In this week’s eSkeptic:

May 29–31, 2015 / Save the Dates!

Announcing the 2015 Skeptics Society Conference, at Caltech’s Beckman Auditorium

Save the dates for our upcoming conference in May, hosted by Michael Shermer at Caltech’s Beckman Auditorium.

Topics

The future of the universe, the solar system, and the earth and its resources; the fate of civilizations and the nation-state; changing economic systems; the expanding moral sphere and progress or regress in morality; what language humans will speak; what race (if any) humans will be; the changing nature of gender roles; the future of religion, conflicts, and wars; how we can (or if we should) colonize the solar system and galaxy; and how humanity can become a Type I, Type II, or even a Type III civilization.

Confirmed speakers

Richard Dawkins, Jared Diamond, Lawrence Krauss, Esther Dyson, John McWhorter, Ian Morris, Carol Tavris, Greg Benford, David Brin, and Donald Prothero.

Entertainment

Close-up magic; Art Benjamin—the mathemagician and lightning calculator; and musical virtuoso Frankie Moreno—pianist and performer prodigy turned Las Vegas headliner sensation.

Basic Itinerary

Friday night dinner with the speakers and special guests. Saturday lectures and evening show. Sunday geology tour to see California’s faults OR a trip to Mt. Wilson to see where Edwin Hubble discovered the expanding universe.

Registration

See the 2015 conference web page for more details and registration information to come. Save the dates for this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see and hear some of today’s greatest minds and most talented performers.

Don’t miss BILL NYE, the Science Guy

in conversation with Michael Shermer, discussing Bill’s new book: Undeniable: Evolution and the Science of Creation

Sun., Jan. 25, 2015 at 2 pm

Beckman Auditorium

SPARKED BY A CONTROVERSIAL DEBATE in February 2014, Bill Nye has set off on an energetic campaign to spread awareness of evolution and the powerful way it shapes our lives. In Undeniable: Evolution and the Science of Creation, he explains why race does not really exist; evaluates the true promise and peril of genetically modified food; reveals how new species are born, in a dog kennel and in a London subway; takes a stroll through 4.5 billion years of time; and explores the new search for alien life, including aliens right here on Earth. With infectious enthusiasm, Bill Nye shows that evolution is much more than a rebuttal to creationism; it is an essential way to understand how nature works—and to change the world. Don’t miss this enlightening “In Conversation” with Bill Nye, hosted by Michael Shermer.

A book signing will follow the lecture. We will have copies of the book, Undeniable: Evolution and the Science of Creation, available for purchase. Can’t attend the lecture? Order Undeniable from Amazon.

Ticket Information

Tickets are $15 for Skeptics Society members/Caltech/JPL community; $20 for general public; $5 for Caltech students. Tickets may be purchased in advance through the Caltech ticket office in 101 Winnett, at the door, by calling at 626-395-4652 between 9am–4pm Monday through Friday (Do not leave a message.), or online using the link below. Ordering tickets ahead of time is strongly recommended.

Weekly Highlights

ABOVE: A screenshot from January 12, 2015 of the Charlie Hebdo website. The Je suis Charlie (“I am Charlie”) slogan has quickly became an endorsement of freedom of speech and press, with the hashtag #jesuischarlie having reached about 5 million tweets since last week’s shooting, when two gunmen opened fire in the Paris headquarters of Charlie Hebdo, killing twelve.

Some might characterize the faith-inspired murder of satirical cartoonists as shocking. But the prospect of violent reprisal for religious criticism was hardly inconceivable to the now-deceased artists of Charlie Hebdo. In this week’s eSkeptic, Kenneth Krause describes potential relationships between religion and violence, and questions whether these murders would seem possible in the absence of religious devotion to an allegedly all-powerful god.

Kenneth W. Krause is a contributing editor and “Science Watch” columnist for the Skeptical Inquirer and a regular contributor to Skeptic magazine.

Charlie Hebdo: Why Islam, Again?

by Kenneth W. Krause

Some might characterize the faith-inspired murder of satirical cartoonists as shocking. But the prospect of violent reprisal for religious criticism was hardly inconceivable to the now-deceased artists of Charlie Hebdo. In 2011, for example the magazine’s same Parisian offices were firebombed for publishing an issue purportedly guest-edited by the Prophet Muhammad.

Nor was last week’s three-day massacre of 17 people a colossal surprise to me. It might have been, I suppose, if such attacks typically derived merely from the dysfunctional minds of irreligious psychopaths or the maniacal excesses of religious “extremists,” as most commentators tend to describe them.

