the Esalen Institute, Big Sur, California (photo by Angela Smith)

Esalen Institute

weekend workshop

Science, Spirituality & the Search for Meaning

a weekend seminar led by Michael Shermer

August 11th–13th, 2006

at the Esalen Institute, Big Sur, CA

The quest to understand the universe and our place in it is at the core of both religion and science. At the beginning of the 20th century social scientists predicted that belief in God would decrease by the end of the century because of the secularization of society. In fact, never in history have so many, and such a high percentage of the population, believed in God and expressed spirituality. To find out why, Dr. Michael Shermer has undertaken a monumental study of science, spirituality, and the search for meaning.

Since humans are storytelling animals, this study involves the origins and purposes of myth and religion in human history and culture. Why is there is an eternal return of certain mythic themes in religion — messiah myths, creation myths, redemption myths, end-of-the-world myths? What do these recurring themes tell us about the workings of the human mind and culture?

We are also pattern-seeking animals. For countless millennia we have constructed stories about how our cosmos was designed specifically for us. For the past few centuries, however, science has presented us with an alternative in which we are but one among tens of millions of species, housed on but one planet among many orbiting an ordinary solar system, itself one among possibly billions of solar systems in an ordinary galaxy, located in a cluster of galaxies not so different than billions of other galaxy clusters, and so on, ad infinitum. Is it really possible that this entire cosmological multiverse exists for one tiny subgroup of a single species on one planet in a lone galaxy? This workshop explores the deepest question of all: what if the universe were not created for us by an intelligent designer, and instead just happened? Can we discover meaning in this apparently meaningless universe? The answer is yes!

about the Esalen Institute

Esalen is, geographically speaking, a literal cliff, hanging precariously over the Pacific Ocean. The Esselen Indians used the hot mineral springs here as healing baths for centuries before European settlers arrived. Today the place is adorned with a host of lush organic gardens, mountain streams, a cliff-side swimming pool, hot springs embedded in a multimillion-dollar stone, cement, and steel spa, and meditation huts tucked away in the trees. Esalen was founded in 1962 by Stanford graduates Michael Murphy and Richard Price and has featured such notable visitors as Richard Feynman, Abraham Maslow, Timothy Leary, Paul Tillich, Carlos Castaneda, and B. F. Skinner. Regardless of your source of spirituality (science, religion, or self), Esalen embodies the integration of body, mind, and spirit.

about the seminar leader

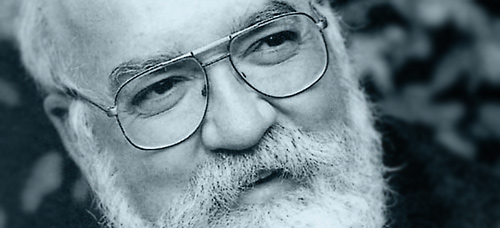

Dr. Michael Shermer is the Founding Publisher of Skeptic magazine, the Director of the Skeptics Society, a monthly columnist for Scientific American, the host of the Skeptics Lecture Series at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), and the co-host and producer of the 13-hour Fox Family television series, Exploring the Unknown.

He is the author of Science Friction: Where the Known Meets the Unknown, about how the mind works and how thinking goes wrong. His book The Science of Good and Evil: Why People Cheat, Gossip, Share Care, and Follow the Golden Rule, is on the evolutionary origins of morality and how to be good without God. He wrote a biography, In Darwin‚s Shadow, about the life and science of the co-discoverer of natural selection, Alfred Russel Wallace. He also wrote The Borderlands of Science, about the fuzzy land between science and pseudoscience, and Denying History, on Holocaust denial and other forms of pseudohistory. His book How We Believe: Science, Skepticism, and the Search for God, presents his theory on the origins of religion and why people believe in God. He is also the author of Why People Believe Weird Things on pseudoscience, superstitions, and other confusions of our time.

According to the late Stephen Jay Gould (from his Foreword to Why People Believe Weird Things):

Michael Shermer, as head of one of America‚s leading skeptic organizations, and as a powerful activist and essayist in the service of this operational form of reason, is an important figure in American public life.

Dr. Shermer received his B.A. in psychology from Pepperdine University, M.A. in experimental psychology from California State University, Fullerton, and his Ph.D. in the history of science from Claremont Graduate University. Since his creation of the Skeptics Society, Skeptic magazine, and the Skeptics Distinguished Lecture Series at Caltech, he has appeared on such shows as 20/20, Dateline, Charlie Rose, Larry King Live, Tom Snyder, Donahue, Oprah, Leeza, Unsolved Mysteries, and other shows as a skeptic of weird and extraordinary claims, as well as interviews in countless documentaries aired on PBS, A&E, Discovery, The History Channel, The Science Channel, and The Learning Channel.

registration

$655, which includes the weekend workshop, standard accommodation and meals at one of the most beautiful locations in the world (see reservations for further details and ticket options). Register for the seminar online through the Esalen Institute, (not through the Skeptics Society), or by calling (831) 667-3005.

In this week’s eSkeptic James N. Gardner reviews Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon. (Viking, 2006, ISBN 067003472X) by Daniel Dennett. James Gardner is the author of Biocosm: The New Scientific Theory of Evolution: Intelligent Life Is the Architect of the Universe (2003) and The Intelligent Universe: AI, ET, and the Emerging Mind of the Cosmos (forthcoming in 2007). Biocosm was selected as one of the ten best science books published in 2003 by the editors of Amazon.com.

Broken Spells & Unveiled Secrets

a book review by James N. Gardner

Should the tools of science be used to study the phenomenon of religion? Or should the domain of the sacred remain a shrouded enclave, shielded from the prying eyes and profane proddings of anthropologists, sociologists, economists, and evolutionary biologists?

