In this week’s eSkeptic:

SHERMER RESPONDS TO PIGLIUCCI

Moral Philosophy and its Discontents

Michael Shemrer responds to Massimo Pigliucci’s critique of Shermer’s Scientific American column on utilitarianism, deontology, and rights. (Illustration above by Izhar Cohen.)

My May 2018 column in Scientific American was titled “You Kant be Serious: Utilitarianism and its Discontents”, a cheeky nod to the German philosopher that I gleaned from the creators of the Oxford Utilitarianism Scale, whose official description for those of us who score low on the scale read: “You’re not very utilitarian at all. You Kant be convinced that maximizing happiness is all that matters.” The online version of my column carries the title (which I have no control over): “Does the Philosophy of ‘the Greatest Good for the Greatest Number’ Have Any Merit?” The answer by any reasonable person would be “of course it does!” And I’m a reasonable person, so what’s all the fuss about? Why was I jumped on by professional philosophers on social media, such as Justin Weinberg of the University of South Carolina on Twitter @DailyNousEditor, who fired a fusillade of tweets, starting with this broadside:

Disappointing that @sciam is contributing to our era’s ever-frequent disrespect of expertise by publishing this ill-informed & confused @michaelshermer column on moral philosophy. (1/12) https://bit.ly/2H7LRPT

I sent a private email to Justin inviting him to write a letter to the editor of Scientific American that I could then respond to—given that Twitter may not be the best medium for a discussion of important philosophical issues—but I never received a reply. […]

FLASHBACK SCIENCE LECTURE

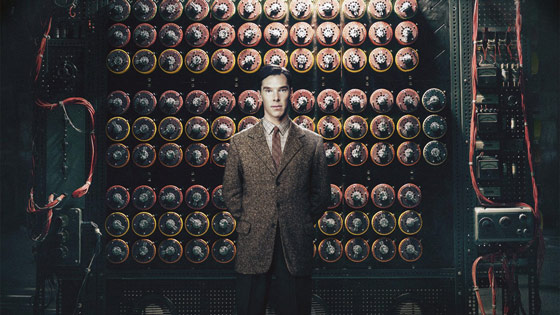

Dr. Andrew Hodges discusses Alan Turing: The Enigma, the book that inspired the film The Imitation Game starring Benedict Cumberbatch

This lecture was recorded on December 7, 2014 — one of the last in a series of over 350 Distinguished Science Lectures presented by the Skeptics Society since 1992.

About this lecture

It is only a slight exaggeration to say that the British mathematician Alan Turing (1912–1954) saved the Allies from the Nazis, invented the computer and artificial intelligence, and anticipated gay liberation by decades—all before his suicide at age 41. In November a major motion picture starring Benedict Cumberbatch as Turing will be released, based on the classic biography by Dr. Andrew Hodges, who teaches mathematics at Wadham College, University of Oxford (he is also an active contributor to the mathematics of fundamental physics).

Hodges tells how Turing’s revolutionary idea of 1936—the concept of a universal machine—laid the foundation for the modern computer and how Turing brought the idea to practical realization in 1945 with his electronic design. Hodges also tells how this work was directly related to Turing’s leading role in breaking the German Enigma ciphers during World War II, a scientific triumph that was critical to Allied victory in the Atlantic. At the same time, this is the tragic story of a man who, despite his wartime service, was eventually arrested, stripped of his security clearance, and forced to undergo a humiliating treatment program—all for trying to live honestly in a society that defined homosexuality as a crime.

Order Alan Turing: The Enigma, the book that inspired the film The Imitation Game.

Learn more about the Distinguished Science Lectures Series. Watch past Distinguished Science Lectures. Learn about Science Salon — our new series of conversations between Dr. Michael Shermer and leading scientists, scholars, and thinkers, about the most important issues of our time. Watch past Science Salons.

Become a Patron

You play a vital part in our commitment to promote science and reason. Your ongoing patronage will help ensure that sound scientific viewpoints are heard around the world.

