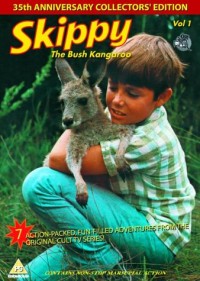

Giving Skippy human like expressions and agency was more fantasy than fact.

If you’re over the age of thirty and grew up in Australia, there’s a good chance you know who Skippy is. This famous kangaroo—a friend ever true—was the Aussie equivalent of Lassie, forever helping her human companion, Sonny Hammond, get in and out of trouble.

With their upright stance and small hands, kangaroos are readily anthropomorphised. That is to say, it’s easy to attribute kangaroos with human-like traits. Just recently, a heart-breaking story of a kangaroo mourning a lost companion did the rounds through Australian social media. Photographer Evan Switzer chanced upon a dying female kangaroo being cradled in the forearms of a male, a small joey standing nearby.

“He would lift her up and she wouldn’t stand she’d just fall to the ground, he’d nudge her, stand besides her…it was a pretty special thing, he was just mourning the loss of his mate,” Evan was reported saying in the Daily Mail.

Only the kangaroo wasn’t mourning for its departed mate. It was…well, for a lack of a better term, turned on. Sexually. And might have even been the murderer.

To be fair, while probably more accurate than a kangaroo funeral, such a poetic description itself falls foul of anthropomorphising the situation. Mourning, desiring, murdering … all of these things are relatable given human experience and storytelling. There are connotations we add to these words that imply characteristics unlikely to be experienced by kangaroos, such as agency and social emotions.

A far more appropriate description of the scene robs it of love, hatred, compassion, or lust.

Sydney University senior lecturer in veterinary pathology Dr Derek Spielman told the Australian Guardian, “Pursuit of these females by males can be persistent and very aggressive to the point where they can kill the female. That is not their intention but that unfortunately can be the result, so interpreting the male’s actions as being based on care for the welfare of the female or the joey is a gross misunderstanding, so much so that the male might have actually caused the death of the female.”

Evan’s error was a simple one, and one we all make. Our brains evolved to be social organs; just as we see faces in clouds, seeing a death scene as a lover is cradled in the arms of a sad-looking boomer is a natural effect of social wiring.

That isn’t to say we’re always wrong in our interpretation of animal behaviours. Adult cats have learned to vocalise for humans, for instance, having learned to manipulate our tendency to associate sounds with speech. The domestication of dogs has also enhanced human traits, such as using eye contact to communicate.

Yet determining what is our social bias and what is a legitimate reflection of a human-like experience or behaviour is challenging, and requires precise, objective language. Pain is a word that carries a great deal of cultural baggage. For humans, the experience of pain is more than a neurological response accompanied by a flood of stress hormones. It involves temporal awareness, self-awareness, a concept of damage. It might not be a great stretch to imagine another great ape experiencing human-like pain, but what of a mouse? A fish? A lobster? A fly?

Given decisions we make on the ethical treatment of animals in our care, such as culling back kangaroo populations near and within urban areas, accurately understanding their behaviour and experiences on their own terms is important. As is knowing what our own cultural values are when it comes to animals being animals, and not people.

As for Skippy, she’ll always have a special place in Australian’s hearts as the world’s most intelligent marsupial.

Worrying about what animals feel is a bit presumptuous, considering we have yet to agree on and consistently apply a standard of how we relate to our fellow humans. We’ve generated a lot of words on the subject over the last few millenia, but we continue to treat each other like animals whenever it is profitable, ideologically expedient, or personally convenient. Perhaps we should get our own ethical house sufficiently in order before we feel comfortable deciding who to invite in as guests.

I have worked with elephants, but I do not apply feelings to them that cannot be observed directly. I know that I loved the elephants I cared for and they demonstrated that they had a strong social bond with me. I cannot call their bond love as I just do not know.

I also cannot tell for certain when two people love each other. How can we attribute feelings to animals that are even difficult to assess in people?

Despite watching Skippy in my formative years, I cannot say that I know enough about kangaroos – or wallabys – to be able to say whether or not they experience grief. But I’m quite certain that elephants do. Also dogs and horses. People who say that no animals have feelings cannot have known dogs. Or horses. Or elephants. I haven’t known any elephants either, come to that, but it’s amazing what one can learn by paying close attention to Sir David Attenborough. I’m not saying that animals experience emotions the same way I do. But they do have feelings. More, in fact, than some people I’ve met.

