In this week’s eSkeptic:

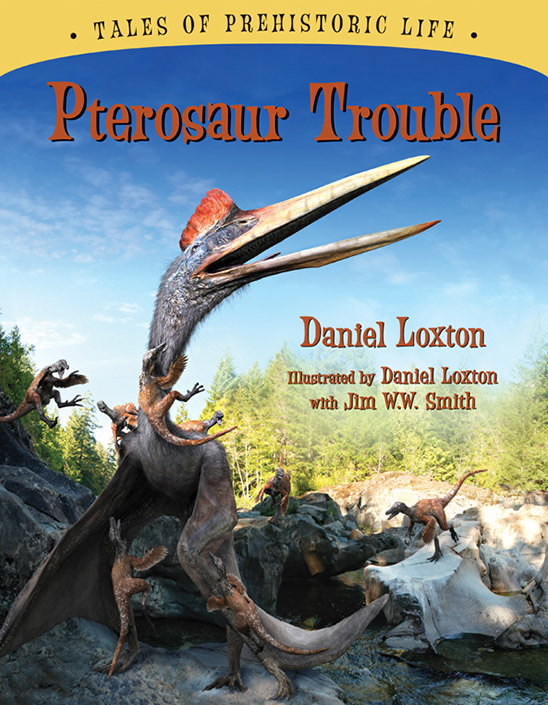

Pterosaur Trouble

a new book by Daniel Loxton,

now available at Shop Skeptic

In this science-informed followup to his Silver Birch-nominated Ankylosaur Attack, Daniel Loxton tells a dramatic paleofiction tale of perhaps the largest flying animal ever to exist—the mighty pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus. While stalking a riverside for breakfast, the giraffe-sized pterosaur finds himself on the menu for a pack of small but ravenous feathered Velociraptor-like dinosaurs called Saurornitholestes. Can the giant escape from his Lilliputian assailants?

Inspired by real-world fossil discoveries, this photorealistic adventure (Book 2 in the Kids Can Press series Tales of Prehistoric Life) will delight and astonish.

- Reading level: Ages 4 and up

- Hardcover: 32 pages

- Publisher: Kids Can Press

Praise for Pterosaur Trouble

Tense narration…exquisite detail…remarkably real.

Dino devotees…will devour this eye candy with relish.

DVD Price Reduction

Lectures at Caltech on DVD

now only $19.95 each!

We are pleased to announce a permanent price reduction on our DVDs of lectures at Caltech. Since 1992, the Skeptics Society has sponsored The Skeptics Society Distinguished Science Lecture Series at Caltech: a monthly lecture series at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, CA. Lectures are now available for purchase on DVD for $19.95 each (formerly $23.95). To get a taste of what our lectures are like, watch Sam Harris’ lecture on Free Will for free on YouTube.

Our Next Lecture at Caltech

DR. ADAM GRANT

Give and Take:

A Revolutionary Approach

to Success

with Dr. Adam Grant

Sunday, April 28, 2013 at 2 pm

IN THIS LECTURE, based on his book on the psychology of human interactions, organizational psychologist (and the youngest tenured professor at the Wharton Business School) argues that as much as hard work, talent and luck, the way we choose to interact with other people defines our success or failure. Give and Take demolishes the “me-first” worldview and shows that the best way to get to the top is to focus not on your solo journey but on bringing others with you. Grant reveals how one of America’s best networkers developed his connections, why a creative genius behind one of the most popular shows in television history toiled for years in anonymity, how a basketball executive responsible for multiple draft busts turned things around, and how we could have anticipated Enron’s demise four years before the company collapsed—without ever looking at a single number.

Followed by…

- Odd Couples: Extraordinary Differences between the Sexes

in the Animal Kingdom

with Dr. Daphne J. Fairbairn

Sunday, May 19, 2013 at 2 pm

NEW ON MICHAELSHERMER.COM

Proof of Hallucination: Did a neurosurgeon go to heaven?

