In this week’s eSkeptic:

- Our Next Geology Tour: Area 51 and Alien Landscapes (Jan. 18–20, 2014)

- Lecture this Sunday: Donald Prothero—Abominable Science & Reality Check

- Explore the Galapagos: Retracing Darwin’s Voyage (Jan. 3–10, 2014)

- MonsterTalk: Speak of the Devil

- Feature: The Stuff of Nightmares: James Van Praagh and the Afterlife

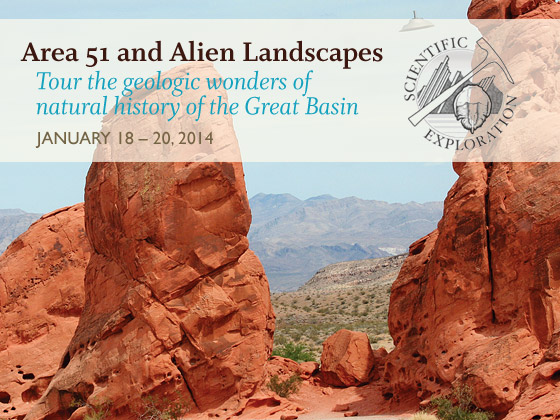

Area 51 and Alien Landscapes

January 18–20, 2014

COME JOIN THE SKEPTICS SOCIETY for an exciting trip to the wonders of southern Nevada. We will travel along the Extraterrestrial Highway near the north gates of Area 51, and have lunch at the famous Little A’Le’Inn in Rachel, Nevada. We will take a tour of the National Atomic Testing Museum in Las Vegas. In addition, we will visit the stunning alien landscape of Valley of Fire, collect 520 million-year-old trilobites, and revisit the Old West at Calico Ghost Town. Come join us and see some of the most amazing scenery in the world! Seats are limited, so make your reservations soon!

Click an image to enlarge it.

What’s Included?

Tour package includes charter bus, two nights’ lodging in Las Vegas, all breakfasts and lunches, natural science lectures en route, museum and park fees, and a tour guide booklet. Your trip fee also includes a $150 tax-deductible donation to the Skeptics Society.

Questions?

Email us or call 1-626-794-3119 with a credit card to secure your spot.

Lecture this Sunday

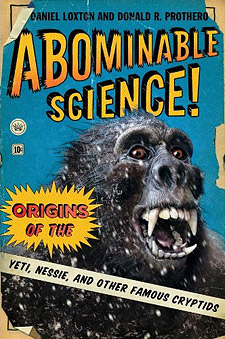

Abominable Science & Reality Check

Sunday, November 17, 2013 at 2 pm

Baxter Lecture Hall

GEOLOGIST, PALEONTOLOGIST, EVOLUTIONARY THEORIST AND SOCIAL ACTIVIST in the name of science and skepticism, Dr. Donald Prothero talks about his two new books that deal with battles over evolution, climate change, childhood vaccinations, and the causes of AIDS, alternative medicine, oil shortages, population growth, and the place of science in our country. Many people and institutions have exerted enormous efforts to misrepresent or flatly deny demonstrable scientific reality to protect their nonscientific ideology, their power, or their bottom line. To shed light on this darkness, Prothero explains the scientific process and why society has come to rely on science not only to provide a better life but also to reach verifiable truths no other method can obtain… READ more

A book signing will follow the lecture.

The views expressed by the speaker are solely those of the speaker. The content of this presentation does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the California Institute of Technology and should not be taken as an endorsement.

Order the books from Shop Skeptic

and have them signed at the lecture

Don’t Miss December’s Lecture!

