In this week’s eSkeptic:

JULY 15–AUGUST 2, 2018

Seats still available! Don’t miss this spectacular tour packed with world-renowned geological sites, Celtic history, and the charm of Irish culture and countryside

Questions? or to secure your spot: Contact DreamMaker Travel by email at [email protected] or call 1-561-204-3100.

Looking to save a little money by having a roommate? We’ll try to match you up with someone. Contact DreamMaker Travel.

SCIENCE SALON # 18

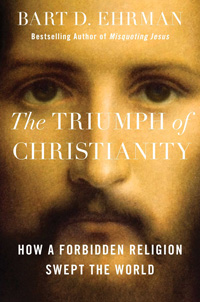

Michael Shermer in conversation with Bart Ehrman: How a Forbidden Religion (Christianity) Swept the World

In this remote Science Salon (recorded on February 19, 2018), Dr. Shermer converses with the great bible scholar and historian Dr. Bart D. Ehrman, the Distinguished Professor of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Ehrman is a leading authority on the New Testament and the history of early Christianity and the author of 8 Teaching Company courses and a number of New York Times bestselling books, including Misquoting Jesus and How Jesus Became God. In his new book, The Triumph of Christianity: How a Forbidden Religion Swept the World, Dr. Ehrman explores how a tiny sect of just 20 people at the time of Jesus’ crucifixion in 30 CE became 25 to 35 million Christians by 400 CE. Imagine if the couple of dozen Branch Davidians living near Waco, Texas in early 1990s, instead of being incinerated by Federal agents in a botched stand-off, went on to convert two billion people around the world to their religion. That is what early Christians did. How did they do that?

Shermer and Ehrman also discuss the modern atheism movement, how Jesus became a Republican in the second half of the 20th century, the intractable (for Christians) problem of evil, the problem of identity for Jesus (how could he be both man and God?), what pre-Christian pagans believed about the gods, what early Christians had to offer pagans that other religions didn’t, how religions invented the afterlife and what people believed before the rise of Christianity about what happens after you die, and other fascinating topics.

This interview was recorded on February 18, 2018 as part of the Science Salon series of dialogues hosted by Michael Shermer and presented by The Skeptics Society, in California. Support our work by making a donation.

Check Us Out on YouTube.

Science Salons • Michael Shermer

Skeptic Presents • All Videos

Show Your Support

Subscribe to our YouTube Channel and get notified instantly when we post new content! Do you like what you see? Show your support for our work. Your ongoing patronage is vital to our organization’s mission.

![Universum by Heikenwaelder Hugo, Austria, www.heikenwaelder.at [CC BY-SA 2.5], via Wikimedia Commons is a colorized version of The Flammarion wood engraving by an unknown artist that first appeared in Camille Flammarion’s L’atmosphère: météorologie populaire (1888).](https://www.skeptic.com/eskeptic/2018/images/18-02-21/Universum.jpg)

ABOVE: Universum by Heikenwaelder Hugo, Austria [CC BY-SA 2.5], via Wikimedia Commons is a colorized version of The Flammarion (by Anonymous [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons) — a wood engraving by an unknown artist that first appeared in Camille Flammarion’s L’atmosphère: météorologie populaire (1888). The image depicts a man crawling under the edge of the sky (as if it were a solid hemisphere) to look at the mysterious Empyrean beyond. The caption underneath the engraving (not shown here) translates to “A medieval missionary tells that he has found the point where heaven and Earth meet…”

The notion that there can be more than one universe at first seems oxymoronic. In this week’s eSkeptic, Peter Kassan discusses the problematic notion of a multiverse arising from a highly speculative interpretation of quantum mechanics. This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 22.1 (2017). Buy this issue.

Trouble in the Multiverse

The boundary between science and mere scientific speculation can be elusive. Albert Einstein famously performed only thought experiments, but those mere ideas yielded counterintuitive predictions leading to experiments conclusively confirming his revolutionary theory. Other thought experiments imagined by Einstein and his colleagues meant to demonstrate the impossibility of quantum theory actually turned out to be conductible. When performed, those experiments refuted Einstein’s arguments and help confirm the quantum.

I think I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics.

Recently, however, some much more troublesome (and troubling) ideas have been advanced by some astrophysicists and cosmologists: string theory and the multiverse. The motivation and justification of string theory is to bring order to the menagerie of subatomic particles. String theory posits that we live not in a four-dimensional universe of space-time (once a highly counterintuitive notion, but now firmly established) but in a universe of many more dimensions (10 or 11, at last count), most of which we ordinary humans fail to notice simply because we’re unable to move in or through them (and because they’re very, very small relative to the more familiar ones). The usual analogy is that of two-dimensional creatures living in a flatland—on a surface (either a plane extending infinitely in two dimensions or a bounded one such as the surface of a sphere)—who would be unable to perceive a third dimension (and perhaps even to conceive of it). With 10 or more spatial dimensions, we’re told, we can conceive of subatomic particles not as point-like entities but as string-like ones vibrating in modes that can account for the variety of particles actually observed. However, no testable predictions have yet been advanced to confirm or disprove the idea.

At several stages in the history of science, some theories and entities were posited only because they were useful, although many scientists working at the time doubted their physical reality. The heliocentric model of the solar system, for example, was initially accepted not as physically true but simply because its mathematics made it simpler to account for the apparent motion of the planets. Similarly, the atomic nucleus, the electron, and the photon were all at first considered useful concepts having no physical reality. It was sometimes not even clear that the theories could ever lead to experimentally testable predictions. […]