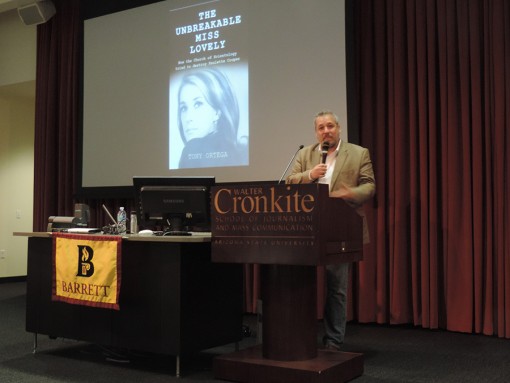

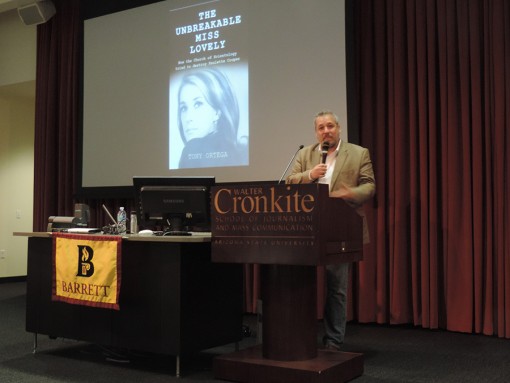

(Photo credit: Jim Veihdeffer)

Tony Ortega returned to his former stomping grounds in Phoenix on his book tour for The Unbreakable Miss Lovely: How the Church of Scientology Tried to Destroy Paulette Cooper (see my review in eSkeptic) on September 15. Tony’s talk, sponsored by the Barrett Honors College Downtown Campus and held at the Walter Cronkite Theater, recounted his personal story of starting in journalism in the city where L. Ron Hubbard developed Scientology, and how he came to write about Scientology after first seeing their involvement in a lawsuit against then-Phoenix-based cult deprogrammer Rick Ross (see, for example, Tony’s December 19, 1996 New Times story, “What’s $2.995 Million Between Former Enemies?”). One story led to another, and further opportunities to write about Scientology arose after he moved to Los Angeles to write for New Times L.A.

New Times eventually acquired the Village Voice. Tony became its editor in 2007 and brought with him experience in bringing stories to an online format. His first foray into daily-updated content for the Voice was to pore through the archives and reprint interesting stories from the past, which he enjoyed but did not attract much readership. When he started writing daily about Scientology in 2011, however, readership exploded. He has written on the topic every day since then, first at the Voice and, beginning in late 2012, at his own blog, the Underground Bunker, where he has broken numerous stories about the Church of Scientology as it has continued to lose long-time members and leaders.

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Jim Lippard is a long-time skeptic who works in the information security field. He founded the Phoenix Skeptics in 1985, and has contributed to Skeptic, Reports of the National Center for Science Education, Skeptical Briefs, The Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation, Joe Nickell’s book Psychic Sleuths, and Gordon Stein’s Encyclopedia of the Paranormal. Read Jim’s full bio or his other posts on this blog.

Former President Nelson Mandela of South Africa met with US President George W. Bush in the Oval Office in 2005—and yet, according to some people’s memories, Mandela died two decades earlier. (White House photo by Eric Draper)

At Chapman University I teach an undergraduate course called Skepticism 101: How to Think Like a Scientist. One of the course requirements is that each student must do an 18-minute TED-style talk. It’s a good exercise in learning to give public talks, as well as organize your thoughts in a manner conducive to both critical thinking and clear communication. The first student TED talk was by Taryn Honeysett on something called “The Mandela Effect,” of which I was unfamiliar. The name comes from the mistaken belief that the great statesman and civil rights activist Nelson Mandela (1918–2013) died while in prison in the 1980s, and it is characterized by a group of people who all misremember something in a similar manner.

