In this week’s eSkeptic:

Viva Mojave!

JOIN THE SKEPTICS SOCIETY FOR A WONDERFUL THREE-DAY TOUR of the highlights of the Mojave Desert and the Las Vegas area. We will stop at the historic restored ghost town of Calico and take several tours, visit Afton Gorge where Ice Age floods drained Lake Manix, collect 550 million year old trilobites, experience the spectacular boulders of Red Rock Canyon, and conclude with a guided tour of Hoover Dam. The Hoover Dam tours are not recommended for anyone who suffers from claustrophobia, or has a pacemaker or defibrillator. Tours are conducted in confined spaces and in a powerplant with generators emitting electromagnetic frequencies. Those who can not participate in the tour may enjoy the visitor’s center. Each night we will stay at the Excalibur Hotel on the Las Vegas Strip, where you can explore Sin City on your own.

Click an image to enlarge it.

What’s Included?

Tour price includes charter bus, all hotel accommodations, breakfast and lunch each day, guided tour narration and guidebook, all other admission fees, and a tax-deductible contribution to the Skeptics Society. Seats are limited to about 50 people on a single tour bus, so the tour should fill up fast.

Questions?

Email us or call 1-626-794-3119 with a credit card to secure your spot.

Download complete details and registration form for Viva Mojave!

Whale Watching, Geology and Tide Pools

We have about 12 spots left on our 1-day whale watching tour coming up on November 12, 2011. Highlights include: a morning whale watching cruise on a boat reserved just for us, a tour of the Cabrillo Marine Aquarium, a marine biology lecture with special emphasis on tide pools, and a visit to some of the geologic highlights of the Palos Verdes Peninsula (including Portuguese Bend Landslide).

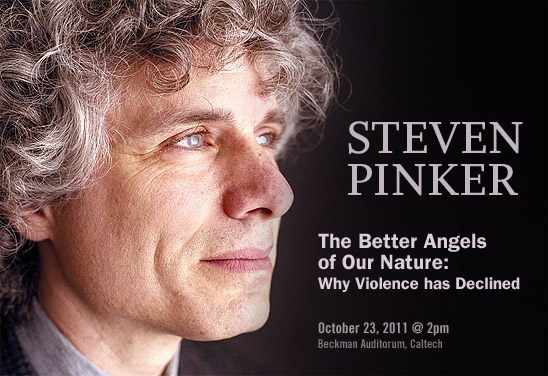

See Steven Pinker this Sunday!

The Better Angels of Our Nature:

Why Violence has Declined

Sunday, October 23, 2011 at 2 pm

BECKMAN AUDITORIUM

“Steven Pinker’s new book, The Better Angels of Our Nature, is one of the most important science books I have ever read, and in my opinion may very well be one of the most important science books ever written. Period. It is a stunning piece of research and an epic masterpiece of narration and storytelling. It is nearly 800 pages long and I’ve already read it twice. It’s that good.”

Harvard University psychologist and New York Times bestselling author Steven Pinker shows in this startling and engaging new work that violence has been diminishing for millennia and that we may be living in the most peaceful time in our species’ existence…

Tickets are $10 Skeptics Society members/Caltech/JPL community; $15 everyone else. Tickets may be purchased in advance through the Caltech ticket office at 1-626-395-4652 or at the door. Ordering tickets ahead of time is strongly recommended. The Caltech ticket office asks that you do not leave a message. Instead call between 12:00 and 5:00 Monday through Friday.

NEW ON MICHAELSHERMER.COM

The Flake Equation

Modelled after the Drake Equation—the famous formula developed by the astronomer Frank Drake for estimating the number of extraterrestrial civilizations—Michael Shermer created the Flake Equation for estimating the number of people we hear about who report having had a paranormal or supernatural experience. Such multiplicative equations for calculating the product of an increasingly restrictive series of fractional values are effective tools for making back-of-the-envelope calculations to solve problems for which we do not have precise data. As you will see, the Flake Equation goes a long way toward explaining why belief in the paranormal and supernatural is so ubiquitous. Experiencing is believing!

The Latest Episode of Mr. Deity: Mr. Deity and the Naughty Bits

WATCH THIS EPISODE | DONATE | NEWSLETTER | FACEBOOK | MrDeity.com

“It is ironic that the United States should have been founded by intellectuals, for throughout most of our political history, the intellectual has been for the most part either an outsider, a servant or a scapegoat.”

An Excerpt from Nonsense on Stilts:

How to Tell Science from Bunk

In this week’s eSkeptic, we present an excerpt from Massimo Pigliucci’s book Nonsense on Stilts: How to Tell Science from Bunk in which he discusses the alleged decline of the public intellectual, especially in the United States, as well as at the parallel ascent and evolution (some would say devolution) of so-called think tanks. He treats both as rather disconcerting indicators of the level of public discourse in general, and of the conflict between science and pseudoscience in particular. It is an area that is both usually neglected within the context of discussing science in the public arena and yet crucial to our understanding of how science is perceived or misperceived by the public. This excerpt appeared in Skeptic magazine volume 16, number 1 (2010).

