In this week’s eSkeptic:

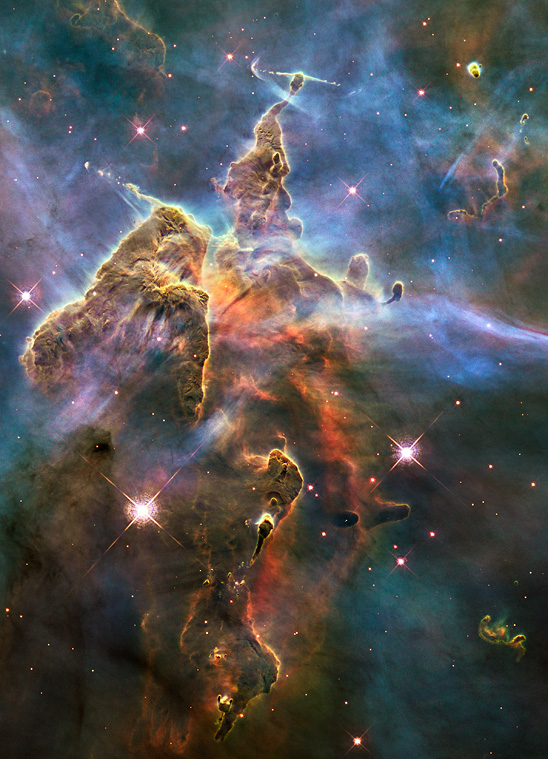

About the image above

Hubble’s 20th anniversary image shows a mountain of dust and gas rising in the Carina Nebula. The top of a three-light-year tall pillar of cool hydrogen is being worn away by the radiation of nearby stars, while stars within the pillar unleash jets of gas that stream from the peaks. Credit: NASA, ESA, and M. Livio and the Hubble 20th Anniversary Team (STScI)

About this week’s feature article and its author

In this week’s eSkeptic, Justin Trottier reviews Ray Jayawardhana’s new book Strange New Worlds: The Search for Alien Planets and Life Beyond Our Solar System.

Justin Trottier is the National Executive Director of the Centre for Inquiry Canada, and the chief spokesperson for the Canadian Atheist Bus Campaign and the Extraordinary Claims Campaign. He is a regular contributor to the Michael Coren Show on CTS TV, the John Oakley Show on AM640 and the National Post’s religion blog. He has spoken on diverse topics including ethics, the paranormal and secularism on a variety of programs on every major Canadian network, including CBC’s The National, CTV’s Canada AM and TVO’s The Agenda.

SUBSCRIBE to Skeptic magazine for more great articles like this one.

Stranger Than We Can Imagine

by Justin Trottier

To invoke a quote often attributed to the astronomer Arthur Stanley Eddington, “Not only is the universe stranger than we imagine, it is stranger than we can imagine.” Many areas of scientific exploration have led to surprising discoveries never envisioned, and the hunt for new exoplanets—worlds beyond our solar system—is a splendid example.

In Strange New Worlds, the University of Toronto astronomer Ray Jayawardhana offers a glimpse into the real and often messy way science is done, along with the exhilarating surprises thrown at pioneering scientists. No one thought the first exoplanet would be discovered around the unlikely location of a pulsar, or that gas giants would be found so far from where they are in our own solar system. Some exoplanets are so close to their parent star that they orbit in a matter of days, whereas one exoplanet that is eight Jupiters in mass, was found more than 10 times the distance of Neptune to our sun.

Jayawardhana’s own studies of infant planetary systems offers one clear surprise. Early solar systems are far more complicated, chaotic and dangerous than we thought. This discovery may have tremendous impact on our understanding of our own birthing process. Consider for example the finding that gas giant planets often migrate. Now researchers think our solar system’s own so-called “late heavy bombardment” period that occurred 600 million years after initial planetary formation, as evidenced by lunar craters, may be explained by the migration of our own planets.

While cosmology explores the earliest moments of the cosmos and abiogenesis seeks to understand the origin of life, Jayawardhana and his planet hunters are filling in a crucial middle of the story origin account. It is a narrative description of how those materials generated by the universe can find an appropriate environment—a home—where life may emerge. It is also a story of challenge that shows how lucky we are on our own planet. We see how easily worlds can be destroyed, with migrating giants and interacting young stars ejecting Earth-size objects into the void of space, or sending them spiraling into the star. It’s also a tale of triumph. Accumulated data is starting to show how common solar systems and even smaller worlds tend to be in our galaxy.

An award-winning science writer whose popular articles have been published in publications such as Scientific American and The Economist, Jayawardhana artfully blends interviews and profiles of leading researchers within his scientific narrative. Both aspects are fascinating and full of adventurous twists and turns.

If planetary systems are increasingly seen as chaotic and dangerous, such qualities might describe the enterprise of planet hunting itself. Chaotic because the nature of making observations at the limit of our equipment’s detection ability, or in which assumptions about planetary or stellar science are required, mean that there were a lot of early false starts, with lots of initial planetary candidates shown eventually not to exist.