But, as the perpetrators themselves all-too proudly confess, these are acts firmly grounded in religious text and tradition. Of course, it can be difficult to determine whether a violent act occurs because of religious belief. It is insufficient to simply note, as some critics of religion often do, that the Bible prescribes death for a variety of objectively mundane offenses, including adultery (Leviticus 20:10) and taking the Lord’s name in vain (Leviticus 24:16). And to merely remind, for example, that Deuteronomy 13:7–11 commands the devoted to stone to death all who attempt to “divert you from Yahweh your God,” or that Qur’an 9:73 instructs prophets of Islam to “make war” on unbelievers, provides precious little evidence upon which to base an indictment of religious conviction.

Sam Harris’s vague declaration, “As man believes, so will he act,” seems entirely plausible, of course, but also highly presumptive given the fact that people are known to frequently hold two or more conflicting beliefs at once.1 Nor can we casually assume that every suicide bomber or terrorist has taken inspiration from holy authority—even if he or she is religious.

But there is substantial merit in Harris’s criticism of religionists who, regardless of the circumstances, “tend to argue that it is not faith itself but man’s baser nature that inspires such violence.” First, there can exist more than one sine qua non, or cause-in-fact for any outcome, especially in the psychologically knotty context of human aggression. Furthermore, when aggressors declare religious inspiration, as the Charlie Hebdo murderers did, we should accept them at their word.

A More Methodical Approach

But to more astutely characterize the relationship between religion and violence, and to distinguish between differentially aggressive traditions, we should apply a more disciplined method. Cultural anthropologist David Eller proposes a comprehensive model of violence consisting of five contributing dimensions or conditions that, together, predict the source’s propensity to expand both the scope and scale of hostility.2 These dimensions include group integration, identity, institutions, interests, and ideology.

Eller applies his model to religion as follows: First, religion is clearly a group venture featuring “exclusionary membership,” “collective ideas,” and “the leadership principle, with attendant expectations of conformity if not strict obedience”—often to superhuman authorities deserving of special deference. Second, sacred traditions offer both personal and collective identities to their adherents that stimulate moods, motivations, and “most critically, actions.”

Next, most faiths provide institutions, perhaps involving creeds, codes of conduct, rituals, and hierarchical offices which at some point, according to Eller, can render the religion indistinguishable from government. Fourth, all religions aspire to fulfill certain interests. Most crucially, they seek to preserve and perpetuate the group along with its doctrines and behavioral norms. The attainment of ultimate good or evil (heaven or hell, for example), the discouragement or punishment of “dissent or deviance,” proselytization and conversion, and opposition to non-believers might be included as well.

Finally, “religion may be the ultimate ideology,” the author avers, “since its framework is so totally external (i.e., supernaturally ordained or given), its rules and standards so obligatory, its bonds so unbreakable, and its legitimation so absolute.” For Eller, the “supernatural premise” is critical:

This provides the most effective possible legitimation for what we are ordered or ordained to do: it makes the group, its identity, its institutions, its interests, and its particular ideology good and right … by definition. Therefore, if it is in the identity or the institutions or the interests or the ideology of a religion to be violent, that too is good and right, even righteous.

Arguably, Eller concludes, “no other social force observed in history can meet those conditions as well as religion.” And when a given tradition satisfies multiple conditions, “violence becomes not only likely but comparatively minor in the light of greater religious truths.”

Confronting the question at hand, then, I propose a somewhat familiar, though perhaps distinctively limited two-part hypothesis describing potential relationships between religion and aggression. First, I do not contend that religion is ever the sole, original, or even primary cause of bellicosity. Such might be the case in any given instance, but for the purpose of determining generally whether faith plays a meaningful role in violence, we need only ask whether the religion is a sine qua non of the conflict.

Second, although all religions can and often do stimulate a variety of both positive and negative behaviors, clearly not all faiths are identical in their inherent inclination toward hostility. Indeed, there should be little question that Judaism, Christianity, and Islam satisfied each of Eller’s conditions. Accordingly, I suggest that the Abrahamic monotheisms are either uniquely adapted to the task or otherwise especially capable of inspiring violence from both their followers and non-followers.

Monotheism Conceptually

Eller denies that all religion is “inherently” violent. Nonetheless, he recognizes monotheism’s tendency toward a dualistic, good versus evil, attitude that not only “builds conflict into the very fabric of the cosmic system” by crafting two “irrevocably antagonistic” domains “with the ever-present potential for actual conflict and violence,” but also “breeds and demands a fervor of belief that makes persecution seem necessary and valuable.”

