![Ray Hyman demonstrates Uri Gueller's spoon bending feats at CFI lecture. June 17, 2012 Costa Mesa, CA (photo by Sgerbic (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.skeptic.com/eskeptic/2015/images/15-05-13/Ray_Hyman_Spoon_Bending_CFI_by_Sgerbic.jpg)

Ray Hyman demonstrates Uri Gueller’s spoon bending feats at CFI lecture. June 17, 2012 Costa Mesa, CA, by Sgerbic (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

About this week’s eSkeptic

In this week’s eSkeptic, we present a skeptical classic: an interview with a co-founder of modern skepticism: Ray Hyman. This interview first appeared in Skeptic magazine 6.2, back in 1998.

The Truth is Out There

and Ray Hyman Wants to Find it

by Michael Shermer

Three names dominate the early history of the modern skeptical movement: James Randi, Martin Gardner, and Ray Hyman. Perhaps less wellknown by the general public than the first two, Ray Hyman is the only one of the group with formal training in the experimental sciences (although the other two have more than made up for it with hands-on real world experience). That training has come in handy in Hyman’s dealings with pseudoscience and the paranormal, as he has continuously (from the 1950s on) conducted formal and informal investigations of all manner of extraordinary claims, from Uri Geller’s ability to bend spoons to the CIA’s remote viewing experiments. When the Department of Defense needed someone to investigate the Israeli spoon-bending psychic, they called Ray Hyman. When James Randi needs advice on statistical analysis, he often calls Ray Hyman. When Scientific American needed advice on experimental protocol to test a water dowser for their TV series Frontiers they called Ray Hyman. When the government needed an objective outsider to examine the data from the CIA’s remote viewing experiments, they called Ray Hyman. Hyman is meticulous in his research, careful in his analysis, and always thoughtful in dealing with claimants, many of whom it would be generous to call cranks and charlatans. But Hyman is more interested in how we all deceive ourselves than in how scam artists deceive the few us.

Ray Hyman turns 70 this year [86 as of the publication date of this eSkeptic], and with that he plans to retire from a long and productive academic career as an experimental psychologist. But this won’t slow his quest to find the truth about psi, the paranormal, and the psychology of belief, a quest which began when he was a young boy growing up as second of three children in Everett, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston. Hyman’s older brother was killed during World War II at Iwo Jima, and his younger sister is a recently retired college art instructor. His father was a native-born accountant and his mother was a dressmaker who immigrated from Russia. The only Jews in their neighborhood, Hyman’s parents fretted over “what the neighbors thought,” and for good reason in those less enlightened and tolerant days before WWII.

For the intellectually precocious Hyman, however, the religious impulse never clicked. “When I went to synagogue as a kid I’d come home and say, ‘This is a smelly place and the people there are crooks who come here and pretend they’re religious’. I never had a religious feeling.” The astute youngster began his data collection early by noting that “When I lived in Italy, the Catholic ceremonies were beautiful. I always felt I was missing something. I guess this could make people feel good, but I’ve never had any of that. I empathize with people who have, however.” He was bar mitzvahed at 13, but “that was the end of it. I didn’t understand what was going on and I could see the whole thing was a phony ritual.”

The product of a politically left-leaning home, Hyman was raised to worship Franklin Roosevelt. He observed “Uncle Joe” (Stalin) change from an ally and hero during the war against Hitler, to an arch enemy after the war. “This struck me as weird,” as did his father’s sudden loss of faith, which taught Hyman the power of belief systems: “I remember that when my brother got killed my father suddenly announced that he was an atheist. It was over, just like that. He had nothing more to do with religion of any kind.” The death of his brother also taught Hyman something about the psychology of anomalous experiences, and about probabilities. His brother landed on the beach at Normandy on D-day and survived. Later he was shipped to the Pacific, after which “I remember my mother had this dream that my brother was going to be killed and sure enough, next day or two we got the telegram. I told her, and I was only 16, ‘Look, you’ve been having that dream every night that he has been in the service!’ And practically everyone during the initial invasion of Iwo Jima was killed.”