How To Boldly Go into Space: An Insider’s Look into How Space Missions are Created, Funded, Built, Launched, and Run

with Dr. Linda Spilker and Dr. Thomas Spilker,

Sunday, December 8, 2013 at 2 pm

Baxter Lecture Hall

DRAWING ON THEIR DECADES OF WORK FOR NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) Drs. Linda and Thomas Spilker give us an inside view of what goes into the unmanned space program, from the origin of a space mission, to how the funds are found to finance it, to how the spacecraft is designed and built, and to the launching and running of such a mission, often designed to last for years and even decades… READ more

Retracing Darwin’s Voyage

January 3–10, 2014

Only One 2-person cabin left!

To reserve, contact Victoria Gray at 202-518-2324

or via email at v.gray@comcast.net.

JOIN US FOR A UNIQUE OPPORTUNITY to explore the Galapagos with Darwin scholar and MacArthur Fellow Professor Frank Sulloway, and Skeptic magazine editor Michael Shermer. Professor Sulloway will share his unique perspective and research developed as a result of more than a dozen visits to these islands in 40 years. He has published extensively on Darwin’s visit to the Galapagos, and has retraced Darwin’s route on all four islands that Darwin visited. Professor Sulloway has also conducted research on evolutionary aspects of Darwin’s finches. Michael Shermer is author of Why Darwin Matters: The Case Against Intelligent Design (2006), as well as a biography of Alfred Russel Wallace, who codiscovered the theory of natural selection in 1858. With Professor Sulloway, Dr. Shermer has also participated in field research in the Galapagos, documenting Darwin’s activities on San Cristóbal, the first of the four islands that Darwin visited in 1835.

Explore a different island in the archipelago each day of the expedition with Professor Sulloway, Dr. Shermer, and one of the National Park’s best guides, Juan Tapia. Every evening they will preview the visit and attractions for the following day, including sites visited by Darwin.

Darwin had the Beagle, and our group will be chartering the Beluga. This sleek motor vessel was built in 1996 and was completely refurbished in 2002. Her eight double cabins all have private bathrooms and hot water showers. The vessel includes several amenities to ensure your comfort: A library, a TV area, a restaurant/bar, and a sun deck. Dr. Sulloway has worked extensively with this charter company over the last four decades.

The fare is $7,375 per person for the Galapagos. This includes two nights in Guayaquil, a United Nations World Heritage Site and round-trip airfare to/from Guayaquil to the Galapagos. A portion of the cost per person is tax deductible.

Speak of the Devil

Robert W. Price

MonsterTalk welcomes back Bible scholar Robert M. Price to discuss the biggest and most well known villain in Western culture: Satan. Who is this character and how has he changed over the history of Judeo/Christian religions? From servant of God to dark villain, we track the evolution of the Devil.

Get the MonsterTalk App

About this week’s eSkeptic

In this week’s eSkeptic, Ingrid Hansen Smythe wittily dissects the farcical visions of the afterlife presented by James Van Praagh in his book Growing up in Heaven.

Ingrid Hansen Smythe (BMus, BA, MA) is a freelance writer, playwright, and the author of three books—Dwynwen’s Feast, Stories for Animals, and Poetry for Animals. Visit her at www.ihsmythe.ca.

The Stuff of Nightmares

James Van Praagh and the Afterlife

by Ingrid Hansen Smythe

There are a number of different methods of exposing an individual as a liar and a charlatan. One way is to engage the person directly in their self-professed area of expertise and then judge their performance. You might employ an alleged brain surgeon, for example, and pay that person to perform brain surgery on you—and if the surgeon uses a cork screw and salad tongs, and the operation turns into something akin to an autopsy or a dinner party at the Todd’s (Sweeney, that is), you’ve got fairly good evidence against the so-called expert. Alternatively, you could spare yourself the agony of direct engagement and read the published papers of the brain surgeon in question. If the papers are full of contradictions, wild inaccuracies and obvious fictions—if the surgeon believes that the hippocampus is an actual college, for example, or that olfactory bulbs are planted in the spring, or the ventral horn is a member of the brass section—again you have solid evidence that the brain surgeon hasn’t a clue and is not actually all that interested in the contents of your skull but, rather, in the contents of your wallet.