In Michael Shermer’s April 2013 ‘Skeptic’ column for Scientific American, he argues that Eban Alexander, author of the book Proof of Heaven: A Neurosurgeon’s Journey into the Afterlife, was simply hallucinating during his near-death experience, and discusses a number of factors that produce such fantastical hallucinations that could convince a person that he or she has gone to heaven and returned.

About this week’s eSkeptic

In this week’s eSkeptic, L. Kirk Hagen reviews Human No More: Digital Subjectivities, Unhuman Subjects, and the End of Anthropology, edited by Neil Whitehead and Michael Wesch (University Press of Colorado, 2012, ISBN 978-1607321897).

Dr. L. Kirk Hagen, Ph.D., is a professor of humanities at the University of Houston-Downtown. He has been contributing articles to Skeptic since 2002, mostly on topics related to philosophy, language, education, and the social sciences.

Anthropology No More

a book review by L. Kirk Hagen

It has been more than a decade since anthropology endured its worst-ever humiliation following the publication of Patrick Tierney’s Darkness in Eldorado, which brought infamy to anthropology with its accusation that the iconic American anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon had committed genocide in Amazonia. Tierney, along with collaborators Terence Turner and Leslie Sponsel, falsely claimed that Chagnon had unleashed a deadly epidemic among the Yąnomamö by administering a contraindicated measles vaccine as part of some sinister experiment in eugenics. That was just the most outrageous of Tierney’s innumerable fabrications, which inexplicably slipped past the fact-checkers at W. W. Norton and New Yorker magazine. About a year ago, medical historian Alice Dreger published what may be the final word on the Darkness scandal, and the news was not good. Dreger argues persuasively that anthropology’s premier North American professional organization, the American Anthropological Association (AAA), had been complicit in the promulgation of Tierney’s calumnies. (See Alice Dreger, “Darkness’s Descent on the American Anthropological Association; A Cautionary Tale.” Human Nature 22 (2011): 225–246.)

Since then, as the editors of Human No More acknowledge, anthropology has been trying to reboot and move into terrain free of the ethical quicksand that comes with traditional Malinowskian ethnography. The discipline is now at “a critical juncture,” writes lead editor Whitehead, and failing to address its problems “has led others to question anthropology’s purpose” (220). Whitehead and co-editor Wesch propose to “stake out new anthropological fields and take us beyond the human” (219) by studying the “discursive panorama” of the unhuman, the subhuman, the nonhuman, and other marginalized or digitized beings (6). Part of this hazy objective is to establish an agenda that recognizes humans as “part of much larger systems that include relationships with animals, insects, microorganisms, spirits, and people who are not always considered human by others” (9). This is the End of Anthropology, as the book’s subtitle says; a double-entendre hinting at either anthropology’s grand new objective, or its coming demise. Unfortunately, it is not clear from Human No More which is the more likely outcome.

There is much to recommend this book. In Chapter 8 “Technology, Representation and the E-thropologist,” Alemán skillfully analyzes the “collision” between modern technology and traditional culture among the Waiwai of Guyana and Brazil. She reminds us that, on the one hand, exotic technologies often co-opt pre-industrial cultures long-term. On the other hand, to purposefully withhold from those cultures things like computers, shotguns, and yes, measles vaccines, is to consign them to the status of performers who, to their own detriment, fulfill some perverse fantasy of the well-to-do. “[W]e may not consider that they may actually want to be like us,” Alemán writes (149). Hoesterey gives another example of this persistent shame in Chapter 9, “The Adventures of Mark and Olly,” where he explains how the producers of the Travel Channel’s Living with the Mek invented a caricature of Papuan cultures in order to slake their viewers’ thirst for the bravado of “extreme tourists” confronting the “untouched savage” (162). In a somewhat similar vein, Wisniewski’s chapter “Invisible Cabaclos and the Vagabond Ethnographers” reflects on the tensions between ethnographer and the voices of informants, and how anthropologists often “agonize over how to represent those voices to others” (179). Wisniewski comes to accept his informants as collaborators. His chapter is a sincerely introspective work that should serve as a model for ethnographers.

