About this week’s eSkeptic

In this week’s eSkeptic, Richard Grigg explains why he thinks Douglas Navarick’s empirical God-hypothesis fails. If you haven’t yet read Navarick’s article, or the previous debate between Dave Matson and Navarick, you may want to read those first, then come back here and read Grigg’s challenge (below), followed by Navarick’s response.

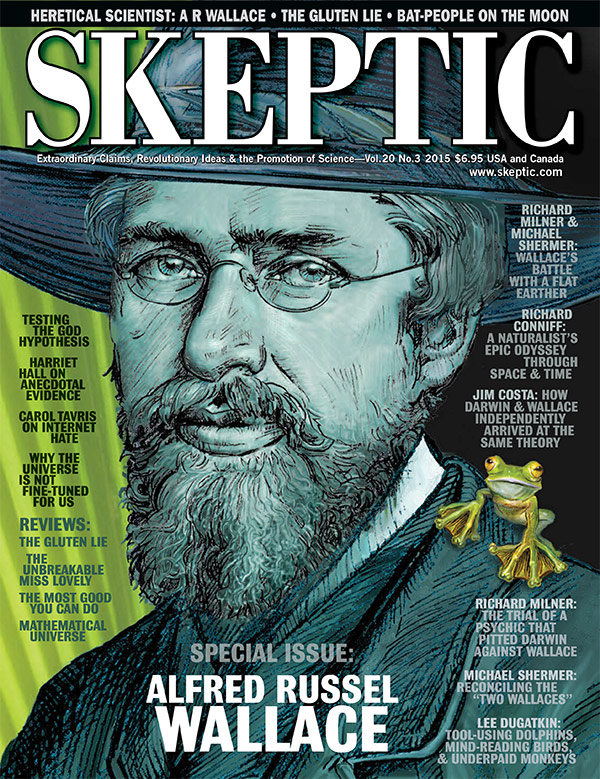

Navarick’s article “The ‘God’ Construct: A Testable Hypothesis for Unifying Science and Theology,” appeared in Skeptic magazine 20.3 (2015).

Why Douglas Navarick’s Empirical God-Hypothesis Fails

by Richard Grigg

In his “The ‘God’ Construct: A Testable Hypothesis for Unifying Science and Theology” that appeared in Skeptic (Vol. 20, No. 3, 2015), Douglas J. Navarick lays out a laudably clear and thorough argument on behalf of what he regards as an empirical approach to at least one, potentially unorthodox, version of theism. He is to be congratulated for coming up with something genuinely new to say on a subject that has been nearly talked to death over several thousand years of Western debate. At the same time, Navarick’s approach contains a fatal flaw, one that brings down not only his own enterprise but any version of theism that suggests that a supernatural force has even the least influence upon the natural universe.

Navarick zeroes in on the question of whether the claim that the origin of life on Earth is to be explained through abiogenesis has sufficient evidence to back it up. “Biogenesis” is a word that we derive from the Greek “bios,” life, and “genesis” meaning origin or source. When the Greeks put an “a” (the Greek alpha) in front of a word, the so-called “alpha privative,” it reverses the word’s meaning. Most contemporary scientists assume that the first truly living thing, something more than a virus—specifically a living cell—arose via abiogenesis. This suggests that a chemical soup that did not itself contain any living things came together in such a fashion that a living cell emerged.

Of course decades of laboratory experiments that have attempted to reproduce the conditions of the early Earth that might have led to the appearance of the first cell have all come up empty handed, in that no mixing of likely precursor chemicals has ever actually resulted in a living cell. All of the living cells ever observed have derived from other living cells. This, argues Navarick, is absence of evidence, an absence that is sufficiently potent to register as evidence of absence. Perhaps life cannot come from something not itself living, then, but only from something of a quite different order. And, if so, perhaps it is an empirically defensible hypothesis that a God, one that need not be conceived in any more than the most minimalist terms, had to create the first cell or cells. Navarick defines his minimalist god as “a force that operates both through and independently of natural laws.”1

The fatal flaw in Navarick’s argument is already visible in this brief definition, as it is in his earlier admission that “A precondition for conducting a scientific analysis of the evidence of God is an acknowledgement that science is capable of identifying supernatural influences in the natural world.”2 What brings both of these formulas to grief is none other than one of the most basic laws of physics, the first law of thermodynamics, articulated in the 19th century: energy can be neither created nor destroyed; it can only change its form. The energy stored in the bonds of the gasoline molecules in my car’s gas tank, along with the energy in the oxygen molecules in the air, can make my car move down the road. Chemical energy is turned into kinetic energy, the energy of motion. But if we could add up every bit of energy with which we started and every bit with which we ended up, we would come up with the very same amount in each case. Things get tricky here in real-world examples, because the energy stored in fuel and oxygen doesn’t get completely translated into the energy of motion; much gets transformed into friction and heat energy, for example. But at the end of the day, energy has been neither created nor destroyed, just changed from one form into others.