Baylor University anthropologist Rodney Stark agrees. Committed to a “doctrine of exclusive religious truth,” he writes, particularistic traditions “always contain the potential for dangerous conflicts because theological disagreements seem inevitable.” Innovative heresy naturally arises from the religious person’s desire to comprehend scripture thought to be inspired by the all-powerful and “one true god.” As such, Stark finds, “the decisive factor governing religious hatred and conflict is whether, and to what degree, religious disagreement—pluralism, if you will—is tolerated.”3

Religious author Jonathan Kirsch compared the relative bellicosity of polytheistic and monotheistic traditions this way:

[F]atefully, monotheism turned out to inspire a ferocity and even a fanaticism that are mostly absent from polytheism. At the heart of polytheism is an open-minded and easygoing approach to religious belief and practice, a willingness to entertain the idea that there are many gods and many ways to worship them. At the heart of monotheism, by contrast, is the sure conviction that only a single god exists, a tendency to regard one’s own rituals and practices as the only proper way to worship the one true god.4

Religious scholar Edward Meltzer adds that for the monotheist, “all divine volition must have one source, and this entails the attribution of violent and vengeful actions to one and the same deity and makes them an indelible part of the divine persona.” Meanwhile, polytheists “have the flexibility of compartmentalizing the divine” and to “place responsibility for … repugnant actions on certain deities, and thus to marginalize them.”5

For Kirsch, the Biblical tale of the golden calf reveals an exceptional belligerence in the faiths of Abraham. After convincing a pitiless and indiscriminate Yahweh not to obliterate every Israelite for worshiping the false idol, Moses nonetheless organizes a “death squad” to murder the 3,000 men and women (to “slay brother, neighbor, and kin,” according to Exodus 32:27) who actually betrayed their strangely jealous god.

In the Pentateuch and elsewhere, Kirsch elaborates, “the Bible can be read as a bitter song of despair as sung by the disappointed prophets of Yahweh who tried but failed to call their fellow Israelites to worship of the True God.” “Fatefully,” Kirsch notes, the prophets—like their wrathful deity—“are roused to a fierce, relentless and punishing anger toward any man or woman who they find to be insufficiently faithful.”

This ultimate and non-negotiable “exclusivism” of worship and belief, Kirsch concludes, comprises the “core value of monotheism.” And “the most militant monotheists—Jews, Christians and Muslims alike—embrace the belief that God demands the blood of the nonbeliever” because the foulest of sins is not lust, greed, rape, or even murder, but “rather the offering of worship to gods and goddesses other than the True God.”

Indeed, as Biblical archeologist Eric Cline observed a decade ago, Jerusalem alone has suffered 118 separate conflicts in the past four millennia. It has been “completely destroyed twice, besieged twenty-three times, attacked an additional fifty-two times, and captured and recaptured forty-four times.” The city has endured twenty revolts and “at least five separate periods of violent terrorist attacks during the past century.”6

Modern Islam

Sam Harris believes we are at war with Islam. “It is not merely that we are at war with an otherwise peaceful religion that has been ‘hijacked’ by extremists,” he argues. “We are at war with precisely the vision of life that is prescribed to all Muslims in the Koran, and further elaborated in the literature of the hadith.” “A future in which Islam and the West do not stand on the brink of mutual annihilation,” Harris portends, “is a future in which most Muslims have learned to ignore most of their canon, just as most Christians have learned to do.”7

Is it unfair of Harris to target Islam when Western history is saturated with Christian bloodshed? Pope Innocent III’s 13th-century crusade against the French Cathars, for example, may have ended a million lives. The French Religious Wars of the 16th-century between Catholics and Protestant Huguenots left around three million slain, and the 17th-century Thirty Years War waged by French and Spanish Catholics against Protestant Germans and Scandinavians annihilated perhaps 7.5 million.

Islamic scholar and apostate, Ibn Warraq, doesn’t think so. Westerners tend to mistakenly differentiate between Islam and “Islamic fundamentalism,” he explains. The two are actually one in the same, he says, because Islamic cultures continue to read their Qur’an and hadith literally. Such societies will remain hostile to democratic ideals, Warraq advises, until they permit a “rigorous self-criticism that eschews comforting delusions of a…Golden Age of total Muslim victory in all spheres; the separation of religion and state; and secularism.”8

Likely entailed in this hypothetical transformation would be a religious schism the magnitude of which would resemble the Christian Reformation in its tendency to wrest scriptural control and interpretation from the clutch of religious and political elites and into the hands of commoners. Only then can a meaningful Enlightenment toward secularism follow. And as author Lee Harris has opined, “with the advent of universal secular education, undertaken by the state, the goal was to create whole populations that refrained from solving their conflicts through an appeal to violence.”9

In the contemporary West, Rodney Stark concurs, “religious wars seldom involve bloodshed, being primarily conducted in the courts and legislative bodies.”10 In the United States, for example, anti-abortion terrorism might be the only exception, and even that has become rare. But such is clearly not the case in many Muslim nations, where religious battles continue and are now “mainly fought by civilian volunteers.”

