Lecture Sunday: Michael Gazzaniga

Who’s in Charge? Free Will & the Science of the Brain

Sunday, November 20, 2011 at 2 pm Baxter Lecture Hall

DO WE HAVE FREE WILL or are our lives simply determined by the same physical laws that control the world around us? For the most part, science has embraced the determinist point of view. But the U.C. Santa Barbara psychologist Michael S. Gazzaniga—the man Tom Wolfe has called “one of the most brilliant experimental neuroscientists in the world”—is not convinced. Gazzaniga argues that the human mind acts to constrain the brain and monitor our behavior, much as a government, created by a society, provides constraints on those who conceived it. Drawing on cutting-edge neuroscience and psychology, as well as ethics and law, he offers a deeply considered case for human responsibility: we are accountable for our actions.

Tickets are first come, first served at the door. Seating is limited. $8 for Skeptics Society members and the JPL/Caltech community, $10 for nonmembers. Your admission fee is a donation that pays for our lecture expenses.

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG What’s God Got To Do With It?

Michael Shermer chimes in on the House of Representatives voting last week by a margin of 396–9 to reaffirm as the national motto the phrase “In God We Trust.” God may be invoked in the national motto, but He has nothing to do with why Americans are free and secure…

About this week’s eSkeptic

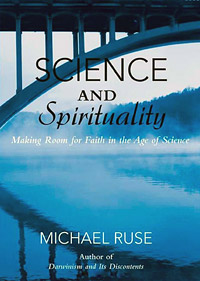

In this week’s eSkeptic, Paul J. Cech reviews Michael Ruse’s Science and Spirituality: Making Room for Faith in the Age of Science (2010, Cambridge University Press).

Making Room for Religion

by Paul J. Cech

In Science and Spirituality, Michael Ruse offers believers (especially Christians) the possibility that their beliefs can coexist with science as they contemplate ideas “that go beyond the reach of science (233).” He simultaneously offers scientists and scholars an historic and liberal view of a world where science and human values help us to increase our understanding and strengthen our respect for those who see things differently. He also offers interested general readers a readable, rational account of the history and philosophy of evolution.

The first four chapters are a detailed historical account of scientific thought in Western civilizations. Ruse provides perspectives on organic and mechanical metaphors, as he methodically explains their details in a manner that will not only refresh or enhance the understanding of scientists and other learned scholars, but in a way that provides background information for students and general readers to refer to as they delve into the analysis that is the focus of subsequent chapters. In the Introduction, Ruse provides information on the players in the discussion about religion and science. Among them are: Steven Weinberg, Sir John Polkinghorne, Francis Crick, James Watson, Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Arthur Peacocke, and Stephen Jay Gould.

Chapter One, The World as an Organism, covers the Greek perspective, and the use of metaphor in science. Chapter Two, The World as a Machine, focuses on the development of science “from Copernicus to Newton.” It concludes with more details about the machine metaphor: “The world as a machine is not something discovered…It is something we create in conjunction with nature” (52). In Chapter Three, Organisms as Machines, the focus is on philosophy. The reader is offered greater details about the machine metaphor and various philosophical perspectives on organisms, mechanisms, and evolution. This is the point where I had to get my copy of Samir Okasha’s Philosophy of Science: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2002) down from the shelf and placed nearby for comfort. The ideas of several philosophers were presented, among them Kant and Descartes. There are also ideas from scientists and thinkers such as: Heinrich Gustav Magnus, Edward Franklin, Charles Darwin, T.H. Huxley, and Richard Dawkins. With Chapter Four, Thinking Machines, I returned to a more comfortable arena. Here one finds the ideas of William James, Noam Chomsky, Edward O. Wilson, Stephen Pinker, and Paul Thagard. I was even pleasantly surprised by references to Viktor Frankl and Rollo May (104). The ideas presented in the first four chapters cover questions and ideas related to the history of scientific thought and they prepare the reader for the analysis that follows. In Chapter Five, Unasked Questions, Unsolved Problems, includes discussion of origins, morality, minds, and purpose. The ideas of various thinkers are used to explore the question, “Why is there something rather than nothing?” The ideas related to morality had me returning to the my bookshelf to get an old, well-worn copy of Jacob Bronowski’s Science and Human Values (Harper Colophon Books, 1975), in which civilization asks science and Nagasaki, which is described as an “industrial slum”, the question: Is You Is Or Is You Ain’t My Baby? It dawned on me while reading this chapter that as civilized individuals, as scientists and scholars asking questions about origins, morality, minds and purpose, is there really room for faith in this scientific age? This thought remained with me as I made my way through the remaining chapters. Chapter Six, Organicism, addresses a call for the return to the organic metaphor from the machine metaphor. Ruse presents detailed information about Naturphilosphie and other developments, as well as emergence, Gaia and ecofeminism, and he provides a summary of organicism. In the final two chapters on God and Morality, Souls, Eternity, Mystery, Ruse presents the theological foundations of faith for Christians, especially as they relate to the idea of God. Ruse aims not to prove “the truth of Christianity but to make room for it in the face of science” (193). A key point here is the rejection of theological concepts or ideas rooted in faith if they cannot hold up to the light of modern science.

In his Conclusion, Ruse states that he hopes that the “ideas and conclusions” found in Science and Spirituality will “inspire” others to join him in making room for faith in an age of science. I think it will. How? Early in the book, Ruse quotes the New York Times science writer Natalie Angier saying that science “has made it possible for people not to be religious.” I like that. Religion in general—more specifically, belief in god—comes with mixed blessings. I wholeheartedly agree that theology needs to be aligned with the findings of modern science. Theology needs to adapt. Religious beliefs need to be revised. Social Sciences have also shown us that religion has a purpose in society; it helps to reinforce norms that I hope are in step with modern science, and religion helps to alleviate anxiety, something that may be necessary for pious folk who truly believe as they face numerous concerns on a daily basis. Ruse wrote Science and Spirituality to help believers, especially Christians, to see that their beliefs can co-exist with science. But he also makes it possible for scientists and scholars to see the possibility of science that coexists with the humanities. This unification may help us all to accept and understand each other a little better. It may also help us to be better prepared if civilization has a need to ask science, is you is or is you ain’t my baby? ![]()

About the Author

Paul J. Cech is a poet and educator. His interests include evolution, human behavior (socialization and cognition), and American culture and society. He is a member of The National Center for Science Education (NCSE), The History of Science Society, Society for Police and Criminal Psychology (SPCP), APA Div. 2, and the Pennsylvania Geographical Society (PGS). His formal education includes Associate Letters, Arts, and Sciences (writing) Pennsylvania State University—Fayette 1979; BA (Psychology) California University of Pennsylvania (CUP) 1981; Pennsylvania Teaching Certificate (Secondary Social Studies) CUP 1983; MA (Geography and Regional Planning) CUP 1987. He is a member of Pi Gamma Mu and Gamma Theta Epsilon. Cech’s book reviews have been published in The Pennsylvania Geographer, ISIS, and The Quarterly Review of Biology. His latest poems were published on The Other Voices International Project, Vol. 45.

Suggested reading on religion, science and spirituality…

-

The Soul of Science by Michael Shermer

The Soul of Science by Michael Shermer

-

Reinventing the Sacred: A New View of Science, Reason & Religion by Dr. Stuart Kauffman

Reinventing the Sacred: A New View of Science, Reason & Religion by Dr. Stuart Kauffman

-

Rational Mysticism: The Border Between Science & Religion by John Horgan

Rational Mysticism: The Border Between Science & Religion by John Horgan