Planet hunting was a pioneering field but also a dangerous game for those with uncertain career futures. In its early days in the 1980s there was great skepticism about whether the project was even a part of astronomy. Jaywardhana tells the story of Gordon Walker, now retired from the University of British Columbia, who watched as a senior astronomer left during a lecture he was giving on the topic. Walker’s postdoc teammate, Bruce Campbell, was compelled to leave the field for something more reliable, becoming a tax consultant. Even in the early 1990s, research groups were routinely turned down for funds, with granting agencies seeing little chance of detection improvement.

Yet, here we can see how quickly progress can be achieved in a scientific discipline. With seven planets discovered in the turning point year of 1996, everything changed. Within a mere decade planet hunters Michael Mayor and Geoff Marcy shared a major triumph, winning the prestigious million dollar Shaw Prize for astronomy in 2005, a sure sign that the field had come of age.

As Jayawardhana describes the scientific figures involved, such as Marcy and others, we see portraits of characters who are each unique and colorful, not unlike the worlds they’ve discovered. Some were portrayed with an arrogance, such as the very early character Thomas Jefferson Jackson See, who brazenly declared back in 1899 that he had found conclusive proof of a third body orbiting the binary star system 70 Ophiuchi. When a paper showed that such a system would be unstable, See rebuked the journal, which went so far as to ban him from future publication. See suffered a breakdown three years later.

The failure to relent by many researchers is nicely contrasted with the humility of Andrew Lyne, who almost achieved credit for discovering the first exoplanet in 1992. Less than a week before his scheduled talk at the American Astronomical Society, and with Nature already declaring the significance of the discovery, Lyne found an error in his data that made the planet disappear. While Jayawardhana’s depiction of this episode can show how desires might affect data analysis, this was a proud moment for science. Lyne immediately reported his error in front of a huge audience and was honored for his forthrightness.

In Strange New Worlds we come to understand that these exoplanets also demonstrate the difficulty of doing science in areas such as planet hunting that are at the limit of our equipment’s ability to discern signal from noise, and especially where human desires to see things can affect our observations. This may be exacerbated by the emotional side of searching for worlds in the hope of eventually finding other habitable homes, not unlike the well known drama of Percival Lowell and his false readings of long straight lines on Mars as evidence of artificially constructed canals and thus Martian civilization.

But considering these equipment limits, Jayawardhana shows us that it really is remarkable what we can learn about far off worlds. We can determine not just their mass, volume, and density, but sometimes we can glean details of their atmospheric constituents, with a tantalizing possibility for seeing biosignatures. We are now at the stage of detecting planets merely a few Earth masses, so-called super-Earths. As we zero in on Earth-type planets in Earth-type orbits around sun-like stars, we are led to the tantalizing hunt for Extraterrestrial Intelligence.

Unfortunately, Jayawardhana’s book is rather short, and we’re left wishing he had commented further on the second element of its subtitle, namely the search for life. Although planet hunting is only now reaching the point of giving us information directly relevant to this area of exploration, he might have shared his own speculations on how far next generation planet exploration missions could go in providing signs of life data, or on how such missions might actually integrate elements of SETI.

We’re left eager for such comments after being shown actual pictures of other worlds. The first images of exoplanets not only serve as a symbolic vindication of the search, they have the immediate emotional appeal of seeing an object that’s really there. Jayawardhana’s closing chapters leave the reader understanding that we’re only getting started and certainly just entering the most exciting part of planet hunting.

Just this February, the Kepler team announced 1,235 planetary candidates. They require confirmation, which could take up to three years, but such data, accumulated over a mere five months, could triple the number of planets already discovered. Within this batch, 68 are Earth-like in size and 54 are within their star’s habitable zone. The estimate is that six percent of stars contain Earth-size planets. This not only gives us a general understanding that there’s a lot of real estate out there, but actually provides increasingly accurate quantities for two factors in the famous Drake equation for estimating the number of signaling ETs in the galaxy, namely fp (the fraction of stars that have planets) and ne (the average number of planets that can potentially support life per star with planets).

Jayawardhana’s book offers a great and cohesive synopsis of how far the field has come and leaves the reader excited about the prospect of following along as future discoveries are made. One need not be a passive observer either. Amateur astronomers such as Jennie McCormick from New Zealand are playing a role helping to confirm exoplanets discovered by gravitational lensing. The search for exoplanets has concreteness and an emotional appeal that other astronomical fields such as cosmology or the study of galaxies or black holes may lack, and even laypeople can join in through internet-based computing projects similar to seti@home. One of these, www.zooniverse.org, has users identify transiting planets from real Kepler mission data. The idea that any member of our species with internet access could assist in the discovery of a new planet, eventually perhaps one that is habitable, is sure to keep the search for exoplanets popular and bring increased attention to the role of science in exploring the big questions of our place in the cosmos.

