photo: Irving with posters.

Enigma:

The Faustian Bargain of David Irving

by Michael Shermer

When I was a graduate student in a doctoral program in history at Claremont Graduate School in the late 1980s, our German historian called our attention to an emerging “Historikerstreit” among his colleagues on the continent. There is nothing more revealing about character and conscience than a good intellectual brouhaha.

In the 1950s, conservative German historians more concerned with the threat of Communism than with moribund Nazism tended to demonize Hitler, repudiate the Nazis, and portray National Socialism as an historical aberration. In the 1960s and 1970s, liberal German historians explored the social and economic forces that led Weimar Germany into the arms of the Nazis, and were more inclined to accept culpability for Nazi war crimes. In the 1980s, neo-conservative historians rejected the liberal focus on the German “burden of guilt,” tended to downplay the exceptionality of the Holocaust, pointed out Stalin’s equally deadly genocides, and suggested that historians focus instead on the origins of the Cold War. (Recall the ruckus over President Ronald Reagan’s plan to lay a wreath in a military ceremony at the Bitburg cemetery that contained the graves of Wehrmacht and Waffen SS soldiers.) In response, and thus setting off the Historikerstreit, liberal historians attacked the new conservatives as “revisionists,” especially those historians who made the Hitler-Stalin equivalency argument. The conservatives countered that, in fact, the Third Reich was engaged i n two wars: the unfortunate bad war against England and the United States that should have never been fought, and the necessary good war against the Soviet Union and Communism that had to be fought to secure a Pax Europa.

The Historikerstreit was just the latest in a series of struggles to come to grips with a regime that in the end appears to have had few redeeming features. As the German historian Joachim Fest wrote in concluding Inside Hitler’s Bunker: The Last Days of the Third Reich, upon which the remarkable film Downfall was based:

What makes Hitler a phenomenon unlike any other in history is that his goals included absolutely no civilizing ideas. Despite their obvious differences, conquering world powers—ancient Rome, the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, Napoleon’s France, and the British Empire—have all held out some promise to humanity, no matter how vaguely defined, relating to peace, progress, or freedom. In this way they received a certain exoneration from history, and in the end were often acquitted of charges that greed and thirst for glory were the major motives in their attempts to subjugate other peoples. Hitler , on the other hand, as he conquered territory and extended his control, rejected all idealistic trimmings, deeming them unnecessary to disguise his claim to power.

Indeed, Downfall strikingly portrays the cult of death that surrounded the Nazis in the final days of the war, and I came out of that film with a paradoxically odd sense of despair that there really was nothing of value to be gleaned from the Nazi social experiment, other than it failed utterly. It helped put into perspective the Historikerstreit, and the motivations of those seeking to make sense of this seemingly senseless historical paroxysm. It also gave me additional insight into the strange case of David Irving, one of the foremost historians of Nazis, and the quixotic movement of Holocaust revisionism, which I have been tracking for over a decade. (We devoted an entire issue of Skeptic magazine in 1994 to the movement and its arguments, Vol. 2, No. 4, and I wrote a book on the subject, Denying History, published in 2000 by the University of California Press.)

Although he resides in London, Irving periodically tours America giving lectures and signing books for smallish audiences in hotels whose location is only disclosed to those known to the author or his hosts. I had not seen or spoken to Irving in several years, so it was with some anticipation that I and a friend made the trek to Orange County on Sunday night, April 17, to hear him speak on “The Faking of Adolf Hitler for History,” and to regale his audience with his latest battles with “the traditional enemy” (AKA “the Jews”). The event was sponsored by the Institute for Historical Review (IHR), the leading voice of Holocaust revisionism, and Irving was introduced by IHR Director Mark Weber. There were about 60 people in attendance, the demographics of which matched those of prior meetings I have attended—mostly old white guys complaining about the world, especially Israel, the “Zionist lobby,” and “the Jews.”

photo: Mark Weber lecturing.

Before introducing their celebrity hero, however, Weber delivered a lecture on the same topic as that advertised for Irving, which went on for nearly an hour, and was followed by a lengthy Q & A and a break. My friend and I settled in for what was going to be a long evening. On the drive to the hotel I offered my friend a brief history of Holocaust revisionism, the leading characters and their motives, but wondered if, in the interim, the movement had shifted focus. It hadn’t, and Weber did not disappoint.

