In this week’s eSkeptic, Michael Shermer reviews Will Storr’s book, The Unpersuadables: Adventures with the Enemies of Science. A shorter version of this review ran in the Wall Street Journal on April 1, 2014.

On the Margin

a book review by Michael Shermer

Of all the characters I’ve met in a quarter century spent researching the margins of science and society, there has never been anyone quite as enigmatic as David Irving, the British raconteur and historical revisionist of all things World War II, including and especially Hitler’s role in the Holocaust, which may or may not have happened, but if it did the Führer didn’t know about it, or if he did he couldn’t do anything to stop it. What about Hitler’s notorious anti-Semitism and his declaration of war against the Jews?, I once asked him. “Without Hitler, the State of Israel probably would not exist today so to that extent he was probably the Jews’ greatest friend.” Right. This from the man who once sued a historian for calling him a Holocaust denier, but then claimed, “More women died in the back seat of Edward Kennedy’s car at Chappaquiddick than ever died in a gas chamber at Auschwitz.” Irving lost his case in court, no doubt harmed when he slipped and referred to the Judge not as “Your Honor” but as “Mein Führer.” That might explain another one-liner that I’m sure I’m not the only person he’s told after shaking hands: “This hand has shaken more hands that shook Hitler’s hand than anyone else in the world.”

Irving is one of a pantheon of unconventional characters featured in Will Storr’s The Unpersuadables. Storr’s style is to get close to his subjects by spending enough time with them so that they let down their guard and tell him what they’re really thinking. For example, Storr joined Irving on a week-long tour of Nazi concentration camps, which he narrates in an engaging first-person style that takes the reader right into the gas chamber at Majdanek where Irving announces to his group and anyone else in ear-shot, “This is a mock-up of a gas chamber. Those cylinders are carbon dioxide not carbon monoxide. A typical Polish botch job. There are handles on the inside of these doors,” suggesting that the prisoners could have just let themselves out.

Storr’s purpose is to understand more than it is to debunk, but he gives his readers enough information to test the verisimilitude of his characters claims. For example, he examined those door hinges more closely to find that “there were bolts on the outside, two of them, huge ones, each attached to clasps that would have locked the door closed over airtight seals.” Storr adds that Irving “saw the handle and he used it to angrily damn the manifest truth. He saw the handle. What happened in his mind when he saw the bolts?” Was Irving, Storr wonders rhetorically, “a liar or deluded? Evil or mistaken?” Storr finds his answer in a cognitive process called the confirmation bias, where we look for and find confirming evidence for our beliefs and ignore or rationalize away disconfirming evidence. We all do this. We remember in great detail stories and studies that support our political preferences, forgetting all counter examples. We tend to befriend people who think like us and so reinforce our beliefs. It’s a cognitive bias not restricted to the unpersuadables, but when you’re dealing with sensitive topics like the Holocaust the bias is especially noticeable.

The beliefs that drive the confirmation bias in the first place come from a deeper place. “Follow the sacredness,” the psychologist Jonathan Haidt told Storr. “Find out what people believe to be sacred, and when you look around there you will find rampant irrationality.”

In his chapter on the world’s most prominent climate-change skeptic, Christopher Monckton, Storr finds the sacredness in Monckton’s bemoaning of Britain’s loss of empire: “I felt infinite sadness. And nostalgia,” he told Storr in reference to his boyhood prep school. “When I was at Harrow we had a wonderful school song which said ‘From Harrow school to rise and rule.’” Monckton, Storr discovers, is the selfproclaimed “liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Broderers, this Officer of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, this Knight of Honour and Devotion of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta, this former policy adviser to Margaret Thatcher,” who is also “the first son of Major General Gilbert Monckton, 2nd Viscount Monckton of Brenchley and Marianna, Dame of Malta.” No wonder he believed that his education “was very much that you are going to be the rulers of the world and the masters of the universe and, therefore, you need to know how to do it.”

What does this have do with carbon emissions and climate change that Monckton has become famous for denying? (Recall his massive 2006 ad campaign to bait Al Gore into a debate.) Hitler could not destroy Britain from without, but the labour party and its welfare state is dismantling it from within by, in part, concocting a phony crisis—global warming —and then grabbing the reins of power. Why? “To shut down the economies of the West,” Monckton tells Storr. “I’ve been told that the left, the KGB, realized that energy was the soft underbelly of the West. They used twin attacks via the working classes and the environment movement. They thought, ‘That’s how we destroy the economies of the West’.”

The subtle brilliance of The Unpersuadables is Storr’s style of letting his subjects hang themselves by their own words. Storr notes that in 1987, for example, Monckton hatched a plan that he published in the American Spectator on how to stop AIDS from spreading: “screen the entire population regularly and quarantine all carriers of the disease for life. …Strict controls would be needed at all borders. Visitors would be required to take blood-tests at the port of entry and would be quarantined in the immigration building until the tests had proved negative.” This, Storr adds, comes from the man who accuses the left of totalitarianism and its drive for “absolute control over every detail.”