The effect gained a cultural toehold in an Internet forum discussion over the proper spelling of a popular children’s book and television series called The Berenstain Bears, when a number of people insisted the correct spelling was Berenstein. (The series began in 1962, with the first book edited and published by Dr. Seuss—aka Ted Seuss Geisel.) Other examples of The Mandela Effect involve the number of states in the United States (50 or 52, with a sizable number of people believing it is 52, probably mixing states in the U.S. with cards in a deck), the correct spelling of the word definitely (or definitly), and people’s recall of what Darth Vader said in Star Wars: “Luke, I’m your father” or “No, I’m your father” (it’s the latter, although I too remember it by the more effecting version that addresses the subject).

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Dr. Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, a monthly columnist for Scientific American, an Adjunct Professor at Claremont Graduate University and Chapman University, and the author of The Believing Brain, Why People Believe Weird Things, Why Darwin Matters, The Mind of the Market, How We Believe, and The Science of Good and Evil. His new book is The Moral Arc: How Science and Reason Lead Humanity Toward Truth, Justice, and Freedom. Read Michael’s other posts on this blog.

If my explorations of skeptical history have revealed an overall theme, it is that things don’t change that much. Always there are scoundrels, scams, and misapprehensions; always there are those who probe mysteries and push back against paranormal fraud. Throughout history, those skeptics have repeatedly reached for the same tactics, claimed the same (scant few) rewards, and faced the same challenges of burnout and cynicism.

Astronomer Richard Anthony Proctor. For general details about Proctor’s life and career, read this brief biographical sketch published in 1874.

English astronomer and science popularizer Richard Anthony Proctor (1837–1888) makes an interesting case study. He weighed in as a skeptic against (surprisingly popular) Flat Earth advocates (see Junior Skeptic 53), quackery, and a range of pseudoscientific ideas connected to astronomy. His debunking book Myths and Marvels of Astronomy was a 19th century version of Phil Plait’s Bad Astronomy. Originally published in 1877 (my copy dates to 1880), Myths and Marvels of Astronomy is available to read for free in several editions online.

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Daniel Loxton is the Editor of INSIGHT at Skeptic.com and of Junior Skeptic, the 10-page kids’ science section bound within Skeptic magazine. Daniel has been an avid follower of the paranormal literature since childhood, and of the skeptical literature since his youth. He is also an award-winning author. Read Daniel’s full bio or his other posts on this blog.

How did the traditional character of the cannibal ogress Dzunuk’wa come to be claimed by cryptozoologists as a depiction of their hypothesized “Bigfoot” cryptid species? (Kwakwaka’wakw heraldic pole. Carved in 1953 by Mungo Martin, David Martin, and Mildred Hunt. Thunderbird Park at the Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria. Photograph by Daniel Loxton)

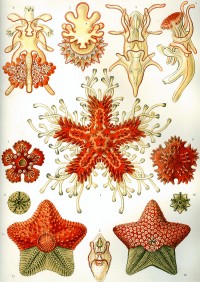

Much of my skeptical research traces the historical pathways through which pseudoscientific and paranormal beliefs emerge and evolve over time. In particular, I’ve explored the cultural origins of allegedly genuine monsters such as Bigfoot (“cryptids”) for

Junior Skeptic (the children’s section of

Skeptic magazine) and

Abominable Science!, my 2013 book with Donald Prothero.

My research has often led me to consider how folkloric phenomena are brought under the umbrella of cryptozoology (the largely pseudoscientific “study” of legendary, allegedly “hidden” animals). In this active process, fuzzy abstractions—fluid supernatural conceptions, diverse “saw something weird” events, stories, metaphors, and shifting myths—are distilled down into more-or-less concrete hypothetical “species” of cryptids. For want of a better term, I’ve started to think of this cultural crystallization process as “cryptozoologification.”1 And it’s a bit of a problem. When the mists of folklore are reified as the discrete objects of cryptozoological pursuit, something is not only lost, but actively discarded.

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Daniel Loxton is the Editor of INSIGHT at Skeptic.com and of Junior Skeptic, the 10-page kids’ science section bound within Skeptic magazine. Daniel has been an avid follower of the paranormal literature since childhood, and of the skeptical literature since his youth. He is also an award-winning author. Read Daniel’s full bio or his other posts on this blog.

