In this week’s eSkeptic:

- Cruise Update: Upgrade to a room with a view! (6 balconies available now)

- Feature article: A Skeptic Among the Cadavers

- Follow Daniel Loxton: You Have Been Poked By God

- Follow Michael Shermer: The Myth of the Evil Aliens

- MonsterTalk: Searching For Sasquatch

- Mystery Photo: Previous Photo Revealed, Plus a New Photo

- Science Symposium: Ticket and Scholarship information

Want a room with a view? Now you can have one!

UPGRADE YOUR ROOM on our Alaskan geology cruise. Due to a group cancellation, two rooms with outside windows and six balcony rooms have become available. Call Brandi at 561-204-3100 to upgrade your room today.

About this week’s feature article

Into the trenches of a rousing, blood-flecked battle in the ongoing war between good science and bad science, a new book reminds us that the stakes of the game have always been nothing less than life and death. In this week’s eSkeptic, Stephen Beckner reviews Douglas Starr’s new book, The Killer of Little Shepherds: A True Crime Story and the Birth of Forensic Science.

Stephen Beckner is a screenwriter and filmmaker. He is best known for his feature film A.K.A. Birdseye. He is currently developing a future fiction television drama on the social consequences of an anti-aging pharmaceutical. He is also working on a feature screenplay based on the (incredibly strange) life of JPL co-founder Jack Parsons.

SUBSCRIBE to Skeptic magazine for more great articles like this one.

A Skeptic Among the Cadavers

a book review by Stephen Beckner

Considering that the human brain is tricked out for pattern recognition, it might be surprising that Joseph Vacher’s pattern of stabbing, raping, and mutilating French shepherds went unrecognized for so long. Between 1893 and 1897, Vacher stalked the French countryside, butchering at least eleven people with a predation that was said to surpass the “werewolf of legends.” Although his murder-fest riveted the public and stoked the Penny Dreadfuls of his time, today it is largely forgotten. But for those of us with more than a passing interest in the struggle between good science and bad science, Douglas Starr’s Killer of Little Shepherds takes us into the trenches of a rousing, blood-flecked battle in that ongoing war, and reminds us that the stakes of the game have always been nothing less than life and death.

“Society has the criminals it deserves.”

In Starr’s attentive hands, Vacher’s case is retold as a bellwether of the nascent field of forensic science. Like the Scopes trial a quarter of a century later, the prosecution of Vacher provided plenty of tabloid drama as rival ideologies sought to turn the accused into a poster child for their cause. Was Vacher insane? Is there such a thing as a born criminal? Is society ultimately responsible for its wayward souls?

All of this held me enthralled for a particular reason. I’ve been nursing a hypothesis about the nature of evil for years. The idea is straightforward: evil doesn’t exist. There are only behaviors with good or bad consequences, and even those are highly subjective—bad for whom? Evil is what we invoke when we don’t understand something that has particularly nasty consequences. Mostly, criminals are motivated by standard-issue desires and aspirations; they’re just willing to overlook a rule or two to achieve them. But when bad behavior falls outside the parameters of normal self-interest, when the motivation escapes even our wildest projections, we retreat to that stand-in for everything and nothing—evil.

Vacher is such a case. “Evil incarnate” is one of the clichés that springs to mind when stories like Vacher’s are recounted, but as Starr’s book suggests, such moral epithets have hindered the advancement of criminology. If you want to learn what makes bad guys/gals tick, there are better ways than calling them names. But you might have to dig around in a corpse or two to get some answers.

The Pattern

If Joseph Vacher ever had a shot at a normal life, he blew it when he aimed a gun at his own head and pulled the trigger—twice—after attempting the same with Louise Barant, the pretty young object of his unrequited amour fou. Vacher’s wounds left his face disfigured, and a bullet permanently camped out behind one ear. Curiously, after regaining his strength he was remanded, not to prison to await trial as one might expect, but to an asylum. More curious still, his history of violence failed to make the journey with him, and within a few months his doctors pronounced him cured and released him—though “unleashed him” might be the more appropriate phrase.

Over the next few months, a pattern began to emerge, one that would eventually be repeated throughout France: a lone boy or girl near the edge of a forest or guarding livestock in an isolated pasture was approached from behind. Choked. Throat cut. Dragged away. Skirts hiked. Trousers ankled. Defiled. Mutilated. Body hidden. And almost always, another pattern in its wake: villagers angry, authorities dumbfounded, mobs formed, local scapegoats accused and vilified, the real killer never found. In four years, Vacher had dotted the map of France with his bucolic horrors. And those dots were itching to be connected.

