SCIENCE SALON # 50

Dr. Rachel Kleinfeld — A Savage Order: How the World’s Deadliest Countries Can Forge a Path to Security

In this episode of the Science Salon Podcast, Michael Shermer speaks with Dr. Rachel Kleinfeld, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, where she focuses on issues of rule of law, security, and governance in post-conflict countries, fragile states, and states in transition. As the founding CEO of the Truman National Security Project, she spent nearly a decade leading a movement of national security, political, and military leaders working to promote people and policies that strengthen security, stability, rights, and human dignity in America and around the world.

In 2011, former secretary of state Hillary Clinton appointed Kleinfeld to the Foreign Affairs Policy Board, which advises the secretary of state quarterly, a role she served through 2014. Dr. Kleinfeld has consulted on rule of law reform for the World Bank, the European Union, the OECD, the Open Society Institute, and other institutions, and has briefed multiple government agencies in the United States and abroad.

She is the author of Advancing the Rule of Law Abroad: Next Generation Reform (Carnegie, 2012), which was chosen by Foreign Affairs magazine as one of the best foreign policy books of 2012. Named one of the top 40 Under 40 Political Leaders in America by Time magazine in 2010, Kleinfeld has been featured in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, Fox News, and other national television, radio, and print media.

Her new book is A Savage Order: How the World’s Deadliest Countries Can Forge a Path to Security. In this conversation we discuss her new book, specifically:

- What it says about human nature that people so easily turn to violence when there is no central authority.

- What she learned about law and order growing up in libertarian Alaska, and how she got interested in studying violence in failed states around the world.

- Why studying history and reading the classics (like Thucydides) was the best preparation she had for her job.

- Lessons from The Godfather on what happens when governments become corrupt—strong men promising security and protection from corruption rise up.

- Pace the Godfather, what happened in the Republic of Georgia after the fall of the Soviet Union, and why violence spiked and then declined.

- Why dictators like Saddam Hussein do not actually keep violence down in their countries because state-sponsored violence goes unrecorded.

- Her experiences living and working in Russia and other countries undergoing turmoil.

- Putin and Russian today and what they want.

- Columbia as a model of a failed state and what the U.S. did there to help turn things around.

- How the Wild West of the United States was tamed.

- Why violence is higher in the southern United States, and why lynching and other hate crimes were driven more by political power and expediency than by racial hatred (data shows that such crimes peaked before elections).

- How the 21st century is so different from the 20th century’s battle of “isms”: communism, socialism, Leninism, Stalinism, Trotskyism, liberalism, individualism, idealism, humanism, etc. We’re living in a different world today.

- We’re about to colonize Mars and establish a new society there. What parts of government should we take with us there, and what parts should we leave behind? That is, what have we learned over the millennia in terms of good vs. bad governance.

Listen to the podcast via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, iHeartRadio, and TuneIn.

This remote Science Salon was recorded on January 4, 2019.

Check Us Out On YouTube.

Science Salons • Michael Shermer

Skeptic Presents • All Videos

If you enjoy the video, audio, and written content we produce, please show your support by making a donation. Your ongoing patronage is vital to our organization’s mission to promote science and critical thinking.

Michael Shermer responds to Richard Weikart’s critique of his January 2019 column in Scientific American: “Stein’s Law and Science’s Mission: The Case for Scientific Humanism.” Weikart is a California State University historian and a Senior Fellow of the Discovery Institute’s Center for Science and Culture (an Intelligent Design creationism advocacy organization).