Science by Think Tank

The Rise of Think Tanks and

the Decline of Public Intellectuals

by Massimo Pigliucci

Are public intellectuals in the 21st century an endangered species or a thriving new breed? Before we can sensibly ask whether public intellectuals are on the ascent, the decline, or something entirely different, we need to agree on what exactly, or even approximately, constitutes a public intellectual. It turns out that this isn’t a simple task and that the picture one gets from the literature on intellectualism depends largely on what sort of people one counts as “public intellectuals,” or, for that matter, what sort of activities count as intellectual to begin with. Nonetheless, some people (usually intellectuals) have actually spent a good deal of time thinking about such matters and have come up with some useful suggestions. For example, in Public Intellectuals: An Endangered Species? Amitai Etzioni quotes the Enlightenment figure Marquis de Condorcet to the effect that intellectuals are people who devote themselves to “the tracking down of prejudices in the hiding places where priests, the schools, the government and all long-established institutions had gathered and protected them.”1 Or perhaps one could go with the view of influential intellectual Edward Said, who said that intellectuals should “question patriotic nationalism, corporate thinking, and a sense of class, racial or gender privilege.”2

Should one feel less romantic (even a bit cynical, perhaps) about the whole idea, one might prefer instead Paul Johnson, who said that “a dozen people picked at random on the street are at least as likely to offer sensible views on moral and political matters as a cross-section of the intelligentsia.”3 Or go with David Carter, who wrote in the Australian Humanities Review that “public intellectuals might be defined as those who see a crisis where others see an event.”4

Regardless of how critical one is of the very idea of public intellectualism, everyone seems to agree that there are a few people out there who embody— for better or worse—what a public intellectual is supposed to be. By far the most often cited example is the controversial linguist and political activist Noam Chomsky. Indeed, his classic article “The Responsibility of Intellectuals,” written in 1963 for the New York Review of Books, is a must-read by anyone interested in the topic, despite its specific focus on the Vietnam War (then again, some sections could have been written during the much more recent second Iraq War, almost without changing a word).5

For Chomsky the basic idea is relatively clear: “Intellectuals are in a position to expose the lies of governments, to analyze actions according to their causes and motives and often hidden intentions…. It is the responsibility of intellectuals to speak the truth and to expose lies.”6 Yet one could argue that it is the responsibility of any citizen in an open society to do just the sort of things that Chomsky says intellectuals ought to do, and indeed I doubt Chomsky would disagree. But he claims that intellectuals are in a special position to do what he suggests. How so? It is not that Chomsky is claiming that only genetically distinct subspecies of human beings possess special reasoning powers allowing them to be particularly incisive critics of social and political issues. Rather, it is that intellectuals—at their best—are more insightful in social criticism because they can afford to devote a lot of time to reading and discussing ideas—something that most people trying to make a living simply do not have the time or energy to do. Moreover, intellectuals have a duty to be so engaged with society because often their vantage point is the result of a privileged position granted them by society, most obviously in the case of academic intellectuals (but also journalists, some artists, and assorted others), who are somewhat shielded from most direct political influence or financial constraints, and whose professional ethos requires intellectual honesty and rigor. Of course, none of this guarantees that public intellectuals always get it right, or that they always further the welfare of society. The classic counter- example, mentioned by Chomsky himself, is the philosopher Martin Heidegger.

Heidegger is a controversial figure, to say the least, both academically and politically (not unlike Chomsky himself, though the similarity ends there). Some commentators consider him one of the greatest of modern philosophers; others think that his writings are full of obfuscatory language and sheer nonsense. He was the mentor of Leo Strauss—who in turn inspired the modern neoconservative movement—as well as the father of several movements that feature prominently in the “culture wars,” such as deconstructionism and postmodernism. At any rate, Heidegger was elected rector of the University of Freiburg in Germany in 1933, under the auspices of the Hitler regime. The inaugural address he delivered is in fact a good example of convoluted nonsense, and it just as clearly represents the exact antithesis of what a public intellectual should be.

After having waxed poetic about spiritual missions and the “essence” of German universities, Heidegger went on to say that “German students are on the march. And whom they are seeking are those leaders through whom they want to elevate their own purpose so that it becomes a grounded, knowing truth,” a rather ominous presage of things to come for the German youth. And he kept going: “Out of the resoluteness of the German students to stand their ground while German destiny is in its most extreme distress comes a will to the essence of the university…. The much-lauded ‘academic freedom’ will be expelled from the German university.”7 Heidegger’s connection with the Nazis will forever taint his legacy, making him a permanent warning to aspiring public intellectuals about what route not to follow.