Coupled to these youthful experiences was Hyman’s early interest in magic, and the lessons he learned from his first hero—Harry Houdini:

When I was in high school I went to every spiritualist seance I could find in the Boston area because I wanted to be like Houdini. I was going to expose all this stuff. The first thing I noticed was that I was the oddball there; it was mostly elderly women and a few elderly men…and me, this young kid! They accepted me, more or less, and I took some spiritualist development classes where they tried to teach us how to reach the spirit world. We were assigned a guiding spirit. I don’t know why, but all the spirits had American Indian names—one was Chief Looking Glass. After three or four sessions they were all doing it and pretty soon I was the only one not apparently seeing the spirits, so I finally dropped out.

It was his first official skeptical investigation that would lead to a lifelong quest to find the truth that he knew was out there…somewhere. I sat down with Ray at the January, 1998 “Gathering for Gardner Three” (G4G3), an eclectic collection of mathematicians, magicians, mentalists, game designers, scholars, scientists, and anyone interested in the varied intellectual products of clever minds, who gathered to pay tribute to their collective colleague and hero, Martin Gardner.

Skeptic: What sort of things did you discover about the world of spiritualism in those early experiences?

The article you are reading appeared in this issue of Skeptic magazine. Order the back issue.

Hyman: I’ll tell you a story. I was sitting in a general spiritmessage seance, performed as a come-on to get you into their private readings the next day. People put their “spirit messages” in a basket, and this old guy, blindfolded, pulled out the messages one by one, held them to his forehead, and pretended to read them. He was peeking down his nose under his blindfold and reading the message he had opened on the lectern while holding a substitute message to his forehead. Because he was older and his eyesight not so good, he was blatantly pushing the blindfold up and away from his eyes as he leaned forward to get a better view of the message. So I nudged the lady sitting beside me, but she was looking at the ceiling. She looked at me, looked around the room, then looked back up at the ceiling. I looked around the room and it dawned on me that none of these people were looking at this guy because they didn’t want to know it was a fake.

Related to this, every Wednesday night my father used to take me to professional wrestling matches at the Boston Garden, which he loved. Here I noticed that there was always a good guy and a bad guy, and I also wondered how these guys could still see when they gouged each other’s eyes out every week, and that there were all these different “world” champions (how many can you have?!). So it occurred to me that professional wrestling was also a fake. One time, just for fun, I began cheering for the villain, and this lady got up and came over and started swinging her purse and hitting me with it. After a while I tried to talk my father out of it but he didn’t want to hear it.

Skeptic: They willingly suspended their disbelief?

Hyman: Right. People don’t want to know the truth behind the façade. Decades ago this professor at Oregon State University put on this conference on confidence games and cons of all kinds (he called it “The Big CONference”). Jerry Andrus and I were there, and the Oregon State newspaper ran my picture with the headline HE TAKES AWAY SANTA CLAUS. I’ll always remember that because it is a good lesson on how people react to skeptics. Skepticism is always seen as negative, where people think we are are taking something away without putting anything back.

It reminds me of an experience I had as a professor teaching a course on pseudopsychology in 1970, just before Uri Geller came on the scene. At the end of the course a student came to me and said “You know, Professor Hyman, as a result of taking your course I now realize how I’ve been fooling myself. And I see how others fool themselves as well. But, you know, I wish I had never taken your class. I hate your guts.”

Skeptic: He was serious?

Hyman: Oh, yes, this was no joke. I realized again that people just don’t want to know. Many years later, for example, a wellknown magician came up to me and said he needed to talk to me. Paul was a very active skeptic, and at that time he was dating this woman who gave “readings” to people in Hollywood, but presented them as real. And he said to me, “You know, Ray, there is an ethical issue here. Do I have the right to try to convince them that they are being fooled? Is this fulfilling some purpose for them and I’m just taking it away?” That is a real issue for skeptics.

Skeptic: What is your answer to this ethical question?

Hyman: My answer explains why I’m always called the softy of the skeptical movement. Randi’s approach is to get out there and confront them. I’m the nonconfrontational skeptic. I’m the good cop, he’s the bad cop. I’m in the ivory tower, Randi’s out there in the trenches. I can afford to be flexible. He can’t. Out there you can’t give them any wiggle room. My approach is that I don’t want to shove anything down anyone’s throat. But if they want to know, I’m willing to tell them about it.