Now any claim that a supernatural entity can have an influence within the natural world or can use already existing natural entities and phenomena in order to effect a new state of affairs immediately runs afoul of the conservation of energy. Let us begin with a simple analogy. There is a rake intended for raking leaves hanging on a hook in my garage. If I reluctantly pick up the rake, head out into my front lawn, and begin raking, what is actually moving the leaves? Proximately or most immediately, it is the rake. But the rake would still be hanging in my garage and would not be moving back and forth across my lawn if it were not for the energy that my body contributes to it. My body most definitely adds energy to the equation, even though one might choose to say that I work through the rake, that I am the “primary cause” utilizing a “secondary cause” to accomplish my purpose, language found in Medieval theologians such as Thomas Aquinas who believed that God was the primary cause who acted through secondary causes, the latter being finite, natural objects.

But here is the rub: if we consider my actions and that of the rake in artificial isolation from the rest of the world, the law of conservation of energy appears to be violated—I have not just changed the form of the energy contained in the rake (the inert rake’s energy includes, for example, the rapid motion of its constituent atoms and the potential energy it has by being suspended in a gravitational field). Rather, I have actually added new energy to the rake, and it has been necessary for me to do so if the rake is going to be used for its intended purpose of cleaning the leaves off of my yard. But when we remove the artificial brackets and place the energy that my body expends and the rake’s inherent energy within the whole surrounding natural universe, the conservation of energy holds. For instance, the energy that my body produces through cell metabolism is not a matter of creating new energy out of whole cloth, but of changing the form of the energy contained in the food stuffs that I imbibe and the air that I breathe.

Now take the idea central to Navarick’s contention, and to all claims that a supernatural being has effects within the natural world: the supernatural cannot act “through” the natural world and its physics without violating conservation of energy. Just as the rake wouldn’t move without my adding energy via my bodily motions, so the purely natural interaction of purely natural entities must obey the conservation law. But if the natural universe is left in this way to its own devices, Navarick wants to argue that these purely natural phenomena can never produce the first genuinely living thing. For that to happen, Navarick suggests, the supernatural must interact with the natural. But that will involve the supernatural adding energy (not just changing the form of energy) from outside the natural world as surely as my going to work with the rake adds new energy to the energy that the rake already possesses. But where my body’s interaction with the rake, when considered within its total natural environment, does wholly obey the conservation law, Navarick’s scenario does not: a supernatural entity, by definition, stands outside the closed physical world in which the laws of physics apply. And even if it were possible to imagine a deity not subject to those laws within that God’s own internal nature, the moment that that deity attempts to utilize or work through phenomena in the natural world, energy is being illicitly transported into that world from outside it, and not simply changing form. The conservation law is violated.

This is a gargantuan “woops!” That is, we should not underestimate the impossibility of countenancing any violation of the first law of thermodynamics. If energy were not conserved and could appear ex nihilo in our universe, whether via a supernatural agent or some other source, our reality would be a very different one from the reality in which we do in fact reside. But would the sort of violation of energy conservation implicit in Narvarick’s proposal necessarily be detectable? And if it were not, might it be possible to argue that Navarick’s hypothesis still has a chance of being correct? Perhaps even if it violates the first law of thermodynamics, the fact that we could never detect that violation renders the problem null and void, especially given the school of philosophy which holds that “laws” of nature are nothing more than generalizations derived from what we observe in the world around us. Perhaps this invisible contradiction between supernatural action within the natural world on the single matter of the origin of life and conservation of energy is akin to the contradiction between General Relativity and quantum theory. Each theory appears to hold within one segment of reality. An overly simple but oft-stated description of this situation is to say that quantum theory applies on the level of the very small, such as the atomic and subatomic realms, whereas General Relativity applies on larger scales.