Chomsky, on the other hand—in a prose infinitely clearer and more compelling than Heidegger’s —raises the question of what the duty of an intellectual ought to be, and answers that she has to be concerned with the creation and analysis of ideologies, including those endorsed or produced by intellectuals themselves. Since the public intellectual, according to Chomsky, has to insist on truth, she also has to see things in their historical perspective, truly to learn from history rather than be bound to repeat the same mistakes over and over. Of course, the whole concept of “truth,” and by implication the efficacy of both science and of intellectual discourse, has been questioned by those academic heirs of Heidegger known as postmodernists. Setting that aside for a moment, however, there are in fact other ways of being skeptical of the whole idea of public intellectualism, for example in the analysis of Richard Posner, author of Public Intellectuals: A Study in Decline.8

Posner was a professor at the University of Chicago Law School and later became a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals (Seventh Circuit), to which he was nominated by President Reagan. By all accounts, Posner is considered a major and influential legal theorist. Despite being a highly regarded intellectual, his analysis of intellectuals as a breed is anything but sympathetic, although he makes several interesting points that we need to consider while attempting to put together a general picture of intellectualism and how it relates to public understanding of science. Posner, by his own account, wrote his book as a result of what he perceived as the low quality of public intellectuals’ commentaries in two high-profile cases in which he was involved: the impeachment hearings of President Clinton and the antitrust case against Microsoft. Posner’s thesis is that there has indeed been a decline of intellectuals in the United States, but that this isn’t a matter of fewer of them being around. On the contrary, the “market” for intellectualism has allegedly increased dramatically in recent years, but the quality of the individuals populating such a market has decreased sharply.

Posner accounts for this double trend (increase in quantity and decrease in quality) with an ingenious, if certainly debatable, analysis of some of the forces shaping both the supply of and the demand for public intellectuals. On the supply side, intellectuals are now almost exclusively an academic phenomenon. Gone are the days of Zola and (Anatole) France, when it was the independent artist or writer who was more likely to be outspoken about social matters. Instead, the rise of universities (in terms of both numbers and financial resources) after World War II has catalyzed a shift toward academic-type intellectuals. Academics are better positioned than independents to play a role in public discourse because they are more readily perceived as credentialed individuals, and they can afford to stick their neck out about controversial matters in the relative safety of a tenured position.

Not that all is good and well for academics who wish to venture in the public arena. As Posner points out, there are pros and cons that need to be carefully evaluated. On the side of incentives there is the possibility of monetary reward (academic salaries aren’t what they used to be), though it is fairly rare that an academic actually lands a major book contract or is in sufficient demand to command significant honoraria for speaking engagements.

On the side of disincentives, there are several, some potentially career-crippling. To begin with, the more time an academic devotes to speaking and writing for the public, the less time she has to engage in scholarship and research—and it is the latter that gets you tenure and promotions, which helps explain why most public academics are middle aged, post-tenure, and possibly past their intellectual prime. Moreover, the myth of the ivory tower is anything but a myth: despite occasional protestations to the contrary, most academics themselves see engaging the public as a somewhat inferior activity, sought after by people who are vain, in search of money, not particularly brilliant scholars, or all of the above. According to Amitai Etzioni, after his death astronomer and science writer Carl Sagan was referred to as a “cunning careerist” and a “compulsive popularizer”—not exactly encouraging words for other scientists considering following in his footsteps.9

Posner also turns his analysis to the other side of the coin, looking into what sort of demand there might be for public intellectuals. He suggests that there are at least three “goods” that public intellectuals may be “selling,” and that therefore influence the level of “demand” for intellectuals themselves. Besides the obvious one, that is, presumably authoritative opinions on current issues of general relevance, there are what Posner calls “entertainment” and “solidarity” values.

There is little question that we live in a society in which entertainment, broadly defined, reigns supreme. The nightly news, not to mention the 24- hour news channels, are increasingly less about serious journalism and more about sensationalism or soft news, so much so that one can make a not entirely preposterous argument that The Daily Show with Jon Stewart is actually significantly more informative than the real news shows that it is meant to spoof. As biologist Richard Dawkins lamented,10 we think that our kids need to have “fun, fun, fun” rather than, say, experience wonder or interest (they are not the same thing) when going to school or a museum. It is therefore no surprise that even intellectuals have to possess an entertainment value of sorts, although it is of course difficult to quantify it and its effect, if any, on the demand for public intellectuals. Such effect will also depend greatly on the specific media outlet: while there are plenty of TV channels and newspapers for which the entertainment value is probably close to the top of priorities, there are still serious media outlets out there (BBC radio and TV, National Public Radio, Public Television, the New York Times, the Washington Post, The Guardian, The Economist, Slate.com, and Salon.com come to mind, among many others) where the relevance and insight of what the intellectual has to say are paramount.

