SCIENCE SALON # 53

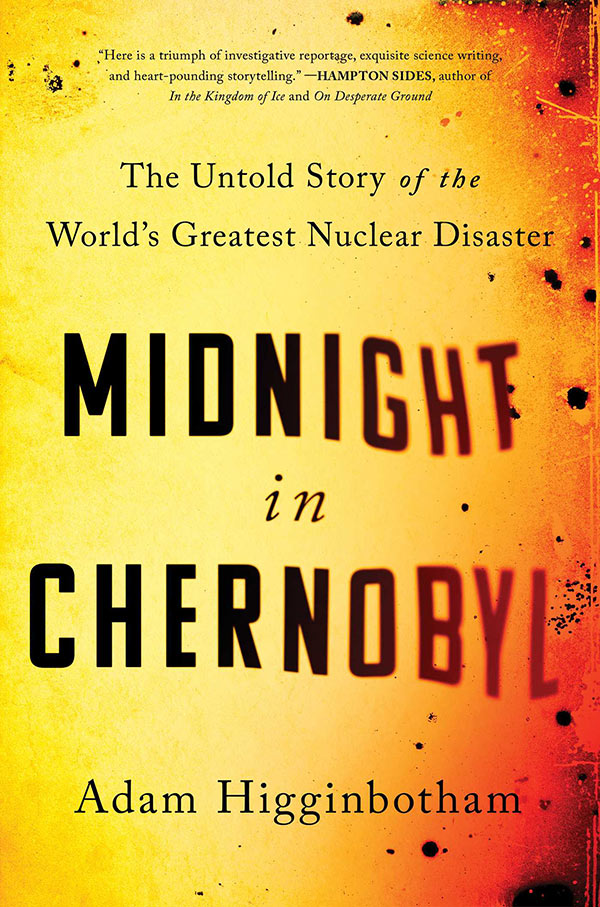

Adam Higginbotham — China Syndrome II: The True Story of What Happened at Chernobyl

In this discussion with the author of the newly published book Midnight in Chernobyl: The Untold Story of the World’s Greatest Nuclear Disaster, Adam Higginbotham tells what really happened at Chernobyl, by far the worst nuclear disaster in history, and why it took so long to discover what really happened. Human error and technological design flaws in the reactor are only proximate explanations for the core meltdown and explosion. The ultimate explanation is to be found in Soviet secrecy and lies. The book reads like an adventure novel, but it’s a richly researched non-fiction work by a brilliant storyteller. Don’t wait for the motion picture based on the book, which is years down the line. Get and read this gripping account to understand why people are still so afraid of nuclear power.

Adam Higginbotham was born in England in 1968. His narrative non-fiction and feature writing has appeared in magazines including GQ, The New Yorker and the The New York Times magazine. He is the author of A Thousand Pounds of Dynamite, named one of Amazon’s Best Books of 2014 and optioned as a film by Warner Brothers. He recently completed Midnight In Chernobyl: The Untold Story of the World’s Greatest Nuclear Disaster, which will be published in the US by Simon & Schuster on February 12th 2019. The former US correspondent for The Sunday Telegraph magazine and editor-in-chief of The Face, he lives with his family in New York City.

Listen to the podcast via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, iHeartRadio, and TuneIn.

This Science Salon was recorded on February 5, 2019.

Check Us Out On YouTube.

Science Salons • Michael Shermer

Skeptic Presents • All Videos

You play a vital part in our commitment to promote science and reason. If you enjoy the Science Salon Podcast, please show your support by making a donation.

