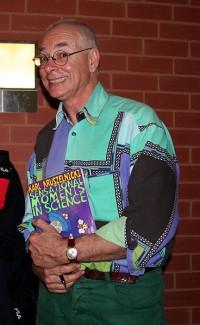

Karl Kruszelnicki at a University of Sydney event in 2006. Image by Enoch Lau, via Wikimedia Commons. Used under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

On the back of a book I wrote a few years ago is a blurb describing me as “the next generation Dr Karl”. Flattering, but I really hate that comparison. Not because I hate Dr Karl—who happens to be fantastic promoter of science—but because if it’s one thing the world doesn’t need, it’s one more wacky science communicator in a bright Hawaiian shirt.

Publishers love a hook for the reader. And since Dr Karl Kruszelnicki is arguably Australia’s most recognisable science writer, it makes sense that his name would be used to promote a science book written by a nobody like me.

I had the pleasure of interviewing Dr Karl for Skepticality in 2008, and have spoken to him once or twice since. His personality is as bright as his wardrobe, and if you have a science question he’ll undoubtedly have a quirky, fascinating story to respond with. (He’s especially generous about answering questions on Twitter.) He certainly presents a lot for a science personality to aspire to, and I have much admiration for the man.

Beyond sharing a love of science story-telling, though, our similarities are few. I wouldn’t be caught dead in a colour brighter than khaki green. I have piercings and a few tattoos, and usually take great pains to avoid describing myself as geeky. I also do my best to correct anybody giving me a PhD (one I never earned), and I don’t call myself a scientist since I haven’t run an assay or poked at a patient in years. Dr Karl I ain’t.

Before Dr Karl there was Professor Julius Sumner Miller. If you’re Australian, you’re either too young to remember him, old enough to recall him as the science teacher on the Cadbury’s chocolate commercials, or of the generation who watched his classic television show and recall his famous “Why is it so?” catch phrase. Thick glasses, crazy hair with a stiff collared shirt, his brand of science communication reflected the mid-20th century cliché of a scientist. The good professor’s legacy lives on in the title of a science outreach position at the University of Sydney—one held currently by Dr Karl himself.

Julius was from an era when science was stereotyped in lab coats, glassware and Bohr’s classic model of the atom. The representation evolved through the 1980s with the goal of reaching a new generation of young minds, giving us the likes of Bill Nye the Science Guy. Today’s colourful science communicator has itself become as cliché as the aged, craze-haired gentleman it replaced. Colourful bow-ties, loud shirts, comedic anecdotes abound as a technicolor contrast to the stiff, dusty old black-and-white scientists of yesteryear.

It’s easy to reason that this change in presentation is intended to appeal to that nebulous beast the “general public” by making the aloof, gibbering professor seem more accessible to Joe Average (not to mention to appeal to younger generations). However, it presumes the public is homogeneous enough to largely identify with such colorful characters.

A stark example is Dr Matt Taylor, the ESA scientist who recently became more famous for his “sexy girl” shirt than the Rosetta mission he was discussing. While it could be argued the controversy drew extra attention to the mission, it clearly polarised audiences on just what values this particular scientist represented. For many folk, he was not their kind of people. Given enough representations of this nature, it’s not hard to see why some demographics may distant themselves from what they perceive as a scientific culture dominated by geeks in loud shirts. As a culture, science just doesn’t speak for them.

Humans are inherently political animals. Far from rational machines, we tend to evaluate ideas more readily on our empathy with the messenger than we do the validity of the message. There are undoubtedly many people who adore the vibrant scientist with cartoonish expressions and rapid-fire narratives, which is great. Given the diversity of cultural identities in our community, however, we suffer when scientists become a caricature thanks to an over-abundance of bow ties, colourful shirts and larger-than-life personalities.

In 2006 I was fortunate enough to be paid to travel the breadth of the nation to perform science shows. We were literally described as a circus, and toured regional towns and cities in a colourful truck while wearing bright clothes, promising to make science “fun” for the average punter. If it was one thing I learned from the experience was that this was low hanging fruit. Science is easy to make fun with a few explosions and colour changing reactions. What is challenging is communicating the philosophy of science. Or even worse, gaining the trust of those who find certain fields of science clash with their world views.

So no, I really don’t want to be the next generation Dr Karl, thank you. I’m grateful we already have one of him. And this isn’t to say we don’t have diversity. Aging rock stars like Brian Cox and Brian May stand as clear counters to the stereotype. I welcome the next generation of science story tellers to continue to be from a great diversity of backgrounds in the hope we can connect with as many parts of the community as possible.

Insightful article; thanks, Mike!

When Curiosity landed on Mars, the two NASA stars were the “Elvis guy” Adam Steltzner and the “Mohawk guy” Bobak Ferdowsi. Turns out the Mohawk was the style the team picked for the guy to wear for that particular mission. I don’t know the story behind Dr. Matt Taylor’s shirt.

I watched an old episode of Bill Nye the Science Guy, and boy was it annoying with all those cuts and repetitions, like it’s for kids with ADD. I guess he was ahead of his time, because popular YouTube videos are even more annoying.