In his brilliant exposé of James Van Praagh, author Miklos Jako uses the first method and actually pays the renowned medium $700 for a reading. (Watch the reading with Jako’s editorial.) In tallying up the hits (12) and misses (64), Jako calculates a success rate of 16 percent. This is remarkably low, even for a cold reading, and Jako might have gotten a higher success rate had he engaged Bubbles the chimp. Worse yet, Jako actually feeds Van Praagh a lie about his father being involved in a drunk driving accident, and Van Praagh falls for it hook, line, and sinker. “He keeps going on about how he was very sorry it hurt you,” says Van Praagh. “He knows he embarrassed you on several occasions. He’s ashamed of that. He’s ashamed. He’s sorry, he’s ashamed of that. And please don’t think of him that way.” Jako’s outrage is palpable at this point, and it’s tough for him to remain composed. “My father never embarrassed me,” he says firmly. “Never.” Based on the evidence, Jako goes on to add his dead-on-the-mark assessment of the great psychic. “James Van Praagh,” he says, “you’re full of shit.” This sums things up nicely, I think.

You’d imagine that this masterful unveiling would settle the matter once and for all—but no. The critic can always assert that the old brain tumour was acting up again and that Van Praagh was simply “off” on that particular day, or that he was subconsciously stifled by Jako’s Kryptonite-like skepticism, or that an alleged error was just a silly misunderstanding, or that the spirits were being deliberately impish and uncooperative. None of this is Van Praagh’s fault. Thus, even when a medium is wrong more often than right, support continues or even increases.1

Unlike Miklos Jako then, my approach is to use the second method, examining the writings of Mr. Van Praagh in detail to see if I can detect anything that confirms Jako’s assessment. I’ll be analyzing his book Growing Up in Heaven, Van Praagh’s singular study of the afterlife as it relates, specifically, to the deaths of children. In it, Van Praagh shares his actual conversations with dead children, his interactions with the grieving parents, his philosophical intuitions, and his revealed insights into the afterlife for those of us dying to know what really goes on behind the veil.2

Before proceeding with the specifics, allow me to briefly sum up Van Praagh’s metaphysical position. Each of us is an eternal soul that reincarnates on the earth, and on other planets and in other dimensions, in order to learn all the lessons a soul’s got to know. These lessons are, predictably, things like patience and humility, and not things like how to make napalm or take the temperature of a cat. The ultimate lesson is that “we are all love created by Love,”3 and once we’ve figured out what the hell that could possibly mean, we achieve enlightenment. Our karma guides us reliably to the perfect body in which to learn that next big life lesson, but before we reincarnate, we plan out our next life with others in our soul group. The soul group is composed of souls that share the same electromagnetic frequency4 and is divided into soul families that are made up of soul mates and others who interact with us on a daily basis. We make soul pacts with these people, meaning that we promise to help them to achieve their goals in their upcoming existence. Thus everything is planned, nothing is an accident, and no one ever dies before it is time.

About 29,000 children die every day,5 and although this sounds like a depressing statistic, keep in mind that in Van Praagh’s worldview not one of these children is actually dead. There is no death. There is only deportation. Essentially, the unfortunate child gets a sudden transfer from one home to another, and one school to another (because there’s still school in heaven—sorry kids!). This forced, noncorporeal relocation is hard on loved ones left behind, but the child is inevitably portrayed as happy in its wholesome new surroundings where it can study what it wants in school, communicate telepathically, play with the other non-dead kids, and zip around wherever it desires simply through the power of thought. Van Praagh’s description of heaven reads like a brochure for a boarding school:

Besides attending school, children entertain themselves with a wide range of activities like sports, games, and handicrafts. They enjoy swimming, cycling, gardening, baseball, woodcarving, sailing, and anything else they desire. … Some become members of organizations similar to the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts that teach leadership skills, teamwork, arts and crafts, conservation, and camping.6

Nice! It sounds like God really knows how to run an afterlife. I note, however, that Van Praagh doesn’t mention computers, video games, TVs, or technology of any kind, and it’s hard to imagine the 21st century child content without a single app. Woodcarving is no substitute for Call of Duty, and one imagines a teenager going into shock when it suddenly has nothing to do with its thumbs.