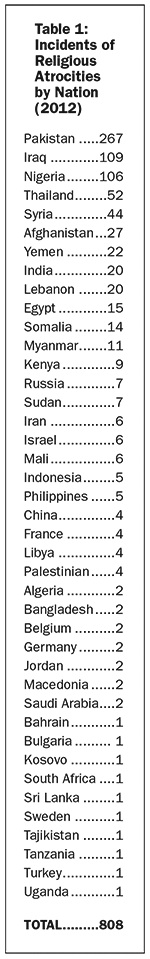

In fact, data recently collected by Stark appears to support Sam Harris’s critique rather robustly. Consulting a variety of worldwide sources, Stark assembled a list of all religious atrocities that occurred during 2012.11 In order to qualify, each attack had to be religiously motivated and result in at least one fatality. Attacks committed by government forces were excluded. In the process, Stark’s team “became deeply concerned that nearly all of the cases we were finding involved Muslim attackers, and the rest were Buddhists.” In the end, they discovered only three Christian assaults—all “reprisals for Muslim attacks on Christians.”

In all, 808 religiously motivated homicides were found in the reports. A total of 5,026 persons died—3,774 Muslims, 1,045 Christians, 110 Buddhists, 23 Jews, 21 Hindus, and 53 seculars. Most were killed with explosives or firearms but, disturbingly, 24 percent died from beatings or torture perpetrated not by deranged individuals, but rather by “organized groups.” In fact, Stark details, many reports “tell of gouged out eyes, of tongues torn out and testicles crushed, of rapes and beatings, all done prior to victims being burned to death, stoned, or slowly cut to pieces.”

As Table 1 shows, present-day religious terrorism almost always occurs within Islam: 70 percent of the atrocities took place in Muslim countries, and 75 percent of the victims were Muslims slaughtered by other Muslims, often the result of majority Sunni killing Shi’ah (the majority only in Iran and Iraq). Pakistan (80 percent Sunni) ranked first in 2012, likely due to its chronically weak central government and the contributions of al-Qaeda and the Taliban.

Christians accounted for 20 percent (159) of all documented victims. Eleven percent of those (17) were killed in Pakistan, but nearly half (79) were slain in Nigeria, often by Muslim members of Boko Haram, often translated from the Hausa language as “Western education is forbidden.” Formally known as the Congregation and People of Tradition for Proselytism and Jihad, Boko Haram was founded in 2002 to impose Muslim rule on 170 million Nigerians, nearly half of which are Christian. Some estimate that Boko Haram jihadists—funded in part by Saudi Arabia—have murdered more than 10,000 people in the last decade.

Such attacks are indisputably perpetrated by few among many Muslims. But whether the Muslim world condemns religious extremism, even religious violence, is another question. According to Stark, “it is incorrect to claim that the support of religious terrorism in the Islamic world is only among small, unrepresentative cells of extremists.” In fact, recent polling data tends to demonstrate “more widespread public support than many have believed.”

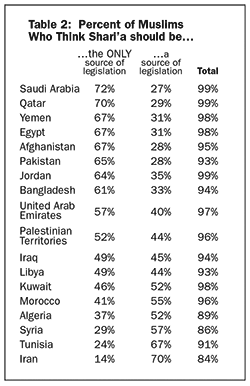

Shari’a, the religious law and moral code of Islam, is considered infallible because it derives from the Qur’an, tracks the examples of Muhammad, and is thought to have been given by Allah. It controls everything from politics and economics to prayer, sex, hygiene, and diet. The expressed goal of all militant Muslim groups, Stark argues, is to establish Shari’a everywhere in the world.