In August of 1945, Weber began, the future U.S. President John Kennedy visited Berchtesgaden, Hitler’s Bavarian retreat, and wrote in his diary that Adolf Hitler would emerge from history as having the stuff of which legends are made. Kennedy was right, Weber continued, Hitler was a legendary leader, but his legitimate reputation is being restrained from coming to the forefront. Restrained by whom? Well, in part, Weber confessed, Hitler did make a number of mistakes that cost him the war, and as we all know, history is written by the winners. But this does not explain the reputation Hitler still retains 60 years after the fall of the Third Reich. After all, other great statesmen in history blundered and led their nations into ruin, but they are not vilified to the extent that Hitler has been in our time. Something else is at work here.

Lies are being told about Hitler, Weber explained. Dictionaries and encyclopedias describe Hitler as a madman and dictator who wanted to take over the world. In fact, Weber explained, it was Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin who wanted to control the world. While Hitler was attempting to build an alliance with the United States and England in the late 1930s, Churchill and Roosevelt were doing everything in their power to nudge their respective countries into war with Germany. The German people openly adored their Führer; Austrians accepted unification with Germany with open arms; both Germany and Austria prospered economically and socially under National Socialism; even the one-time British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, after visiting Germany in 1936, praised the work of Hitler and described him in glowing terms as a unifier of the German people and a savior of the German economy.

So why are we not getting a fair and balanced view of Adolf Hitler? Weber’s answer was as unequivocal as it was predictable: Jewish and Zionist organizations have purposefully painted a portrait of Hitler as a Satanic force of pure evil, preventing us from seeing Hitler as he really was: a great statesman who made some mistakes. But in the long run even the Jews will not be able to hold back the changing tides, Weber concluded optimistically. In Turkey, for example, Mein Kampf has recently emerged as a bestseller. Why? Because the Turkish people, like so many others around the globe, are turning to Hitler and his philosophy as a viable option to the other failed choices. According to Weber, the 20th century saw the domination of four political systems: Communism, theocracy, liberal democracy, and National Socialism. Communism is dead. Theocracies are archaic. Liberal democracy, with the decline of America’s reputation in the global community, is rapidly falling out of favor. That leaves National Socialism.

In any other venue a lecture such as this would have been met with gaping stares of disbelief; Weber was rewarded with enthusiastic applause and a round of questions.

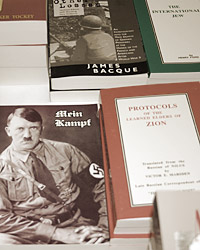

photo: Books for sale at the event.

On the break those who wanted to learn more about Hitler, the Nazis, and the Jews could do so at the IHR book table, where such classics as Mein Kampf, The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, and Henry Ford’s The Eternal Jew could be purchased for modest sums.

While I was snapping a few digital photos on the break David Irving recognized me and suggested we step outside for some fresh air. He was, as I remembered him to be, warm and friendly, charming and witty, even though his girth had widened a bit along with the graying of his thick mop of hair. He queried: “Are you here because you are becoming more revisionist, or are you an objectivist like me?” It was a rhetorical question meant to distance himself from his host and audience—Irving, as his web site and literature attest, believes in “Real History” based strictly on the archival facts. He then recounted his recent experience with American authorities, who had apparently been alerted to his visit by British Airways via a security dossier. I must have had a disconcerting expression on my face because Irving then retorted, with that wry British wit and half smile: “Of course, I don’t object to British Airways doing this, as this is the least one would expect from a proper security service. I don’t mind people spying on me as long as they are the Good Guys. It’s the Bad Guys I object to.” The reference needed no further explication.

Irving opened with an unsurprising disclaimer: “I am not a Holocaust denier.” But considering his audience it was weirdly ironic that he then said: “I am a Holocaust survivor.” Over the years I have heard David Irving make many surprising statements, but this one really made me sit up. “This should be interesting,” I thought . Since the Jews did not suffer any more than many other people did during the Second World War, Irving explained, there were lots of Holocaust survivors, chief among them German civilians at Hamburg and Dresden; but even in England people suffered, including him where, as a young boy, he was deprived of many of life’s essentials in the early 1940s.

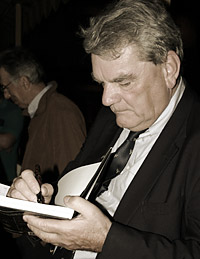

photo: Irving signing a book.

