In this week’s eSkeptic:

- The Amazing Meeting 2013: July 11–14, South Point Casino, Las Vegas

- Follow Daniel Loxton: That Time Houdini Threatened to Shoot All the Psychics

- Skepticality: Spot The Bull

- New Episode: Mr. Deity and The Chaplain

- Feature Article: Non-Designer Design

- Our Next Lecture: Dr. Adam Grant on a Revolutionary Approach to Success

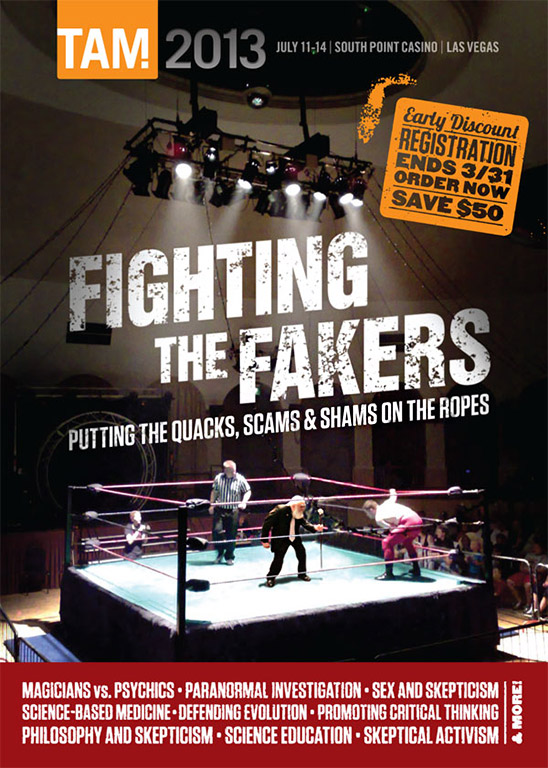

Join Us For The Amazing Meeting 2013

South Point Casino, Las Vegas

July 11–14, 2013

THIS ANNUAL GATHERING of critical thinkers is an unparalleled opportunity to make like-minded friends, enjoy some of the brightest minds on issues important to us, and leave with tools for sharing a helpful and skeptical message to those who might be hurt by charlatans and unfounded belief.

A major motivation for going to TAM is that skeptics care deeply about people and they know that when people believe in nonsense, they often get hurt. And at TAM 2013 we will explore ways to fight back. This is central to the missions of the James Randi Educational Foundation and The Skeptics Society — James Randi and Michael Shermer have both been fighting the fakers for decades.

Don’t miss out on this amazing event! Tickets are selling fast and registration prices will increase after March 31.

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

That Time Houdini Threatened to Shoot All the Psychics

Daniel Loxton considers the case of an ethically questionable 1896 skeptical activism hoax described by skeptic Joseph Rinn.

Spot The Bull

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 204

This week on Skepticality, Derek has a discussion with Loren Collins, the author of Bullspotting: Finding Facts in the Age of Misinformation, a guidebook for people to distinguish between real conspiracies and conspiracy theories, and real science from pseudoscience. Collins’ book provides a way to use the tools of critical thinking to spot real evidence from information which has been manipulated to create false impressions of the truth.

Get the Skepticality App

Get the Skepticality App — the Official Podcast App of Skeptic Magazine and the Skeptics Society, so you can enjoy your science fix and engaging interviews on the go! Available for Android, iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch. Skepticality was the 2007 Parsec Award winner for Best “Speculative Fiction News” Podcast.

The Latest Episode of Mr. Deity: Mr. Deity and The Chaplain

WATCH THIS EPISODE | DONATE | NEWSLETTER | FACEBOOK | MrDeity.com

About this week’s eSkeptic

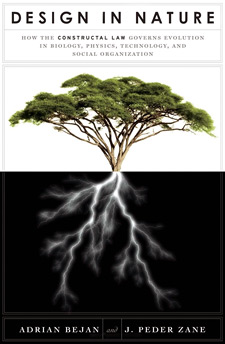

In this week’s eSkeptic, Chad Jones reviews Design in Nature: How the Constructal Law Governs Evolution in Biology, Physics, Technology, and Social Organization, by Dr. Adrian Bejan and J. Peder Zane (Doubleday, 2012, ISBN 9780385534611). The reviewer questions whether the authors’ notion of “the contructal law” adds anything to Darwin’s theory of evolution via natural selection.