But note how physicists react to this particular apparent contradiction. They do not simply shrug their shoulders and forget about the problem. Rather they tend to choose one of two options: either quantum theory and/or General Relativity is not a complete theory; there is some yet undiscovered theory that will be able to unite them. Or—and this is a smaller group of physicists—they conclude that there may be some conundrums that are simply beyond the capacity of the human mind to resolve; after all, there is no survival value to understanding these matters (but, of course, neither is there any obvious survival value to being able to solve many perfectly solvable mathematical equations).

But suppose we grant that if a supernatural force violated the first law of thermodynamics when it brought the first living thing into being, that violation would be invisible. It turns out that this only makes Navarick’s argument weaker. Being unable to observe any violation of the conservation law here is a lack of evidence for that violation, and when we find ourselves in that situation, it is certainly the more rational choice to adhere to an established physical law.

But wait, there’s more! While I have thus far confined myself to the origin of the very first cell, from which I am presuming all life on Earth derives, Navarick actually holds that the supernatural force that he suggests interfered in our world in order to create that first cell actually has to be present in all cells that will ever exist. That is, he wants to reinstate the long-abandoned philosophy called vitalism. Navarick argues that he has made “a reasonable case for the existence of a supernatural force that produced the first living cell and since then has continued to produce cells in such numbers that they now penetrate virtually every nook and niche of the planet.”3 If a supernatural force entered into the birth of the very first cell, that would be a violation of the conservation of energy, but it would be an undetectable violation. By contrast, if a supernatural force is inserting itself into the natural processes going on within every living cell, that would be a violation of energy conservation that is in principle quite detectable. If such vitalism were to occur, and a biologist carefully examined the energy transactions in a cell, he or she would find that more energy was being expended than was contained within the natural components of the cell. I am not willing to hold my breath on that discovery.4 ![]()

References

- Navarick, D. J. 2015. “The God Construct: A Testable Hypothesis for Unifying Science and Theology.” Skeptic, 20 (3), 47. Emphasis mine.

- Ibid. Emphasis mine.

- Ibid., 51. Emphasis mine.

- My contention that the conservation of energy causes problems for the notion of divine action in the world is hardly my own invention; it has been widely discussed. However, I do examine it at length in Grigg, R. 2008. Beyond the God Delusion: How Radical Theology Harmonizes Science and Religion. Minneapolis: Fortress; and Grigg, R. 2012 “Religion and Magical Thinking: Is Religion a Delusion?” In Science and the World’s Religions, ed. Patrick McNamara and Wesley J. Wildman. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. Vol. 3, 195–219.

About the Author

Richard Grigg, Ph.D. is Professor in the Department of Philosophy, Theology, and Religious Studies at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut. He is the author of eight books and numerous articles on the subject of radical Western religious thought.

Biogenesis vs. Abiogenesis, Not Thermodynamics, Decides the Issue of Life’s Origin

by Douglas J. Navarick

Richard Grigg presents a challenge to my science-based “God” construct that he claims refutes both my hypothesis and any form of theology stating that a divine power interacts with nature. He argues that to alter a natural system, a supernatural power would necessarily violate the first law of thermodynamics—conservation of energy—which holds that the total amount of energy in the universe is constant. According to Grigg, the violation would occur because the power would have to add energy to the system that it was changing from a source outside the natural universe. (Actually, no energy would have to be added, as will soon be shown.)

Although the issues Grigg raises are important to address, it is not because they challenge the validity of the “God” construct. The issues are irrelevant. The test is whether life can be produced from non-life. If abiogenesis failed, then a supernatural (non-material) power in the universe would be established by default and physics would simply have to find a way to accommodate this new reality.

So in terms of assessing the evidence for the “God” construct, it’s all about artificial life. Hypothetical violations of conservation of energy are not a substitute for researchers’ continuing inability to demonstrate that abiogenesis really happens.

Still, if a supernatural power interacted with cells as required by the “God” construct, and its actions were to be understood within a scientific framework, then the dynamics of this influence would eventually need to be described in empirical terms, and ideally without requiring a violation of conservation of energy. In a follow-up article1 to the one discussed by Grigg, I have already outlined such a process involving no transfer of energy from the supernatural power to the cell. Here I will elaborate on the evidence and explore its scientific and theological implications.

The cryopreservation model. As I previously discussed, life is either an emergent (material) or a transcendent (non-material) property of cells. Emergent means that life is the product of relationships that exist among the cell’s structures and biochemical reactions. Transcendent means that life is an independent property and requires no biochemical activity to sustain it. I cited evidence for transcendence from the process of cryopreservation. Life appears to act as a kind of catalyst that permits biochemical reactions to begin, at which point natural processes take over.

