DATE CORRECTION NOTICE: Dr. Peter Diamandis’ lecture will take place on Sunday, February 26, 2012 at 2 pm. It was incorrectly stated as Saturday in last week’s eSkeptic.

In this week’s eSkeptic:

- Follow Michael Shermer: Alfred Russel Wallace and The Nature of Science

- Skepticality: Interview with Daniele Bolelli

- New Episode: Mr. Deity and The Occupation

- Feature Article: Darwin’s Legacy

- Upcoming Lecture at Caltech: Dr. Peter Diamandis

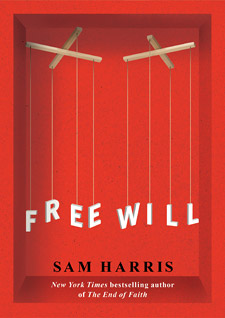

- Special Double Caltech Event: A debate, and a lecture (Sam Harris)

- Fundraising Drive on Now: Help Send Skepticism 101 into the World!

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

The Natural & the Supernatural:

Alfred Russel Wallace and The Nature of Science

A couple weeks ago, Michael Shermer participated in an online debate at Evolution News & Views with Center for Science & Culture fellow Michael Flannery on the question: “If he were alive today, would evolutionary theory’s co-discoverer, Alfred Russel Wallace, be an intelligent design advocate?” In this week’s Skepticblog, we present part three of the debate.

Interviews with Tom Merritt, Bob Blaskiewicz & Eve Siebert

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 176

This week on Skepticality, Derek sits down with Tom Merritt to discuss the importance of critical thinking when assessing heated issues such as the much-reported working conditions at computer manufacturer Foxconn, a large supplier of Apple components. Then, Bob Blaskiewicz and Eve Siebert join Derek to discuss the evidence that Shakespeare was actually the man who penned the famous plays of the Globe Theater, and how the movie Anonymous is steeped in fiction.

The Latest Episode of Mr. Deity: Mr. Deity and the Occupation

WATCH THIS EPISODE | DONATE | NEWSLETTER | FACEBOOK | MrDeity.com

About this week’s eSkeptic

In this week’s eSkeptic, Donald R. Prothero remembers Charles Darwin (on the occasion of what would have been his 203rd birthday this past Sunday). Prothero reminds us that it was 40 years ago this year that the most frequently cited paper in the history of paleontology was published: none other than the legendary 1972 article by Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould which proposed the “punctuated equilibrium” hypothesis. Prothero also shares some insights from his own research.

Read Prothero’s bio after the article.

Darwin’s Legacy

by Donald R. Prothero

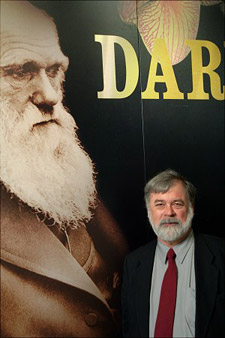

Niles Eldredge as he looks today, Curator Emeritus at the American Museum of Natural History

Last Sunday, February 12, we celebrated the 203rd birthday of two of the most important figures in world history, Abraham Lincoln—and Charles Darwin. To mark the occasion properly, I spent part of my weekend visiting the Creation Museum in Santee, California, with Carrie Poppy and Ross Blocher of the podcast “Oh no, Ross and Carrie!” (more on that trip in my March 7 Skepticblog post). But I thought I’d mark this anniversary with a discussion of another important anniversary in the history of evolutionary science.

It was 40 years ago this year that the most frequently cited paper in the history of paleontology was published. That was none other than the legendary 1972 article by Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould which proposed the “punctuated equilibrium” hypothesis. (Full disclosure: I took seminars from Niles while I was a student at the American Museum of Natural History, and Steve Gould was very interested in and supportive of my research even though I was not his student in a formal sense). At the time the paper came out, the dominant concept about speciation was the allopatric speciation model. In a nutshell, good biological evidence showed that new species arise not in the large mainland populations (with their extensive gene mixing) but in small isolated populations with unusual gene frequencies (peripheral isolates), usually living separate (allopatric) from the mainland population. Once these allopatric populations were no longer isolated but remixed with the mainland population, they would be genetically and behaviorally distinct from their parent species. Thus, they would be no longer capable of interbreeding, which is part of the definition of a biological species.

Experimental biology … may reveal what happens to a hundred rats in the course of ten years under fixed and simple conditions, but not what happened to a billion rats in the course of ten million years under the fluctuating conditions of earth history. Obviously the latter problem is more important.