Skeptic: You’re not the proselytizing type?

Hyman: No. In fact, one of the main things I have against almost every religion is the proselytizing aspect of it. I tell them, “Look, if it is so good why do you need to sell me God?”

Skeptic: You’ve been interested in magic all your life. What is the connection between magic and skepticism for you?

Hyman: It is through magic that I got into skepticism. Most magicians are skeptics (unlike most mentalists, who tend to believe in the paranormal). So I always took it for granted as a magician that I was also a skeptic.

I did my first magic show when I was seven years old. My father gave me a magic kit that I took to school for “show and tell,” and the teacher thought it was good enough that she asked me to do it for a PTA meeting. So I did that and they gave me $5, which in those days was a lot of money. So I had a business card made and the printer called me “The Merry Mystic,” because we lived on the Mystic River at the time, and he put a rabbit and a hat on the card, so I was now a real magician. And I bought a top hat and the next week the library hired me for a story hour show, and it took off from there. I started getting shows regularly and hanging out at magic shops, and really learned the craft. And I did shows for money all the way through my last year of college at Boston University.

Skeptic: Is this how you got into palm reading?

Hyman: Well, early on in my magic career I realized I could make more money doing mentalism than magic. People would pay me at least three times more for a mentalism show than for a magic show. The reason is that they assumed the magic tricks were tricks, but that mentalism was real. I would always come out and tell them at the beginning, “Look, I am going to do something here but I’m not claiming any special powers, although I have practiced this a lot, so you decide what is going on here.” And with this I never got challenged. I was always considered a mind reader. After every show, and I was just a little kid, these women would take me aside and tell me about their personal lives and I was blushing, and they wanted a private reading with me. I realized that I only needed to get one little fact about them and they would attribute all kinds of powers to me.

Skeptic: How have you used this to better your understanding of the psychology of deception?

Hyman: When I was studying psychology, the “psychology of deception” was really the “psychology of conjuring.” The assumption was that if you understand how conjuring works you understand deception. But as I worked on an article about this, I realized that this cannot be the case because there is a big difference between conjuring and deception in everyday life. In conjuring, the last thing you want is for people not to realize they are being deceived. When I’m up there on stage, if people do not realize they have been deceived then I have failed as a magician. But in real life scam artists try desperately not to let the person know they are being deceived. Good con games take people over and over.

On the flip side, if people know they are being deceived and you can still deceive them through magic, that is a powerful lesson.

Skeptic: What did you learn about yourself in doing magic and mentalism?

Hyman: Going back in time, I did palm readings for years, and for awhile I had become a gung ho believer. I started as a skeptic but as I added things to my repertoire I became a believer. I couldn’t travel as a young magician so I was forced to play at the same places and had to come up with new things for them. This is when I took up palm reading. I watched people in the carnies and got to know them and picked up a lot of things from them. I didn’t want to do sword swallowing or anything like that, but with palm reading you could tell people all sorts of detailed things about themselves, like when they had a heart attack, at what age they were when they had a problem with their head, and so on.

By high school, even though I was a skeptic about most things, I believed in palm reading because it seemed plausible to me since the palm is physically connected with the body.

Skeptic: How did this tie in with your studies at Boston University? Were you a psychology major?

Hyman: Actually I was a journalism major. This was 1946 and out of a high school class of about a thousand, less than 20 of us went to college. I didn’t know what to major in, but my guidance counselor gave me a vocational test and he told me I should be a journalist. In my second year in college they gave me an assignment to interview a reporter, which I did, but this guy told me that the last thing you want to do to become a reporter is to take journalism classes! So I switched to psychology.

I distinctly remember an incident at Boston University—one of those you always remember—when the psychology department chair called me into his office one day, closed the door, sat me down, and proceeded to dress me down for doing palm reading, for taking people’s money under false pretenses, that there was nothing to this paranormal stuff and so on. I sat there listening to him and after he calmed down I said, “would you like me to read your palm?” So he stuck his hand out and I did a reading on him. Then I left. Two weeks later he called me back into his office, shut the door, sat me down, stuck his hand out, and said “tell me more!” This really showed me how powerful this stuff can be.