Irving’s extemporaneous lecture continued with parenthetical asides ranging across the spectrum from Hitler and Churchill to his own childhood and current battles with Jewish and Zionist forces. We’ve all seen the films from the concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen, Irving segued, which show allied soldiers bulldozing hundreds of emaciated bodies into open-pit graves. Is it possible, Irving inquired rhetorically, that these prisoners were looked after properly until the allies’ mass bombing raids destroyed the railway lines that brought supplies to the camp? Speaking of exterminating masses of innocent people, Irving continued, what about the victims at Dresden? A German judge, he said, just ruled that what the allies did to the German people in that city could be called a “holocaust.”

“Conformist historians,” Irving reflected, blindly mirror the received wisdom, incestuously citing each other’s secondary works. “We non-conformist historians go straight to the primary sources,” he boasted, regaling us with breathless tales of his encounters with Nazi archives and even old Nazis who knew and worked with Hitler. “This hand,” Irving proclaimed with high drama as he held up his right arm, “has shaken more hands that shook Hitler’s hand than anyone else in the world.”

It was a statement that only an enigma like David Irving could make that would not draw looks of utter incredulity. This is, after all, the man who told a Calgary, Canada audience in September of 1991 that “more women died in the back seat of Edward Kennedy’s car at Chappaquiddick than ever died in a gas chamber at Auschwitz.” If it were not for the gravitas of its implications the line would evoke laughter. What is it about David Irving that keeps him in the news? The enigma emerges from the fact that he is, at one and the same time, brilliant and bellicose, deviously clever and devilishly deceptive—a man who “coulda’ been a contenda” but instead morphed into a pretender.

Many professional historians recognize Irving’s talents. An elder statesman of German historians, Hans Mommsen, for example, wrote of him in 1978: “It is our good fortune to have an Irving. At least he provides fresh stimuli for historians,” an observation that Irving proudly displayed on his website (www.fpp.co.uk) until Mommsen asked him to take it down: “While I still recognize several among your scholarly contributions in the field of Nazi history, although I altogether reject the turn in your judgment with respect to the Holocaust and other aspects, I certainly do not appreciate to get involved in your internet campaign. Hence, I urge you to omit quotations like the utterance made by me in 1978, the context of which is no longer comprehensible for the public.”

Similarly, the British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, who penned the classic work The Last Days of Hitler, once observed: “I regard Irving as a very industrious and efficient investigator, and hunter of documents, a hard worker and good writer. That is on the credit side.” On the debit side, however, Trevor-Roper noted: “But I don’t regard him as an historian. I don’t think he has any historical sense. He is a propagandist who uses efficiently collected and arranged material to support a propagandist line.”

To his credit, Irving includes both positive and negative assessments on his web page, including quotes from Mr. Justice Gray, who presided over Irving’s highly-publicized libel trial in 2000 against Holocaust historian Deborah Lipstadt and her British publisher Penguin books. (Irving claimed that by calling him a “Holocaust denier” Lipstadt and her publisher had damaged his reputation, and thus his livelihood, as an author and historian.) Gray wrote: “As a military historian Irving has much to commend him. For his works of military history Irving has undertaken thorough and painstaking research into the archives. He has discovered and disclosed to historians and others many documents which, but for h is efforts, might have remained unnoticed for years. It was plain from the way in which he conducted his case and dealt with a sustained and penetrating cross-examination that his knowledge of World War Two is unparalleled. His mastery of the detail of the historical documents is remarkable.”

Reading this passage one would be amazed to learn that Gray, in fact, ruled against Irving. His reason for so doing was unequivocal: “The charges which I have found to be substantially true include the charges that Irving has for his own ideological reasons persistently and deliberately misrepresented and manipulated historical evidence; that for the same reasons he has portrayed Hitler in an unwarrantedly favorable light, principally in relation to his attitude towards and responsibility for the treatment of the Jews; that he is an active Holocaust denier; that he is anti-semitic and racist and that he associates with right wing extremists who promote neo-Nazism.”