Obviously, this author and those criticizing “anthropomorphism” have failed to accept evolution as a scientific fact. We are animals, period. Evolution and even simple observation would tell us we share vast physical commonalities. To argue that our brains, the presumed center of our emotions and reasoning, and too a physical commonality, are or can be an exception is absurd in its face.

“Anthropomorphism” is a “God of the gaps” used to create distinctions where little or no differences exist.

“…the vet’s interpretation is no better than anyone else’s…” Really? Years of study of veterinary science versus say a car mechanic?

Anthropomorphism is a terribly misused word, invented to appropriate as uniquely human a wide spectrum of mental states which are likely to be shared by most mammals and probably most vertebrates. The motive is fairly transparent – minimising the sentience and pain sensitivity of other animals legitimises their exploitation. This why we should exercise extreme caution in using it. Anthropomorphism should only describe behaviours that truly are exclusive to humans – language for example, or driving a car or wearing clothes. Many non-verbal mental states, especially emotions (including social emotions), pain, and even memories, cause-and-effect reasoning, anticipation and future prediction, are likely to be widely shared in the vertebrate world. This should not be a surprise as vertebrate neurophysiology, endocrinology and common evolutionary heritage all suggest common functionality. Darwin concluded as much and most scientists who closely study mammal and bird behaviour reach similar conclusions. It is hubris to assume that, because we are the only animals who verbalise our mental states, we are therefore the only ones who experience them. The null hypothesis in interpreting animal behaviour should be that, unless there is good evidence to the contrary, the non-verbal mental states of most vertebrates are likely to be similar. The word anthropomorphism, carelessly deployed, reverses that assumption and harks back to the pre-Darwinian era of Cartesian dualism where other animals were seen as unfeeling machines. In the example given, it is not unreasonable to interpret the kangaroo behaviour as affectionate, though the violent rapist interpretation could be correct too. Did anyone actually record the events that preceded the Youtube clip? If not, the vet’s interpretation is no better than anyone else’s – perhaps even more suspect, given that vets’ employers are, in the main, the animal exploitation industries.

I agree. It also should be said that just because an animal’s response to death may be something we would consider inappropriate for humans, this doesn’t mean that the animal isn’t also experiencing and processing grief by their behaviors. For example, cannibalism or even sexual behaviors are often natural responses to death for some animals, and I can’t help but attribute it to mourning when I see it in action. Those feelings and behaviors could both be vital to an animal’s survival.

And NZ. The signature tune is burned into my brain.

Everyone over 30 who grew up here in Norway also grew up with Skippy – and Flipper :)

the Netherlands: Skippy & Flipper…

Anthropomorphism is an interesting word… The word seems to justify and allow a system of oppression, destruction and torture of nonhuman animals. Simply because we humans as the most powerful animals have decided our form of “intelligence” and “emotions” are superior, we then decided that all other animals are ours to use as we please. Carnism is the unspoken and unconscious system we are born into and fail to question at the earth’s paril.

Thanks for the comment, Aaron. The caution against anthropomorphising animals can go both ways; all too often, we attribute behaviours that are seen as positive in humans which are signs of fear, anxiety, or stress in animals. Smiling chimpanzees is a classic example, where we see joy in their fear and submission. Holding a value in the lives of animals and not wanting them to suffer for food or entertainment is laudable, and one I support. But personally, I wouldn’t want this value to be based on false assumptions of human-like agency or emotions, but rather on my own humanity and a desire to limit unnecessary pain and stress no matter how dissimilar an animal is to me.

The idea that an ox’s tongue exists for the sake of being eaten, rather than for the sake of eating, is a vain anthropocentric misconception born out of an insensitivity similar to the aftertaste this article has left.

Anthropomorphism can go both ways, but that doesn’t mean those ways are morally equal. To anthropomorphize an animal can be entertaining, and since entertainment is a valuable resource, anthropomorphism can be a tool for manipulating, especially immature, humans. All in fun…

On the other extreme, perceiving non-human life to be so unlike us as to disregard observations of social passion is anthropocentric and, I think, the same impulse in humans that leads to genocide via the ideological dehumanization of others humans. That first step is thinking yourself to be of some superior sort – the rest just happens.

Thank you Mike for such a considered and open response. I agree that misattribution of emotional meaning is all too common cross species and interspecies as well. Even in the example of smiling there is the reality that in human animals a smile can indicate submission and fear. Our pattern seeking drive will often cause such attribution errors. More directly, I am speaking to the concept of Anthropocentrism. This is the worldview that puts humans at the center of everything. This tendency in human animals can lead to error. Thanks again for your time.