The Scientists

Dr. Alexandre Lacassagne was a collector. He collected the skulls and tattoos of criminals from all around France. He recorded blood spatter from crime scenes and collected them in his highly regarded Archives of Criminal Anthropology. He was always looking for patterns in those collections. A pioneer in crime-scene analysis, Lacassagne developed techniques to match bullets to guns and determine time of death. He standardized autopsy procedures across France. His interests took him beyond the crimes themselves, and into criminal culture. He spent hours interviewing noted criminals, and convinced many to write confessional autobiographies for scientific study. His postmortems were literally attempts to get into the heads of criminals. His was a career devoted to understanding why some people break bad. And it’s here, on the subject of the breaking bad that Starr’s book takes flight, because the real drama of the story comes from the battle between Lacassagne and the superstitions posing as science in the field of criminology at the time.

Broadly speaking, theories of criminogenesis can be said to have moved from the notion of crime as sin toward the notion of crime as disease. Early societies believed that the forces of evil, such as demonic possession, gave rise to criminal behavior. Judeo-Christian traditions hold that since God is the source of morality, sin—in the form of crime—must have satanic origins.

These ideas were little more than superstitions, but they went largely unchallenged until the mid 17th century, when social philosophers began to think of the criminal in a social context. To men like Jeremy Bentham, man was a rational, calculating being, constantly weighing the utility of one potential action against another. Only when the negative consequences of criminal behavior outweigh the benefits do human beings opt for the straight and narrow. But this description seemed insufficient for fiends like Vacher. By what standard could his gory enterprise be interpreted as rational?

Cesare Lombroso did not trouble himself with such questions. According to the Italian criminologist, some people were born criminals. These “atavistic” creatures were a genetic throwback, a subspecies of human beings that could be identified by certain physical “stigmata,” such as a jutting jaw, a broad flat skull cap, asymmetry, long arms, and sloping shoulders. By the 1890s Lombroso’s “Italian School” of criminal anthropology had gained worldwide acceptance. Lacassagne bitterly opposed Lombroso’s conclusion that biology was destiny. He insisted that environment played a critical role in determining criminal behavior. The criminal was a “germ” that could only thrive in the “broth” of society. Between Lacassagne and Lombroso, the stage was set for perhaps the earliest skirmish in the modern nature/nurture debate.

The Mind of a Murderer

Starr dedicates a good portion of his book to Vacher’s trial. Shortly after his arrest, Vacher claimed insanity and began a surprisingly clever campaign for another, hopefully short, stay in an asylum. He would be the first serial killer to claim no legal responsibility for his crimes. This is what worried Lacassagne. At that time, there were no prisons for the insane, and asylums were not set up to contain dangerous criminals.

The key point of inquiry during the proceedings was Vacher’s state of mind. Vacher blamed everything but himself; a rabid dog once bit him, he had a bullet in his head, his doctors never should have let him out of the asylum. Lacassagne found himself torn between his conviction that society has the criminals it deserves, and his obligations as a public official to serve what he said was society’s “right to defend itself.” He knew that Vacher could not be allowed back into society, but if he truly believed that society was partly responsible for criminals like Vacher, how could he then argue for his death? He needed another option, and he found it in the relatively new field of psychology. Taking the stand, he claimed that Vacher suffered from Sadistic Personality Disorder. No, he was not insane, Lacassagne explained, merely unable to separate his anger from his sexual urges. Crucially, the “systematic nature” of the crimes demonstrated to Lacassagne that reasoning was involved. It was the pattern of the crimes that proved Vacher’s responsibility, a pattern that, as far as Lacassagne was concerned, should end with Vacher’s neck in a guillotine.

Criminologists debated Vacher’s sanity long after his death. But in the days when so little was known about the workings of the mind, what did the term insanity really mean? I would argue that it amounted to a secularized version of evil, another shelf to hide away the things we do not understand. With his testimony, Lacassagne gave the judge a way to understand the mind of Vacher. Before his guillotinage, competing ideological camps staked out claims on Vacher’s brain for dissection. Vacher even cut a deal attempting to prevent Lacassagne from any postmortem access, but in the end everyone with a dog in the hunt got their piece of Vacher. Nothing was ever found to establish a biological cause for the killer’s urges.

Of Science and Moral Prejudice

But the man had hereditary tendencies of the most diabolical kind. A criminal strain ran in his blood, which, instead of being modified, was increased and rendered infinitely more dangerous by his extraordinary mental powers.

That could be Cesare Lombroso talking about Vacher. It’s actually Sherlock Holmes on the subject of Professor Moriarty. The quote reflects the popular appeal of Lombroso’s ideas at that time. But Lombroso was wrong. There is no reliable link between physiognomy and criminality, or between criminality and heredity. By all accounts, there was more confirmation bias in Lombroso’s methods than there were Spiritualists on the guest lists for dinner at the Conan-Doyle’s, but then as now, logic is no match for an idea that’s really dialed- in to our fears and prejudices.