And in another one of those unforgettable incidents, the late Stanley Jaks convinced me to do a palm reading on someone and tell them the exact opposite of what I would normally say. So I did this. If I thought I saw in this woman’s palm that she had heart trouble at age 5, for example, I said, “well, you have a very strong heart,” that sort of thing. In this particular case, though, it was really spooky, because she just sat there poker faced. Usually I get a lot of feedback from the subject. In fact, I depend on the feedback, and this woman was giving me nothing. It was weird. I thought I bombed. But it turns out the reason she was so quiet was because she was stunned. She told me it was the most impressive reading she had ever had. So I did this with a couple more clients, and I suddenly realized that whatever was going on had nothing to do with what I said but with the presentation itself.

This was one of the reasons I went into psychology—I wanted to find out how it was that people, including myself, could be so easily deceived. In fact, this is one of the reasons why I am not as confrontational as Randi, because I actually see that “but there for the grace of God go I.”

Skeptic: You were a newly minted Ph.D. in 1953 from Johns Hopkins University. Throughout the next decade, what were some of the things you investigated that led to the founding of the modern skeptical movement?

Hyman: I was at Harvard for five years and there taught a class on con games, psychics, and so forth. Then I worked for three years in private industry, and after that I moved to the University of Oregon in 1961. I remember there was this lady in Russia who claimed she could read with her fingertips while blindfolded. An American woman who apparently could do the same thing was featured in Life magazine, and there was this American psychologist who was applying for grant money to study this woman in more detail. He wanted to figure out how she did it so he could train blind people to read this way. As a result, the National Institute of Health formed a committee to investigate her before they granted the funds, and they asked me to be on this committee.

So we went to Flint, Michigan, where this lady lived, and we watched the psychologist test her. The procedure was that he had her put her hands into these sleeves, and these went into a box where the reading material was, so there was no way she could be doing the nose peek technique. He would put inside the box three plastic chips, two of one color, one of a different color, and she could supposedly tell which one was the odd colored chip. He had previously tested her over thousands of trials and she was highly significantly—way above chance.

Well, when we met the psychologist he was eager to convince us he was using very strict controls, and he wanted us to help him make sure he was doing everything right. But we told him to do exactly what he had always done so we could see if there were any flaws in the procedure. But he added additional controls to convince us how careful he was. Well, it turned out that when he added these controls to his procedure the lady was only at chance level. He started making excuses, and so forth, so I told him to let me try it. I did and I got 100% right!

Skeptic: How did you do that?

Hyman: I learned in my research that it is very important when investigating these sorts of claims that you see everything that is done before the actual test. I had been there all day observing the psychologist, and I noticed that when he put in a new set of chips, he put the odd chip down first!

Skeptic: Obviously he didn’t realize he was doing this.

Hyman: No, and he was quite surprised that I was getting it right every time. So I explained what I was doing. We couldn’t be sure that she was consciously doing this—she might have unconsciously picked up the cue—but obviously something like this was going on.

Skeptic: Was this the start of the modern skeptical movement?

Hyman: Actually Uri Geller gets credit for that. In December, 1972, I was sitting in my office grading final exams when I got a phone call from Austin Kibler, a Colonel at the defense department, who worked in what was then called the Advanced Research Projects Agency of the Department of Defense, set up by President Kennedy. It was sort of the Buck Rogers part of the defense department dealing with futuristic technologies. Kibler had a Ph.D. in psychology so we knew each other a little, so he called and said “Ray, could you drop whatever you are doing and go on a mission for us to the Stanford Research Institute?” I said, “No, I’m grading exams.” But he insisted. “This is very important. There is this psychic down there. I know what you’re thinking, but this guy is not like any other psychic you have ever seen. He can do anything most psychics can do, but he can also bend metal with his mind.”

I sounded incredulous, so Kibler responded, “I don’t necessarily believe, but I’ve watched him myself and let me tell you what he did. In a room of scientists, not just psychologists (he meant so-called “real” scientists like physicists!), he asked to borrow a ring. He said ‘Don’t let me touch it.’ He didn’t touch the ring, which was placed in the middle of a table. He concentrated on it and the ring stood on end, split, and shaped itself into the letter S.” When I inquired more about it, it became clear that Kibler had not actually witnessed this himself, but had heard about it, and this was another lesson to me about what actually happens and what gets reported.