We come next to the concept of “solidarity value” proposed by Posner. This is often underestimated, but I suspect it does play an increasingly important (and, unfortunately, negative) role in public discourse. The idea is that many, perhaps most, people don’t actually want to be informed, and even less so challenged in their beliefs and worldview. Rather, they want to see a champion defending their preconceived view of the world, a sort of ideological knight in shining armor. Blatantly partisan outlets such as Fox News (on the right), Air America (on the left), and the countless number of Evangelical Christian radio stations are obvious examples of this phenomenon, but perhaps the most subtle and pernicious incarnations of it are all over the Internet. The characteristics of that medium are such that it is exceedingly easy to customize your access so that you will only read what people “on your side” are saying, never to be exposed to a single dissenting viewpoint. While blogs, for example, are indubitably a revolutionary and potentially very powerful way to expand social discourse, it is also very easy to bookmark or subscribe by feed to a subset selected in order to further entrench, rather than challenge, your opinions.

All things considered, Posner’s arguments point toward a level of supply and demand for public intellectuals that translates into a larger number of them than probably at any time in history. But, of course, quantity is rarely an indication of quality, which brings us to Posner’s contention that the decline of the intellectual is a matter of lowered quality. There are fundamentally three reasons for this conclusion, all of which are circumstantial, as it is very hard to assess the quality of public intellectual discourse in any objective and statistically quantifiable way. We have already seen the first reason: since intellectuals are sought after at least in part for their entertainment and solidarity values, and given that neither of these is presumably related at all to the degree of insight offered by the opinions being delivered, quality is liable to suffer.

The second reason advanced by Posner is the inevitable march of academia toward increased specialization of its scholars. Remember that most modern intellectuals are academics, and they are successful within academia because they specialize in incredibly narrow fields of scholarship and research— since most of the broad ones have already been covered exhaustively by their predecessors. For example, the joke used to be that philosophers are people who know nothing about everything (they are intellectual generalists), while scientists know everything about nothing (they are intellectual specialists). But in today’s universities, even philosophers are converging toward the stereotype of the scientist: I know colleagues in philosophy departments who spend a lifetime publishing analyses of the work of just one (usually long-dead) philosopher, and often not a major one at that. Similarly, some of my colleagues in science think it absolutely crucial to invest many hundreds of thousands of dollars and countless graduate-student years to figure out whether an obscure species of mushroom is by any chance found also in Antarctica. This is the way it must work if one wishes to contribute something truly novel to one’s field.

Finally, there is the failure of the so-called marketplace of ideas, which Posner is one of the few to keenly recognize. The phrase originated with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, who wrote the dissenting opinion in the infamous Abrams v. United States case argued in 1919 in front of the Supreme Court that was a test of a law passed the year before that made criticism of the U.S. government a criminal offense. The law was upheld, and the statute not invalidated until Brandenburg v. Ohio, during the Vietnam War. Holmes wrote passionately about the safeguard for freedom of speech enshrined in the American Constitution, arguing that “the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas—that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which [men’s] wishes safely can be carried out. That at any rate is the theory of our Constitution.” Holmes was correct in suggesting that a necessary condition for maximizing our chances to find the truth about whatever subject matter or for reaching a consensus on moral and social issues is to allow ideas to “compete” for people’s minds and hearts.

Posner’s point is that this is by no means a sufficient condition. There is need of a second factor in addition to the free marketplace of ideas, and this is that for the best ideas to win the competition the judges must be, well, competent. But the judges here aren’t indisputable facts that can be verified by anyone; they are the opinions of a generally badly informed and undereducated (with respect to the relevant issues) public. This is a public that has little time for the sort of in-depth analyses and research that would allow it to actually assess the contributions of intellectuals on their merit. Ironically, this is precisely why Chomsky says that it is up to intellectuals, not the public, to do the hard work of research and documentation. The problem, Posner suggests, is that the public tends to go by much less reliable proxies of quality, such as credentials (but, really, it isn’t that difficult to get a Ph.D., even from a reputable university) and the rhetorical abilities of the intellectuals themselves.

There is much to be commended in Posner’s analysis of the decline of the modern intellectual, and yet one cannot help thinking that it is somewhat self-destructive for intellectuals such as Posner to be so critical of their own role in society. A good reality check is a positive and necessary part of public as well as academic discourse, but an exceedingly negative attitude soon breeds contempt for intellectual discourse itself and a nihilistic dismissal of it.