Some journalists have also given Irving a nod of recognition. The indefatigable Christopher Hitchens, one of the finest essayists of our time, has publicly defended both Irving’s scholarship and freedom to speak and write. “I would not consider as qualified in the argument about Churchill anybody who had not read Irving’s work,” Hitchens wrote in a review of Churchill’s War in the Atlantic Monthly. Elsewhere, Hitchens called St. Martin’s Press “cowardly” for caving in to media pressure to cancel publication of Irving’s Goebbels biography. “One should be allowed to read Mein Kampf as well as Heidegger. Allowed? One should be able to do so without permission from anybody,” Hitchens noted, including Irving’s works in this list of forbidden books which, he added sardonically, one cannot obtain even in the land of the First Amendment. Yet, after Hitchens hosted a private dinner for Irving at his home, his wife (who left the home at the same time as Irving after dinner) “rather gravely asked me if I would mind never inviting him again.” Hitchens explained:

It transpired that, while in the elevator, Irving had looked with approval at my fair-haired, blue-eyed daughter, then five years old, and declaimed the following doggerel about his own little girl, Jessica, who was the same age:

I am a Baby Aryan

Not Jewish or Sectarian;

I have no plans to marry an

Ape or Rastafarian.The thought of Carol and Antonia in a small space with this large beetle-browed man as he spouted that was, well, distinctly creepy.

This little ditty, which Irving had repeated elsewhere, came back to haunt him in his libel trial. Nevertheless, Hitchens gave Irving one more chance to redeem himself with a post-trial lunch, in which he inquired whether Irving had, as reported in the press, slipped up one day by addressing the judge in the trial not as “Your Honor” but as “Mein Führer.” Irving explained that it was a simple misunderstanding in which he was quoting slogans from a German rally at which he had spoken, and he happened to look up at the judge at the wrong moment. But when Hitchens later asked Ian Buruma, a fellow journalist who was reporting on the trial for The New Yorker, to look into the matter, Buruma queried Irving in confidence, who confessed to him: “Actually, I did say it.” In frustration, Hitchens gave up the cause: “At this point I finally decided that anyone joining a Fair Play for Irving Committee was up against a man with some kind of death wish.”

Why does David Irving have a death wish? A little background into the man and his unique pathway in life offers some insights. Irving’s attitudes about the Holocaust have evolved, beginning in 1977 with his $1,000 public challenge to historians to produce the long-sought “Führerbefehl”—the order from Hitler to exterminate the Jews (at this time Irving believed the Holocaust happened but th at Hitler did not order it). The challenge was never met (it was primarily a publicity stunt in conjunction with the publication of Hitler’s War). After reading Fred Leuchter’s The Leuchter Report, which denies the homicidal use of gas chambers, Irving began to deny the Holocaust altogether, not just Hitler’s involvement. Although he disclaims any official affiliation with the IHR (“you will see that my name isn’t on the masthead”), Irving is a regular speaker at IHR conventions and frequently lectures to such groups around the world proving that he is, at the very least, an apologist for Holocaust revisionists, if not for Hitler and the Nazis. In a 1994 interview with me, for example, Irving claimed that Hitler was, in actuality, the Jews’ best friend: “Without Hitler, the State of Israel probably would not exist today so to that extent he was probably the Jews’ greatest friend.”

After Irving testified for the defense in revisionist Ernst Zündel’s 1985 Canadian “free speech” trial, various governments placed criminal charges against him. He has been deported or denied entry into several countries, and his books have been removed from most stores. As he recounts on his web page, his publisher, Focal Point (which Irving founded and operates to print his books), has received notices from bookstores in England canceling distribution of Hitler’s War and other titles. “Following complaints from valued customers we no longer feel able to stock this title,” read one from a Sheffield bookstore in July, 1992. Also in the same year, the director of Media House Publications in Johannesburg, South Africa, informed Irving that with regard to Hitler’s War, “I don’t want any copies on our premises. We have had some incidents already. Many of our book buyers are Jewish. It is much easier for [my staff] now to say, ‘We don’t stock the book.’”

Where Irving goes, trouble follows. In May of 1992, for example, Irving told a German audience that the reconstructed gas chamber at Auschwitz I was “a fake built after the war.” (It is, in fact, a post-war reconstruction made by the Soviets running the camp museum.) The following month when he landed in Rome, he was surrounded by police and put on the next plane to Munich where he was charged under the German law of “defaming the memory of the dead.” He was fined 3,000DM. Pugilist that he is, Irving appealed the conviction but it was upheld and the fine increased to 30,000DM (about $20,000), made all the worse by the fact that at a public meeting in downtown Munich Irving called the judge a “senile, alcoholic cretin.” In late 1992, while in California, he received notice from the Canadian government that he would not be allowed into that country. He went anyway to receive the George Orwell award from a conservative free speech organization, whereupon he was arrested by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Irving was led away in handcuffs and deported on the grounds that his German conviction made him a likely candidate for future hate speech violations.