A few months ago I wrote about the psychology of vaccine denial. In the post I discussed two publications, one of which (Nyhan, et al.) found:

Corrective information reduced misperceptions about the vaccine/autism link but nonetheless decreased intent to vaccinate among parents who had the least favorable attitudes toward vaccines. Moreover, images of children who have MMR and a narrative about a child who had measles actually increased beliefs in serious vaccine side effects.

None of the interventions increased parents’ intent to vaccinate.

Then, a couple of weeks ago, a friend sent me a link to this piece describing research which seems to contradict that finding. The authors (Horne, et al.) concluded that

…highlighting factual information about the dangers of communicable diseases can positively impact people’s attitudes to vaccination.

These two conclusions seem to contradict each other. Which should we believe?

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Barbara Drescher taught quantitative and cognitive psychology, primarily at California State University, Northridge for a decade. Barbara was a National Science Foundation Fellow and a Phi Kappa Phi Scholar. Her research has been recognized with several awards and the findings discussed in Psychology Today. More recently, Barbara developed educational materials for the James Randi Educational Foundation. Read Barbara’s full bio or her other posts on this blog.

So stoned he doesn’t realize his quill is nowhere near the paper.

There is brand new evidence that Shakespeare was a pothead! This exciting story has appeared on the websites of TIME, the Los Angeles Times, CNBC, the Today Show, CNN, and many more outlets. And the brand new evidence is only fourteen years old! And it’s really weak evidence.

Francis Thackeray, Phillip Tobias Chair in Paleoanthropology at the Evolutionary Studies Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, recently published a short piece called “Shakespeare, plants, and chemical analysis of early 17th century clay ‘tobacco’ pipes from Europe” in the South African Journal of Science. But this isn’t the first time Thackeray has written about the topic. Oh, far from it. His one-page piece in the “Scientific Correspondence” section includes twelve end notes, nine of which cite nine different writings authored or co-authored by Thackeray.

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Eve Siebert contributes to the Skepticality podcast and is a panelist on the Virtual Skeptics webcast. She taught college writing and literature for many years. She has a Ph.D. in English literature from Saint Louis University. Her primary area of study is Old and Middle English literature, with secondary concentrations in Old Norse and Shakespeare. Read Eve’s full bio or her other posts on this blog.

Last month I was doing geologic field work in northern California, and I had the opportunity to travel across the Klamath Mountains. Naturally, I saw many of the signs of Bigfoot Country. There’s a tacky “museum” and store down in Garberville near the Humboldt Redwoods, right off Highway 101, and there are Bigfoot merchandisers everywhere in the Klamaths. But the epicenter of Squatcher country (as the hunters of Sasquatch call themselves) is the Willow Creek-Bluff Creek area, in the central Klamaths.

Willow Creek is a tiny little town deep in the forests of the Klamath Mountains, with a population of only 1743. Logging has been its main source of income in the past but today it is tourism. And Willow Creek is truly Bigfoot Central. Almost every business in town caters to Bigfoot tourism. There is a Bigfoot Motel, Bigfoot Books, Bigfoot Contracting Supply, Bigfoot Rafting Company, and Bigfoot Restaurant, just to mention a few with “Bigfoot” in their business name. Every Labor Day weekend (this year on Sept. 5, 2015), Willow Creek hosts its annual “Bigfoot Daze” festival. Most famous of all is the Willow Creek-China Flat Museum, with a room dedicated to its collections about Bigfoot. The exhibits are not that impressive: mostly hand-typed signs and labels, lots of fading newspaper clippings and fuzzy photographs, various casts of “Bigfoot prints,” and so on. The town also boasts numerous sculptures of Bigfoot in many places, including a more than twice-life-size statue outside the Bigfoot Museum, and redwood carvings outside the local Patriot gas station and the Visitor Information Center. There’s a Bigfoot Avenue and Little Foot Court, as well as a Patterson Avenue (and this town only has a few streets). Just like the areas around Loch Ness, and Lake Champlain (home of “Champ”), and other places in the cryptozoology lore, cryptid-tourism is big business, and supports a significant portion of the economy in a town as remote and tiny as Willow Creek.