A more careful analysis reveals other flaws in Van Praagh’s whimsical vision. Children are depicted as being essentially like they were on earth but with various superpowers like teleportation, which leads to the obvious point that a world where kids can zip around just by thinking about where they want to go would be utter chaos. One moment Timmy’s at the handicrafts table, the next moment he’s sailing on the Styx. Plus, in heaven, “every idea is exchanged through thought. As soon as a spirit thinks, its thought is manifested and becomes a reality!”7 The cacophony of several billion trains of thought chugging along and manifesting their crazy-ass visions would be hellish, of course, plus spirits can be “bogged down in negative human emotion. If whatever they are thinking manifests, every spirit around them can see and feel what they are thinking.”8 Horrors! Telepathic adults would have a hard enough time preventing themselves from bringing into being all manner of inappropriate manifestations (Cthulhu, a mountain range of breasts, a million Benedict Cumberbatches), but with selfish, hamster-brained children it would be all that much worse. Imagine the conflicts arising between children’s competing manifestations, and I’d give heaven five minutes before it’s filled to overflowing with Lego and My Little Ponies, and turned into a candy and unicorn-filled laser-tag bouncy castle.

The contradictions in Van Praagh’s schema abound. We are told, for example, that a soul is ageless, and also that there are young souls, mature souls, and old souls.9 An ageless old soul is an oxymoron, surely, and it’s hard to understand how an ageless soul can “evolve rapidly” as Van Praagh claims.10 We are told that a soul cannot be hurt or harmed,11 and yet there are damaged souls.12 We are also told that “[t]he astral dimension is a world without time.”13 Van Praagh explains: “In Spirit, there is no time; there is only now. Past, present, and future are simultaneous.”14 Thus, on the one hand, we are told that little Timmy can become a Boy Scout in heaven, but on the other hand, we’re told that the whole time-concept has been cancelled, which surely renders the enterprise of earning merit badges incoherent. Coin collecting, dog care, fly-fishing—they all rely on a sequence of events, as does everything else Van Praagh describes in heaven. Luckily we’re also told that “time is relative on the spiritual plane”15—a clear contradiction of the “no time” policy. So time is relative, and it doesn’t exist, and it does exist because it must in order to make Van Praagh’s description of heaven even halfway intelligible.

In another contradiction of the ageless soul idea, we are told that children who die as babies or toddlers spend their time in celestial nurseries. This is reflected in the following poem:

In a baby castle just beyond my eye

My baby plays with angel toys that money cannot buy.16

Reading this poem is like getting hit over the head with a sack of sugar and sums up well Van Praagh’s hokey, cornball vision of what heaven is like. It’s as if, after you die, you become a cast member of The Waltons and live forever in a Hallmark made-for-TV movie. It would seem that this happens even before you officially pass over the rainbow bridge, as evidenced by this exchange with 7-year-old Kylie, who is dead and spending the day hanging out at a funeral home. “Hi Mister,” she says to Van Praagh. “The lady with the pink dress and pretty smile is ready to bring me home. There is a pony waiting for me there. I can’t wait!” Van Praagh asks her name, and when she says “Kylie,” she then adds, “Isn’t it a pretty name? Oops, got to go now! The shiny lady is waiting for me.”17