Chad Jones was born in California, studied Engineering Technology at Old Dominion University and is a veteran of the armed forces. He currently resides in South Carolina with his wife and daughter.

Non-Designer Design

a book review by Chad Jones

Upon reading the title Design in Nature: How the Constructal Law Governs Evolution in Biology, Physics, Technology, and Social Organization in an engineering magazine, I was curious as to how creationist literature found its way into a respected engineering publication. I was prepared for poorly reasoned arguments, but instead I found something insightful.

Duke University engineer Dr. Adrian Bejan believes he has discovered a fundamental law of physics that unites such seemingly disparate fields as biology and engineering with a simple idea: systems achieve better design as part of a natural process. Quelling any fears of creationist type arguments, Dr. Bejan specifically states that his position does not posit the existence of a “designer” and that design occurs naturally as a principle of physics; this principle he calls “the constructal law”.

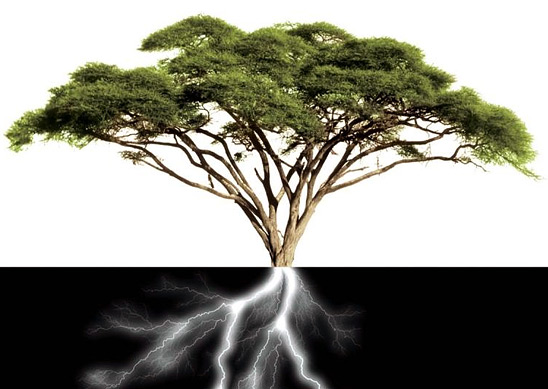

The constructal law encompasses both “animate” and “inanimate” systems by modeling both as “flow systems.” A flow system is defined as “one or more streams that originate from points and must find easier access to other points.” Think of lightning flashes in their zigzagging patterns that resemble branching trees or waterway tributaries. The material that flows can be a physical media, such as water in a riverbed, information in a business, or heat in a semi conductor. The constructal law proposes that everything that moves is a flow system, from ants and animal herds to rivers and electric currents, and given freedom flow systems evolve over time in order to flow more easily.

Dr. Bejan also describes how this universal tendency accounts for the patterns that we call design in nature, and illuminates the fact that all flow systems are connected to and shaped by other systems in a “global tapestry” of flow. Where there is flow, there is change: “The constructal law dictates that flow systems should evolve over time, acquiring better and better configurations to provide more access for the currents that flow through them.” (p. 5). The author also makes the argument that everything that moves is part of a flow system, and that anything that changes its configuration to provide easier access to the currents that flow through it, is alive.

The author proposes that even longstanding mysteries of mathematics, when viewed in light of this law have simple explanations. The “golden rectangle”, sometimes considered to be aesthetically pleasing, is explained to be a manifestation of the constructal law where the human field of vision and the ratio of horizontal to vertical sweep approximate the “golden rectangle.”

Here is where a skeptical reader may reasonably wonder how much finding the constructal law everywhere is nothing more than the confirmation bias at work, where one finds confirming evidence for what one believes and ignores the disconfirming evidence. Dr. Mario Livio, author of The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World’s Most Astonishing Number, specifically dismisses the idea that the golden rectangle approximates the visual field and points out that, where it is even agreed that the “golden rectangle” is preferred, ratios ranging from 1.5 to 1.9 were found pleasing. “In an experiment conducted in 1966 by H.R. Schiffman of Rutgers University, subjects were asked to ‘draw the most aesthetically pleasing rectangle’ that they could on a sheet of paper… While Schiffman found an overwhelming preference for a horizontal orientation, consistent with the shape of the visual field, the average ratio of length to width was about 1.9—far from both the Golden Ratio and the visual field’s ‘average rectangle’” (p. 181).

