In the following essay Dr. Michael Shermer considers the pitfalls of projecting the consequences of the pandemic for our future (the availability heuristic, the negativity bias, the difficulties of superforecasting, and the contingent nature of history) and with those caveats in mind he explores what might change in these areas of life: economics and business; marriage, dating, sex, and home life; entertainment, travel and vacations; education; politics and society; and personal and public health. Cautious optimism is proposed for our future.

Published in The American Scholar, August 31, 2020.

Image above by Ivan Radic (Flickr) (CC BY 2.0).

Read the essay below, or listen to Michael Shermer in Science Salon podcast # 149, introducing then reading a longer version of this essay. The reading of the essay begins at 8:47.

The After Time

The future of civilization after COVID-19

As I write on these late days of the summer of 2020, it often feels like our civilization has morphed into a Herman Melville novel in which …

All that most maddens and torments; all that stirs up the lees of things; all truth with malice in it; all that cracks the sinews and cakes the brain; all the subtle demonisms of life and thought; all evil, to crazy Ahab, were visibly personified, and made practically assailable in Moby Dick. He piled upon the whale’s white hump the sum of all the general rage and hate felt by his whole race from Adam down; and then, as if his chest had been a mortar, he burst his hot heart’s shell upon it.

Who would not be maddened and tormented by the images and stories coming out of intensive care units where COVID-19 patients gasp out their final breaths as loved ones watch remotely, unable even to bid a final farewell? Who hasn’t experienced cracked sinews and caked brains from months of being isolated with our thoughts, our voices masked, our social movements regulated?

As we peer into the distant horizon, the seeing becomes misty, clarity clouded in the fog of uncertainty. What will 2020 mean in 2030? Or 2050? Or 2120? Even that class of seer known as superforecasters, those trained in the dark arts of Bayesian reasoning and big-data analysis, do no better than chance when they look more than five years out. And I’m no superforecaster. Called upon to forecast the future of our civilization, I feel like Will and Ariel Durant, who in their short volume The Lessons of History (1968) began: “It is a precarious enterprise, and only a fool would try to compress a hundred centuries into a hundred pages of hazardous conclusions. We proceed.”

The Before Time and the After Time

In a 1966 episode of Star Trek titled “Miri,” the prepubescent heroine of the story explains to a flummoxed Captain Kirk what happened on her planet in which all the Grups (grownups) were dead, leaving the Onlies (children) to fend for themselves: “That was when they started to get sick in the Before Time. We hid, then they were gone.” According to linguist Ben Zimmer, who has traced the phrase’s etymology, the Before Time often represents a pre-plague world, and the expression has a literary history at least as old as the King James Bible, in which the author of the Book of Samuel writes: “Beforetime in Israel, when a man went to enquire of God, thus he spake, Come, and let us go to the seer: for he that is now called a Prophet was beforetime called a Seer.” The locution has been resurrected in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, as when Atlantic columnist Marina Koren wrote of “the exacerbated sense that the days before the coronavirus swept across the country—the ‘Before Time,’ as many have taken to calling it—feel like a bygone era.”

If there is a Before Time describing a pre-postapocalyptic world, there is also an After Time onto which we may prophesize what happens after the world ends. Although troubling times are often tagged apocalyptic, invoking the complete and final destruction of the world, the word’s original Greek meaning was “revelation,” or “an unveiling or unfolding of things not previously known and which could not be known apart from the unveiling.” It is in this sense that I want to turn toward what this period may unveil, if we can see through the barriers blocking prognostication. There is a reason why, as Yogi Berra quipped, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” I will mention four.

The first is the availability heuristic, which holds that we assign probabilities of potential outcomes based on examples that are immediately available to us, especially if they are emotionally salient and easy to visualize. Your estimation of the probability of dying in a plane crash, for example, will be directly related to your exposure to stories about air disasters. The second is the negativity bias that directs our attention to threats more than treats, negative stimuli more than positive. The third was identified by Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner in their 2015 book, Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction, in which most so-called experts were no better than dart-tossing monkeys when their predictions were checked. They were overconfident, encouraged by the lack of feedback on their accuracy (also known as confirmation bias), and, despite the scientific veneer, are victims of all the cognitive biases and illusions that plague the rest of us. The fourth, and arguably the biggest impediment to prediction, is that the world is highly contingent and chaotic, and at certain inflection points, the course of history can be nudged out of one pathway and into another by seemingly small and random events, but these are very difficult to predict.

The question is, are these factors distorting our evaluation of the events of 2020? Does the COVID-19 pandemic constitute a nudge sufficiently powerful to knock society into entirely new pathways, or will it be washed over by the tides of history as we continue on with business as usual?