The book’s most obvious shortcoming is that nothing resembling a coherent theoretical program ever emerges from its twelve chapters. Some chapters deal with digital phenomena like chatbots, social media, or Anonymous. Others are about marginalized subcultures or indigenous peoples of Amazonia (lead editor Whitehead, like Chagnon and Tierney, had an enduring interest in Amazonian cultures). Contributors and editors alike try to establish some commonality among these groups, but more often than not their efforts come off as one-dimensional and contrived. At times Human No More veers into the kind of sensationalism already apparent in its title. Elsewhere it barely rises above the mundane. In her analysis of e-mail, Ryan (Chapter 4) writes that “[t]he simple act of pressing ‘send’ is the fulfillment of the intention behind this particular communicative act, because seeing the message displayed on screen confirms that communication has occurred” (84). Yet as every e-mail user knows, that display only confirms a message has been sent. It is no guarantee of readership.

Bernius’s chapter “Manufacturing and Encountering ‘Human’ in the Age of Digital Reproduction” tells the story of an online encounter with “Az_Tiffany” in a chat room as Bernius tries to recruit webcam users for a study. He eventually discovers that he had been “pwn’d” by a bot. But as Bernius belatedly acknowledges, it ought to have been obvious that he was not talking directly to a human (57). The script behind Az_Tiffany’s responses is noticeably cruder than what the original bot ELIZA was capable of back in the 1960s. Nothing of theoretical import comes from this story, except that cyberspace is teaming with hustlers. A closer look at Hoesterey’s chapter is similarly disappointing. Yes, 21st Century Reality TV is heavily scripted, edited, and decontextualized. But we don’t need anthropologists to tell us that. A television will do just fine.

Nevertheless, it is Hoesterey who finally identifies the source of anthropology’s malaise. “The decolonization of anthropology,” he writes, “is not some mess cleaned up by the postmodernist turn and absolved with an apologetic gaze to anthropology’s past” (174). Indeed, it isn’t. In fact, it was the postmodernist turn that created anthropology’s mess in the first place.

Postmodernism was a fad invented largely by a coterie of French literati in the late 1960s. It subsequently degenerated into social ideology and found its way into other disciplines, notably philosophy, cultural studies, and, finally, anthropology. It was an ideology that privileged flourish over substance, sentiment over reason, and politics over principles. It had a long-standing love/hate relationship with science—quantitative studies are conspicuously absent from Human No More—and an equally stubborn hate/hate relationship with anything perceived to be of Western origin. Postmodernism reveled in sweeping pronouncements (e.g. “We are human no more”), so long as those pronouncements were couched in the pretentious postmodern idiom, whose vagueness served as a bulwark against refutation. When Whitehead writes that humans are part of larger “systems” (what does that mean so far?) that include “spirits,” is he seriously asserting that supernatural beings exist, or only that people believe in them? If it’s the former, then Whitehead is mistaken. If it’s the latter, he is making a claim no one would think of disputing. When Hoesterey and Allison inveigh against evolution (170, 232), are they really aligning themselves with religious zealots as the last remaining deniers of biology’s foundational principle? Or what else do they have in mind?

The most unsettling example of postmodern weasel-wording in Human No More comes in its conclusion, where Whitehead revisits anthropology’s uncertain future:

[T]he outcomes of failing to address [anthropology’s] epistemological and ontological problems are already with us and have proliferated, leading to some serious ethical and political issues in professional practices with, at times, lethal consequences. (Tierney 2002, Whitehead 2009a). (220)

“Tierney 2002” is a reference to Darkness in El Dorado, the slander that has permanently stained postmodern anthropology. But what “lethal consequences” does Whitehead have in mind? Is he hinting, yet again, that there just might be something to Tierney’s murder-by-measles fantasy? If yes, why not just say so, and if not, why write sentences like that? Whitehead was among the countless AAA associates who were guilty of praise by faint damnation in the Darkness scandal. In fact, in his paper “South America / Amazonia: The Forest of Marvels,” Whitehead makes it clear that he actually believed Patrick Tierney’s fiction. (See Chapter 7 in Peter Hulme and Tim Youngs (eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Travel Writing. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge Press, 2002, 122–138.) That debate has nonetheless been settled. By trying to resuscitate it a decade later, Whitehead only reinforces the view that postmodern anthropology is either unable or unwilling to shake off its troubled past.