That is the question at the heart of the philosopher Daniel Dennett’s important and timely new book Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon. Dennett, a self-described “bright” — the stylish neologism signifying a person of the atheist persuasion that he and Richard Dawkins began to promote in twin op-ed essays in 2003 — comes out squarely in favor of scientific scrutiny of the origin and nature of religious faith:

It is high time that we subject religion as a global phenomenon to the most intensive multidisciplinary research we can muster, calling on the best minds on the planet. Why? Because religion is too important for us to remain ignorant about. It affects not just our social, political, and economic conflicts, but the very meanings we find in our lives. For many people, probably a majority of the people on Earth, nothing matters more than religion. For this very reason, it is imperative that we learn as much as we can about it. That, in a nutshell, is the argument of this book.

Religion has, of course, been studied previously, both from the inside by theological scholars as diverse in viewpoint as Augustine, Emil Durkheim, and Mircea Eliade, and from the outside by pioneering investigators like William James and continuing throughout the 20th century by anthropologists, sociologists, and psychologists. But only recently have the sophisticated techniques of modern science — statistical analysis, investigatory methodologies developed in the fields of sociobiology and evolutionary psychology, and methods used to associate genetic patterns with particular categories of behavior — been deployed in order to put religion under the microscope of objective, unbiased scientific analysis. Only now, in fact, do we possess the tool kit — especially the computational techniques — to allow scientists to develop sophisticated models of the evolution of religious culture, analogous to dynamic software models of linguistic evolution and viral mutation.

The approach advocated by Dennett — forthright demystification of a domain of human experience whose very essence is mystery, irrationality, and faith — has provoked predictable opposition, some of it from surprising quarters. In a review of Breaking the Spell published in The New York Review of Books Princeton physicist Freeman Dyson, forthrightly conceding his own pro-religion bias, chided Dennett for wearing his atheistic prejudices on his sleeve:

My own prejudice, looking at religion from the inside, leads me to conclude that the good vastly outweighs the evil … Without religion, the life of the country would be greatly impoverished … Dennett, looking at religion from the outside, comes to the opposite conclusion. He sees the extreme religious sects that are breeding grounds for gangs of young terrorists and murderers, with the mass of ordinary believers giving them moral support by failing to turn them in to the police. He sees religion as an attractive nuisance in the legal sense, meaning a structure that attracts children and young people and exposes them to dangerous ideas and criminal temptations, like an unfenced swimming pool or an unlocked gun room.

But the whole point of Dennett’s thoughtful book — regrettably obscured by anti-religious rhetoric that would get him stricken from any jury empanelled to adjudicate the merits of his argument — is precisely that the origins, developmental pathways, and internal dynamics of religious communities and belief systems should be subjected to intense scientific investigation, not shunned mindlessly as pathologies associated with the consumption of dangerous and outmoded cultural opiates. To argue otherwise — to either dismiss the societal value proposition of religion ab initio or to agree with the late Stephen Jay Gould that religion and science are separate “magisteria” that should be contemplated in utter isolation and remain forever separated by a rigid cordon sanitaire — is not only literally irrational but also profoundly at odds with basic lessons of history. As I pointed out in my book Biocosm:

The overlapping domains of science, religion, and philosophy should be regarded as virtual rain forests of cross-pollinating ideas — precious reserves of endlessly fecund memes that are the raw ingredients of consciousness itself in all its diverse manifestations. The messy science/religion/philosophy interface should be treasured as an incredibly fruitful cornucopia of creative ideas — a constantly coevolving cultural triple helix of interacting ideas and beliefs that is, by far, the most precious of all the manifold treasures yielded by our history of cultural evolution on Earth.

In his classic Lowell Lectures delivered at Harvard in 1925, British philosopher Alfred North Whitehead put forward an intriguing explanation for the curious fact that European civilization alone had yielded the cultural phenomenon we know as scientific inquiry. Whitehead’s theory was that “the faith in the possibility of science, generated antecedently to the development of modern scientific theory, is an unconscious derivative from medieval theology.” More specifically, he contended that

the greatest contribution of medievalism to the formation of the scientific movement [was] the inexpugnable belief that every detailed occurrence can be correlated with its antecedents in a perfectly definite manner, exemplifying general principles. Without this belief the incredible labours of scientists would be without hope. It is this instinctive conviction, vividly poised before the imagination, which is the motive power of research — that there is a secret, a secret which can be unveiled.

Whence this instinctive conviction that there is discoverable pattern of order in the realm of nature? The source of the conviction, in Whitehead’s view, was not the inherently obvious rationality of nature but rather a peculiarly European habit of thought — a deeply ingrained, religiously derived, and essentially irrational faith in the existence of a rational natural order. The scientific sensibility, in short, was an unconscious derivative of medieval religious belief in the existence of a well-ordered universe that abides by invariant natural laws that can be discovered by dint of human investigation.

If Whitehead is correct, religion is not at all alien to scientific thought but bears an ancestral relationship to the set of intellectual disciplines that define our concept of modernity. Western religion, in short, is the father of Western science. What could be more fitting, then, than for science to focus the lens of skeptical inquiry on issues relating to its own dimly understood paternity — that is to say, on religious belief, the historical source of scientists’ boundless faith in the discoverable rationality of the cosmos.

also of interest…

For further reading, you may wish to check out Michael Shermer’s review of Breaking the Spell, which appeared in eSkeptic for February 23rd, 2006. Also, available at Shop Skeptic, is Daniel Dennett’s lecture at Caltech, based on the book.