A Pathway to Objective Morality

Why the Case for Scientific Humanism is Rational

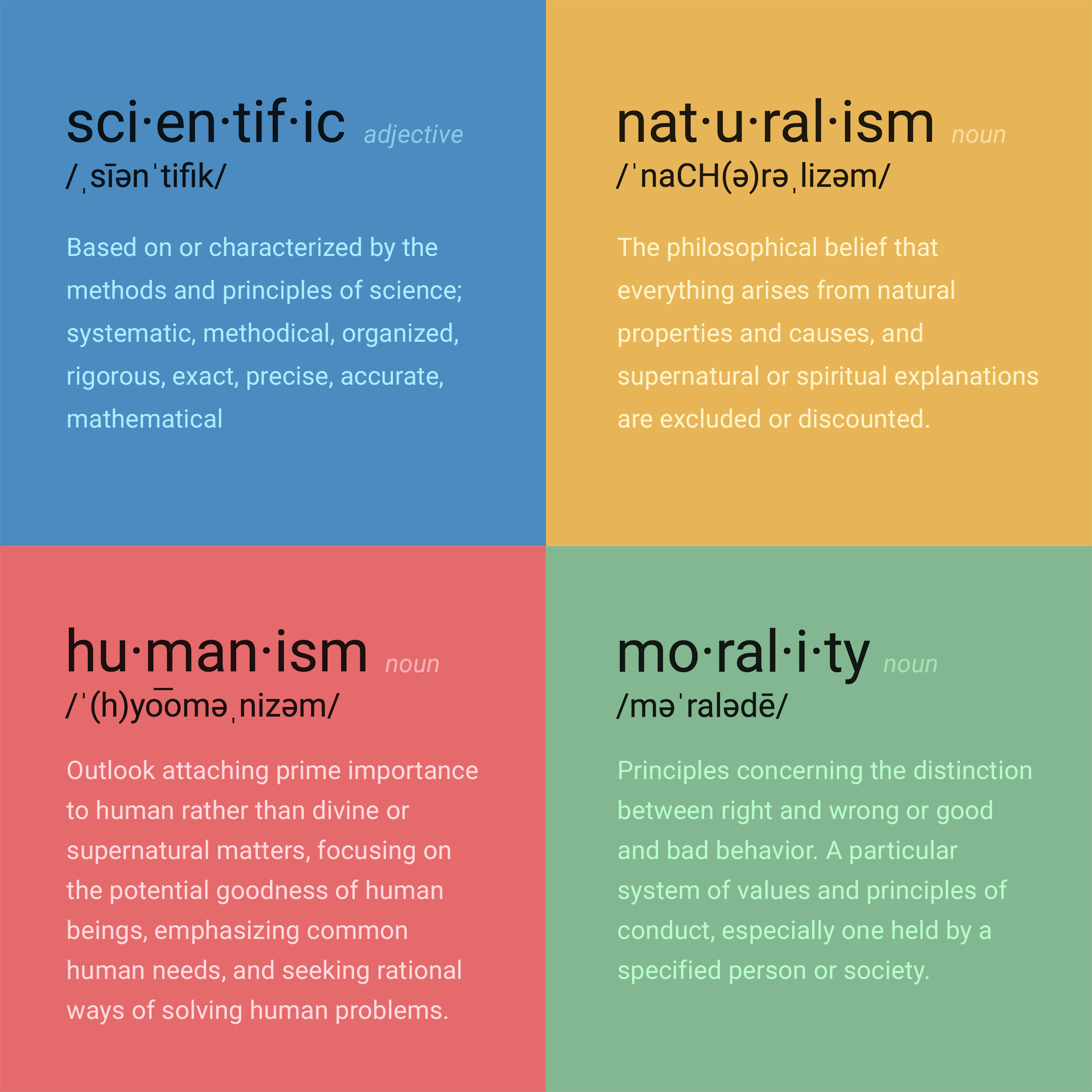

In response to my January, 2019 column (“Stein’s Law and Science’s Mission: The Case for Scientific Humanism”), California State University historian Richard Weikart, who is also a Senior Fellow of the Discovery Institute’s Center for Science and Culture (an Intelligent Design creationism advocacy organization), has written a critique in which he claims “Michael Shermer once again confuses science with atheism, and inexplicably claims that science can support humanism.” He says that I try “to rewrite history by insisting that science is built on atheist assumptions.” Even though I never mention atheism, in the following passage from my column Weikart says “scientific naturalism as defined here is atheism.” Judge for yourself:

Modern science arose in the 16th and 17th centuries following the Scientific Revolution and the adoption of scientific naturalism, or the belief that the world is governed by natural laws and forces that are knowable, that all phenomena are part of nature and can be explained by natural causes, and that human cognitive, social, and moral phenomena are no less a part of that comprehensible world.

Atheism is simply the lack of belief in a God. Full stop. It is not a worldview, paradigm, or ideology. Most atheists, of course, embrace scientific naturalism as I’ve defined it, but so do many modern theists such as the renowned geneticist and Director of the National Institutes of Health, Francis Collins, whom Weikart says would not accept “this atheistic definition of science.” On the contrary, I know Dr. Collins and include our dialogue on this very topic in my book The Believing Brain (2011, Henry Holt) in which he reiterates his rejection of Intelligent Design creationism (his book The Language of God is one of the best refutations of all forms of creationism) and affirms his commitment to scientific naturalism without an underlying atheist assumption. On the evolution of the moral sense, for example, Collins told me “that wouldn’t rule out that God planned it, since for a theistic evolutionist like myself, evolution was God’s awesome plan for all creation. If God’s plan could give rise to toenails and temporal lobes, why not also a moral sense?” As Collins defined it in a 2006 article in Nature titled “Building Bridges”, theistic evolution is the position that “evolution is real, but that it was set in motion by God.” […]