion he had with Heydrich at the end of September or October, 1941, in which Heydrich says, in quotation marks, these two lines: ‘I come from the Reichführer [Himmler]. He has received orders from the Führer for the physical destruction of the Jews.’”

It could not be any clearer than that, right? Wrong. A master rhetorician like Irving can spin-doctor any potentially damaging document. While admitting that “it rocked me back on my heels frankly because I thought ‘Oops!’,” he recovered in time to “tell myself, ‘Don’t be knocked off your feet by this one.’” The easy solution was to announce that the Eichmann memoirs was a fake, but this would appear to contradict the verdict of the German Federal Archives at Koblenz, who determined that the memoir is authentic.

In 1992, Irving confessed that “Quite clearly this has given me a certain amount of food for thought and I will spend much of this year thinking about it. They show that Eichmann believed there was a Führer order” (Führerbefehl). So, Irving’s initial conclusion hints at intellectual honesty: “It makes me glad I have not adopted the narrow-minded approach that there was no Holocaust.”

As time passed, however, Irving found his out. The memoirs are real, but Eichmann lied about the Führerbefehl. Why? As he told the journalist Ron Rosenbaum in an elaborate rationalization, during the Suez crisis in 1956 Eichmann worried that if Israel conquered Cairo they might intercept intelligence files on fugitive Nazis in South America, possibly leading to his capture and arrest. Irving picks up the story (from his imagination, of course):

Eichmann must have had sleepless nights, wondering what he’s going to do, what he’s going to say to get off the hook. And though he’s not consciously doing it, I think his brain is probably rationalizing in the background, trying to find alibis. The alibi that would have been useful to him in his own fevered mind would be if he could say that Hitler — all he did was carry out [Hitler’s] orders.

Eichmann, Irving speculates, inserted into his memoirs the phrase “Der Führer hat richt der Ausrottung der Juden befohlen” — “The Führer has ordered the extermination of the Jews” — so that if he were ever captured his defense would be that he was merely following orders. Eichmann was, of course, captured and tried, and his defense included this argument, along with a moral equivalency one where all sides in the war were equally guilty of atrocities. The defense worked about as well as it did at Nuremberg — Eichmann was executed.

Got your Gear?

Skeptics t-shirts

Skeptics Society T-shirts, black with white lettering, are available in one of two different designs. “Skeptics Society, Skeptic.com” (on the front) and your choice of “Science Rules” or “Got Skeptic?” (on the back).

The Bridge to Humanity

How Affect Hunger Trumps the Selfish Gene

with Dr. Walter Goldschmidt

Sunday, March 12th, 2006

Baxter Lecture Hall

Caltech, Pasadena, CA

Anthropologist Walter Goldschmidt argues that culture is the product of deep biological mechanisms that came into being by an evolutionary process. Central to Dr. Goldschmidt’s thesis is the recognition of the separate evolutionary origin of what we call love: sexual and nurturant. These ancient heritages demand very different forms of behavior; one essentially competitive and the other concerned with mutuality. Underlying nurturance is the phenomenon of “affect hunger,” an urge to seek the affection that is needed for the proper development of the neurological system in humans and other social mammals. Goldschmidt shows that affect hunger not only provides a reward system for learning language and other cultural information, but also remains a motive for social behavior throughout life.

Dr. Goldschmidt is Professor Emeritus at UCLA in both Anthropology and Psychiatry. He is the author of The Human Career, Exploring the Ways of Mankind, As You Sow, The Sebei, and Comparative Functionalism. He has served as editor of American Anthropologist, Ethos, Journal for the Society of Psychological Anthropology, and was president of the American Anthropological Association.