Even though the allopatric speciation model was accepted by biologists as early as 1942, it took paleontologists 30 years to recognize its implications. In their historic 1972 paper, Niles and Steve pointed out that if you took Ernst Mayr’s allopatric speciation model seriously, it would predict that species should arise in a normal biological time frame: a few years to a few hundred years at most. That’s a geologic instant, the difference between one bedding plane and the next in strata that span millions of years. The allopatric speciation model also predicted that species should arise in small, peripherally isolated areas, so they were unlikely to be fossilized in the few places for which we have a good fossil record. Rather than slow gradual change through millions of years of strata (the “phyletic gradualism” model), the allopatric speciation model accepted by biologists should give a fossil record where species seem to appear suddenly without any gradual transition preserved (“punctuation”), and then persist for long periods of time without change (“equilibrium”).

(left–right) Stephen Jay Gould, Michael Shermer, and yours truly, Mt. Wilson Observatory, Pasadena,CA (2001)

The “punctuated equilibrium” paper is a masterpiece of writing and incisive thinking, which poses a number of interesting issues. The first part is a general discourse on the philosophy of science, which argues that all scientists are products of their time and culture and tend to see what they expect to see. In this context, Darwin led paleontologists to expect phyletic gradualism, which they vainly tried to document for over a century before the allopatric speciation model came along. Then Eldredge and Gould introduced the details of the allopatric model, described punctuated equilibrium, and give examples from their own research (phacopid trilobites from Eldredge, Bahamian land snails from Gould). Every time I teach a paleontology class, I always assign the original paper as required reading, and then lead a class discussion section teasing it apart. Like fine wine, the paper gets better every time I reread it. I’m always amazed at what insights it contains, what future debates it triggered or foreshadowed, and how different students pick up different elements when they read it for the first time.

For the first decade after the paper was published, it was the most controversial and hotly argued idea in all of paleontology. Soon the great debate among paleontologists boiled down to just a few central points, which Gould and Eldredge (1977) nicely summarized on the fifth anniversary of the paper’s release. The first major discovery was that stasis was much more prevalent in the fossil record than had been previously supposed. Many paleontologists came forward and pointed out that the geological literature was one vast monument to stasis, with relatively few cases where anyone had observed gradual evolution. If species didn’t appear suddenly in the fossil record and remain relatively unchanged, then biostratigraphy would never work—and yet almost two centuries of successful biostratigraphic correlations was evidence of just this kind of pattern. As Gould put it, it was the “dirty little secret” hidden in the paleontological closet. Most paleontologists were trained to focus on gradual evolution as the only pattern of interest, and ignored stasis as “not evolutionary change” and therefore uninteresting, to be overlooked or minimized. Once Eldredge and Gould had pointed out that stasis was equally important (“stasis is data” in Gould’s words), paleontologists all over the world saw that stasis was the general pattern, and that gradualism was rare—and that is still the consensus 40 years later.

The debate was less than a decade old when I was wrapping up my dissertation work in 1981. In my dissertation on the incredibly abundant and well preserved fossil mammals of the Big Badlands of the High Plains, I had over 160 well-dated, well-sampled lineages of mammals, so I could evaluate the relative frequency of gradualism versus stasis in an entire regional fauna. I also had a wide geographic spread (from Montana and Saskatchewan to Texas, but mostly in the Dakotas, Nebraska, Wyoming, and Colorado). I had large fossil samples of many species, with dozens at each level, and excellent stratigraphic data. When I finally plunged in and plotted and analyzed my data carefully, it was clear that nearly every lineage showed stasis, with one minor example of gradual size reduction in the little oreodont Miniochoerus. I could point to this data set and make the case for the prevalence of stasis without any criticism of bias in my sampling. More importantly, the fossil mammals showed no sign of responding to the biggest climate change of the past 50 million years (the Eocene-Oligocene transition, when glaciers appeared in Antarctica after 200 million years). In North America, dense forests gave way to open scrublands, crocodiles and pond turtles were replaced by land tortoises, and the snails changed from those typical of Nicaragua to those of Baja California. Yet out of all the 160 lineages of mammals in this time interval, there was virtually no response. To paraphrase Rhett Butler, “Frankly, my dear, the mammals don’t give a damn.”

This result intrigued me, so I began to re-examine the uncritical acceptance of the notion that fossil mammals track environmental changes. It occurred to me that our excellent database of North American fossil mammals and global climate change might be a good place to test this hypothesis. In a 1999 paper, I argued that for the four biggest independently documented periods of climatic change in the past 50 million years, the mammals either do not respond at all, or show much less speciation and extinction than they do at times when there is no evidence of climatic change. One interval included the middle-late Eocene climate change at 37 million years ago, when turnover was merely at background level, despite evidence of floral change elsewhere in North America, and a big climatic cooling event in the global oceans. The second was the Eocene-Oligocene transition just discussed. The third was the great expansion of modern grasslands at 7.5 million years ago, long after mammals with high-crowned grazing teeth appeared at 15 million years ago. In fact, there is almost no significant faunal change at 7.5 million years ago. The final example is the last 2 million years of ice ages, when climate changed dramatically, but speciation did not occur in response to climate. Instead, most ice age mammals simply migrated north and south in response to the movements of the ice sheets.