A more positive approach to the analysis of contemporary intellectualism is perhaps provided by Frank Furedi in his Where Have All the Intellectuals Gone? which starts out not with self-criticism, but with ridiculing politicians in charge of public education, namely, the then Labour secretary of state for education in the UK, Charles Clarke. Clarke characterized the idea of education for its own sake—the very foundation of the so-called liberal educational approach common in modern universities—as “dodgy,” which can be interpreted to mean anything from dishonest and unreliable to potentially dangerous. Clarke’s opinion is that the government should not support “the medieval concept of a community of scholars seeking truth.”11 Along similar lines, former U.S. President Ronald Reagan infamously said during his campaign for governor of California in the late 1960s that universities should not subsidize intellectual curiosity.

Of course Furedi is fully cognizant of the fact that a liberal education, just like the idea of a fearless public intellectual, is an ideal and has never corresponded to a historical reality at any point in the past. But it makes a big difference in terms of attitudes and motivations whether we consider an ideal a goal to strive for or we dismiss it as irrelevant, outdated, or even positively dangerous.

While Furedi devotes some space to blaming postmodernism for the decline of intellectualism, a more intriguing observation is that intellectualism is on the retreat just at the time we keep hearing of a “knowledge economy” and when bookstores, book clubs, poetry readings, museums, and galleries are doing increasingly well, to the point of having a single TV show in the United States (The Oprah Winfrey Show) determining which book will become the next overnight bestseller. Yet this apparent paradox is actually explainable by the same distinction that Posner made about intellectuals themselves: quantity does not necessarily translate into quality. While bookstores are increasingly popular, there are basically only two or three major chains left in most parts of the United States (and at least one of them is rumored to be close to bankruptcy), which means that a small number of individuals wields a huge amount of decision power when it comes to which books to promote and which to relegate to the back shelves or even keep out of the store (and, largely, off the market). Winfrey, to her credit, has almost singlehandedly made the rather esoteric and somewhat snobbish idea of a book club one of the most popular activities engaged in by scores of Americans. Then again, some of her picks have been embarrassing, as in the infamous case of James Frey (author of A Million Little Pieces), who turned out to have made up large parts of his allegedly autobiographical story (Winfrey eventually challenged him on her show, but her initial response was that he may have been telling a subjective truth—a perfect postmodernist and nonsensical way of saving face).

Furedi identifies another culprit in the ongoing quest for the disappearance of the public intellectual: the assault on meritocracy. Americans in particular have always had a rather bipolar attitude toward meritocracy: on the one hand, the United States was established by people whose very creed included the idea that it is merit, not birthright, that ought to determine one’s fortunes. American bookstores abound with large sections of books written by successful people telling others how to become successful, and American CEOs and sports figures are lionized because of their merits, not because of their family trees. Then again, one of the reasons Al Gore lost the 2000 presidential election against George W. Bush is because Gore was seen as an “egg-headed intellectual,” obviously an insult, not a compliment.

Furedi’s take is that over the past several decades the very conception of meritocracy has shifted from a powerful incentive paving the way to a fairer society to an intrinsically anti-egalitarian and undemocratic tool of oppression. The reasons for this are many and complex, and they include the rise of new philosophies of teaching within education departments at colleges throughout the nation, as well as the recognition of the sociological fact that certain minorities tend to be at a disadvantage in our meritocratic system as presently constituted (this is not, obviously, a point in favor of biological racism, but a concession to the real difficulties in overcoming cultural conditions and in creating a true level playing field).

Furedi proposes the bold thesis that the currently entrenched rejection of meritocracy is based on two mistaken ideas: first, that a large section of the population is somehow intrinsically incapable of achieving high academic standards; and second, that this failure leads to mental distress, and therefore it is appropriate to substitute “feeling good” for actual results. This is a recipe for disaster, because, as Furedi puts it, “Rewarding merit implies treating people as adults, whereas magicking away the sense of failure is motivated by the desire to treat them as children.”

Think-Tankery: From Intellectualism to Spindoctorism?

Think tanks are now pervasive worldwide: according to Diane Stone, as of the year 2000 there were 4,000 think tanks active in nations across the globe,12 and that number—very likely a gross underestimation— has certainly gone up since. Despite their number and prominent daily presence in the news, there aren’t that many sociological studies of think tanks, and even fewer critical analyses of their role in shaping public opinion. Indeed, there is not much agreement on what, exactly, defines a think tank to begin with.

For the purposes of this discussion, I will use the term “think tank” to refer to a specific kind of organization, namely, a private group, usually but not always privately funded, producing arguments and data aimed at influencing specific sectors of public policy. This definition, therefore, does not apply to most advisory groups established by a given government, nor to university institutes or centers, nor to groups set up to resolve specific problems within the normal operation of a corporation. Although I am generally skeptical of think tanks as a concept, and very critical of the operation of specific ones, I do not mean to imply that all think tanks are useless or pernicious, nor that the general idea cannot in principle be pursued in an honest and constructive fashion. But I am struck by how little critical evaluation of the phenomenon there seems to be, both in the literature on think tanks and more importantly by the media and politicians who are the primary direct consumers of think tanks’ output.

