In this week’s eSkeptic:

- Lecture this Sunday: Dr. Daphne J. Fairbairn on Extraordinary Differences between the Sexes in the Animal Kingdom

- YouTube Video: The Perks of Paranoia, by Christopher Griffin

- Follow Daniel Loxton: Skeptics are Not Everythingologists

- Feature Article: Growing Up in the Amityville Horror (a movie review)

Our Next Lecture at Caltech:

DR. DAPHNE J. FAIRBAIRN

Odd Couples: Extraordinary Differences between the Sexes in the Animal Kingdom

with Dr. Daphne J. Fairbairn

Sunday, May 19, 2013 at 2 pm

WHILE WE JOKE that men are from Mars and women are from Venus, our gender differences can’t compare to those of other animals. For instance: the male garden spider spontaneously dies after mating with a female more than 50 times his size. Female cichlids must guard their eggs and larvae—even from the hungry appetites of their own partners. And male blanket octopuses employ a copulatory arm longer than their own bodies to mate with females that outweigh them by four orders of magnitude. Why do these gender gulfs exist? This lecture, based on her book, explores some of the most extraordinary sexual differences in the animal world. From the fields of Spain to the deep oceans, evolutionary biologist Daphne Fairbairn uncovers the unique and bizarre characteristics that exist in these remarkable species and the special strategies they use to maximize reproductive success. Fairbairn also considers humans and explains that although we are keenly aware of our own sexual differences, they are unexceptional within the vast animal world.

The Perks of Paranoia

Myths. Conspiracy Theories. Illusory Correlation. Do these things have an evolutionary basis in common? What type of thinking enables conspiracy theorists to correlate ideas that in truth have nothing to do with each other? In his book, The Believing Brain, Michael Shermer refers to these types of thinking as patternicity — finding meaningful patterns in meaningless noise.

In this video project by Christopher Griffin, a senior Graphic Design student at the California College of the Arts (San Francisco), these pattern-seeking ideas are visually illustrated, as if diving head-first into the mind of a true believer.

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

Skeptics are Not Everythingologists

Daniel Loxton reflects upon the dangers of speaking beyond one’s expertise—a danger no less serious for skeptics than for fringe science proponents.

Modern Skepticism’s Unique Mandate

Daniel Loxton looks at the 1976 birth of scientific skepticism as an organized modern project, and asks: If other movements already promoted humanism, atheism, rationalism, science education, and even critical thinking, why did skeptics find it necessary to organize an additional, new movement called “skepticism”?

About this week’s eSkeptic

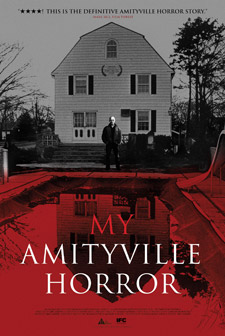

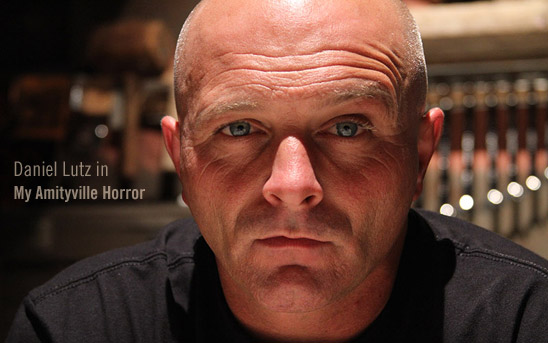

In this week’s eSkeptic, Trevor Fehrman reviews Eric Walter’s documentary film My Amityville Horror (IFC Films 2012), in which, for the first time ever, Daniel Lutz delivers his perspective on perhaps the most famous ghost story in America: the 1975 Amityville haunting.

Trevor Fehrman is a native of the Twin Cities (Minneapolis-St Paul, MN). His involvement in the local theater scene improbably landed him on a television show alongside Nathan Lane. He worked as an actor in television and film for many years before moving to Berkeley to study literature and write. He contributes a column to Film Racket called The Contrarian.

Growing Up in the Amityville Horror

by Trevor Fehrman

The principal subject of Eric Walter’s superb documentary, My Amityville Horror, is a ghost. His restless, estranged spirit flickers and moves past us like a projection, doomed every day to relive the ordeal which finally drove him beyond the land of warmth and living things. He’s a shade, a shadow, a churning confluence of ireful energies. His name is Danny Lutz. He works as a UPS delivery man. In his free time he plays passable, if vapid riffs on a tacky electric guitar. He sees dead people. Or…at least he saw them, anyway.

My Amityville Horror is largely composed of extended interviews with Danny in which he gives, for the first time ever, his perspective on what is probably the most famous ghost story in America. Danny, now a stocky, bald, middle-aged man with a volatile, blue-collar demeanor and a smoking habit, was only a 10-year-old boy at the time he lived in the Amityville house that became the greatest ghost story in recent memory. During his short stay in the house on Ocean Avenue, a time he describes as “like being awake in your own dream,” he claims to have been possessed, thrown up a flight of stairs by an unseen force, swarmed by hoards of flies, had a window magically smash his hand so forcefully that he describes the injury to his fingers as “skin on skin” (though it was miraculously healed later that night), witnessed glowing red eyes through a second-story window, strange smells, temperature changes, odd garage door behavior, mysterious green slime, and other spooky flotsam and jetsam.