So Kibler said he wanted to send a parapsychologist and me down there, along with someone from the Defense Department, to test this guy named Geller. His reasoning was that if he was a fake I would detect it, but if he was real it would take a parapsychologist to see it! And he wanted me to go right away because he said Geller was very volatile, very temperamental, and that at any moment he might just get up and leave. So he begged me to go and the next day I found myself in the presence of Uri Geller. And, frankly, I wasn’t very impressed.

But before I went down I called Martin Gardner because I had never heard of Geller, as had no one else in this country. He had never heard of him either. So I called Amos Tversky in Israel, because Geller was from Israel. He knew of Geller and said as far as he knew Geller was a charlatan and a trickster. He gave me some background about how Geller had worked the night clubs and stuff like that. Now, at that time Geller wasn’t very good. He couldn’t bend keys as well as Randi could, for example, but he got much better with practice.

Skeptic: Did you figure out the ring effect?

Hyman: Yes! When I got there they introduced me to Geller, who had already met with the parapsychologists Russell Targ and Harold Putoff, and they showed me records of some experiments they had done with Geller over the past week. I kept asking them about this ring effect. Turns out it was not a finger ring, like I thought, but these brass rings, and they showed me one that was twisted into a figure 8, and they said they measured the amount of pressure it would take to bend it by hand. So I asked them why they were talking about him bending it by hand, when he supposedly bent it with his mind. And they said, “Oh, he can do it either way”! So I said, “did anyone actually see him bending this brass ring without touching it?”

It turns out that none of them had actually witnessed this great feat of mental metal bending. This whole story about how the brass ring got bent was from Geller himself! Geller told them he did this, and they just believed them. It was amazing. In fact, half the things I had heard about Geller, came from Geller himself, not from someone witnessing them. He would do something simple like bend a key using a standard magic effect, then say, “Oh, don’t count that, usually I can do this” and he would hold up a key twisted in a cork-screw fashion. Then the parapsychologists would tell everyone they saw him bend the key like a corkscrew, instead of what they actually saw. It was unbelievable!

Skeptic: So there was both deception and self-deception going on here.

Hyman: It was part of their own folklore. When they would tell a story you were never sure if they had seen it or only heard about it. And when you pressed them it usually turned out that no one had ever witnessed Geller doing these amazing feats.

One of my favorite places to find stories that turn into facts is in autobiographies. In the autobiography of the late psychologist Jean Piaget he tells the story that his earliest memory in life was being on a tram with his au pair who was taking him in a stroller to a park, as she usually did, when these men tried to kidnap him and she fought them off. Piaget said he always remembered that event. In his 60s or 70s, when he was writing his autobiography, he got a letter from this woman, saying how she felt guilty about something she wanted to get off her chest before she died. In this letter she told Piaget that this event never happened. It was a story she made up.

Skeptic: It was a false memory!

Hyman: Piaget explained that it had become part of the family lore and he had incorporated it as one of his memories.

Skeptic: It’s like when people see a magic trick they report seeing something very different from what actually happened.

Hyman: The parapsychologists had no doubt that Geller was for real, but it was obvious to me what was going on.

I then wrote a 13-page letter to Martin Gardner describing everything that happened with Geller (I always share these things with Martin because he is great at keeping confidences), but for some reason this 13-page letter became public. A mutual friend was visiting Martin and he saw the letter and, without telling Martin, photocopied it. Within a few weeks the letter had been distributed all over the place and it got back to SRI and they were threatening to sue me, and Time magazine wanted to quote it, and so forth. And in the midst of all this James Randi got hold of the letter, and that’s how he got involved with Geller.

The next month SRI took Geller to New York to visit Time magazine and other places to try to get some publicity for him, in order to generate research money from other sources because they knew my report for the Defense Department was not going to be positive. So Time contacted Randi who by now had my letter and brought him to New York as well. They disguised Randi as a reporter who was in the room when Geller was doing his routine. The Time article came out in February or March, 1973. This was the first big American story on Geller, called “The Magician and the Think Tank.” So Geller’s first exposure in this country was a complete debunking. And he took off from there!

Skeptic: It didn’t faze him at all.