Starr, a veteran science reporter, is almost painfully generous with Lombroso, however, insisting that he was sincerely trying to understand criminality in the context of the then new science of evolution. A less kind, but possibly more accurate antecedent to Lombroso’s theories is phrenology. Why Starr relegates it to a footnote isn’t clear, but the omission is unfortunate. If evolution is the father of criminal anthropology, then phrenology is its midwife. It’s also a missed opportunity to explore how even terrible science can sometimes be useful as a stepping-stone to better science. Both Lombroso and Lacassagne accepted, and then eventually rejected phrenology, each taking a piece of it into their own theories.

To my way of thinking, the anthropological otherness Lombroso ascribes to the criminal type is the successor of that age-old notion of evil, now decked out in the authoritative language of science. This tendency persists today. Even the psychiatrist M. Scott Peck—whose book People of the Lie: The Hope For Healing Human Evil attempted to methodically break down the “evil person” into its working parts—struggled to describe evil outside the framework of Christian sin. I would like to think that the work of researchers such as Stanley Milgram (of shock experiment fame) and Philip Zimbardo (of Stanford prison experiment fame) would have slammed the door on our superstitions and prejudices about lawless behavior—showing as they did how easy it is to get ordinary people to commit extraordinary acts of “evil” just by obedience to authority and other social psychological factors—but even now scientists busily scan the amygdales of prisoners for the ultimate mark of the beast, and Lombroso’s totemic “born criminal” remains a chart-topper in the popular imagination.

Starr does more than dabble with these complex ideas, but he never lets you forget that this is a book about forensics. Covering the territory between Grand Guignol and CSI, Starr lingers on the forensic details of the story, and no detail is too gruesome. The reader’s morbid curiosity will be amply satisfied with such delicacies as the discovery of a signature progression of voracious insect varieties that tag-team a corpse and date the death by their specific presence (a warning: blowflies are at the top of that food chain); or the art of autopsy before the age of refrigeration, when doctors made pinpricks in cadavers and lit them in order to burn off the gases of putrefaction.

Although the Lacassagne School of criminality had its moment in the spotlight, it was eventually overshadowed by broader theories of social determinism popular in the early 20th century. Lacassagne’s contributions to forensics have enjoyed a more lasting influence, and above all, Starr makes a convincing case that Lacassagne should be regarded as the father of modern forensic science. Our forensic toolbox may have more bells and whistles than before, but forensic methodology is fundamentally unchanged since Lacassagne’s day. So the next time you’re looking for clues at the scene of a crime, don’t think Holmes or Poirot, think Alexandre Lacassagne.

Skeptical perspectives on morality and the science of human values…

-

The Science of Good & Evil

The Science of Good & Evil

by Michael Shermer

-

The Lucifer Effect

The Lucifer Effect

Dr. Philip Zimbardo

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

You Have Been Poked By God

In this week’s Skepticblog, Daniel Loxton recounts persuasive and personal paranormal experiences of skeptical pioneers Isaac Asimov and James Randi and reminds us of just how understandable, even natural, it is for smart people to believe weird things.

NEW ON MICHAELSHERMER.COM

The Myth of the Evil Aliens

WITH THE ALIEN TELESCOPE ARRAY run by the SETI Institute in northern California, the time is coming when we will encounter an extraterrestrial intelligence (ETI). Contact will probably come sooner rather than later because of Moore’s Law (proposed by Intel’s co-founder Gordon E. Moore), which posits a doubling of computing power every one to two years. What will happen when we do, and how should we respond?

Searching For Sasquatch

Is cryptozoology science or pseudoscience? Do scientists ever really study cryptozoology, or merely ignore the field entirely? This week we dig into the history of Cryptozoology itself—focusing on the search for America’s most famous cryptid: Sasquatch. This week on MonsterTalk, we’re joined by Dr. Brian Regal to talk about his latest book, Searching For Sasquatch: Crackpots, Eggheads and Cryptozoology.

Solution to last week’s Mystery Photo

The Mystery Photo from June 1st is the psychic palm-reading shop in Oakland, California, right next door to Harold Camping’s Family Radio offices, and upstairs from a hamburger joint. Is this the all-American set up? An open strip mall that features an end-of-the-world preacher, a psychic palm reader, and a burger joint. Perfect.

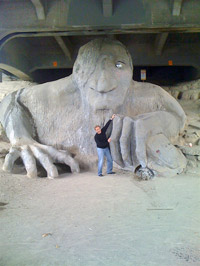

This week’s Mystery Photo

Where in the world is this trollish creature?

We will reveal the answer to this week’s Mystery Photo in next week’s eSkeptic.

Everyone Welcome

Don’t miss this rare opportunity to hear four of the world’s leading Skeptics discuss their experiences fighting irrationality and promoting science (and what you can do to help)!

Student Scholarships

Full-time college or high school students can apply for a scholarship to attend the Symposium on Saturday, June 25, 2011. Breakfast, lunch and dinner are included; travel and lodging are not included. For high school student scholarship winners, we’ll also cover the entry fee for one chaperone per group of ten students.