In this week’s eSkeptic:

The Latest Episode of Mr. Deity: Mr. Deity and the Bang

WATCH THIS EPISODE | DONATE | NEWSLETTER | FACEBOOK | MrDeity.com

Upcoming Lecture: Margaret Wertheim

Physics on the Fringe: Smoke Rings, Circlons,

and Alternative Theories of Everything

Sunday, December 11, 2011 at 2 pm

Baxter Lecture Hall

FOR THE PAST 15 YEARS acclaimed science writer Margaret Wertheim has been collecting the works of “outsider physicists,” many without formal training and all convinced they have found true alternative theories of the universe. Jim Carter, the Einstein of outsiders, has developed his own complete theory of matter and energy and gravity that he demonstrates by experiments in his backyard—with garbage cans and a disco fog machine, he makes smoke rings to test his ideas about atoms. Captivated by the imaginative power of his theories and his resolutely DIY attitude, Wertheim has been following Carter’s progress for the past decade. Through a profoundly human profile of Carter, Wertheim’s exploration of the bizarre world of fringe physics challenges our conception of what science is, how it works, and who it is for.

Tickets are first come, first served at the door. Seating is limited. $8 for Skeptics Society members and the JPL/Caltech community, $10 for nonmembers. Your admission fee is a donation that pays for our lecture expenses.

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

Is America a Christian Nation?

Readers Respond To Chuck Colson

In a recent Los Angeles Times Op-Ed about Congress reaffirming the US national motto “In God We Trust,” Michael Shermer argued that trust does not come from God but from very specific social, political, and economic institutions. Chuck Colson argued that “God Has a Lot to Do With It.” In this week’s Skepticblog, readers respond to Colson.

MonsterTalk meets Skeptiko: The Psychic Detective Finale

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 170

In September of 2008, Ben Radford appeared as a guest on the podcast Skeptiko, hosted by Alex Tsakiris. During that interview, he agreed to take up Alex’s challenge to investigate the best case of the efficacy of psychic detectives. What followed was months of research, numerous interviews and a follow-up which ended in acrimony. Now, three years after the initial challenge, Skepticality presents a discussion between the hosts of MonsterTalk (Blake Smith, Ben Radford and Karen Stollznow) and Alex Tsakiris about Skeptiko, the interface of skeptics and believers, and the matter of whether or not Ben’s investigation disproved the psychic’s claims.

Interview with Joseph Lazio

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 171

In this episode of Skepticality, Derek speaks with Joseph Lazio, project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory for the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) telescope. Learn about what this next-generation radio telescope will be searching for and discover how it will address some of the fundamental questions in astrophysics, physics, and even astrobiology.

About this week’s eSkeptic

In this week’s eSkeptic, Michael Shermer reviews Lisa Randall’s Knocking on Heaven’s Door: How Physics and Scientific Thinking Illuminate the Universe and the Modern World (Ecco, 2011), a book in which Randall attempts “the herculean task of explaining to us uninitiated the daunting science of theoretical particle physics.” This review was originally published in the November 2011 issue of Science magazine.

As Far As Her Eyes Can See

book review by Michael Shermer

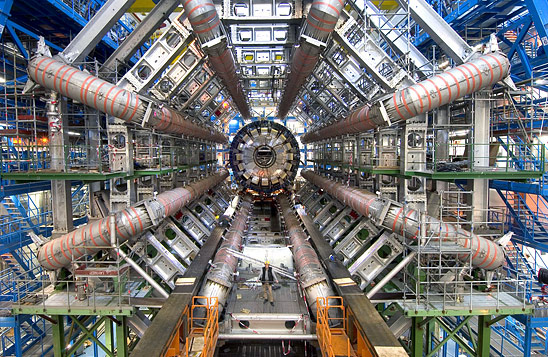

Lisa Randall has been justly appraised by Time magazine as one of the “100 most influential people in the world” for her work in theoretical particle physics. From her position at Harvard University, she often travels: to the European Laboratory for Particle Physics, CERN, in Switzerland, where her theories are being put to the test in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC); to speaking engagements with professional and public audiences about her work in particular and the awe and wonder of science in general; and to rock formations where her chalked fingers can find ways to defy gravity. On the side, she writes popular books, such as her acclaimed Warped Passages1.

In Knocking on Heaven’s Door, Randall picks up the story from where she left off when the LHC was years away from first collision, expanding her horizon from, as she poetically puts it, “what’s so small to you is so large to me” to “what’s so large to you is so small to me.” In other words, the book ranges from the smallest known particles to the entire bubble universe, from 10−35 meters (the Planck length, where quantum gravity rules) to 1027 meters (the entire visible universe, 100 billion light-years across, where dark matter and dark energy dominate), a stunning 62 orders of magnitude. (Randall correctly notes the age of the universe at 13.75 billion years, clarifying her apparently paradoxical figure of 100 billion light-years thusly: “The reason the universe as a whole is bigger than the distance a signal could have traveled given its age is that space itself has expanded.” She unpacks that sentence in the book.)