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Dr. Donald Prothero taught college geology and paleontology for 35 years, at Caltech, Columbia, and Occidental, Knox, Vassar, Glendale, Mt. San Antonio, and Pierce Colleges. He earned his B.A. in geology and biology (highest honors, Phi Beta Kappa, College Award) from University of California Riverside in 1976, and his M.A. (1978), M.Phil. (1979), and Ph.D. (1982) in geological sciences from Columbia University. He is the author of over 35 books. Read Donald’s full bio or his other posts on this blog.

This post continues Blake’s exploration of the “Goddard’s Squadron Ghost” photo.

Read his first post on the topic, “Should Goddard’s Squadron Drop Dead Fred?” (published February 2, 2015).

Squadron photo allegedly showing the ghost of Freddy Jackson.

I’m no scientist. I sometimes wish I were, but at the end of the day I’m merely an enthusiast who tries to use scientific methodology in my daily life whenever it is appropriate to do so. One aspect of science which I am keenly aware of is that it is self-correcting. When evidence appears which is contrary to the hypothesis one is testing, science demands that the new evidence be accounted for and that if the evidence is sound, the hypothesis must be amended or discarded.

A few months ago I shared my research on the Freddie Jackson “ghost” photo (aka Goddard’s Squadron Ghost). I have been looking into the history of this photo for some time, and with the databases I was using to search for the existence of Freddie Jackson, I did not find evidence that such a person existed. But, to my delight, a reader of that article reached out to me and he had found the very proof I had been looking for. So, to answer my own question on the matter, should we drop dead Fred? Apparently, the answer is “no.” There really was a Freddie Jackson in the RAF whose personal details parallel elements of the Goddard/Capel story.

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Blake Smith is the producer and host of MonsterTalk, an official podcast of Skeptic magazine. He’s had a lifelong interest in science and the paranormal and enjoys researching the strange and unusual. By day he’s a computer consultant and by night he hunts monsters. He is married and has children. Puns are intentional; don’t bother alerting the management. Read Blake’s other posts on this blog.

Order the book from shop.skeptic.com

A few weeks ago, the internet was abuzz with claims that scientists were predicting a “new Ice Age” around 2030. Many media outlets ran misleading pictures of people walking through frozen wastelands, and other wintry scenes. Naturally, the climate deniers immediately jumped on this as proof that global warming wasn’t going to happen, or that scientists can’t get their stories straight. My email and Facebook were flooded with questions from people asking me whether it was true, and what did it all mean?

This story is a classic case of bad journalism run amok. The original source was just a re-published press release of a talk not yet given by one solar scientist, Dr. Valentina Zharkova. She works on solar magnetism, but has absolutely no training in atmospheres or climate science. It is just an initial report of a new mathematical model for the magnetic field behavior of the sun. It is not a peer-reviewed study, nor is it even published yet, so it hasn’t had the slightest scientific scrutiny. Contrary to all the breathless reporting, it shows no actual data for how much solar radiation will be emerging in 2030—just that the magnetic activity of the sun would be different. Magnetic activity of the sun does not translate into a simple prediction of how much radiation reaches the earth. And nowhere in this unreviewed press release does the scientist make the actual claim that there will be a new ice age in 2030. That was entirely made up by the media which completely misinterpreted and misreported the minimal information in the study.

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Dr. Donald Prothero taught college geology and paleontology for 35 years, at Caltech, Columbia, and Occidental, Knox, Vassar, Glendale, Mt. San Antonio, and Pierce Colleges. He earned his B.A. in geology and biology (highest honors, Phi Beta Kappa, College Award) from University of California Riverside in 1976, and his M.A. (1978), M.Phil. (1979), and Ph.D. (1982) in geological sciences from Columbia University. He is the author of over 35 books. Read Donald’s full bio or his other posts on this blog.