Storr’s other subjects include ESP researcher Rupert Sheldrake, the late Harvard alien abductee chronicler John Mack, creationist John Mackay, past-life regressionist Vered Kilstein, and other self-proclaimed heretics, all of whom have a story of “crisis, struggle, resolution.” This narrative arc, says Storr, is the substrate that binds these disparate characters and their fringe beliefs together. They are “Hero- Makers” in their minds, fighting the “Demon-Makers” out to deceive or destroy us. Thus, their battles against the establishment are not just turf wars over some point of arcana, but epic crusades in the name of their highest ideals, however out of sync they are with the world. ![]()

Our Next Science Lecture

Humble Before The Void: Western Science Meets Tibetan Buddhism

with Dr. Chris Impey

Sun., May 18, 2014 at 2 pm

Baxter Lecture Hall

SURPRISE, DELIGHT, AND UNBRIDLED MIRTH are not commonly encountered in the science classroom. But in the foothills of the Himalaya, at a program to teach cosmology to Buddhist monks by the University of Arizona astronomer Chris Impey, they were daily occurrences. Working with this unique audience spurred new ways of thinking about the universe and the art of teaching. This talk takes listeners on an adventure at the nexus of science, religion, philosophy, and culture. Dr. Impey studies quasars and distant galaxies and is the author of How it Began, How it Ends, and The Living Cosmos, and has won 11 teaching awards. Order Humble Before The Void from Amazon.

TICKETS are first come, first served at the door. Seating is limited. $10 for Skeptics Society members and the JPL/Caltech community, $15 for nonmembers. Your admission fee is a donation that pays for our lecture expenses.

Followed by: a screening of the documentary film Particle Fever

“Mind Blowing”

— The New York Times

Particle Fever follows the inside story of six brilliant scientists seeking to unravel the mysteries of the universe, documenting the successes and setbacks in the planet’s most significant and inspiring scientific breakthrough

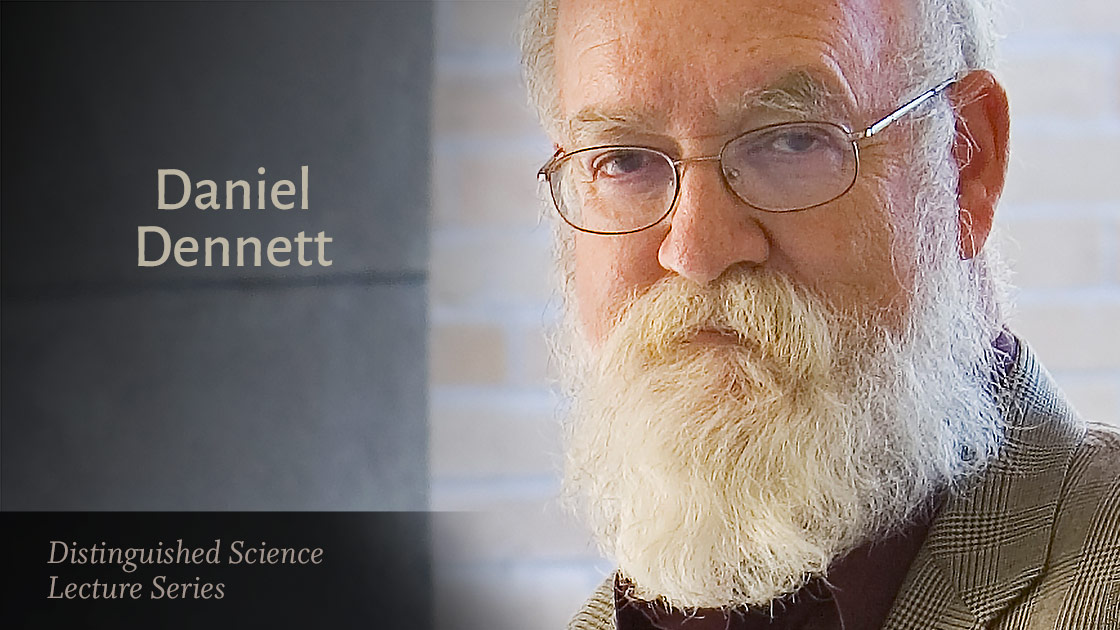

DISTINGUISHED SCIENCE LECTURE

Dr. Daniel Dennett — Freedom Evolves: Free Will, Determinism, and Evolution

Can there be freedom and free will in a deterministic world? Renowned philosopher and public intellectual, Dr. Dennett, drawing on evolutionary biology, cognitive neuroscience, economics and philosophy, demonstrates that free will exists in a deterministic world for humans only, and that this gives us morality, meaning, and moral culpability. Weaving a richly detailed narrative, Dennett explains in a series of strikingly original arguments that far from being an enemy of traditional explorations of freedom, morality, and meaning, the evolutionary perspective can be an indispensable ally. In Freedom Evolves, Dennett seeks to place ethics on the foundation it deserves: a realistic, naturalistic, potentially unified vision of our place in nature.

You play a vital part in our commitment to promote science and reason. If you enjoyed this Distinguished Science Lecture, please show your support by making a donation.