In this week’s eSkeptic:

Interview with Scott Hannahs

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 172

This week’s guest on Skepticality is Dr. Scott Hannahs, the Director of DC Field Instrumentation and Facilities National High Magnetic Field Laboratory. Find out a bit about what it is like to work with the worlds most powerful magnet, what types of experiments require such a powerful bit of scientific equipment, and what discoveries and research come out of the science of magnetic fields.

About this week’s eSkeptic

In this week’s eSkeptic, Michael Shermer reviews Margaret Wertheim’s Physics on the Fringe: Smoke Rings, Circlons, and Alternative Theories of Everything. This book review first appeared in the Wall Street Journal on December 10, 2011.

On the Margins of Science

book review by Michael Shermer

As the editor of Skeptic magazine and a monthly columnist for Scientific American I am often sent self-published books and manuscripts that I store in a box labeled “Theories of Everything.” These are mostly attempts at constructing all-encompassing explanatory theories claiming to have disproven Newton, Einstein, and Hawking, and that in 10 or 100 pages sans equations or references the secrets of the cosmos are revealed. One is entitled “Introduction to the Unified Field Theory,” in which the author boasts, “I have discovered the previously unknown invisible particle that fully explains light and all forms of energy. I call it the froton particle. Einstein didn’t know about the froton particle—but you will.” A manuscript entitled Infinite Dynamics goes “beyond Einstein,” and represents “an historic, classical, artistic, scientific, philosophical paradigm shift.” Another called Photonics promises “Einstein’s unified-field theory now complete, all forces finally unified,” and as a bonus, “fundamental cause of gravity found.” Another proclaimed that his “is the first consistent theory of anti-gravity in the history of mankind,” revealing the secrets to “time warp interstellar travel, wormhole engineering and Dipole Antigravity Drive, gravitational free energy, and alien visitation.”

I admit that I have not given these ideas much credence, but what if one of them turns out to be right, or at least has something of value to offer to society? For the past 15 years the acclaimed science writer Margaret Wertheim (Pythagoras’ Trousers, The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace) has been collecting the works of such hermit scientists, or what she calls “outsider physicists,” and with the patience of Job has undertaken the scientifically thankless task of carefully reading as many “theories of everything” as she could get her hands on to give them a fair hearing, and more. In Physics on the Fringe Wertheim presents these ideas with an eye toward challenging our preconceptions of what science is, how it works, and who it is for. The book is so well-written, entertaining, and enlightening that I read it straight through in one sunny day at the beach. Only later did I realize that Wertheim has also taken on one of the knottiest conundrums in the philosophy of science called the demarcation problem, or finding criteria to define the boundary between science and pseudoscience. It’s not as easy as it sounds.

As a professional debunker I feel like I know bunk when I see it, and Wertheim has well captured the genre: “In all likelihood there will be an abundant use of CAPITAL LETTERS and exclamation points!!! Important sections will be underlined or bolded, or circled, for emphasis. Frequently the author will have seen fit to ease the professor’s path toward understanding by writing helpful comments in the margins of the paper or by highlighting critical passages with brightly colored felt-tip pens… The text itself will almost certainly herald its revolutionary nature in its opening paragraphs, claiming to reinvent if not the whole of physics…then at least substantial parts of it. At a minimum, the author will be proposing something radically new and often as not will have harsh words for the twin pillars of twentieth-century physics—relativity and quantum theory.”