About six years ago, I decided to test this last idea. Back in 2006, I had a bunch of excellent students in my paleontology classes at both Occidental and Caltech, and several wanted to do research with me. I was at a loss over how to supervise so many undergraduates with limited backgrounds, until I realized that we could do a group of related projects practically in our back yard: the Page Museum at La Brea tar pits in Los Angeles. I equipped each one of them with calipers and gave them a measuring protocol, and got them access to the La Brea fossils through the collections managers. Then they each measured a different Ice Age mammal or bird, collecting data on hundreds of bones from all the tar pits with good radiocarbon dates: saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, giant lions, bison, horses, camels, ground sloths, plus the five most common birds: golden and bald eagles, condors, caracaras, and turkeys. After six years of work and publication, the conclusion is clear: none of the common Ice Age mammals and birds responded to any of the climate changes at La Brea in the last 35,000 years, even though the region went from dry chaparral to snowy piñon-juniper forests during the peak glacial 20,000 years ago, and then back to the modern chaparral again.

In four of the biggest climatic-vegetational events of the last 50 million years, the mammals and birds show no noticeable change in response to changing climates. No matter how many presentations I give where I show these data, no one (including myself) has a good explanation yet for such widespread stasis despite the obvious selective pressures of changing climate. Rather than answers, we have more questions—and that’s a good thing! Science advances when we discover what we don’t know, or we discover that simple answers we’d been following for years no longer work.

Clearly, it is an interesting time to be a paleontologist. As Gould (1983) put it, from the “irrelevance” of the early 1900s to the “subservient” role that George Gaylord Simpson placed us in 1944, paleontology is now in the driver’s seat, and trying to reach the “High Table” where the “High Priests” of evolution and genetics have long ruled unchallenged. Who knows where this will all end? Whatever the result, we’re clearly making advances by challenging the accepted dogmas of the time and finding their faults, and hopefully discovering something new and interesting. As Gould and Eldredge (1977) put it, “Why be a paleontologist if we are condemned only to verify what students of living organisms can propose directly?”

References

- Eldredge, N. 1985. Time Frames: The Rethinking of Darwinian Evolution and the Theory of Punctuated Equilibria. Simon & Schuster, New York.

- Eldredge, N. 1995. Reinventing Darwin: The Great Debate at the High Table of Evolutionary Theory. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- Eldredge, N., and S. J. Gould, 1972. Punctuated equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism, pp. 82-115, in Schoft, T.J.M., Models in Paleobiology. Freeman Cooper, San Francisco.

- Gould, S.J. 1980. Is a new and more general theory of evolution emerging? Paleobiology6: 119–130.

- Gould, S.J. 1982. Darwinism and the expansion of evolutionary theory. Science 216:380–387.

- Gould, S.J. 1983. Irrelevance, submission, and partnership: the changing roles of paleontology in Darwin’s three centennials, and a modest proposal for macroevolution, pp. 347-366, in Bendall, D.S. (ed.), Evolution from Molecules to Men. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Gould, S.J. 2002. The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

- Gould, S.J., and Eldredge, N. 1977. Punctuated equilibria: the tempo and mode of evolution reconsidered. Paleobiology 3:115–151.

- Prothero, D.R., 1992. Punctuated equilibrium at twenty: a paleontological perspective. Skeptic 1(3): 38–47.

- Prothero, D.R. 1999. Does climatic change drive mammalian evolution? GSA Today 9(9):1–5.

- Prothero, D.R., Syverson, V., Raymond, K.R., Madan, M., Molina, S., Fragomeni, A., DeSantis, S., Sutyagina, A., and Gage, G.L. (in press) Size and Shape Stasis in Late Pleistocene Mammals and Birds from Rancho La Brea during the last Glacial-Interglacial Cycle. Quaternary Science Reviews(in press)

- Prothero, D.R., and T.H. Heaton, 1996, Faunal stability during the early Oligocene climatic crash. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 127:239–256.