His claims don’t end there, however. He also claims to have hated his step-father, George Lutz, with the fury of hellfire. He says George forced him and his mom to move to Amityville in the first place, and that George forced Danny to change his last name to his own, that he made Danny call him “Mr. Lutz” or “Sir,” and that George kept books on “hypnotism”, “Buddhism,” “mind control,” and “the occult” on his personal bookcase. He claims that both his mother, Kathy Lutz, and George on more than one occasion beat him and his siblings with wooden spoons then made them march about the house like soldiers. He claims there were repeated violent outbursts.

He claims to have tried to kill George, and that he’s happy George is now dead. He claims that he “believes there is such a thing as evil,” but it seems Danny’s evil is a device of Satan and not the human heart. He claims that after he begged his mother to let him leave home for years, she finally acquiesced when he was fifteen. He claims that before he left to go live in the desert, sometimes sleeping under the stars, sometimes on friends’ couches, she made him a few peanut-butter and jelly sandwiches and washed some of his socks.

Depending on how you ask the question, somewhere around half of all Americans believe in the existence of ghosts. According to one poll done by CBS, 22% of Americans claim to have actually “seen or felt the presence” of one. Why do so many people believe? A desire to believe that the soul persists after death, a desire to believe that our presence will still be felt on earth after we’re gone, the desire that there should always be retribution for evil actions, and that humans have an evolutionary tendency to essentialize things, or believe that an “essence” exists beyond material substance.

From a skeptical perspective, if we take it as a given that Danny Lutz didn’t actually get thrown up the stairs by a poltergeist then we’re left with three possibilities.

The first is that Danny was hallucinating, but that’s probably not right. Today, Danny is a testy, sometimes explosive person, but there’s no evidence that he’s insane. He doesn’t see ghosts anymore (and, tellingly, hasn’t since he felt like he was in control of his own life), he holds down a job, he’s able to drive on the right side of the road, file his taxes, and carry on conversations like any normal person might. Not only that, Danny wasn’t the only person who claimed there were ghosts in the house.

The second explanation is that Danny has been perpetrating a con these last 40 years, but that’s even less likely. First of all, Danny hasn’t profited much from this. Unlike George and Kathy Lutz, who enjoyed a brief period of talk show appearances and world speaking tour, Danny sees the entire experience as a burden. He’s tried to keep the fact that he was one of the children in the Amityville house on the down-low for most of his life. He says that when people find out, he’s inundated by inane questions and mild forms of harassment. That, at least, isn’t terribly hard to believe.

The third explanation, which is both the most plausible and the most interesting, is that Danny really thinks he’s telling the truth, at least for the most part. We’ll note first that he has both a tendency to exaggerate and an accompanying tendency toward extreme credulity. Take the window smashing incident: Danny says that his hand was so swollen it looked like “a child’s baseball glove” and that it was “five times” its normal size. In an oddly touching reunion, when his mother’s friend Lorraine (a devout Catholic who has always believed Danny’s claims and declares that she gets visited by the spirits of various holy figures) takes out a crucifix which she says is embedded with a piece of wood from Jesus’ cross, it never occurs to Danny to ask how she came into possession of such a priceless artifact, why it’s not in a museum, its provenance, etc. He simply mouths the word “wow” at the documentary crew. During another conversation (this time with reporter Laura DiDio, one of the first to cover these events back in the 1970s) we hear about a trip to the doctor in which Danny tells him how he witnessed George move a wrench with his mind in the garage—this was before Amityville, by the way. The doctor met with Danny’s mother for a few minutes afterwards and then she and her son drove silently home. Laura responds by pointing out “Right, ‘cause, most doctors would say…” but then Danny interrupts her, completing her sentence with an unhinged confidence: “Get a new boyfriend!” She replies, “Or…this kid needs tests.”

A practical introduction to the techniques of skeptical scholarship and investigation. Joining classics like James Randi’s Flim-Flam! and Joe Nickell and Robert Baker’s Missing Pieces, Ben Radford’s Scientific Paranormal Investigation takes readers inside scientific skepticism’s proudest tradition. … Scientific Paranormal Investigation is highly recommended for anyone considering any sort of skeptical research. Indeed, it should almost be mandatory.

Through a combination of the plasticity of memory (of your garden variety, but also the kind the world became familiar with through the tragic Michelle Remembers debacle), fossilized embellishments, groupthink, general credulity, a traumatic upbringing in which the existence of ghosts was accepted as fact, as well as several other factors, we can construct a reasonable hypothesis as to how Danny became convinced of things which are impossible. And the real question becomes: once you begin an invention of that scale, and the whole country watches, how do you stop it? Well, if you’re a child, maybe the sad truth is that you can’t. And so it becomes a part of you—invisible, but moving through you, influencing everything you think and do. You become haunted by it.

Many who believe in ghosts will ask: “Well, what’s the harm? What does it matter if I believe in ghosts? Who does it hurt?” It could be they really think they saw one, or have a friend who did. It could be they have a distorted idea of what it means to be open-minded. Maybe it’s mildly entertaining for them to believe it. Maybe it comforts them in some strange way. Maybe they don’t even know why they cling to the idea but can’t particularly be bothered to figure it out. I’d offer a compromise: hauntings are indeed very real. We can be haunted by our regrets, our past traumas, our unfulfilled ambitions, and the personas we’ve built for ourselves and now can’t escape. And maybe, for some, the aggregate entertainment and comfort of 150 million people or so is worth the permanent emotional disfigurement of one little boy, but of course it isn’t just the one. Anyway, it wouldn’t be worth it to me even if it was. One haunted child is one too many.