(In my opinion all such attempts at censoring Irving backfire. That is, if the goal is to silence Irving and prevent him from getting additional media attention for his writings, almost everything anyone has done over the years has had the opposite effect; that is, it has generated more attention to Irving and his work. I recall in 1996 when several Jewish organizations pressured St. Martin’s Press to cancel publication of Irving’s biography of Joseph Goebbels. The ensuing media brouhaha landed Irving in Time magazine, with a full page story and a four-color photograph of Irving; I remember thinking to myself, Would David Irving have received such coverage for the book had it been published as scheduled? Hell no. 99% of books, even by reputable authors published by mainstream publishing houses, receive no such media notoriety. A recent example of the “banned in Boston” effect is when the Catholic Cardinal issued a public statement earlier this year denouncing Dan Brown’s novel The Da Vinci Code. Brown and his book got head-line coverage by all the news outlets that night, featuring images of both author and the book. That’s manna from Heaven for an author! If you really want to silence David Irving, treat him with silence.)

Though his attentions have spanned the scope of the Second World War, particularly from the German’s perspective, his interest in the Holocaust has grown ever stronger. “I think that the Holocaust is going to be revised. I have to take my hat off to my adversaries and the strategies they have employed—the marketing of the very word Holocaust: I half expect to see the little ‘TM’ after it.” For Irving, he is in an intellectual war, which he described to me in military language: “I’m presently in a fight for survival. My intention is to survive until five minutes past D-Day rather than to go down heroically five minutes before the flag is finally raised. I’m convinced this is a battle we are winning.” On his web page he claims (in the third person) that “certain of the world’s organizations have targeted him for a campaign of harassment at every level, designed to injure, smear, and if possible ruin him.” How will they accomplish this feat? “Their campaign has recruited people at every level, from jobless street-people to dentists, from immigration officials to prime ministers.” But Irving will not capitulate: “The Englishman is fighting back with every legal means.”

One defining factor in Irving’s slide into denying the central tenets of the Holocaust is that he has had to earn a living by lecturing and selling books (a difficult challenge for any author), and the more he revises the Holocaust and waves the red meat of Jewish cabals and Zionist conspiracies, the more books he sells and lecture invitations he receives from fringe groups. Irving has slipped deeper into the revisionist movement not because the historical evidence has taken him there, but because he has found an audience and a receptive market. The mainstream academy has rejected him, so he has created a niche on the margins.

The irony is that Irving appears to detest the very people who most admire him. His posture among them is stiffly arrogant, his attitude disdainfully condescending. He told journalist Ron Rosenbaum in 1998: “I find it odious to be in the same company as these people. There is no question that there are certain organizations that propagate these theories which are cracked anti-Semites.” But, he confesses, “what else can I do? If I’ve been denied a platform worldwide, where else can I make m y voice heard? As soon as I get back onto regular debating platforms I shall shake off this ill-fitting shoe which I’m standing on at present. I’m not blind. I know these people have done me a lot of damage, a lot of harm, because I get associated then with those stupid actions.”

Seven years later the shoe still fits. Even the devastating loss in his trial, in which his literary corpus was dissected by a team of professional historians hired by Lipstadt and her attorneys to discredit Irving. Chief historian among them was Richard J. Evans, who subsequently penned a book entitled Lying About Hitler, in which he documented in excruciating detail the countless mistakes Irving made in his works. In his defense Irving argued that all scholars make mistakes. But Evans retorted:

There is a difference between, as it were, negligence, which is random in its effects, i.e. if you are a sloppy or bad historian, the mistakes you make will be all over the place. They will not actually support any particular point of view … On the other hand, if all the mistakes are in the same direction in the support of a particular thesis, then I do not think that is mere negligence. I think that is a deliberate manipulation and deception.

Evans is right. And that’s a shame because it is a great waste of a great talent. How and why did this happen?

David Irving has always had a fascination with all things German. His father was a Royal Navy commander who served at the greatest naval battle of the First World War, the Battle of Jutland between English and German battleships, and on Arctic convoys during the Second World War. Irving was born in 1938 and his parents separated when he was young; his father, John Irving, was reunited with his son only in the last two years of his life, when David was in his late twenties. So there was clearly a missing father figure—no family Führer for the young David Irving.

