FREE AUDIO DOWNLOAD

a Chapter from Mind of the Market

In his book The Mind of the Market, Dr. Michael Shermer attempts to answer the question of how we evolved from simple hunter-gatherers such as the Yanamamo people of Brazil to complex consumer-traders such as the Manhattanite people of New York. The Yanamamo have about 300 products, compared to the 10 billion products of the Manhattanites. How did this happen, and why? In this free audio download of the first chapter, Dr. Shermer outlines the problem to be solved and the sciences used to solve it, starting with the study of complex adaptive systems. Evolution and economics are equally counterintuitive for most people to grasp because they look like they were designed from the top down when, in fact, they evolve from the bottom up: in evolution animals are just running around trying to make a living and get their genes into the next generation; in economics people are just running around trying to make a living and get their genes into the next generation. Out of all this running around people develop trust between strangers and begin to trade with them to establish and maintain trusting relationships between groups, and this is what started us down the long path toward modernity.

DOWNLOAD the sample MP3 (22MB)

In this week’s eSkeptic, James N. Gardner reviews Remarkable Creatures: Epic Adventures in the Search for the Origins of Species by Sean B. Carroll. James N. Gardner is an Oregon attorney and the author, most recently, of The Intelligent Universe: AI, ET, and the Emerging Mind of the Cosmos.

Remarkable Creatures

Epic Creatures, Remarkable Species

a book review by James N. Gardner

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the publication of Charles Darwin’s masterpiece On the Origin of Species. While this event, so seminal in the history of science, will be celebrated in a number of books slated to appear in 2009, none is likely to prove more compelling a read than Sean Carroll’s Remarkable Creatures.

The “remarkable creatures” of which Carroll writes are both the amazing denizens of the biosphere whose existence and ecological niches were largely unknown before 1859, and the brave scientific adventurers who journeyed far and wide to study life on Earth. As Carroll puts it:

They are, without exception, remarkable people who have experienced and accomplished extraordinary things. They have lived the kinds of lives that [Mark] Twain extolled — they walked where no others had walked, saw what no one else had seen, and thought what no one else had thought.

Remarkable Creatures encompasses a vast span of geography and history, beginning with Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt’s five-year expedition through Central and South America at the beginning of the 19th Century and ending with the dawn of the new science of astrobiology, which searches for and imagines the nature of extraterrestrial life forms yet to be discovered.

Three of the best chapters in the book chronicle the intermingled lives of Charles Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace, and Henry Walter Bates. Darwin is, of course, the most famous of the trio but what is often overlooked is how vital were the contributions of Wallace and Bates to the birth and acceptance of Darwin’s theory of speciation through natural selection. Darwin sketched out his theory almost two decades before On the Origin of Species appeared but kept silent about his revolutionary ideas because of fear of ostracism. As Carroll writes: “His species theory was heresy to the dogma of special [divine] creation, and he knew that heretics were not treated well. It was too much of a risk to gamble his soaring reputation on his species theory.”

What finally broke Darwin’s silence was fear of a different kind — terror that his theory would be eclipsed by the work of a young naturalist named Alfred Russel Wallace who had independently developed a theory of natural selection nearly identical to Darwin’s. When Darwin famously received Wallace’s short paper sketching out the latter’s evolutionary ideas in June of 1858, Darwin went into panic mode, confessing that he “feared that all of my originality, whatever it may amount to, will be smashed.” In the end, Wallace’s paper and a brief outline of Darwin’s theory were read together at a meeting of a leading scientific society. Darwin’s great book was subsequently published and the rest is history.

Would Darwin’s name be known to us and forever associated with the theory of evolution absent the goad of fear furnished by Wallace’s meager little paper? We shall never know. Nor shall we ever know whether Darwin’s theory would have prevailed absent the early validation provided by the third member of the trio — naturalist Henry Walter Bates. Bates spent eleven incredible years exploring the wonders of the massive Amazon river system. The privations he suffered during those years — unrelenting heat, yellow fever, fire ants, biting flies and intense loneliness — were offset by extraordinary rewards. As Carroll writes:

Those rewards were many — river dolphins, anteaters, frigate birds, anacondas, hummingbirds, bird-eating spiders, all sorts of monkeys, jaguars, caimans, blue hyacinthine macaws, parrots, eagles, fives species of toucans, and butterflies — flocks of butterflies. Bates collected 14,712 animal species in all, of which more than 8,000 were new to science.

Of special importance to Darwin’s new theory were Bates’ discoveries concerning butterflies. After returning to England, Bates wrote his most important scientific paper, which described the phenomenon of mimicry among butterfly species and explained it by means of Darwinian natural selection. Butterfly species edible by predators, Bates noted, could grow to resemble unpalatable butterfly species as a survival strategy. The phenomenon of mimicry became an important source of support for the theory of evolution.

Shortly after Wallace returned to England from his journey abroad, he and Bates spent a memorable weekend with Darwin celebrating their mutual adventures in scientific discovery. One can imagine Bates telling his two colleagues something he later wrote about his own deep linkage with Darwin’s theory, “I think I have got a glimpse into the laboratory where Nature manufactures her new species.”

Wild at Heart?

Do animals mourn the loss of their mates? When a human child fell into the gorilla enclosure at the Brookfield zoo in 1996, why did a mother gorilla named Binti protect and cradle the child and help return him to the zoo staff? This week on Skepticality, Swoopy talks with Dr. Marc Bekoff, Professor Emeritus of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Colorado and author of Wild Justice. His book examines the differences and startling similarities between the observed morality and emotions of human and non-human animals.

Marrying years of behavioral and cognitive research with compelling and moving anecdotes, Dr. Bekoff and his co-author Jessica Pierce reveal that animals exhibit a broad repertoire of moral behaviors, including fairness, empathy, trust, and reciprocity. Underlying these behaviors is a complex and nuanced range of emotions, backed by a high degree of intelligence and surprising behavioral flexibility.

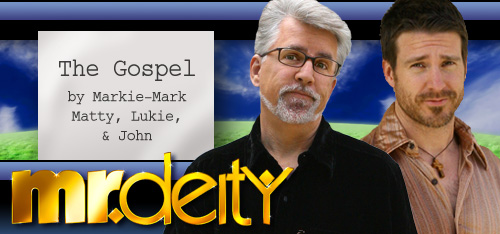

Mr. Deity and the Scripts

Mr. Deity finds Jesse/Jesus confounded by the acting challenge of four different scripts (the Gospels) which, to him, seem “all over the place” and completely contradictory. The two attempt to whittle things down to one, coherent narrative.

WATCH this episode

The latest additions to MichaelShermer.com and SkepticBlog.org

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

Mixing Science and Politics (and Economics)

Although the Skeptics Society is apolitical, Michael Shermer sometimes explores political and economic issues in his personal blog. In this week’s Skepticblog post, Michael responds to some of his critics. • READ the blog post •