In this blog and in my book Reality Check, I’ve frequently complained about science-denying politicians pushing policies which are in direct conflict with scientific evidence and reality: the creationist agenda in public schools, distorting history to serve the religious extremists, or acting on behalf of their energy industry donors to deny the reality of climate change and attack the EPA, NASA, NOAA, the NSF, and legitimate scientific organizations. So it gives me great pleasure to praise public figures who stand up for science and science-based policy, and pass laws that benefit people and the environment, rather than powerful special interests and the science deniers of every stripe. Nowhere is this more apparent than my home state, California.

Immunizing Children

Last week, the state legislature passed, and Governor Jerry Brown signed into law a no-nonsense measure that made childhood vaccinations mandatory except for extraordinary medical circumstances. No more will the anti-vaxxers in my state be able to use their “personal beliefs” to endanger other children through their own foolishness and believing debunked garbage from the internet. The problem was a severe one in our state, with its huge population and large number of anti-vaxxers driven by Hollywood celebrities like Jenny McCarthy and Jim Carrey. The medical community has been battling the anti-vaxxers for years with limited success, until serious outbreaks of measles at Disneyland, and other deadly outbreaks of rubella and whooping cough started killing people. But State Senator Richard Pan, M.D., who sponsored the bill, managed to get it through both houses of the Legislature by big majorities (despite a handful of GOP naysayers who thought in impinged on “personal freedom and privacy”). Then Gov. Brown signed it as soon as it reached his desk, and the bill is now law.

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Dr. Donald Prothero taught college geology and paleontology for 35 years, at Caltech, Columbia, and Occidental, Knox, Vassar, Glendale, Mt. San Antonio, and Pierce Colleges. He earned his B.A. in geology and biology (highest honors, Phi Beta Kappa, College Award) from University of California Riverside in 1976, and his M.A. (1978), M.Phil. (1979), and Ph.D. (1982) in geological sciences from Columbia University. He is the author of over 35 books. Read Donald’s full bio or his other posts on this blog.

This post is the third and final in a series I began more than a year ago. The first post discussed how rationality differs from intelligence, how both may be measured, and what may keep intelligent people from behaving rationally. The second describes three of the four broad categories of factors involved in rational thinking while taking a closer look at how one thinking disposition, the need for cognition, affects decision-making and problem solving. I highly recommend reading the first two posts before continuing with this one as the background is important.

In summary, we tend to the think that people are irrational because they lack intelligence or knowledge. Both may contribute to rationality. However, intelligence and education are no guarantees of rationality because other factors such as cognitive laziness and open/closed-mindedness are just as, if not more, important. In other words, human beings tend to be irrational out of stupidity or ignorance, but also out of laziness or arrogance.

The scientific process addresses each of these factors to ensure that the answers we find are as accurate as possible. Although the scientific method itself is inherently intelligent, a good researcher must have a minimum level of intelligence in order to succeed as good research rises above bad through the process of peer review. Scientists conduct very thorough reviews of literature to produce theoretically sound hypotheses (addressing ignorance). Regarding cognitive laziness, science itself is curious; scientists would not be in the business if they were not intellectually curious and willing to do the work to find accurate answers. Finally, science is competitive and interactive, discouraging arrogance. An individual scientist may be overconfident, but the process of peer review and replication beats that arrogance down in order to produce a consensus view.

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Barbara Drescher taught quantitative and cognitive psychology, primarily at California State University, Northridge for a decade. Barbara was a National Science Foundation Fellow and a Phi Kappa Phi Scholar. Her research has been recognized with several awards and the findings discussed in Psychology Today. More recently, Barbara developed educational materials for the James Randi Educational Foundation. Read Barbara’s full bio or her other posts on this blog.

This post concludes a three-part series exploring the history of vitalism.

Read Part 1 and

Part 2.

Image by Daniel Loxton and Jim W. W. Smith.

Vitalism died a death of a thousand cuts. There was no single experiment, no one find that falsified the idea. Rather it was a shadow that shrank as the light of discovery grew.

One such event has become legendary in most modern science classrooms. In the late 18th century Italian physician Luigi Galvani was said to have brushed the sciatic nerve a frog he was dissecting with his metal instruments in such a way to cause the legs to twitch. This observation, it’s said, led to his research into connections between the emerging field of electrochemistry and physiology.