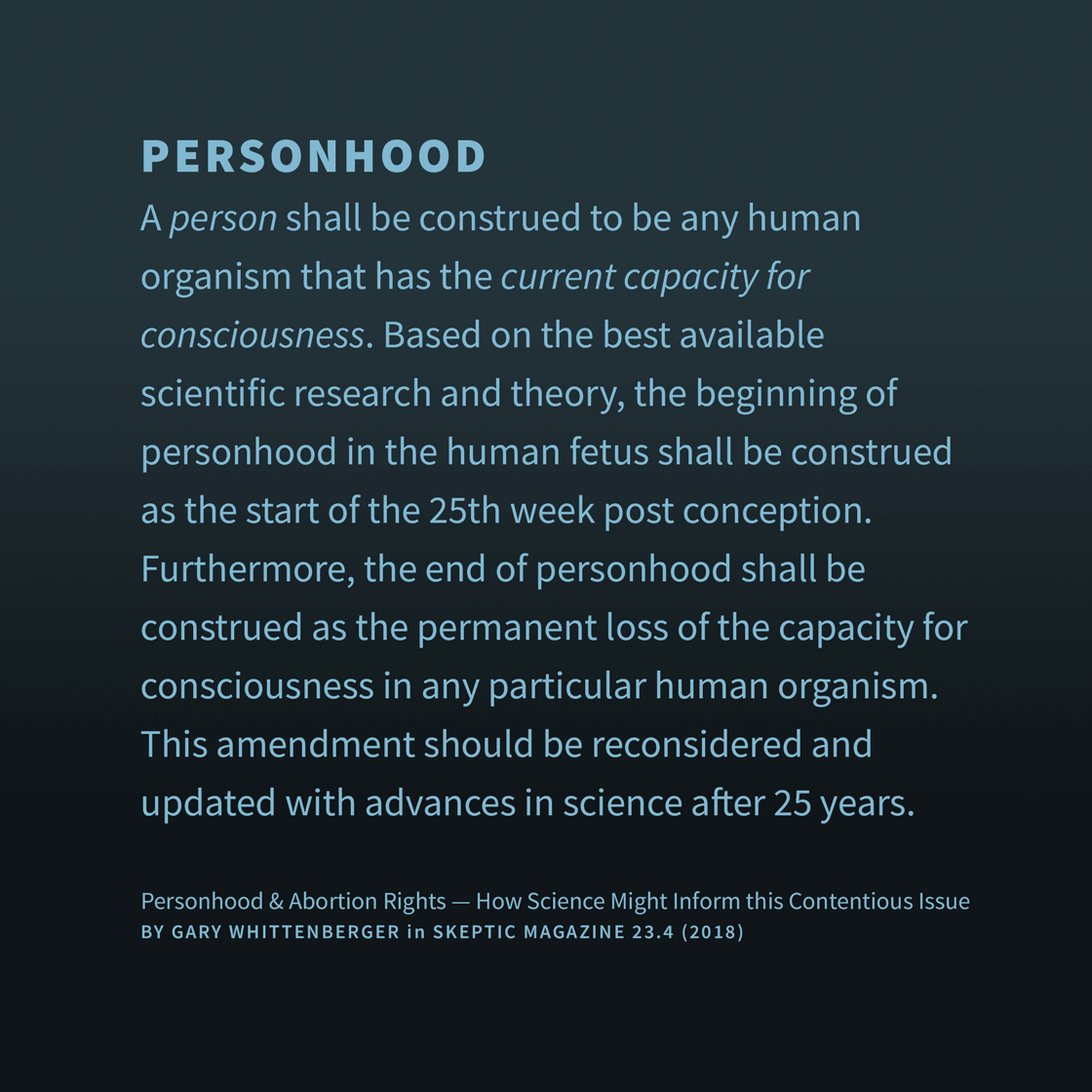

Although it’s been 45 years since Roe v. Wade, abortion continues to be a highly controversial and polarizing issue. In this essay, Gary Whittenberger articulates the philosophical and scientific foundation for a third option between the two extremes of pro-life and pro-choice — the pro-person position — after examining the evidence for the best possible answer to the question: “When does the human fetus acquire the capacity for consciousness?” This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 23.4 (2018).

Personhood & Abortion Rights

How Science Might Inform this Contentious Issue

Although it has been 45 years since Roe v. Wade was decided by the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS), abortion continues to be a highly controversial and polarizing issue within the body politic. At the two ends of the continuum are the radical pro-life and radical pro-choice advocates. The radical pro-life position is that from the moment of conception the human organism is a person that should have full human rights, including the right to life, and these rights should be fiercely protected by the state. On the other side, the radical pro-choice position is that the pregnant woman already has full human rights, including the right to bodily autonomy, and that she can freely decide to end her pregnancy at any time she wishes for any reason at all. Many pro-lifers view the zygote—the one-celled human organism resulting from fertilization—as sacred, and believe that causing the death of the zygote, embryo, or fetus, either directly or indirectly, is murder. By contrast, the pro-choicers believe that the organism becomes a person only after it leaves the womb and becomes disconnected from the life support of the mother. The main purpose of this essay is to articulate a third position that falls between these two extremes. Call it the “pro-person” position. Although it leans more towards the pro-choice stance, it has a much stronger philosophical and scientific foundation.

Most of us would agree that all persons should be assigned the full spectrum of human rights, e.g. rights to life, bodily autonomy, property, etc. But what is a person anyway? When does the human organism developing inside a woman become a person? Traditionally, the answer was left to theologians and religious leaders. The prevailing view during the time of Aristotle was that the human soul entered the forming body at 40 days in male embryos and at 90 days in female embryos.1 On the other hand, during medieval times theologians referencing Genesis concluded that the soul enters the body when the baby takes its first breath. Today, many religious people opine that “ensoulment” occurs at fertilization. As efforts to define, identify, or locate the soul have failed, and as religion has declined in its influence, different thinkers have simply pinned the beginning of personhood to different developmental milestones.

A human organism is not a person when it has never before or will never again possess the capacity for consciousness.

The most popular milestones have included: conception, first heart beat, quickening (fetal movement when first detected by the pregnant woman), onset of pain perception, first brain waves, first brain waves in the cerebral cortex, birth itself, and first breath. On May 4, 2018, the governor of Iowa signed into law a bill which bans most abortions once a fetal heartbeat is detected, occurring usually around six weeks of pregnancy.2 On the other hand, the decision in Roe v. Wade in 1973 accorded importance to fetal viability, but this has obvious drawbacks. Viability depends very much on modern medical technology and the skill of physicians and nurses. With the best of technology, a 20-week-old fetus may occasionally be kept alive, but without it even a 36-week-old fetus may perish. In the future it will probably become possible to sustain a human organism in a special artificial incubator from fertilization for a period of nine months, making viability a moot point. Personhood should not be defined by the fetus’ location, dependence, or connection to another human or to machines. Personhood should be defined by the species and the current capacities of the fetus.

Standard dictionary definitions of “person” are simplistic. Two relevant ones from Merriam-Webster are “human, individual” and “one (such as a human being, a partnership, or a corporation) that is recognized by law as the subject of rights and duties.”3 Three from Dictionary.com are “a human being, whether an adult or child,” “a self-conscious or rational being,” and “the body of a living human being.”4 And finally, the Oxford Living Dictionary defines a person as “a human being regarded as an individual.”5 Wikipedia provides more depth, defining “person” as “a being that has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established form of social relations such as kinship, ownership of property, or legal responsibility,” adding that the “defining features of personhood and consequently what makes a person count as a person differ widely among cultures and contexts.”6