A person could get diabetes reading this kind of prose, but the bigger issue is that it’s obviously so made up. The pony cliché is just funny, but it’s weird that Van Praagh can be so oddly deaf to the way children actually speak. “Isn’t it a pretty name?” is not a remark a kid would make about her own name. Nor would a school-age child, when asked what he’s doing in heaven, reply, “Growing and growing and growing!”18 No child has ever said this. Growing is not an activity. Children also don’t say things like, “He wants me to let you know he has met Old Man Stebbins”19 (a family friend) because no one has been called Old Man Stebbins since about 1912, but a quick Google search reveals the name “Old Man Stebbins” in William Hawley Smith’s story The Evolution of Dodd. This is suspicious, of course, and makes you wish Van Praagh would come up with something a little more original. Further, not only does Van Praagh not know how kids talk, he doesn’t seem to know what they’re actually like. “Have you ever noticed that a child who is sick is more concerned about its parents’ welfare than its own?” he asks. No, James. No I haven’t.20

In addition to the mawkish and cloying nature of the afterlife, however, there are also aspects that are just plain creepy. The worst of these is this: your dead children are watching you. “Even though the child may no longer be in the physical shell,” says Van Praagh, “it will watch its earthly parents from the heavenly world.”21 And, although kids are supposed to be in school or at camp or wherever, Van Praagh channels one child who has this to say: “Just tell Mommy and Daddy that I’m still alive, and I can see them all the time.”22 All the time! There’s a cure for your porn addiction. “Your [dead] son says he was with you in the garage the other day,”23 Van Praagh tells one father, as if this macabre revelation is supposed to be comforting and not like a scene from The Shining. And it’s not just mom and dad who are under constant surveillance. Van Praagh channels one dead boy who says that he is watching his sister from heaven. “I will take care of her, he promises.”24 It’s not clear how he intends to do this, but it is clear that he’s violating several sections of the criminal code and, if he were alive, there’d be hell to pay.

The idea that this brother is watching his sister is even more disturbing when you realize that people in soul families often trade roles. It’s as if the same group of people are put in a Yahtzee cup, and next life you might find yourself giving birth to your own grandfather. Van Praagh explains to a girl whose brother has committed suicide that she couldn’t save her brother in a past life either—a past life in which she was his lover.25 Apparently it’s not incest if it happens in another life but, as for me, if I were told that I was my brother’s lover in any life, I would need to hire a personal assistant to file all the feelings I would have about this.

This monstrous vision is further enhanced by the idea that our dead children are trying to communicate with us. How do they do it? Funnily enough, they do it the same way it’s done in horror movies. Dead kids often manipulate electrical devices, for example. Van Praagh explains:

Electricity is another very common method used by spirits to contact us. Because everything is made up of electromagnetic energy, spirits are able to focus their thoughts to manipulate the electromagnetic field around various electrical objects. In this way, they are able to turn on or off anything that utilizes electricity—appliances, lights, televisions, computers, radios, microwaves,26

sex toys, and more! I admit that I added sex toys to the list, but if it’s electric, there’s no reason why Timmy can’t haunt it. Surprise! Dead kids also create special smells (just like when they were alive!), come to us in our dreams (Boo!), and appear as indistinct—one might almost say meaningless—spots of light in photos. They also communicate through special signs, and one woman relates the story of how her dead husband, who shared her love of dragonflies, caused one to appear and stay on her car windshield for half an hour while she was driving down the freeway. The woman was deeply moved by this sign from the great beyond, but surely the story would have had greater impact if the woman and her husband had shared a love of goats, say, and one of those had suddenly appeared on her windshield while driving. Finding a dragonfly on your windshield is like finding a parking ticket—pretty damned ordinary—but finding a goat is something that would give even the crustiest of skeptics pause.27

Spirits can’t possibly spend all their time plastering insects to windshields or woodcarving and whatnot because, at some point, they need to get cracking on their soul pacts. A soul pact is “an agreement made in the spiritual realms before we incarnate into human form” in which “each soul involved must give its consent to take part.”28 Here is how Van Praagh envisions one example:

A man is running late for a business meeting; he has been warned many times not to be late. In his effort to be on time, and because his mind is anxious about the consequences of being late yet again, he runs a red light, plows into a school bus, and kills several children. Had he been more aware of his soul pattern of irresponsibility—running late—he might have started his trip earlier and avoided a collision. We could argue that he caused the death of those children. On the other hand, we could look at it from a different point of view. Perhaps a soul pact existed between the advanced souls of the dead children and the man who collided with the bus. Perhaps, on a spiritual level, they agreed to assist him to change his pattern. I know this is difficult to understand with our human minds. Let’s just consider the possibility that, because of the accident, this man realizes the tragic results of his irresponsible behavior and decides to turn his life around. He leaves his job and volunteers to help orphaned children.29

Don’t ask how the elaborate dance between all of these people is supposed to be choreographed over a lifetime. Just imagine this roundtable conversation in the before-life between Lenny (who is always late) and some of the members of his soul group, especially Pedro:

Lenny: I need a few of you to help me learn not to be late for meetings.

Pedro: So what do you need us to do?

Lenny: I need a bunch of you to die horribly.

Pedro: Really?

Lenny: Afraid so. I need a few of you to volunteer to get killed—as children—in a horrific road accident. So put up your hand if you’re interested in teaching me to use a watch.

Pedro: Couldn’t you just resolve to be on time rather than committing involuntary manslaughter?

Lenny: No, I don’t think so. I think once I see your mangled bodies strewn across a roadway, I’ll take being on time just a little more seriously.

Pedro: Couldn’t we be a coach full of really old people out on a day trip or something?

Lenny: No, sorry. The best way to learn to be on time is by killing a bunch of kids.

Pedro: But won’t that impact a lot of other people—you know—maybe the families of the kids? Won’t that create a lot of unimaginable grief?

Lenny: Listen, I have got to learn to be on time for meetings. I can’t believe you’re not taking this seriously.

Pedro: No, we are, it’s just…well, how exactly is killing us going to result in you being on time for meetings?

Lenny: I’ll leave earlier, drive slower. Plus I’ll quit my job and volunteer at an orphanage to make up for everything I’ve done.

Pedro: How is that good? I mean, being on time for meetings was a work-related problem in the first place. Plus how are you going to live without a job?

Lenny: Okay, let’s not get caught up in the niggling details here, people. Let’s focus on my time management issue, okay?

Pedro: It’s just—I’m wondering, if you drive into a bus, aren’t you the one who’s going to get killed? I mean, a bus is a pretty big thing. What are you going to be driving—a tank? Maybe that’s why you’re always late—maybe you could invest in a zippy little sports car and an alarm clock.

Lenny: Does a soul pact mean nothing to you people?

Once again, Van Praagh sets up a scenario that, on sober second thought, reveals itself to be absurd beyond belief. Soul pacts, haunting loved ones through signs and smells, constant surveillance by the dead—it’s all too much. Like a sour gummy worm, Van Praagh’s vision of the afterlife is saccharine, bitter, and creepy all at the same time.

Still, what’s wrong with a little fabrication if it makes people happy? What’s wrong with telling them what they want to hear? “You were a great dad—the best,” says one child channelled through Van Praagh. “He thanks you for that. He says he loves you both very much. He wants you to know that. He says he picked you especially as his parents and wants you to know that you will always be together.”30 Channelling another child, Van Praagh says, “He wants you to forgive yourself. You did nothing wrong. Do you understand? You’re not to blame, he is saying.”31

Of course, no child from the Great Beyond ever says, “You know, I never liked you. Never. As parents go, you two were the absolute worst. I’m surprised I lasted as long as I did with your cooking. And we both know it’s your fault I’m here. I told you that babysitter couldn’t be trusted but you never listen to me.” Van Praagh gives people the same message time and time again. Your child loves you. Your child is watching you and can hear your thoughts. Your child is interacting with you through flickering lights, messages on billboards, smells, orbs in photos, and by playfully hiding your belongings. Everything happens for a reason. You were not a negligent asshole. Move on. Be happy.

