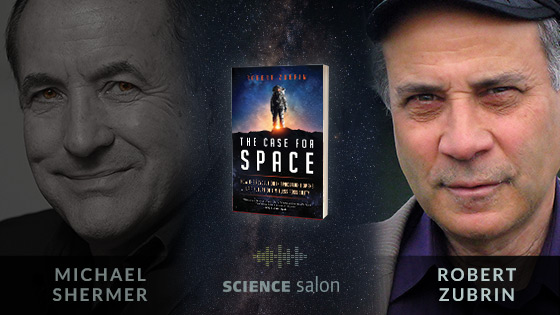

SCIENCE SALON # 72

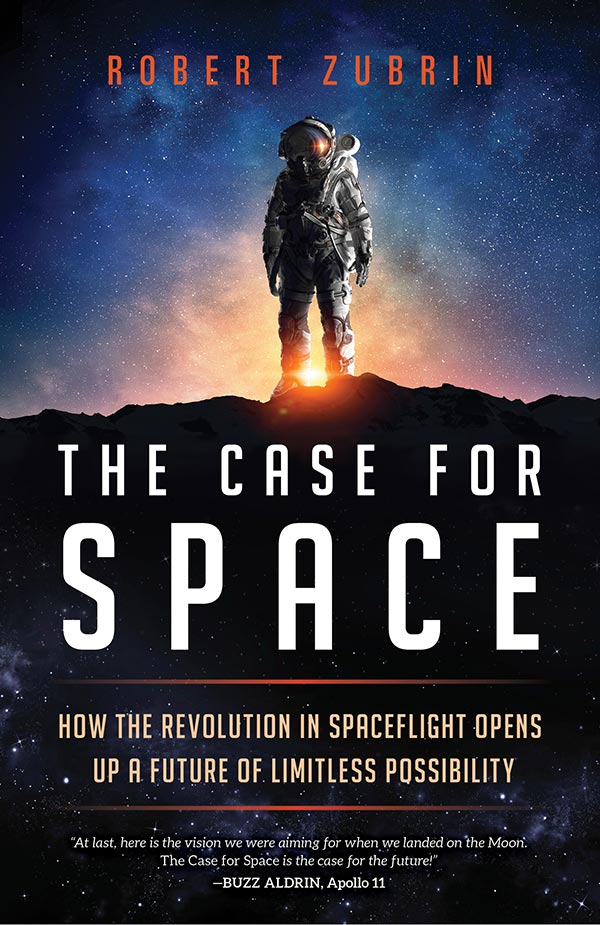

Robert Zubrin — The Case for Space: How the Revolution in Spaceflight Opens Up a Future of Limitless Possibility

In this dialogue, visionary astronautical engineer Robert Zubrin lays out the plans for how humans can become a space faring, multi-planetary civilization, starting with the competing entrepreneurs like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos who are creating a revolution in spaceflight that promises to transform the near future. Fueled by the combined expertise of the old aerospace industry and the talents of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, spaceflight is becoming cheaper. The new generation of space explorers has already achieved a major breakthrough by creating reusable rockets. Zubrin foresees more rapid innovation, including global travel from any point on Earth to another in an hour or less; orbital hotels; moon bases with incredible space observatories; human settlements on Mars, the asteroids, and the moons of the outer planets; and then, breaking all limits, pushing onward to the stars.

Zubrin shows how projects that sound like science fiction can actually become reality. But beyond the how, he makes an even more compelling case for why we need to do this—to increase our knowledge of the universe, to make unforeseen discoveries on new frontiers, to harness the natural resources of other planets, to safeguard Earth from stray asteroids, to ensure the future of humanity by expanding beyond its home base, and to protect us from being catastrophically set against each other by the false belief that there isn’t enough for all.

Zubrin and Shermer also discuss:

- what the Apollo program meant to Zubrin and to the current generation of space engineers and explorers

- the balance between government and private enterprise for the future of space exploration

- comparing future space explorers with past earth explorers

- why type of government should be established on Mars

- what if a tyrant takes over the Martian colony and controls the air?

- what type of new species we will become if we establish permanent civilizations on other planets and moons?

- is human progress inevitable?

- the role of freedom in human progress.

Listen to the podcast via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, iHeartRadio, and TuneIn.

This Science Salon was recorded on June 17, 2019.

Check Us Out On YouTube.

Science Salons • Michael Shermer

Skeptic Presents • All Videos

You play a vital part in our commitment to promote science and reason. If you enjoy the Science Salon Podcast, please show your support by making a donation.

Social psychologist Carol Tavris reminds us that justice requires us to assess the evidence, and that this requirement is especially imperative when public opinion and emotion are weighted heavily in favor of one side. This column appeared in Skeptic magazine 24.2 (2019). The illustration above is by Ástor Alexander.

The Sisyphean Challenges of Skepticism or, Start by Disbelieving

I recently received a message from a colleague asking me to sign a petition at change.org, protesting a grant of $400,000 awarded by the U.S. Department of Justice to the “Start by Believing” campaign. I hadn’t known about the grant, or for that matter about the campaign Start by Believing, which was launched by a group called “End Violence Against Women International” as a “global campaign transforming the way we respond to sexual assault.” And how should we respond to sexual assault? We must “Start By Believing” the victims—who, right off the bat, are to be called “victims” and not “complainants” or “accusers.”

In America, the End Violence Against Women campaign is part of an effort, on colleges and in courtrooms, to promote “victim-centered investigations.” The guidelines admonish investigators, among other things, to begin with an “initial presumption” of the accused’s guilt, to seek any information that will “corroborate the victim’s account,” and to make sure that the victim’s story does “not look like a consensual sexual experience.”1

Whether someone is a ‘victim’ is a conclusion to be reached at the end of a fair process, not an assumption to be made at the beginning.

Last year, a group of dozens of eminent law professors, including many who have been involved in Innocence Project exonerations, wrote an Open Letter protesting the dangerous bias introduced by the very idea of investigations that start out manipulating evidence to support the accuser.2 This may seem the best way to counteract the long legacy of investigations that have started out with a bias supporting prosecutors—especially in cases involving black men and women who have been raped—but it is doomed to backfire because it creates its own forms of injustice. The Open Letter cited District Court Judge F. Dennis Saylor, who wrote that we cannot automatically assume that someone is a “victim” in a legal matter because “[w]hether someone is a ‘victim’ is a conclusion to be reached at the end of a fair process, not an assumption to be made at the beginning.” An investigation is not a matter of “believing” or “disbelieving” an accusation; justice requires us to assess the evidence. And this requirement is especially imperative when public opinion and public emotion are weighted heavily in favor of one side. […]