Hyman: No, in fact, it launched him! About a year later Randi called me. We knew each other through Martin Gardner, but I didn’t know him personally (we were both disciples of Martin, of sorts), and at the time he was traveling with the rock group Alice Cooper playing the role of a mad doctor. They came to Portland and I got a call from Randi to come up to see the show, and that Alice Cooper wanted to meet me. So we got to talking and Randi said he really wanted to do something about Geller.

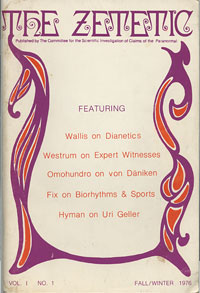

The 1976 founding issue of The Zetetic, now known as the Skeptical Inquirer.

As a result of this conversation, Randi, Martin Gardner and I formed an informal group called SIR—Scientists In Rationality—an obvious play on the Stanford Research Institute. We started holding informal meetings, like at Martin’s house, but none of us are administrators so there was a lot of talking but not much action. Then a sociologist at the University of Michigan named Marcello Truzzi heard about our group, and he contacted us and said he wanted to be a part of it. At that time Truzzi had a newsletter he called The Zetetic. It was simply a way of keeping academics informed about all this oddball stuff we were interested in, and he offered to do a newsletter for our group. So we took a look at a few issues and the three of us (Randi, Martin, and I) said “Yeah, why not?”

At about this time, Paul Kurtz was working at the American Humanist Association. He had managed to triple the circulation of The Humanist, and he put together the anti-astrology statement that got a lot of attention. One day he and Truzzi were talking on an elevator and decided to form a group. They gave it that horrible name I can never remember, and no one else can remember—The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal— which our enemies call the “PsiCops.” Then,Truzzi brought Randi, Martin and me into the group. They decided to have the first organizational meeting in 1976, in conjunction with a Humanist meeting that was already taking place at the State University at Buffalo. For some reason, however, Truzzi neglected to put my name on the list, so I wasn’t invited. Then, when they realized I was one of the original founders (along with Martin and Randi), they decided to invite me. I think Martin and Randi insisted on it. Everyone else had their way paid to the conference except me. And they refused to pay my expenses because they said I wasn’t in the original plans. So even though I was one of the three original founders, I had to pay my own way to this meeting! Also there were Phil Klass and Dennis Rawlins, who would become founding members.

Skeptic: This, then, was the founding of CSICOP and the Skeptical Inquirer?

Hyman: Yes. Truzzi’s The Zetetic newsletter was published two times the first year as a small-sized journal. The first issue dealt with the astrology controversy surrounding the so-called “Mars Effect.” Well, Rawlins and Truzzi didn’t really get along all that well, and Rawlins thought Truzzi was a closet Satanist or something, so Rawlins left the group a few years later after the problems surrounding the handling of the Mars Effect controversy. Complicating matters, Truzzi wanted to make the publication an academic journal, giving all sides an equal chance to speak their mind on any given issue, but others in the group were afraid that this could lead to the journal being taken over by the other side. The controversy over the purpose and goals of the magazine, plus personal differences with Paul Kurtz, resulted in Truzzi’s resigning as editor and leaving CSICOP. He was replaced by Ken Frazier, who was at that time an editor of Science News.

Making matters worse, The Zetetic featured an article on Scientology. Shortly thereafter a Scientologist got hold of a CSICOP letterhead, wrote a bogus letter on it and sent it out to various people, making CSICOP really look like we were witch hunters and loose cannons. (We found all this out a few years later through the Freedom of Information Act.)

Skeptic: What would it take to convince skeptics that there was such a thing as, say, psychic power? And here I am thinking of Alfred Wegener, who theorized about the possibility of continental drift in the 1920s, but it wasn’t until the 1960s that the theory gained acceptance because it was not until then that the mechanism of plate tectonics was shown to be the driving force. In other words, evidence of continental drift alone was not enough. Scientists needed a mechanism to explain how it could happen before they accepted it. Is this the case with psychic power? Even if there were evidence, would we still demand a brain mechanism before accepting it?

Hyman: That’s right. I think of our research as a three-legged stool:

- Theoretical underpinning;

- Empirical evidence; and

- Research program.