To be fair, a person who believes in immortal souls believes that all people—even after death—exist in the present tense, and therefore there is always the nagging worry—where is my loved one now? Is my loved one okay? For people who believe in souls, therefore, Van Praagh’s words may provide comfort and be exactly what they want to hear. However, it should be said—and often is—that if Van Praagh is lying to distraught parents, and if he’s making money off it, this is what’s called fraud and it’s hard to see how that’s not illegal. And, the levity of the preceding paragraphs aside, let’s not forget how serious a moral outrage this truly is. Here are the words of a grieving father, four months after the death of his 17-year old daughter:

This is the hardest thing I have ever faced. Much harder than watching my father slowly die from prostate cancer. That made me sad and angry, but nothing compared to this. This is an ocean of grief. I’m treading water in a tidal wave of pain, disbelief, anger, sadness, waves and waves of heartache. … If I focused on her death, I’d go insane.32

Van Praagh makes his money off people who are close to insane with grief. And what does he offer them? Here’s a description of what he tells a grieving couple at one of his shows: their son wants to convey the urgent fact that he really liked the special heart-shaped wreath with his picture on it that they put on his grave (as if any kid in history has ever given a rat’s ass about a wreath). The boy holds up a blue ribbon with #1 Mom on it, points to a football jersey (he played football), informs his parents that his dead dog was waiting for him in heaven, and advises them not to kill themselves because he’s in a better place.33 Note that, although the dead boy is now a timeless entity and can zip into the future on a whim, he does not see fit to reward his #1 mom with winning lottery numbers, nor does he advise his parents not to take that last fatal canoe trip. In Van Praagh’s world, the one truly vital fact about the boy—he’s dead—is the one fact that is denied.

This may be an underpowered vision, the critic might argue, but at least it’s something. What does the unbeliever have to offer that’s any better? Well, here’s one possibility, among many: Consider the fanciful, but nonetheless true, notion that a human mother is a living archive of every child she’s ever conceived. Consider fetomaternal microchimerism, in which cells from the child work their way back through the placenta and into the mother’s body during pregnancy, and that these cells are found throughout the body and are very often clustered at the site of an injury. It’s as if the pregnant woman receives a placental stem cell transplant, though it isn’t entirely clear yet what these cells are up to. What is clear is that a mother carries with her the DNA of every one of her biological children, possibly for her entire lifetime. This means, of course, that she also carries the DNA of the father (or fathers) of those children. It’s all there inside her body—a permanent and living record of motherhood.

If you were a grieving mother, I would want to tell you of the possibility that you and your child are forever intertwined, and that living cells carrying your child’s DNA circulate in your very life’s blood. I would tell you that your daughter, say, is in your heart, and not just metaphorically; the very cells with her unique DNA sequence may literally be in your heart where there’s a good chance they’re playing a protective role. Your hearts, in this very real sense, may be beating as one.34 I would tell you of the possibility that your son, say, is in your mind and, as in life, is still a part of your flesh and blood. Are these cells in some way thinking with your brain? If they are, it’s as good as saying that your son is a part of your very consciousness. Whatever is going on, your child is not out there somewhere, causing the lights to flicker and the cat to hiss. Your child is still a part of you, and you are mysteriously united in ways that you can never fully know.35

This notion is a poetic one, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t true. It’s just what the science tells us. As a mother, I find the idea unspeakably beautiful. As for Van Praagh’s vision—I find no grandeur whatsoever in this trite and hackneyed view of life.

But, it might be asked, why can’t grieving parents do both—believe that their child is inside of them in one sense and also in heaven in another? Of course grieving parents are free to believe anything they want, no matter how far from reality it might be. “It’s said that losing a child is the hardest thing a person can experience and if there is something worse I can’t imagine what it could possibly be,”36 says one bereaved father. So yes, of course, parents get a free pass and can believe whatever is necessary to get through their hellish journey. All I’m saying is just don’t give James Van Praagh any money. Don’t give him $700 to tell you that your child (whose name begins with an E, or whose name has an E in it, or who knew someone with an E in their name) is in heaven riding a pony with the shiny lady. Your child may, in fact, be riding a pony with the shiny lady but, if she is, James Van Praagh doesn’t know it.