At the time of this writing, eBooks occupy about 20 percent of sales space; that is, one out of every five books sold has no cover or binding save the faux effects offered digitally by the various eBook readers. Of late, however, a tiny and growing sliver of the pie is being carved out by audio books (primarily through Audible.com and iTunes), most unabridged and read by professional actors and readers. These provide a welcome alternative to those of us yoked to our iPods and MP3 players inside cars and gyms or on bicycles and hiking trails. Since fumbling around with cassette tapes and Sony Walkmans in the early 1980s, I have consumed on the order of 500- plus nonfiction audio books, so a measure of an author’s skill to communicate complex material clear enough to penetrate a multitasking cortex has become a mark of quality (or lack thereof). Many are called. Few are chosen. Randall’s explanatory prose places her among the elect. She is not alone, but she is rare among the many who have attempted the herculean task of explaining to us uninitiated the daunting science of theoretical particle physics. She devotes most of Knocking on Heaven’s Door to covering this science, along the way offering fascinating accounts of how the LHC was built, how the experiments are run, and, most notably, the engineering prestidigitation involved in teasing out nature’s secrets via energies never before witnessed on Earth.

The book’s subtitle hints that it may be yet another long and tiresome treatise on science and religion, with either convoluted (and ultimately failed) attempts at conciliation or pugnacious left hooks and fast jabs at the faithful. Neither are Randall’s modus operandi. She states her case succinctly and moves on. Stephen Jay Gould’s “nonoverlapping magisteria,” for example, would work if only religions would stick to doing what they do best (providing aid and comfort to the poor and needy). However, conflicts arise the moment “religions attempt to address the external reality of the universe.” When they do, Randall notes, “[t]his leaves religious views open to falsification. When science encroaches on domains of knowledge that religion attempts to explain, disagreements are bound to arise.” As science expands its realm, the magisteria are becoming ever more overlapping. The deeper problem, however, is that if divine providence were on the offing, “it is inconceivable from a scientific perspective that God could continue to intervene without introducing some material trace of his actions.” In other words, if God did act in the world scientists would want to know how he did it. “Did He apply a force or transfer energy?” Randall asks rhetorically. “Is God manipulating electrical processes in our brains? … On a larger level, if God gives purpose to the universe, how does He apply His will?” Inquiring minds want to know. Religion has no answer. I know because I have asked many times.

Another myth Randall thankfully busts is the notion of truth and beauty in science. What can a “beautiful truth” in science possibly mean? Take a look at a page of equations and formulas from a recent theoretical physics paper. Mind-boggling to the untrained maybe, complicated and detailed undoubtedly, surprising or inspiring occasionally, but beautiful? “Beauty is often agreed on only a posteriori,” Randall explains, although she adds the proviso “even though aesthetic criteria for science might be poorly defined, they are nonetheless useful and omnipresent. They help guide our research, even if they provide no guarantee of success or truth.” Considering weak interactions, which violate parity symmetry, she remarks, “The breaking of such a fundamental symmetry as left-right equivalence seems innately disturbing and unattractive. Yet this very asymmetry is what is responsible for the range of masses we see in the world, which is in turn necessary for structure and life.”

Knocking on Heaven’s Door came out before the faster-than-light neutrino experiment was announced2 and paraded through the press as an ostensible refutation of Einstein, implying in some circles that science is nothing more than one failed theory after another. Why thence should we believe anything scientists say about evolution, global warming, or vaccines? Randall ends her book with a thoughtful discussion of how science really works to resolve anomalies unexplained by the prevailing paradigm. Einstein did not overturn Newton; he just expanded on the physical properties of the universe at high speed and large scale. If you want to get a spacecraft to the moon, Newton will take you there. As flawed as it sometimes can be, science is still the most reliable tool ever devised for understanding the world. Few have captured this essence better than Randall in Knocking on Heaven’s Door.

References & Notes

- L. Randall, Warped Passages: Unraveling the Universe’s Hidden Dimensions (Allen Lane, London, 2005); reviewed in (3).

- http://arxiv.org/abs/1109.4897.

- J. D. Wells, Science 311, 40 (2006).

Suggested reading on cosmology and physics…

-

Warped Passages: Unraveling the Mysteries

Warped Passages: Unraveling the Mysteries

of Hidden Dimensions

by Dr. Lisa Randall

-

Physics of the Impossible

Physics of the Impossible

by Dr. Michio Kaku