Galvani’s ‘electrical fluid’ theory paved the way for understanding how nervous impulses stimulate muscle movement, removing the need for some vague impetus or desire for movement.

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Mike McRae is an Australian science writer and teacher. He has worked for the CSIRO’s education group and developed resources for the Australian government, promoting critical thinking and science education through educational publications. His 2011 book Tribal Science: Brains, Beliefs and Bad Ideas explored humanity’s development to think scientifically—and pseudoscientifically—about the universe. Read Mike’s other posts on this blog.

This post continues a three-part series exploring the history of vitalism. Read Part 1 and continue on to Part 3.

A depiction of Paracelsus. This image was copied from a lost original which may have been painted from life. (Via Wikimedia Commons.)

The 16th century Swiss-German physician and alchemist Theopharastus von Honhenheim—better known as Paracelsus—saw little distinction between his studies in chemistry and medical biology. Famous for his quote on all things being poisons, Paracelsus believed chemistry lay at the heart of health and disease. Given the relationship between contemporary medicines and toxicology, with many treatments based on substances such as alcohol, arsenic, antimony, lead and mercury, it’s surprising his position wasn’t more widely held.

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Mike McRae is an Australian science writer and teacher. He has worked for the CSIRO’s education group and developed resources for the Australian government, promoting critical thinking and science education through educational publications. His 2011 book Tribal Science: Brains, Beliefs and Bad Ideas explored humanity’s development to think scientifically—and pseudoscientifically—about the universe. Read Mike’s other posts on this blog.

One of biology’s longest standing mysteries was explaining how complex life emerged from simpler chemical structures.

When the 19th century German embryologist Wilhelm Roux looked down the microscope at a frog’s egg, he saw a machine. A tiny, perfect molecular machine with chemical cogs and atomic gears. Life was analogically—indeed, almost literally—based on complex organic machinery. “Lehre von den Ursachen der organischen Gestaltungen,” he wrote[1]. Developmental mechanics is the cause of the organic form.

But Wilhelm had a rather big problem to solve. Cells reproduce by splitting in half before growing. Divide a machine and all you get is two simpler machines, each with half of their original pieces. How does something grow in complexity as its components seem to grow in simplicity?

The answer wouldn’t come for half a century. In the meantime, an old fashioned belief in ghostly forces would have one last opportunity to prove itself worthy of being considered scientific.

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Mike McRae is an Australian science writer and teacher. He has worked for the CSIRO’s education group and developed resources for the Australian government, promoting critical thinking and science education through educational publications. His 2011 book Tribal Science: Brains, Beliefs and Bad Ideas explored humanity’s development to think scientifically—and pseudoscientifically—about the universe. Read Mike’s other posts on this blog.

Anna Maltese (left) presents Daniel Loxton with a bizarre coincidence after his talk at The Amazing Meeting 2014, while his wife Cheryl Hebert looks on. (Photograph by David Patton. Used with permission.)

There are few experiences so striking—so deeply imbued with apparent meaning—as a remarkable coincidence. But when is a coincidence genuinely meaningful rather than merely unexpected? And when is it neither, but instead (as skeptical psychologist Joseph Jastrow described such happenstances in 1900) “just what the normal distribution of such phenomena would lead us to expect”?1 People often find it difficult to view such subjectively jarring experiences from a statistical perspective, even when analysis of the odds is in fact possible. (Sometimes it isn’t.) As Jastrow observed,

It would be pleasant to believe that the application of the doctrine of chances to problems of this character is quite generally recognized; but this recognition is so often accompanied by the feeling that the law very clearly applies to all cases but the one that happens to be under discussion, that I fear the belief is unwarranted.2

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Daniel Loxton is the Editor of INSIGHT at Skeptic.com and of Junior Skeptic, the 10-page kids’ science section bound within Skeptic magazine. Daniel has been an avid follower of the paranormal literature since childhood, and of the skeptical literature since his youth. He is also an award-winning author. Read Daniel’s full bio or his other posts on this blog.