About the Author

DR. DONALD R. PROTHERO was Professor of Geology at Occidental College in Los Angeles, and Lecturer in Geobiology at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. He earned M.A., M.Phil., and Ph.D. degrees in geological sciences from Columbia University in 1982, and a B.A. in geology and biology (highest honors, Phi Beta Kappa) from the University of California, Riverside. He is currently the author, co-author, editor, or co-editor of 32 books and over 250 scientific papers, including five leading geology textbooks and five trade books as well as edited symposium volumes and other technical works. He is on the editorial board of Skeptic magazine, and in the past has served as an associate or technical editor for Geology, Paleobiology and Journal of Paleontology. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America, the Paleontological Society, and the Linnaean Society of London, and has also received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Science Foundation. He has served as the President and Vice President of the Pacific Section of SEPM (Society of Sedimentary Geology), and five years as the Program Chair for the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. In 1991, he received the Schuchert Award of the Paleontological Society for the outstanding paleontologist under the age of 40. He has also been featured on several television documentaries, including episodes of Paleoworld (BBC), Prehistoric Monsters Revealed (History Channel), Entelodon and Hyaenodon (National Geographic Channel) and Walking with Prehistoric Beasts (BBC). His website is: www.donaldprothero.com. Check out Donald Prothero’s page at Shop Skeptic.

Our Next Lecture at Caltech:

Dr. Peter Diamandis

Abundance: Why the Future Will Be Much Better Than You Think

with Dr. Peter Diamandis

Baxter Lecture Hall

DATE CORRECTION NOTICE:

This lecture will take place on

Sunday, February 26, 2012 at 2 pm.

It was incorrectly stated as Saturday

in last week’s eSkeptic.

SINCE THE DAWN OF HUMANITY, a privileged few have lived in stark contrast to the hardscrabble majority. Conventional wisdom says this gap cannot be closed. But it is closing—fast. According to the X-Prize creator and entrepreneur Peter H. Diamandis, we will soon be able to meet and exceed the basic needs of every man, woman and child on the planet. Abundance for all is within our grasp through four forces: exponential technologies, the DIY innovator, the Technophilanthropist, and the Rising Billion. Diamandis establishes hard targets for change and lays out a strategic roadmap for governments, industry and entrepreneurs, giving us plenty of reason for optimism.

Tickets are first come, first served at the door. Seating is limited. $8 for Skeptics Society members and the JPL/Caltech community, $10 for nonmembers. Your admission fee is a donation that pays for our lecture expenses.

Followed by…

- The Creative Destruction of Medicine: How the

Digital Revolution Will Create Better Health Care

with Dr. Eric Topol

Sunday, March 11, 2012 at 2 pm

SPECIAL DOUBLE EVENT

Beckman Auditorium, Caltech

Sunday March 25 starting at 2pm

Official Debate Co-Sponsor

The Great Debate:

“Has Science Refuted Religion?”

Sean Carroll & Michael Shermer versus

Dinesh D’Souza & Ian Hutchinson

Debate starts at 2pm

Download Map

Followed by Sam Harris lecturing on Free Will

Lecture starts after the debate

At no extra charge, immediately following the debate is a lecture and book signing on Free Will by Sam Harris.

This Debate/Harris lecture

is now SOLD OUT.

Tickets

The price of admission covers both events: $10 Skeptics Society members/Caltech/JPL community; $15 everyone else. Tickets may be purchased in advance through the Caltech ticket office at 626-395-4652 or at the door. Ordering tickets ahead of time is strongly recommended as this event will sell out. The Caltech ticket office asks that you do not leave a message. Instead call between 12:00 and 5:00 Monday–Friday.

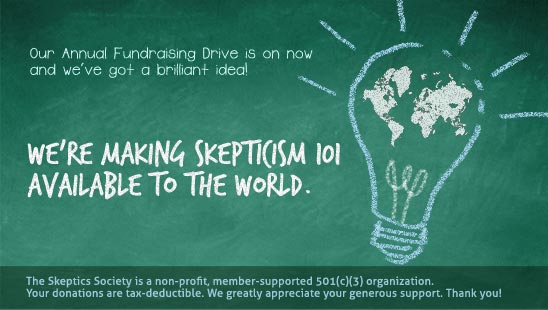

OUR ANNUAL FUNDRAISING DRIVE IS ON NOW

Help Send Skepticism 101 into the World!

- Click here to read our new plan to take Skepticism to the next level!

- Click here to make a donation now via our online store.

Monthly Recurring Donation Options Now Available

We encourage you to choose the monthly recurring donation option. Simply tell us how long you want your donation to recur (using the drop-down menu on the donation page) and we’ll set up automatic withdrawal for the amount you select.

Just for considering a donation, check out our free PDF download

created by Junior Skeptic Editor Daniel Loxton.