Donald Abelson gives a useful historical perspective on think tanks.13 According to Abelson, the concept went through four relatively distinct phases since its inception about a century ago. The first generation of think tanks appeared in the early 1900s and was the product of the preoccupation of a small number of rich entrepreneurs concerned with the necessity of providing sound, rational advice to the government at a time of increasing complexity of both domestic and foreign policy problems. Thus, people like Carnegie and Rockefeller provided large permanent endowments to these groups, which made them essentially independent from government support (and, therefore, influence) as well as freed them from the necessity of continuously raising private money (again emancipating them from possible leverage by their donors).

That is how groups like the Brookings Institution and the Russell Sage Foundation came about. They operated according to a model of a “university without students,” attracting scholars from across the political spectrum, sharing the ideal (if not necessarily the practice) that reason reaches across ideologies. The results of these efforts were significant in shaping American society during most of the 20th Century, for example, producing a national budget system as well as studies on the causes of warfare.

The second phase of think tank history began after World War II, when the government realized the importance of supporting scientific research because of its obvious relevance to all things military. The National Science Foundation (not a think tank) was established then, and so were think tanks like the RAND (Research and Analysis) Corporation. This is the first worrisome development in the evolution of think-tankery, since it obviously created a direct link between the funding source (in this case the government) and the recipient of research outcomes and policy advice (also the government), thus violating the intentions of the people who established the first think tanks earlier in the century.

Be that as it may, a few decades later we witness another change in concept, with the appearance in the 1970s and 1980s of what Abelson calls “advocacy think tanks.” These are groups like the progressive Institute for Policy Studies and the Center for American Progress, the libertarian Cato Institute, and the conservative Heritage Foundation. These think tanks tend to be significantly smaller than their predecessors, are dependent on continuous support by a large number of relatively small donors, and, more importantly, they often (though not always) blatantly blur the lines between research and advocacy. It is hard to read a “report” from some of these outlets and not think that their “conclusions” were actually the premises from which the whole exercise started, a definite departure from the model of a university—with or without students.

This is apparently an open secret, as the director of a major policy institute told Abelson: “[Think tanks] are tax-exempt cowboys defying the sheriff with their political manipulations. They don’t want to stimulate public dialogue, they’re out to impose their own monologue.”14 Or as Leila Hudson put it: “These institutions have substituted strategy for discipline, ideological litmus tests for peer review, tactics and technology for cultures and history, policy for research and pedagogy, and hypotheticals for empiricals.”15 Another problem intrinsic to the modus operandi of think tanks was best summarized by an anonymous official quoted in an article entitled “On Mediators: Intellectuals and the Ideas Trade in the Knowledge Society,” by Thomas Osborne: “One of the dilemmas of think tankery is that you can either say something sensible, practical and useful and have six civil servants and their dog read it, or you can say something spectacularly silly and have the media cover it.”16 None of these quotes sounds exactly like ringing endorsements of the idea of think tanks.

The last development in think tank evolution is what Abelson calls “vanity think tanks.” These are even smaller and more ephemeral operations, often set up by individuals in pursuit of short-term political goals, like Ross Perot’s United We Stand or Newt Gingrich’s Progress and Freedom Foundation. I will not examine these any further because they are only marginally relevant to science, if at all, although they have demonstrated their ability to affect the outcome of elections, and therefore— indirectly—to influence science funding and education.

What has this to do with science? It is think tanks like the American Enterprise Institute that have the gall to bribe scientists so that they speak critically of reports about global warming, and it is the anti-evolution Discovery Institute, a think tank out of Seattle, that is guided by a mandate founded on “a belief in God-given reason and the permanency of human nature,” rather than on the serious examination of scientific theories such as evolution.

Alina Gildiner goes into some detail about how think-tankery concerning science dovetails into spindoctoring rather than rigorous analysis of the problem at hand.17 Gildiner quotes Laura Jones, whose edited book on risk management has been published by a think tank, the Fraser Institute, as stating—without any data to back the claim up— that “zealous anti-risk activists have heightened our intolerance for small risks,” such as the number of deaths resulting from wheels detaching from transport trucks that were poorly maintained (in Canada, government regulation lowered that number from 215 in 1997 to 86 in 2000, and of course the statistics do not include people who got injured, sometimes seriously, from collisions with the errant wheels). Another “exaggerated risk” discussed by Jones’s authors is the connection between secondhand smoking and cancer. Indeed, the spindoctoring goes so far as taking a judge’s decision to rescind the Environmental Protection Agency’s rule that acknowledged secondhand smoke as a carcinogen— a legalistic decision based on procedural matters— as “evidence” that the claim is scientifically unfounded.