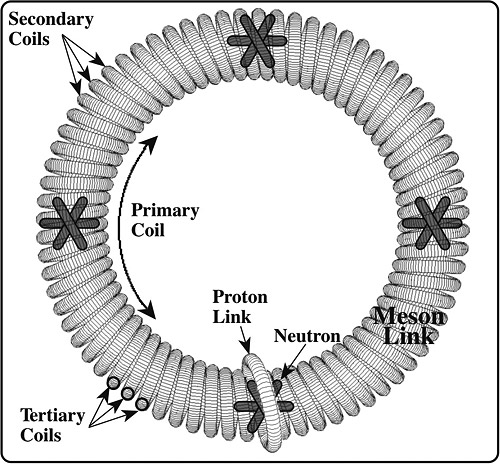

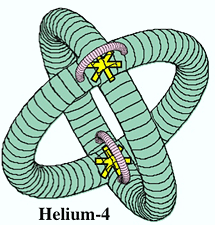

Outward appearances aside, Wertheim has convinced me that I may be too hasty in dismissing outsiders a priori, most notably the central character of her story—a man she calls the Einstein of outsiders, Jim Carter, who has developed his own complete theory of matter, energy, and gravity that he demonstrates by experiments in his backyard with DIY contraptions involving garbage cans and a disco fog machine, from which he makes smoke rings to test his ideas about atoms, which he believes are constructed of “circlons,” or “Hollow, ring-shaped mechanical particles that are held together within the nucleus by their physical shapes,” as seen in Figure 1 (below), and in representing the helium atom in Figure 2, the 2nd simplest element made up of two circlons. His circlon theory allows him to tie together both quantum mechanics and the special and general theories of relativity, and his explanation for gravity is unorthodox to say the least: “if the earth’s surface is constantly moving away from its center, we must conclude that the earth, as well as all other matter, is constantly expanding in size; and it is this expansion that causes the phenomenon we know as gravity.”

Figure 1: The Circlon (courtesy of Jim Carter). See also Jim Carter’s Circlon Model of Nulcear Structure (PDF, copyright 1993).

Figure 2: The Helium Atom Circlon (courtesy of Jim Carter). See the Physics on the Fringe website for more information about Jim Carter’s physics, including links to photos and videos.

Before you laugh (especially at the neologism), as I initially did, Wertheim points out that string theory—touted regularly on science documentaries as the ultimate theory of everything endorsed by prominent scientists the world over—has not a shred of empirical evidence in its favor and is, in reality, nothing more than a mathematically elegant construct. If Carter’s circlon theory is pseudoscience, why isn’t string theory? For example, Wertheim describes a meeting she attended of the Natural Philosophy Alliance, a group devoted to challenging mainstream physics. The eccentric event played host to no fewer than 121 fringe theories of the universe, “each claiming to present a key to Ultimate Reality,” Wertheim recalled. It reminded her of the book The Three Christs of Ypsilanti, the story of three schizophrenic patients in a room together at the Ypsilanti State Hospital in Michigan, all of whom thought they were Jesus (each of whom ultimatey decided that the other two were imposters). At this conference, she recounted, “Everybody had the Answer. Everybody was the One.” There was bewilderment amongst the participants: “How exactly is a person supposed to respond to someone else’s harebrained theory when each person has his or her own Solution?”

Wertheim goes on to contrast the NPA gathering with a meeting of string theorists she attended in which such scientific supernovae as Stephen Hawking, Lisa Randall and Brian Greene spoke seriously about 11-dimensional universes, multiverses, parallel universes, and even the possibility of there being at least 10500 variants of string cosmologies, including one proffered by Stanford’s Leonard Susskind in which every universe that can exist does exist in a superuniversal space. When Wertheim asked the organizer of the insiders conference his opinion of one particularly dazzling talk, he enthused “Utterly splendid. Of course there’s not a shred of evidence for anything the fellow said.” As Wertheim recalled, “Whoever I talked with assured me that everybody else’s theories were unsupported by evidence and based entirely on arbitrary assumptions. None of this was driven by physical discoveries.”

What, then, are we to do with outsiders’ contributions to science? When they are contrasted with equally baseless theories, says Wertheim, listen to them. “In the final analysis Jim’s circlon-shaped particles may also be seen as manifestations of a string theory, for his subatomic springs are also coils of some minutely thin, ‘stuff.’ Jim came to the string concept more than thirty years ago, and the fact that this idea is now being embraced by the mainstream suggests to him that his other ideas will one day be vindicated too.”

Will they? Maybe. Or perhaps both circlon theory and string theory will go the way of phlogiston and phrenology on the scrapheap of science history. Time and observation will tell, for as the great astrophysicist who confirmed Einstein’s theory of relativity, Arthur Stanley Eddington, noted: “For the truth of the conclusions of science, observation is the supreme court of appeal.” In the meantime, let’s not dismiss outsiders before giving them their day in court. Margaret Wertheim has done just that in this splendid book.

May we suggest these related items…

-

Heaven and the Internet

Heaven and the Internet

by Margaret Wertheim

-

Who is Science Writing For?

Who is Science Writing For?

by Margaret Wertheim

-

Skeptic magazine volume 10, no. 2

Skeptic magazine volume 10, no. 2

includes a special report on Stephen Wolfram by David Naiditch -

In 2002, the legendary Stephen Wolfram stepped into the public eye promising to revolutionize the way we do science. For hundreds of years, scientists have successfully used mathematical equations that show how various entities are related. Wolfram believes that simple computational rules (rather than equations) could better capture the complexities of nature. According to Wolfram, the discovery that simple rules can generate complexity—a discovery he attributes primarily to himself—is “one of the more important single discoveries in the whole history of theoretical science.”

READ the Table of Contents and order the back issue.