“It is a curious thing,” wrote Evelyn Waugh, “that every creed promises a paradise which would be absolutely uninhabitable for anyone of civilized taste.” Those words were never truer than in the case of Van Praagh’s farcical vision of the afterlife. But what if Van Praagh is right? What if the afterlife is just as he describes? Then, for heaven’s sake, don’t die. Or, at the very least, make it the last thing on your list. Meanwhile, you’d better shape up and stop with all the disgusting habits already. After all, who knows how many dead people are watching you right this second? Actually, I think I know. I think you and I both know the exact number, to the decimal place. And in my more cynical moments, I have to wonder—does James Van Praagh know it too? ![]()

References

- Despite the Amanda Berry debacle (in which psychic Sylvia Browne claimed that Berry was dead when she wasn’t), business appears to be booming for Browne and she even has a cruise called the Mystical Voyage At Sea planned for 2014. http://www.sylviabrowne.com. Skeptics: don’t forget your sick bags!

- I use the phrase “dying to know” with intent, since dying is the only reliable way for the committed empiricist to know anything about the afterlife. It’s just too bad that being dead means that you don’t have a brain anymore, and not having a brain makes thinking tricky, but this is the great paradox.

- James Van Praagh, Growing Up in Heaven. New York: HarperOne, 2011, p. 10.

- Ibid., p. 75. Souls are electromagnetic, according to Van Praagh, and this is good news for the energy sector. Plus, this is a testable claim—if souls are electromagnetic, scientists should be able to detect them. Let the rush to secure grant money begin!

- And that’s just children under age 5. http://www.unicef.org/mdg/childmortality.html

- Van Praagh, p. 53.

- Ibid., p. 35.

- Ibid., p. 35.

- Ibid., p. 81.

- Ibid., p. 125.

- Ibid., p. 106.

- Ibid., p. 72.

- Ibid., p. 34.

- Ibid., p. 115.

- Ibid., p. 125.

- Ibid., p. 111.

- Ibid., p. 8.

- Ibid., p. 205.

- Ibid., p. 55.

- Ibid., p. 99.

- Ibid., p. 20.

- Ibid., p. 31.

- Ibid., p. 13.

- Ibid., p. 51.

- Ibid., p. 74.

- Ibid., p. 142.

- Ibid., p. 145. On second reading, I see that it was actually the side view mirror that the dragonfly clung to for dear life, a version of the story that raises suspicion and leads to this question: What motivates a dead husband to make a special sign appear just outside of his wife’s field of vision while she’s zipping down the freeway at high speed? It sounds to me like theirs may have been a complicated kind of love.

- Ibid., p. 21.

- Ibid., p. 91–92.

- Ibid., p. 94.

- Ibid., p. 18.

- http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/glen-canning/rehtaeh-parsons-father_b_3720710.html

- Van Praagh, pp. 94–95.

- Or your daughter’s cells may be creating havoc—just like when she was alive!

- There are many articles available online on the subject of fetomaternal microchimerism. See for example:

- http://www.livescience.com/23490-fetal-dna-mom-brain.html

- http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn21185-fetus-donates-stem-cells-to-heal-mothers-heart.html#.Ujz4fyTlGL2

- http://singularityhub.com/2013/02/05/new-studies-show-cells-from-fetus-end-up-in-mothers-brains-and-hearts/

- http://www.the-scientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/32678/title/Swapping-DNA-in-the-Womb/

- http://circres.ahajournals.org/content/110/1/3.full

- Glen Canning. http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/glen-canning/rehtaeh-parsons-father_b_3720710.html