While commenting on another book, written by authors Robert Lichter (president of the think tank Center for Media and Public Affairs and a paid consultant for Fox News) and Stanley Rothman (director of yet another think tank, the Center for the Study of Social and Political Change), Gildiner comments that one would look in vain for nuanced discussions about what should influence public policy. Rather, “what is to be found is a rhetorical, agenda-narrowing usage of scientific language and methods.”18 For example, Lichter and Rothman comment with an authoritative tone on the link between cancer and air and water pollutants, despite the fact that neither one is a scientist and that their sources were almost 20 years out of date. Science progresses; ideologies tend to linger unchanged (and often unquestioned).

One doesn’t really need to read technical articles about think tanks to get a good idea of what many (again, not all) of them are about. Take a look at the Web site of, for example, the Cato Institute (cato.org) and examine their timeline of actions and publications; it speaks for itself. In 1992 they published Sound and Fury: The Science and Politics of Global Warming, in which they state that “there is neither theoretical nor empirical evidence for a catastrophic greenhouse effect and thus no case for what Vice President Al Gore calls a ‘wrenching transformation’ of the American economy.” The following year, they produced Eco-Scam: The False Prophets of Ecological Apocalypse and Apocalypse Not: Science, Economics, and Environmentalism. Jump to 2000 and you will find The Satanic Gases: Clearing the Air about Global Warming. Is there a common thread here?

Or visit the even more obviously slanted site of the Competitive Enterprise Institute, which the Wall Street Journal named (without a trace of irony) “the best environmental think tank in the country.” One of their “scholars,” Robert J. Smith, proudly proposed the rather questionable concept of “free-market environmentalism,” and accordingly CEI was among the first organizations to criticize, back in 1990, the Clean Air Act amendments because they would “impose a new regulatory burden that would lead to higher energy prices” (perhaps, but would they make our air cleaner and our quality of life better?). There is more: CEI in 1992 “advised” the Food and Drug Administration to approve recombinant bovine somatotropin, which is a bioengineered growth hormone. Now surely such a recommendation would be accompanied by the further suggestion of labeling the resulting products so that consumer choice—that ultimate driver of market forces— could be openly exercised? Think again: the CEI argued that mandatory labeling of dairy products is “inappropriate” because it violates the First Amendment (which includes the right to free speech—of the cows?).

In 1996 the CEI folks outdid themselves, launching their Communications Project “with the aim of showing how ‘values-based’ communications strategies can help claim the moral high-ground for our side, by making the case that capitalism is not only efficient, but also fair and moral.”19 If this isn’t a frank admission that the CEI isn’t at all in the business of research but squarely in that of advocacy, it’s hard to imagine what is. Moreover, in 1999 CEI published a monograph arguing that the dumping (not their term) of trash in low-income rural communities in Virginia is actually good for those communities’ economies. One wonders how many fellows of the Competitive Enterprise Institute live in such communities. As recently as 2001 CEI helped persuade the Bush administration (which surely did not need much convincing on this issue) not to regulate carbon dioxide as a pollutant, despite the fact that the gas is universally recognized by scientists as the major contributor to the greenhouse effect. In 2002, CEI won a lawsuit against the FDA in federal court, invalidating the 1998 Pediatric Rule requiring drug companies to test some drugs on children, instead of automatically approving them for use on children if they had passed tests on adults only. To CEI’s evident chagrin, Congress wrote the Pediatric Rule into law.

In this age of global economies, the actions of think tanks of this sort go well beyond national boundaries: in 2003 a CEI fellow sent a letter to the Philippine president, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, advising her government to “disregard environmental alarmists and to continue allowing Filipino farmers to grow bioengineered corn.” Arroyo followed the suggestion, with apparently no input from her electorate and with predictable financial gains by the bioengineering firms that support CEI’s operations.

Back on national turf, in 2004 CEI exploited the usually high-quality television program Bullshit! with Penn and Teller, normally devoted to debunking the paranormal. The target? Mandatory recycling programs. In the same year, CEI associates argued that living on a McDonald’s diet is good for your cholesterol and that there really is no reason to panic if one finds high levels of lead in one’s water supply (as recently happened in Washington DC).