Jason Loxton during a 2010 research trip to study graptolites in China.

What is “biostratigraphy,” and what on Earth does it have to do with sharks…or with pancakes?

Listen to biostratigrapher Jason Loxton (my brother, and a Junior Skeptic contributor) answer these questions in a quick and breezy CBC radio interview (alternate link). Broadcast on Monday June 22, the interview summarizes Jason’s talk for the “Children’s University” public outreach event, titled “Sharks, Fossils and Meteors: How Geologists Gave the Earth a Birthday.” This free-to-the-public lecture for kids took place yesterday (June 23).

A lab instructor at Cape Breton University and Ph.D. candidate at Dalhousie University, Jason studies the taxonomy and distribution of Ordovician/Silurian graptolites—or “really boring-looking smudges,” he says, cheerfully. This eye-straining endeavor may be “unglamorous and decidedly not ‘trendy,'” as he describes it, but it is just the type of ongoing fossil detective work which has allowed generations of geologists to painstakingly piece together the history of our planet. This project, biostratigraphy, “uses fossils to divide the rock record into relative units of time.” And for that, modest fossils like Jason’s smudges are just the thing.

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Daniel Loxton is the Editor of INSIGHT at Skeptic.com and of Junior Skeptic, the 10-page kids’ science section bound within Skeptic magazine. Daniel has been an avid follower of the paranormal literature since childhood, and of the skeptical literature since his youth. He is also an award-winning author. Read Daniel’s full bio or his other posts on this blog.

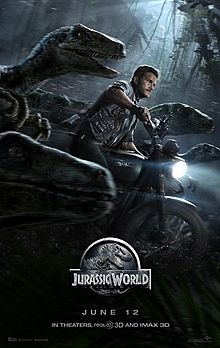

Ever since Jurassic World (watch trailer) came out two weeks ago (and is now the fastest movie ever to make a billion dollars), people have been asking me again and again what I thought of the movie as a vertebrate paleontologist, and someone who has written often about dinosaurs, and even done some research on them. My usual short answer is: “A big disappointment: it’s an OK monster movie, lousy science. And it could have been SO much better.” This has been the consensus opinion among nearly all the scientists and science bloggers (especially dinosaur paleontologists) who have commented on it, including John Long, Jim Kirkland and Thomas Holtz, Brian Switek, Kyle Hill, John Conway, Mark Loewen, Darren Naish, and many others.

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Dr. Donald Prothero taught college geology and paleontology for 35 years, at Caltech, Columbia, and Occidental, Knox, Vassar, Glendale, Mt. San Antonio, and Pierce Colleges. He earned his B.A. in geology and biology (highest honors, Phi Beta Kappa, College Award) from University of California Riverside in 1976, and his M.A. (1978), M.Phil. (1979), and Ph.D. (1982) in geological sciences from Columbia University. He is the author of over 35 books. Read Donald’s full bio or his other posts on this blog.

A detail from the cover of the second edition of Nostrums and Quackery (1912), from the American Medical Association. Browse the first edition online at Archive.org.

“The American Medical Association is finally taking a stand on quacks like Dr. Oz,” announced a post yesterday by Julia Belluz. A health writer at Vox, Belluz has emerged as a sharp critic of popular medical talk show personality Dr. Mehmet Oz with posts such as this, this, and this. (I recommend her thoughtful reflection on the ethics, challenges, and public health concerns of countering medical misinformers, titled “How should journalists cover quacks like Dr. Oz or the Food Babe?” Generations of skeptical critics of quackery have asked those same troubling questions.)

Belluz cites an activist medical student named Benjamin Mazer, who reports on the outcome of a policy proposal recently brought before the American Medical Association’s (AMA) House of Delegates:

The delegates, who represent doctors throughout the country, voted to support the policy proposal as we wrote it. The AMA will now be taking the lead in crafting ethical and professional guidelines for physicians who wish to disseminate medical information in the media. The AMA will also write a report describing how physicians may be subject to discipline for violating medical ethics in the media. And finally, the AMA will be releasing a public statement reiterating our professional values and condemning doctors who use the media unethically. … Many of the leading experts in medical ethics are a part of the AMA. They will now go to work clarifying the nuances of “mass medicine” and will provide recommendations. No longer will quacks be able to benefit from a lack of specific standards and professional codes.