Most salubrious changes in society come about incrementally through established institutions, not through violent revolution or disruptive upheavals of change. In my 2015 book, The Moral Arc, I tracked centuries of progress in domains ranging from politics to economics, civil rights to criminal justice, war to civility, governance to violent crime, with a number of stops along the way. In nearly every case, the evidence demonstrated that gradual, step-wise problem-solving is by far the most successful strategy in creating a safer and more equitable society. Will that trend continue through this pandemic and into a post-COVID-19 world? Let’s consider the possibilities. […]

SCIENCE SALON # 131

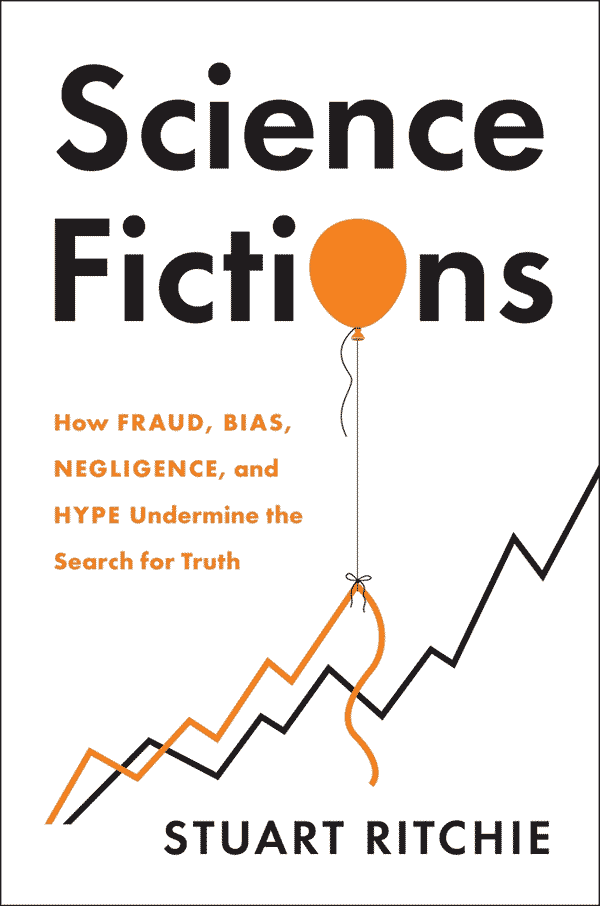

Michael Shermer with Stuart Ritchie — Science Fictions: How Fraud, Bias, Negligence, and Hype Undermine the Search for Truth

Science is how we understand the world. Yet failures in peer review and mistakes in statistics have rendered a shocking number of scientific studies useless — or, worse, badly misleading. Such errors have distorted our knowledge in fields as wide-ranging as medicine, physics, nutrition, education, genetics, economics, and the search for extraterrestrial life. As Science Fictions makes clear, the current system of research funding and publication not only fails to safeguard us from blunders but actively encourages bad science — with sometimes deadly consequences. Yet Science Fictions is far from a counsel of despair. Rather, it’s a defense of the scientific method against the pressures and perverse incentives that lead scientists to bend the rules. By illustrating the many ways that scientists go wrong, Ritchie gives us the knowledge we need to spot dubious research and points the way to reforms that could make science trustworthy once again. Shermer and Ritchie also discuss:

- why we need to get science right because science deniers will pounce on such fraud, bias, negligence, and hype in science,

- Daryl Bem’s ESP research and what was wrong with it,

- “psychological priming” and the problem of replication,

- sleep research and the problems in Matthew Walker’s book Why We Sleep,

- Amy Cuddy and the problem with “Power Posture” research,

- Andrew Wakefield and the biggest fraud in the history of science linking vaccines & autism,

- diet and nutrition research and the complication of linking saturated fats, unsaturated fats, cholesterol, and heart disease,

- Phil Zimbardo‘s Stanford Prison Experiment,

- Samuel Morton’s skulls showing racial differences in head size, Steve Gould’s critique, the critique of Gould, and the critique of the critics of Gould,

- self-plagiarism,

- p values / p hacking

- the Schizophrenia/amyloid cascade hypothesis and why it has been hard to prove,

- the file-drawer problem,

- how to detect fraud, and

- Terror Management Theory and why it is almost certainly wrong.

Stuart Ritchie is a lecturer in the Social, Genetic and Developmental Psychiatry Centre at King’s College London. His main research focus is human intelligence: how it relates to the brain, how much it’s affected by genetics, and how much it can be improved by factors such as education. He is a noted supporter of the Open Science movement, and has worked on tools to reform scientific practice and help scientists become more transparent when reporting their results.

Listen to the podcast via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, iHeartRadio, and TuneIn.

You play a vital part in our commitment to promoting science and reason. If you enjoy the Science Salon Podcast, please show your support.