In 2005 the Competitive Enterprise Institute pushed for opening the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil and gas exploration, which could cause a major environmental disaster with likely little impact on the economics of oil supply, a discussion that once again took front stage during the 2008 American presidential elections. In the same year, CEI filed a challenge to the constitutionality of the 1998 multistate tobacco settlement, while the following year they patted the back of the EPA for allowing human volunteers to be used in studies on the effects of pesticides. Finally, again in a spectacular admission that this think tank is simply not interested in serious research and scholarship, the CEI defended the right of op-ed columnists to be paid by interested parties for the spin they give to their pieces: “An opinion piece—whether an individual op-ed or a column—exists to promote a point of view by argument. It does not seek to establish a fact, but to win people over to a particular viewpoint or opinion.” Indeed, but the reader usually assumes—wrongly, as it turns out—that it is the author’s opinion that one is reading, not that of a government agency or of a private corporation that surreptitiously paid for what superficially looks to the reader like an independent assessment. Caveat emptor!

While there is clear and rather disturbing evidence of an increasing shift from research to advocacy in the sociopolitical phenomenon of think-tankery, how much influence do think tanks really have, and how do they exercise it? Abelson and other researchers have repeatedly pointed out that it is difficult to measure such an elusive property as political and social influence. Attempts have been made to compare one think tank to another based on quantifiable parameters such as the number of press releases they put out that are picked up by major news outlets; the number of media appearances, especially on television, of the think tank’s fellows; and even the number of cabinet-level positions filled by people associated with a given think tank. Of course this scratches only the surface, because political influence can go undetected when it manifests itself as indirectly shaping the views and policies of representatives and senators at both the state and federal levels. When social commentators such as Rush Limbaugh or Bill O’Reilly relate “facts” that they gleaned from thinktank press releases, millions of listeners or viewers will not know or remember the source, only the facts, which may or may not be true. How does one measure that type of think-tank influence?

Obviously, much more research on and critical evaluation of the entire think-tankery phenomenon is needed; meanwhile, the public needs to be wary of the opinions proffered by allegedly unbiased “experts” whose affiliation to think tanks is barely acknowledged by media outlets.

We have analyzed jointly the alleged decline of public intellectualism and the rise of think tanks not because the two are necessarily directly related (though to some extent they may be), but because they both affect the teaching and understanding of science in the public arena, and they both are at the very least symptoms of the kind of transformation of modern society that has had commentators from Postman to Chomsky worried for a long time. Scientists and people genuinely interested in science should be worried too.![]()

References

- In Etzioni A. and A. Bowditch, eds. 2006. Public Intellectuals: an Endangered Species? New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 3.

- Car ter, David. 2001. “Public Intellectuals, Book Culture and Civil Society.” Australian Humanities Review, December.

- Chomsky, Noam. 1963. “The Responsibility of Intellectuals.” New York Review of Books, 23 February.

- Ibid.

- Etzioni and Bowditch, Public Intellectuals, 12.

- Posner, Richard. 2003. Public Intellectuals: A Study in Decline. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Etzioni and Bowditch, Public Intellectuals, 12.

- Dawkins, Richard. 1998. Unweaving the Rainbow: Science, Delusion, and the Appetite for Wonder. New York: Mariner Books.

- Furedi, Frank. 2004. Where Have All the Intellectuals Gone? New York: Continuum, 2.

- Stone, D. 2004. “Think Tanks, Policy Advice and Governance,” in Think Tank Traditions: Policy Research and the Politics of Ideas, ed. D. Stone and A. Denham. Machester University Press.

- Abelson, Donald. 2004. “The Business of Ideas: The Think Tank Industry in the USA,” in Think Tank Traditions, 215–29.

- Abelson, “Business of Ideas,” 220.

- Hudson, Leila. 2005. “The New Ivory Towers: Think Tanks, Strategic Studies and ‘Counterrealism’.” Middle East Policy, Winter.

- Osborne, Thomas. 2004. “On Mediators: Intellectuals and the Ideas Trade in the Knowledge Society.” Economy and Society, 4 November.

- Gildiner, Alina. 2004. “Politics Dressed as Science: Two Think Tanks on Environmental Regulation and Health.” Journal of Health, Politics, and Law, April.

- Ibid., 317.

- “About CEI,” at cei.org.

About the Author

MASSIMO PIGLIUCCI is a Professor of Philosophy at the City University of New York and a regular columnist for Skeptical Inquirer and Philosophy Now. In the areas of outreach and critical thinking, Pigliucci has published in Skeptical Inquirer, Philosophy Now, and The Philosopher’s Magazine, among others. He has published over a hundred technical papers and several books. He pens the Rationally Speaking blog, co-hosts the Rationally Speaking podcast, and has authored the popular science book Denying Evolution: Creationism, Scientism and the Nature of Science. His forthcoming book is The Intelligent Person’s Guide to the Meaning of Life (BasicBooks). Check out his author page on Amazon to see his other books.

Skeptical perspectives on intellectuals, human nature, and reason…

-

Who is Science Writing For?

Who is Science Writing For?

by Margaret Wertheim

-

The Blank Slate

The Blank Slate

by Dr. Steven Pinker

-

Inevitable Illusions

Inevitable Illusions

by Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini