A modern newsroom in Berlin. By Thomas Schmidt (NetAction) via Wikimedia Commons.

I’ve long advocated the construction of customized online tools (websites, apps and more) to advance the cause of skepticism. In the last two years I’ve noticed a distinct trend where these tools are in being built in increasing numbers—but not just by skeptics! One major source of these tools might surprise you: the newspaper industry.

I only got actively involved in skepticism about seven years ago. At that time programmable web services were just becoming all the rage—something the industry was calling Web 2.0. This includes social media and other sites which provide simple tools like maps, weather and other data.

What distinguishes Web 2.0 from what came before is these sites expose their technology not just as human-readable pages, but also as computer-friendly APIs (application programming interfaces). This allows other websites and apps to be built using the other services as building blocks. So for example, to build their fantastic interactive vaccine outbreak map, the Council of Foreign Relations relied on open technology provided by OpenStreetmap. This allowed them to focus on the task at hand (visualizing a global vaccine problem) instead of solving more basic problems (web-based mapping).

As this is closely related to my career expertise, I decided to focus in on this technology and how it could be applied to skepticism. This was the topic of the first presentation I gave at a skeptic conference—a paper presentation at The Amazing Meeting 6 called Building Internet Tools for Skeptics. This is also the stated topic area of my personal blog Skeptical Software Tools, which I launched at the same time as a place to discuss that presentation.

In my experience, skeptic conferences are thick with attendees who work in computer-related fields. I was betting that some of these skeptics would be interested in applying their skills to advancing skepticism online. Many already have blogs, podcasts or social media feeds, but I was looking to encourage the creation of more interactive online tools that might be used by skeptics and the general public. Some of these require significant programming and administration, but others can be easily assembled using off-the-shelf tools.

And indeed, in the years since we’ve seen the creation of a number of electronic tools that are specifically created to assist skeptics and other critical thinkers. Australian skeptic Joel Birch created a WordPress plugin called Nofollowr to help skeptic bloggers link to sites they are criticizing without boosting them in Google. American skeptic Shane Brady created an interactive database of skeptical podcasts called Skeptunes (that he says was inspired in part by me). There are also now a number of Smartphone applications for skeptics including ones from the Skeptic’s Dictionary, the climate science site Skeptical Science and others. And that is just a sampling.

Other tools that skeptics find useful have been built by people who come from the high tech industry. Most of these tools found an audience with skeptics after the fact. The rebuttal linking tool RBUTR was built by two Australian high tech entrepreneurs to make it easier to find material on both sides of controversial topics. After it was created they reached out to skeptics to promote their tool and encourage its use, in presentations at The Amazing Meeting and other events.

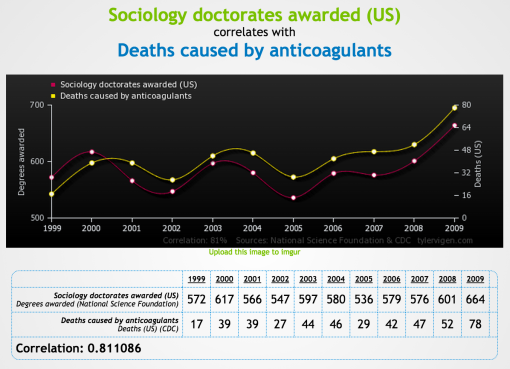

A terrific online tool called Spurious Correlations vividly demonstrates the post hoc ergo propter hoc logical fallacy by drawing graphs correlating clearly unrelated data from public data sets. Its creator Tyler Vigen told me via email he’s never identified as a skeptic, but just saw an interesting opportunity for public education.

An example from Spurious Correlations – “Sociology doctorates awarded (US) correlates with Deaths caused by anticoagulants” vividly demonstrates that correlation does not equal causation.

We need online tools against bunk now more than ever. With the rise of social media (Twitter, Facebook et al.) there is an ever increasing ability for falsehoods such as rumors, hoaxes and misinformation to spread rapidly online. Many of these relate to news or political issues that may not directly concern some skeptics. But some clearly do, such as the recent spate of false or pseudoscientific information about Ebola. The size of the Internet allows this problem to scale exponentially, so we need tools to combat it which can also scale.

This of course has not gone unnoticed in other circles, including the newspaper industry. As their business models have been disrupted by the Internet they’ve been forced to cut budgets, hurting things like investigative reporting and remote bureaus. It has also forced them in some cases to rely on citizen journalism posted on social media for initial reports of breaking news. This of course poses a huge issue with credibility—how do you validate a piece of video or a Twitter report from a faraway country? And what if your budget for fact checkers has also been cut?

And so we’ve seen the development of independent fact-checking organizations such as Politifact and FactCheck. There are as many as 89 of these organizations world-wide, according to a recent survey. While the facts they check are often in the political realm, they’ve normalized ideas such as external fact checking, crowdsourced fact checking and debunking bad information. This goes right to the core mission of skepticism.

Facing a huge load of work, these fact checkers have adopted new electronic methods including online research, custom software and crowdsourcing. At the same time, the newspaper industry has been looking for ways to evolve their business to replace the loss of traditional revenue and adapt to the digital world. In some newsrooms this has resulted in the hiring of “news developers”—technologists who work alongside journalists to create applications and interactive features for online news. Increasingly some of these news developers turn their eye toward the problem of fact checking, online misinformation, rumors and hoaxes, and the result is often a tool that is useful for skeptics as well.

Let me highlight two such tools that have recently emerged. One is called WikiWash, and is simply a more attractive interface to the revision history feature of Wikipedia. News events are often recorded quite quickly in Wikipedia articles, but these rapid edits can be a source of bias or spin if not scrutinized. WikiWash allows easy WYSIWIG browsing of recent edits to any article to make such scrutiny easier. WikiWash was built by The Working Group in conjunction with Metro News and the Center for Investigative Reporting, and is free for anyone to use. It is also open-source—the code is freely available to anyone who wants to launch their own version, identical or modified.

The other tool targets those viral social media rumors I mentioned earlier. Called Emergent.info, it was created by a team led by Craig Silverman, a Fellow of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia. It tracks viral stories and hoaxes that have gotten coverage in mainstream online news sources, and records whether the stories have been confirmed or debunked. Interestingly, it also tracks how many times the original and the debunk have been shared on social media. This is a very interesting glimpse into whether debunking bad information can outpace the information itself.

Emergent.info scoreboard tracking the spread of a recent claim that the president of Argentina became the adopted godmother of a boy to help stop him from becoming a werewolf. As you can see the original stories were shared far more than the debunks.

These are just two of many tools I’ve observed being built by newspaper-affiliated organizations. Many (including both of these) are available free for anyone to use, having been supported by charitable institutions for the benefit of the industry as a whole. I encourage skeptics to make liberal use of them in our battle against bad information online.

Further, it behooves us to observe and support the various news media nonprofits that support the development of these tools. Aside from the Tow Center and the Center for Investigative Reporting already mentioned, other supporting organizations include the Knight Foundation, the Nieman Lab and the Knight-Mozilla OpenNews project. One of these organizations may be the source of your next new favorite debunking tool!

And the updates continue: I blogged today at my personal blog Skeptools about three new fact checking websites that are useful to skeptics.

And the trend continues: the day after this posted, the Knight Foundation announced a round of funding of small projects, and sure enough one of them is a fact checking browser plugin.

Have you seen bellingcat?

https://www.bellingcat.com

It lets the public analyze “open source intelligence” like YouTube videos and photos to do things like track Russian weapons in Ukraine and debunk photoshopped images.

Yes! Bellingcat is an excellent additional example.