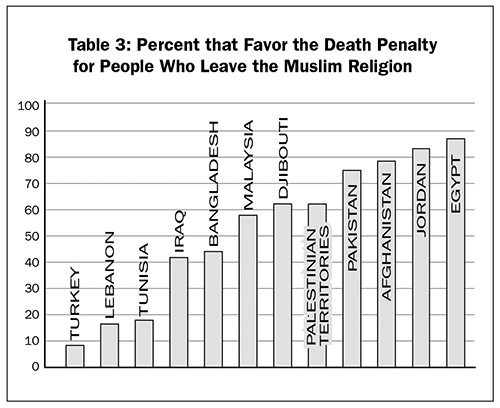

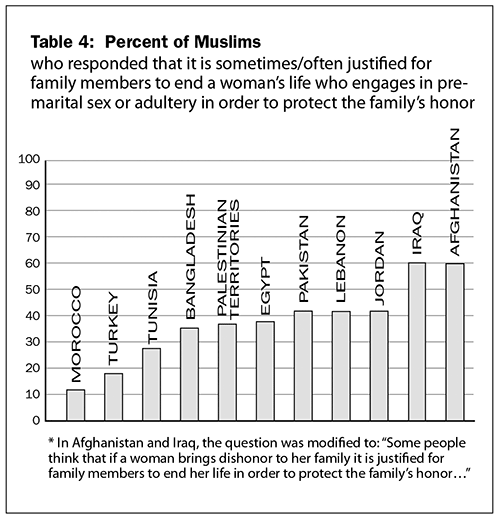

Gallup World Polls from 2007 and 2008 show that nearly all Muslims in Muslim countries want Shari’a to play some role in government.12 As Table 2 illustrates, the degree of desired implementation varies from nation to nation. Strikingly, however, a clear majority in 10 Muslim countries—and a two-thirds supermajority in five—want Shari’a to be the exclusive source of legislation. In 2013, the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life asked citizens in 12 Islamic nations whether they supported the death penalty for apostasy.13 Their responses are reflected in Table 3. Table 4 shows the percentage of Muslims in 11 countries who believe it is often or sometimes justified to kill a woman for adultery or premarital sex in order to protect her family’s honor. Thankfully, only in Pakistan and Iraq do a majority (60 percent) agree. But in all other Muslim nations polled, a substantial minority—including 41 percent in Jordan, Lebanon, and Pakistan—appear to approve of these horrific murders as well as their governments’ documented reluctance to prosecute them.

Conclusion

Islam is not universally violent, of course. The same polls, for example, show that few British and German Muslims and only five percent of French Muslims agree that honor killing is morally acceptable. But the data from Islamic nations tends first, to support the proposition that Abrahamic monotheism is uniquely adapted to inspire violence, and second, to demonstrate that the belief in one god continues to fulfill this exceptionally vicious legacy. It is no accident, for example, that nearly all Muslims in these countries are particularists, believing that “Islam is the one true faith leading to eternal life.”14

In conclusion, none of this would seem possible in the absence of religious devotion to an allegedly all-powerful god. ![]()

References

- Harris, Sam. 2005. The End of Faith. NY: W.W. Norton.

- Eller, Jack David. 2010. Cruel Creeds, Virtuous Violence: Religious Violence across Culture and History. NY: Prometheus.

- Stark, R. and K. Corcoran. 2014. Religious Hostility: A Global Assessment of Hatred and Terror. Waco, TX: ISR Books.

- Kirsch, J. 2004. God Against the Gods: The History of the War Between Monotheism and Polytheism. NY: Viking Compass.

- Meltzer, E. 2004. “Violence, Prejudice, and Religion: A Reflection on the Ancient Near East,” in The Destructive Power of Religion: Violence in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (Volume 2: Religion, Psychology, and Violence), ed. J. Harold Ellens. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Cline, E.H. 2004. Jerusalem Besieged: From Ancient Canaan to Modern Israel. U. of Mich. Press.

- Harris, The End of Faith.

- Warraq, Ibn. 2003. Why I Am Not a Muslim. Amherst, NY: Prometheus.

- Harris, L. 2007. The Suicide of Reason: Radical Islam’s Threat to the West. NY: Basic Books.

- Stark and Corcoran, Religious Hostility.

- Stark’s sources included thereligionofpeace.com, the Political Instability Task Force Worldwide Atrocities Data Set, Tel Aviv University’s annual report on worldwide anti-Semitic incidents, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom’s annual report for 2013, and the U.S. State Department’s International Freedom Report, 2013.

- The Gallup World Poll studies have surveyed at least 1000 adults in each of 160 countries (having about 97 percent of the world’s population) every year since 2005.

- The World’s Muslims: Religion, Politics and Society. 2013. http://pewrsr.ch/19aHxGF (posted April 30, 2013) and http://pewrsr.ch/1zg1Yxh

- Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, The World’s Muslims: Religion Politics and Society. (Washington, DC, 2013).