Here’s the evidence: In cryopreservation, single cells and tissues can be frozen to the point where metabolism stops but the cells remain alive if the cell wall is intact. This shows transcendence. When living cells are thawed, the pre-existing property of life allows metabolic activity to resume. This transcendent influence on the cell adds no energy to it. If molecular biologists suspected that the first law of thermodynamics was being violated during the reactivation of cells, then it would have to be a very closely held secret.

Evidence for transcendence from the Venter Institute. The J. Craig Venter Institute is a genomic research organization located in Rockville, Maryland and La Jolla, California. Perhaps its most famous accomplishment has been the creation of a synthetic bacterial cell that replicated itself using manufactured DNA. In May, 2010 some media outlets misinterpreted Venter’s demonstration and breathlessly announced that Venter had achieved synthetic life, a claim repeated by Venter himself in a 2010 “Ted in the Field” presentation viewable on YouTube (but later clarified to dispel any misunderstandings about whether life had been created).

There was such a strong public reaction to the news that President Obama asked his Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues to examine the implications of artificially creating life. Here is what they said2:

“Q: Did the Venter Institute scientists “create life?”

A: No. In our deliberations, we heard that while Venter’s achievement marked a significant technical advance in demonstrating that a relatively large genome could be accurately synthesized and substituted for another, it did not amount to the “creation of life.” The researcher’s man-made genome was inserted into an already living cell. The synthesized genome itself was a variant of a genome of an existing species. The technical feat of synthesizing a genome for its chemical parts so that it becomes self-replicating when inserted into a bacterial cell of another species, while significant, does not represent the creation of life from inorganic chemicals alone.

In addition to constituting a concession to biogenesis, Venter’s achievement provides further evidence that life is a transcendent property of the cell. To insert the new DNA, Venter had to remove the cell’s existing DNA. Yet even without this critical structure, the cell remained alive. If life emerged from a cell’s structure and biochemical reactions, then Venter’s cell should have died abruptly with removal of the DNA. As with cryopreservation, life transcended material reality.

Maimonides may have had it right. The cryopreservation model represents life as a supernatural influence that acts as a catalyst rather than by participating directly in the cell’s functions. The 12th-century philosopher and theologian, Moses Maimonides, seems to have envisioned such a process in his efforts to explain how an incorporeal being could bring about changes in the natural world:

There are actions that do not depend on impact, or on a certain distance. They are termed ‘influence’ (or ‘emanation’), on account of their similarity to a water-spring…[that] sends forth water in all directions…and continually waters both neighboring and distant places…whenever an object is sufficiently prepared, it receives the effect of that continuous action, called ‘influence’ (or ‘emanation’).3

In cryopreservation, a cell that is structurally intact is “sufficiently prepared” to receive the influence that life will have on its biochemical activity when the cell thaws. There is no necessity for life to physically act on the cell by adding energy to it the way Richard Grigg would have to add energy to the rake in his example that purports to illustrate the “fatal flaw” in the “God” construct.

“But wait, there’s more!” I have proposed that the supernatural power that produced the first living cell has continued to produce them. Grigg maintains that this concept of continuity in supernatural influence is indefensible because if the supernatural continued to act upon cells, researchers would have observed that the cells were expending more energy than they contained. However, cryopreservation shows that life can bring about biochemical activity in a cell without adding to its store of energy. This process can explain why researchers have observed no anomalies in cell reproduction.

At the close of my article on the “God” construct I suggested the possibility that life is God. From a strictly scientific point of view the life-is-God concept has the theoretical advantage of parsimony. Rather than speaking of two theoretical principles, abiogenesis for the first cell and biogenesis for all subsequent cells, we would only need one, biogenesis. If a theistic God existed before the first cell became active, and God = life, then that cell and all subsequent cells would be instances of the same principle—life comes from life. ![]()

References

- Navarick, D. J. 2015. “Abiogenesis: Hypothesis or Doctrine”. eSkeptic, September 30, 2015. To be republished in Skeptic, 2015, 20(4).

- Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues, December, 2010.

- Quoted in Jammer, M. 1999. Einstein and Religion: Physics and Theology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, p. 213.

About the Author

Douglas Navarick is an experimental psychologist and Professor of Psychology at California State University, Fullerton. He regularly teaches courses in Introductory Psychology and Learning and Memory. Since the 1970s Navarick has published research articles on choice behavior in pigeons and humans and is currently investigating how we make intuitive moral judgments.