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Daniel Loxton is the Editor of INSIGHT at Skeptic.com and of Junior Skeptic, the 10-page kids’ science section bound within Skeptic magazine. Daniel has been an avid follower of the paranormal literature since childhood, and of the skeptical literature since his youth. He is also an award-winning author. Read Daniel’s full bio or his other posts on this blog.

“The Vision of Columbus” after de Bry, as it appeared in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine No. 389, October 1882. (Daniel Loxton’s collection.)

Mermaids—the topic of my Junior Skeptic 48 story bound inside Skeptic Vol. 18, No. 3—are usually considered fantastical, purely imaginary creatures. (Or, at least, they were until Animal Planet and the Discovery Channel aired their infamous 2012 and 2013 documentary-style hoaxes Mermaids: The Body Found and Mermaids: The New Evidence. These hoaxes are discussed in detail in the same issue of Junior Skeptic, in a section excerpted here at INSIGHT.)

In a culture that accepts all manner of supernatural wonders, potions, and wizardry, mermaids have enjoyed a special place in the rhetoric of both organized and folk skepticism. Along with unicorns and leprechauns, mermaids have frequently served as a go-to example of a self-evidently silly claim. When science reporter John Noble Wilford1 accompanied a monster-hunting group to Loch Ness in 1976 for a series of New York Times articles, for example, skeptic Philip J. Klass2 used mermaids to poke fun at the whole enterprise. Klass wrote to the paper in his (pretend) role as “Director Pro-Tem” of the (non-existent) “Mermaid Investigation Sightings Society”:

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Daniel Loxton is the Editor of INSIGHT at Skeptic.com and of Junior Skeptic, the 10-page kids’ science section bound within Skeptic magazine. Daniel has been an avid follower of the paranormal literature since childhood, and of the skeptical literature since his youth. He is also an award-winning author. Read Daniel’s full bio or his other posts on this blog.

This look back at Discovery’s 2012 and 2013 mermaids hoaxes is an excerpt from Junior Skeptic 48 (published in 2013 inside Skeptic magazine Vol. 18, No. 3). The damage done to English-language television’s premier nonfiction brand by these and subsequent misleading ratings stunts (including what I described as “the profound awfulness” of 2014’s Russian Yeti: The Killer Lives) has been widely discussed by critics. As I reflected last year, “At this point, Discovery could announce that they’d made a sandwich during Monster Week and I’d wonder if that were true.”

As the network attempts to regain its dignity, this seemed an opportune moment to review how they put themselves in this compromised position.

Junior Skeptic is written for (older) children and does not include endnotes, though I often call out important sources in sidebars or the text of the story itself. However, I’ve included some links and relevant citations here for your interest.

Monster hunters have remained interested in mermaid-like creatures such as the Ri [a cryptozoological mystery from Papua New Guinea—see Junior Skeptic 48], and mermaid sightings are still sometimes reported in countries in Africa and elsewhere around the world. But people in the United States and other industrialized countries generally think of mermaids as completely imaginary fantasy creatures like dragons, gremlins, or leprechauns.

Or at least, they did. Then, in 2012, the Animal Planet television channel aired a documentary-style program called Mermaids: The Body Found. [Watch trailer.] Three and a half million viewers watched in astonishment as people identified as U.S. government scientists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) looked straight into the camera and told the public about incredible evidence for the existence of mermaids. Not only are mermaids real, claimed the program, but they are an evolutionary offshoot of the human family tree!

CONTINUE READING THIS POST…

Daniel Loxton is the Editor of INSIGHT at Skeptic.com and of Junior Skeptic, the 10-page kids’ science section bound within Skeptic magazine. Daniel has been an avid follower of the paranormal literature since childhood, and of the skeptical literature since his youth. He is also an award-winning author. Read Daniel’s full bio or his other posts on this blog.

← PREVIOUS

NEXT →