Skeptical perspectives on the cosmos and space exploration…

-

The Varieties of Scientific Experience

The Varieties of Scientific Experience

by Carl Sagan (edited by Ann Druyan) -

This book presents Sagan’s prestigious Gifford Lectures on Natural Theology, in which he discusses his views on topics ranging from manic depression and the possibly chemical nature of transcendance to creationism and so-called intelligent design to the likelihood of intelligent life on other planets to the likelihood of nuclear annihilation of our own to a new concept of science as “informed worship.” Sagan’s humorous, wise, and at times stunningly prophetic observations on some of the greatest mysteries of the cosmos have the invigorating effect of stimulating the intellect, exciting the imagination, and reawakening us to the grandeur of life in the cosmos. READ more and order the book.

-

Are We Alone? The Search for

Are We Alone? The Search for

Extraterrestrial Intelligence

by Dr. Thomas McDonough

-

The Crowded Universe: The Search for Living Planets

The Crowded Universe: The Search for Living Planets

by Alan Boss -

We are now nearing a turning point in our quest for life in the universe — we now have the capacity to detect Earth-like planets around other stars. But will we find any? In this lecture, renowned astronomer Dr. Alan Boss — a research scientist at the Carnegie Institution and a fellow of the American Geophysical Union — argues that based on what we already know about planetary systems, in the coming years we will find abundant Earths, including many that are indisputably alive. Life is not only possible elsewhere in the universe, Boss argues — it is common.

READ more and order the lecture.

Be sure to check out Shop Skeptic’s section of lectures on the topics of the cosmos and space exploration.

Solution to last week’s photo

The Mystery Photo from April 13th was taken in 1976 in the laboratory of Dr. Douglas Navarick, an experimental psychologist at the California State University, Fullerton who was my thesis advisor for my Master’s degree in experimental psychology, in which we ran choice experiments on rats and pigeons and recorded the data on those data sheets and processed the data through this Texas Instrument programmable calculator. Those yellow sticks were called pencils. Here is what graduate students looked like in those days (in the photograph, below-right, is my grad student colleague and now psychologist John Chelson).

Click the photos to enlarge them.

We will reveal the answer to this week’s Mystery Photo in next week’s eSkeptic.

The Latest Episode of Mr. Deity

WATCH THIS EPISODE | DONATE | NEWSLETTER | FACEBOOK | MrDeity.com

Lecture this Sunday at Caltech

Braintrust: What Neuroscience Tells Us about Morality

with Dr. Patricia Churchland

Sunday, April 24, 2011 at 2 pm

WHAT IS MORALITY AND WHERE DOES IT COME FROM? Neurophilosopher Patricia Churchland argues that morality originates in the biology of the brain: Moral values are rooted in family values displayed by all mammals — the caring for offspring. The evolved structure, processes, and chemistry of the brain incline humans to strive not only for self-preservation but for the well-being of allied selves — first offspring, then mates, kin, and so on, in wider and wider “caring” circles. Separation and exclusion cause pain, and the company of loved ones causes pleasure; responding to feelings of social pain and pleasure, brains adjust their circuitry to local customs. A key part of the story is oxytocin, an ancient body-and-brain molecule that allows humans to develop the trust in one another necessary for the development of close-knit ties, social institutions, and morality. Order the book on which this lecture is based from Amazon.com.

Ticket information

Tickets are first come first served at the door. Seating is limited. $8 for Skeptics Society members and the JPL/Caltech community, $10 for nonmembers. Your admission fee is a donation that pays for our lecture expenses.

Can’t Make it to Our Lectures?

Get them on DVD!

Many of you would love to be able to make it to our lectures at Caltech, but cannot. And, many of you may not realize that we record almost all of our lectures and sell them on CD and DVD through our online store.

Skepticality

Why We Get Fat and

What to Do About It

Each year 45 million Americans diet to lose weight, spending $33 billion on weight-loss products—and yet, 68 percent of Americans are now classified as overweight or obese. If the prescription to eat less and exercise more, or maintaing a calorie deficit is all it takes to lose or maintain a healthy weight, why are so many of us fat and getting fatter?

This week on Skepticality, Swoopy talks with award-winning science journalist Gary Taubes about his most recent book, “Why We Get Fat: And What to Do About It” which looks critically at the science of adiposity (hundreds of years of scientific research and data about the best ways to avoid obesity and obesity-related illness). Taubes also debunks the myth that losing weight is all about the calories.

MonsterTalk

Tracking the Manbeasts

Renowned investigator Joe Nickell returns to MonsterTalk to discuss his latest book Tracking the Man-beasts: Sasquatch, Vampires, Zombies, and More—a survey of a human-like monsters that runs the gamut from Almas to Zombie. The book covers scores of monsters from legend and lore, and many entries include insights from Joe’s personal investigations.