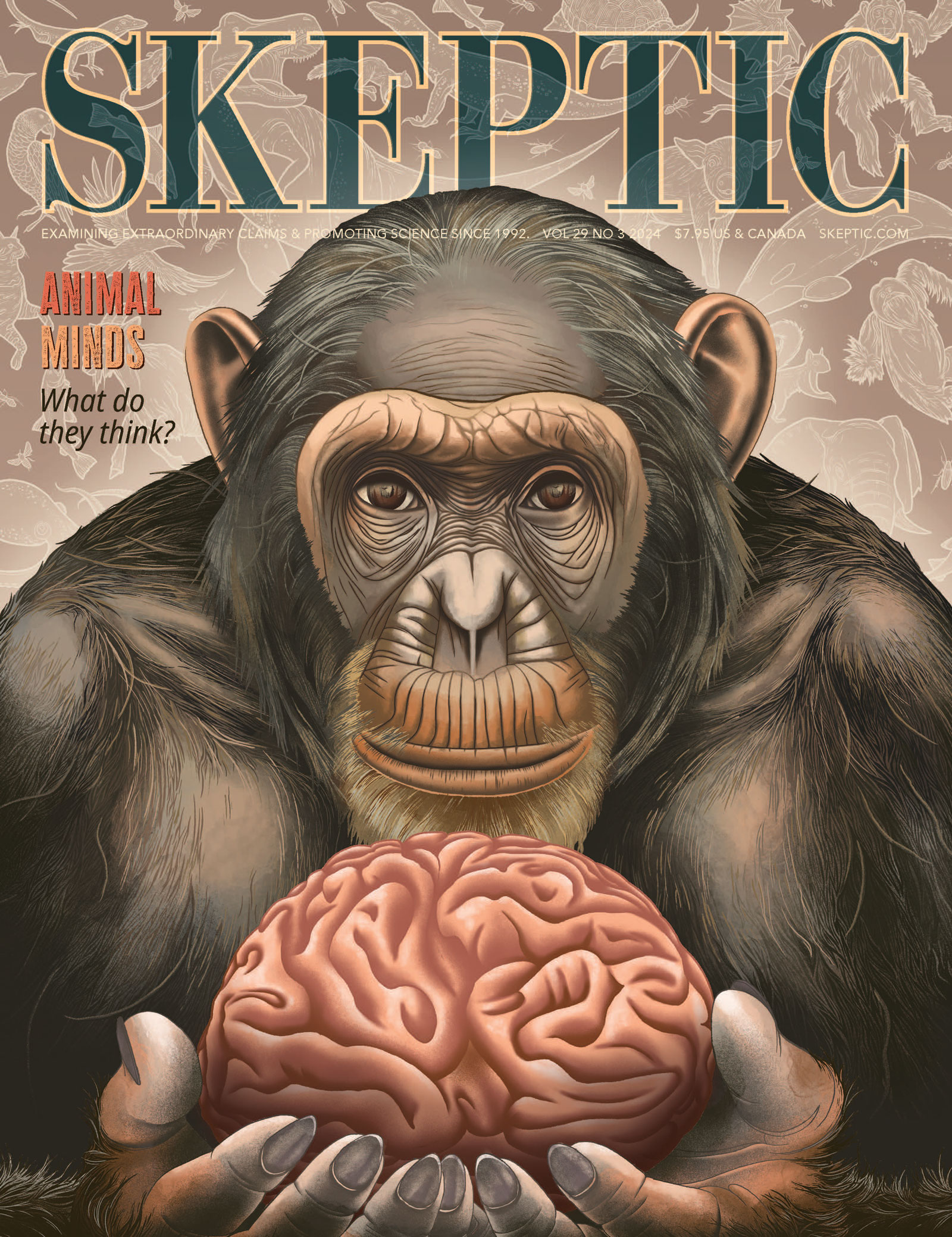

Nathan H. Lents and Lila Kazemian discuss evidence from a variety of disciplines as disparate as animal behavior and moral theology that point toward more humane, efficient, and effective responses to crime and punishment that work in concert, rather than in conflict, with our evolutionary psychology. This column appeared in Skeptic 22.4 (2017).

What Biology Can Teach Us About Crime and Justice

The last half-century has brought about a number of pressing social and criminal justice issues around the world. These social changes have been particularly tumultuous in the United States. From the civil rights movement to rising incarceration rates, the U.S. has undergone a number of social movements and interconnected paradigm shifts that have raised concerns about the issue of justice, and that have moved a growing number of citizens in and out of social exclusion.

Any effort to advance towards a more just society requires us to ponder the extent to which the quest for justice and the ability to empathize with the “other” are biological instincts or socially learned behavior. Recent studies of animal behavior provide new insight into the biological and social roots of empathy and justice. In this piece, we explore the application of these findings to the human experience with punishment, forgiveness, and justice.

Animal Behavior and Social Justice

The study of animal behavior is currently experiencing a renaissance based on a flurry of groundbreaking work and a rebirth in our thinking. In the late 19th century, naturalists including Charles Darwin and Thomas Huxley spoke more expressively about the minds of animals, but this was soon followed by an austere scientific stoicism, at least in the West, that labeled as anthropomorphism any attempt to discuss an inner experience for animals. This trend lasted well into the second half of the 20th century and is only stubbornly retreating in the face of undeniable evidence that animals have complicated mental and social lives.1

The field of ethology, formally the study of animal behavior in their natural setting, has been rebranded by some scholars as the study of animal minds. Among the most important pioneers in this field are the “trimates:” Jane Goodall, the late Dian Fossey, and Birutë Galdikas, the scientists who made the most significant contributions to our knowledge of the natural behaviors of chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans, respectively.2 Their work has inspired scientists from around the globe to conduct more thorough investigations, revealing that that social animals express a rich and complicated cultural fabric that often bears a striking resemblance to our own.

Penguins trade resources for sex. Dolphins and elephants pass the mirror test for self-awareness. Mice will skip food in order to rescue a trapped companion. Crows engage in a death ritual for fallen comrades. Many animal species display the clinical symptoms of grief when a close affiliate dies. Prairie dogs have developed an entire language for warning each other about threats (including humans) that includes descriptors for color, size, and shape. The closer we look, the more complexity we find, and the more we realize that the animal and human experiences are not so different.3 […]

MONSTERTALK EPISODE 154

The Chicago Mothman—Site Seeing

Allison Jornlin is a paranormal researcher and host of The Otherside podcast. She’s been diligently researching the recent (2017–present) Chicago Mothman sightings as popularized on Lon Strickler’s Phantoms and Monsters website and book. You can find all of Allison’s on-site video recordings from her Mothman research on YouTube.

Get the MonsterTalk Podcast App and enjoy the science show about monsters on your handheld devices! Available for iOS, Android, and Windows. Subscribe to MonsterTalk for free on iTunes.