Parapsychologists have a research program, but they have neither solid repeatable empirical evidence nor a theoretical underpinning.

Another thing that bothers me is the idea of a financial challenge to psychics. Scientists don’t settle issues with a single test, so even if someone does win a big cash prize in a demonstration, this isn’t going to convince anyone. Proof in science happens through replication, not through single experiments. Randi understands this, and he is careful to say this, but it gets lost in the PR effort. But many in the scientific community worship Randi because they wish they could be him. They wish they didn’t have the constraints of academia. He’s out there in the trenches, on the front line, and they envy him for that.

When I was involved in investigating the remote viewing experiments by the CIA, I had a similar discussion with Jessica Utts and Ed May, who wanted to know what it would take to convince me. I told them a story about a guy in St. Louis who said he could do remote viewing, but when we set up the experimental protocol he demanded that if the test came out positive I would say “I now believe.” I explained to him that “belief” is subjective, and I talked about how at magic conferences I have fooled even the best magicians in the world, and they have fooled me, so someday a psychic is going to come along and do something that I cannot explain, but this does not mean there is a real psychic effect here. It may just mean that I’ve been fooled. When I investigated the Ganzfeld experiments, for example, it took me three years to figure out what was going on.

Skeptic: Are there some things you can partially explain but in which there is still an element of mystery?

Hyman: Oh sure. In the CIA remote viewing experiments, for example, I can find some flaws, but their statistics look fine. This is not enough, however, to say that there is a real effect here. We have to wait and see if these experiments can be replicated. Dean Radin, in his book The Conscious Universe, took me to task for saying that I would never believe. Well, I didn’t say that. I just explained that these very rare cases where there is some statistical anomaly do not prove a real psi effect.

In Ed May’s remote viewing experiments, for example, he discovered that when he was the judge he got much better results than his other judges did because, he said, he knows the peculiarities of the answers of the remote viewers whose answers were never very specific. So he could interpret them one way or the other.

Skeptic: Did you make a conscious choice to become an academic scientist mainly interested in testing claims, rather than an activist out there debunking claims?

Hyman: I discovered early on that by playing the scientific game I lost the PR game. As a scientist I have to qualify my answers, and this does not make for good PR or good sound bites. For example, when the CIA remote viewing experiments story broke and Nightline had a show on it, I was supposed to be on. When Ed May objected to my participation they got the head of the CIA instead. But he didn’t really know the statistics or the research protocol. And even when I did do some shows on it, like Larry King Live, they mostly wanted to talk about the waste of taxpayer’s money. They definitely did not want to talk about the data, the research methods, or the statistics.

Skeptic: What does the future hold for skepticism?

Hyman: Good scientific research is very costly and time consuming. Given limited resources, I think we get more bang for our buck if we focus on the media and education—the opinion makers— instead of serious research. I think we need to be a credible source of reliable information.

Frankly I think it is useless to offer cash prizes and debunk psychics on television. You can do that until doomsday. The public doesn’t gain anything from this. I think we need to educate the public on the reason why these things appear real, on why we believe, on how we are deceived. These are epistemological questions. Most of us most of the time make decisions not on the basis of logic or science or rationality, but on emotion. Debunking without lessons is a waste of time.

I like to tell the story of the 19th-century scientist Michael Faraday who took time out from his scientific research to investigate table turning and spiritualism. Members of Parliament were actually consulting these tables for advice, so Faraday proposed a test, not to debunk these spiritualists, who he believed to be sincere, but to see what was really going on. On a table he structured layers on layers on layers of table tops tied together with elastic bands, and down the side of them he put pencil marks. If they were pushing the table from the top, the pencil marks would leave broken hash marks down the side. He also put a reed on the side to see if it moved. When the spiritualists’ eyes were opened, the reed did not move. When their eyes were closed, the reed and table moved! Faraday was actually conducting the very first biofeedback experiment. He showed not that these spiritualists were fakes, but that they were unconsciously moving the table themselves. They were self-deceiving.

The purpose of this story is to show that, in my opinion, it is more interesting, and in the long run more important, to show unconscious bias than outright trickery. Obviously the latter is important in the short term—we need to do both— but in the long term I want to learn something about the psychology of belief. ![]()