The traces of the postmodern turn show up everywhere in Human No More. There are the obligatory homages to Derrida, Latour, Butler, and other gods of the postmodern pantheon, even when those gods have nothing relevant to say about the topic at hand. There is the compulsive use of scare quotes to qualify any word that might be construed as referring to some objectively real truth, as in “real”, “truth,” and, of course, “human” (pp. 2, 37, 52, respectively). There is sloganeering from the far-left postmodern economic agenda as well (in the Introduction, and in Chapters 6, 11 and 12), although lumping together the plight of middle-class devotees of World of Warcraft (Chapter 7) and the plight of homeless crack addicts of Sao Paolo (Chapter 11) is not a particularly progressive social view. For good measure, there is the occasional postmodern gimmick of bracketing of morphemes in paren(theses) for no particular reason (75, 89, 199).

Worst of all, Human Nor More is rife with examples of the pernicious postmodern addiction to sentences that don’t mean anything. Alemán adds nothing to her ethnography of the Waiwai when she concludes: “The somatic endurance requirements disappear only to be replaced by other requirements. In these subjective engagements, the field begins to shape-shift” (154). This is followed by puerile innuendo, yet another hallmark of the postmodern turn. Quoting Whitehead, Alemán writes that “such inadequate coverings as the fig leaf of scientific observation will now not be enough to hide the bulge of anthropological desire” (154).

This postmodern/posthuman fear of science ultimately prevents the contributors of Human No More from seeing something in plain sight. In Chapter 3, Bernius ruminates on artificial intelligence, and differences between human and machine cognition. Is there really a mystery here? Humans and computers do not think alike because they don’t have the same evolutionary history. Our brains are the product of millions of years of adaptation to environments that change slowly but inexorably. We share many cognitive and behavioral traits with other primates, and indeed with other mammals. But we have a much larger and more complex neocortex, and consequently more complex forms of personal and social interactions. Computers don’t live in that world; they don’t hunt, gossip, compete for reproductive rights, or suffer from remorse and jealousy. They can beat humans at chess and Jeopardy!, but they don’t high-five each other afterwards.

In this respect, computers are more analogous to Canis lupus familiaris and so many other species that we have modified to suit our needs. Some dogs excel at hunting; others at herding or guarding. Some computer apps excel at graphics manipulation; others at crunching numbers or mining data. Domestic animals and machines have neither destroyed Homo sapiens nor morphed it into an unrecognizable new species. At most, they have motivated a more expansive understanding of human nature. Ironically, the heirs to Chagnon’s sociobiology—Richard Dawkins, Steven Pinker, Sarah Hrdy and others—have far outpaced postmodern anthropologists in explaining what human nature is like.

The postmodern turn will turn 50 sometime this decade, depending on where one situates its origins. To put that into perspective, the 1960s are to the 2010s what the 1910s were to the 1960s. The definitive debunking of postmodern pop-thought—Sokal and Bricmont’s Fashionable Nonsense—is now 16 years old. Anthropology is not at a critical intellectual juncture, as Whitehead claims. That juncture is more than a decade in the past. The decision anthropology now faces is whether to backtrack and find some genuinely fruitful approach to studying humanity, or else continue down this postmodern/posthuman path, which we already know is a cul-de-sac. As for Homo sapiens, we, like anthropology, face serious threats to our long-term survival. We will know when the posthuman era is upon us not because we have read Human No More, because we won’t be around to read any books at all. ![]()