A number of points in Design in Nature appear be true by definition. Dr. Bejan argues that “treelike” structures are best for flow between an area and a point and vice versa; but what other possibility is there for discrete flows? By what other definition is something “treelike”? Systems for moving items from point to point are not treelike, if they were treelike, they would connect areas to points by definition.

One major issue (scientifically speaking) that is not addressed with the constructal law is how to apply it objectively. Dr. Bejan describes flow as “the movement of one entity (in the channel) relative to another (the background)” but never explains how to decide which flow should be used to model a flow system. When modeling a complex system, such as animal life, the number of potential “flows” seem enormous; is it wrong to model animals as flow systems that turn food into waste? Is it wrong to model animals as flow systems for passing their genes to the next generation? Why does the author choose to model animals as flow systems that “move mass better and better (to cover more distance per unit of useful energy) across the landscape”? (p. 4). If there are answers to these questions, they do not seem to be contained within this text.

There are also a number of caveats in the book that would dismiss any observation that does not fit predictions of the constructal law, seemingly out of hand: “Of course, there will be bumps and mistakes: Every trial involves error. But in broad terms, tomorrow’s system should flow better than today’s” (p. 9).

Design in Nature attempts to address numerous far reaching topics, and to present a plausible explanation for how similarities can exist in all branching structures. Design In Nature groups phenomena by superficial similarities and goes against Occam’s razor by adding complication where it is not necessary (an example being the eddies created when pouring a beer into a glass as a consequence of the constructal law, instead of the incompressibility of fluids and fluid dynamics). The author also challenges evolution by positing that while animals may compete in accordance with Darwinian natural selection on some levels, on a larger scale “They are not competing against each other but working together” (p. 146).

The writing is accessible, but sometimes suffers from problems with word choice and style, likely due to the lack of a unique and accurate vocabulary necessary when describing a new topic. This issue is acknowledged in the book, and as new fields evolve the language used to describe them takes time to catch up. Much of the vocabulary used also has connotations and stigmas that are difficult to overcome. “Design may be the foundation of the built world, but it is anathema when the conversation turns to nature. Its six letters have become the four-letter word of biology and physics” (p. 29). That’s hyperbole. Biologists speak of natural design in nature without qualm, as in functional design such as eyes designed to see and wings designed to fly. Darwin’s natural selection gives us a theory of natural design via functional adaptations. It’s not clear to me what the constructal law adds to this concept of design already in use.

All told, Design in Nature is interesting and engaging and easy to read. It challenges perhaps every scientific belief currently held and encourages a new look at long standing explanations; and few things are more skeptical than that. ![]()

Our Next Lecture at Caltech:

DR. ADAM GRANT

Give and Take:

A Revolutionary Approach

to Success

with Dr. Adam Grant

Sunday, April 28, 2013 at 2 pm

IN THIS LECTURE, based on his book on the psychology of human interactions, organizational psychologist (and the youngest tenured professor at the Wharton Business School) argues that as much as hard work, talent and luck, the way we choose to interact with other people defines our success or failure. Give and Take demolishes the “me-first” worldview and shows that the best way to get to the top is to focus not on your solo journey but on bringing others with you. Grant reveals how one of America’s best networkers developed his connections, why a creative genius behind one of the most popular shows in television history toiled for years in anonymity, how a basketball executive responsible for multiple draft busts turned things around, and how we could have anticipated Enron’s demise four years before the company collapsed—without ever looking at a single number.

Followed by…

- Odd Couples: Extraordinary Differences between the Sexes

in the Animal Kingdom

with Dr. Daphne J. Fairbairn

Sunday, May 19, 2013 at 2 pm

New Admission Policy and Prices

Please note there are important policy and pricing changes for this season of lectures at Caltech. Please review these changes now.