With three siblings and a single mom, who was a commercial artist who had studied at the Slade School of Art, the strained economics took its toll on the family and Irving developed a confrontational personality. As a young pupil at Sir Anthony Browne’s grammar school in Brentwood, Essex, for example, he selected as a school prize a copy of Mein Kampf, not so much because he wanted to read the book, he admitted, but because of its shock value. Irving also recalls the “great deprivations” of the war, including going “through childhood with no toys. We had no kind of childhood at all. We were living on an is land that was crowded with other people’s armies.” He also witnessed, he says, the press’ cartoon caricatures of the Nazi leaders. “There was fat old Göring and Hitler with his postman’s hat, and there was Dr. Goebbels, who was shorter and had one leg shorter. And it seemed to me at that time, as a youngster, there was something odd in the fact that these cartoon characters were able to inflict so much indignity and deprivation on an entire country like ours.”

Although he was a good student who studied physics at Imperial College London and economics at University College London, he failed to complete either degree and dropped out of college altogether. Perhaps he was distracted by his political activism. At Imperial College, for example, he joined the Young Conservatives and edited two magazines, one founded by H. G. Wells called Phoenix and the other called Carnival Times. It was here that he caused a commotion over lost profits of the magazine that were to go to a South African organization of which Irving did not approve. At University College he spoke alongside Oswald Mosley, the founder of the British Union of Fascists, in support of the motion “This House would restrict Commonwealth immigration.”

After failing to complete his degrees, Irving moved to Germany and worked in a steel factory where he learned the German language and culture first hand. It was here that he first heard about the allied mass bombing of Dresden (from the German perspective, of course), which led to the publication of his first book The Destruction of Dresden, and his decision to become a writer. His empathy for the plight of the Germans during the war, and his sympathetic portrayal of the Nazi leaders, led him into what he calls “the Magic Circle”—the surviving former Hitler confidants. And it is here where he chose the path down which he has never diverted.

In sociology there is problem known as the “co-option” of scholars, particularly by cults and New Age religions, whereby a scholar, in entering a group and spending considerable time with them, publishes a paper or book that is not as objective as he or she perhaps believes. In fact, sociologists Stephen Kent and Theresa Krebs have identified numerous cases of “when scholars know sin” (an article in a 1998 issue of Skeptic magazine), where allegedly nonpartisan, unbiased scholars find themselves the unwitting tools of fringe groups striving for social acceptance and in need of the imprimatur of an academic. The problem is not merely one of exposure. Such groups need mainstream credibility that they can get from the academy. Academics need original research projects that they can get from studying fringe groups. The process involves a feedback loop between scholar and subject, where the more open and sympathetic the scholar appears, the more the subject opens up with honest portrayals of the group. But it is not enough for the scholar to fake a conciliatory attitude. Humans are good at detecting deception. The best way to beat a lie detector is to believe the lie yourself. That way your body will not betray you. (Evolutionary psychologists speculate that there was a deception/deception-detection arms race in human evolutionary history, where we became good at both lying and detecting lies.) Deception becomes self-deception.

In my opinion, Irving’s self-deception began when he entered the Magic Circle. “I carried out major interviews with all these people on tape. And what struck me very early on … is that you’re dealing with people who are educated people.” Hitler, he explained, “had attracted a garniture of high-level educated people around him. The secretaries were top-flight secretaries. The adjutants were people who had gone through university or through staff college and had risen through their own abilities to the upper levels of the military service.” These Hitler confidants were well-educated and they spoke highly of their Führer. Who was Irving to argue? “Coming as I did with an as-yet-unpainted canvas, this was really the seminal point, the seminal experience—to find twenty-five people of education, all of whom privately spoke well of him. Once they’d won your confidence and they knew that you weren’t going to go and report them to the state prosecutor, they trusted you. And they thought, well, now at last they were doing their chief a service.”

That was the shift from deception to self-deception, the co-option of David Irving by Hitler’s Magic Circle. Hitler’s war became Irving’s war. The Faustian bargain was made, and David Irving shall forever pay the price. Yet, with his background and temperament, it is a pact he could not help but form, and a cost he is only too willing to incur.

A Reminder of Upcoming Events…

Brain, Mind & Consciousness

The Skeptics Society Annual Conference

Friday, Saturday, Sunday, May 13–15

at the Westin Resort & Hotel

and the Beckman Auditorium, Caltech, Pasadena, CA

Letting Go of God

Julia Sweeney

Sunday, May 15th, 3:00–5:30 pm show

Hudson Backstage Theater, Hollywood, CA

followed by dinner at Julia’s home

For more information about these events and lectures,

see www.skeptic.com.