On the 75th anniversary of nuclear weapons, Dr. Michael Shermer presents a moral case for their use in ending WWII and the deterrence of Great Power wars since, and a call to eventually eliminate them. This essay was excerpted, in part, from Michael Shermer‘s book, The Moral Arc, in the chapter on war.

Read the essay below, or listen to it being read by the author, Michael Shermer:

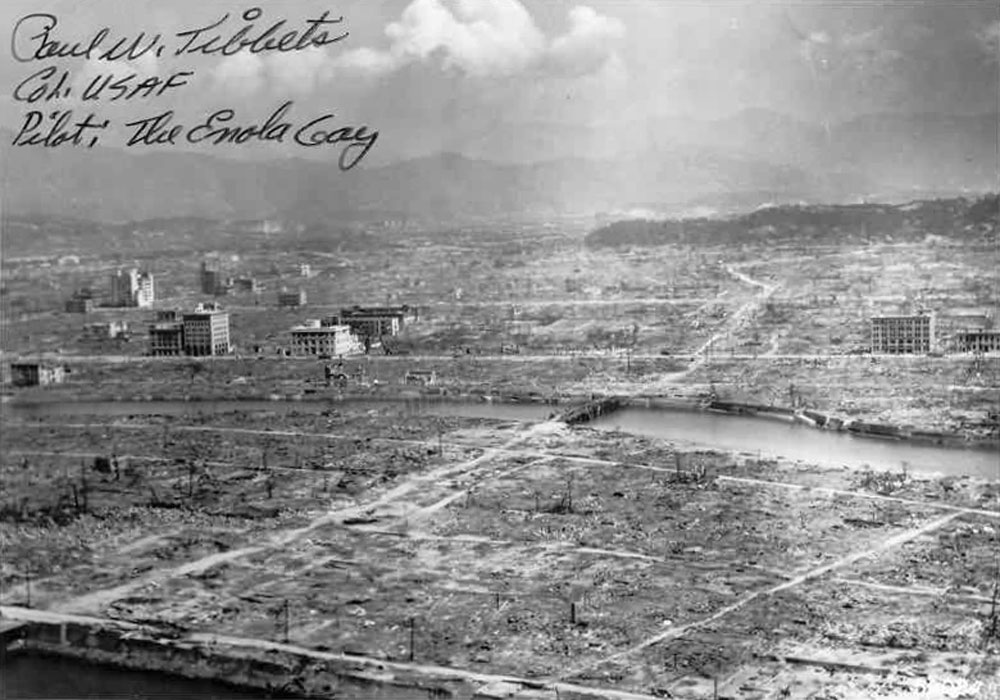

On August 6, 1945 the Little Boy gun-type uranium-235 bomb exploded with an energy equivalent of 16–18 kilotons of TNT, flattening 69 percent of Hiroshima’s buildings and killing an estimated 80,000 people and injuring another 70,000.

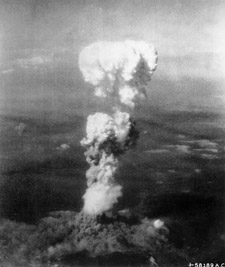

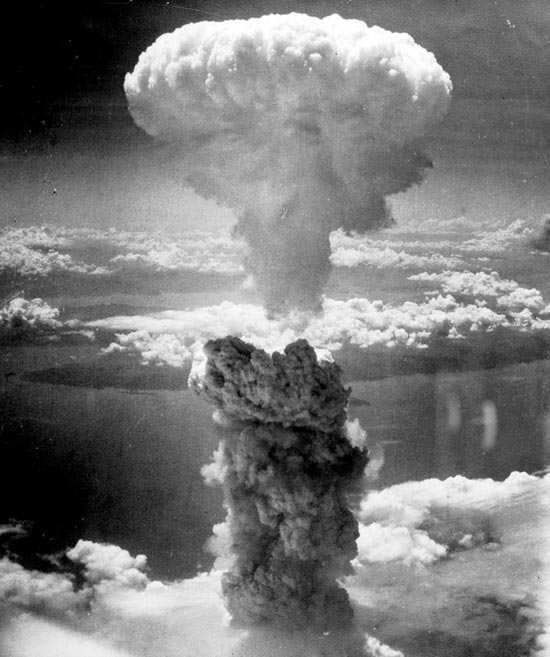

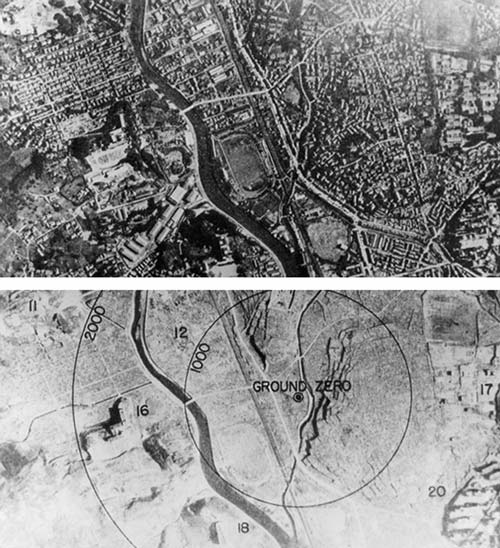

Three quarters of a century ago this summer, nuclear weapons altered our civilization forever. On July 16 the Trinity plutonium bomb detonated with the energy equivalent of 22 kilotons (22,000 metric tons) of TNT, sending a mushroom cloud 39,000 feet into the atmosphere. The explosion left a crater 76 meters wide filled with radioactive glass called trinitite (melted quartz grained sand). It could be heard as far away as El Paso, Texas. On August 6 the Little Boy gun-type uranium-235 bomb exploded with an energy equivalent of 16–18 kilotons of TNT, flattening 69 percent of Hiroshima’s buildings and killing an estimated 80,000 people and injuring another 70,000. On August 9 the Fat Man plutonium implosion-type bomb with the energy equivalence of 19-23 kilotons of TNT leveled around 44 percent of Nagasaki, killing an estimated 35,000 to 40,000 people and severely wounding another 60,000.1

The aftermath of Little Boy

On August 9, 1945 the Fat Man plutonium implosion-type bomb with the energy equivalence of 19–23 kilotons of TNT leveled around 44 percent of Nagasaki, killing an estimated 35,000 to 40,000 people and severely wounding another 60,000.

Before and aftermath of Nagasaki

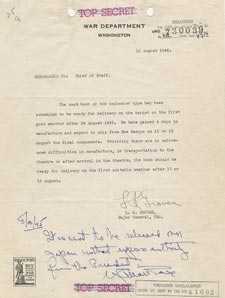

Click image to view larger PDF. Had the Japanese military hardliners had their way to continue the war into the fall, Groves had three more bombs readied for September and another three for October. Here he instructs his Chief of Staff that the next bomb will be ready to drop on after August 24. Emperor Hirohito capitulated on August 15, thereby saving millions of lives of his citizens.

As documented in the memo below dated August 10, 1945, if the Japanese had not surrendered the head of the Manhattan Project, Major General Leslie R. Groves, had another Fat Man-type plutonium implosion bomb ready to go after August 24 that would have likely killed another 50,000 to 100,000 people.2 And had the Japanese military hardliners had their way to continue the war into the fall, Groves had three more bombs readied for September and another three for October. President Harry Truman was not exaggerating when he threatened Japan with “a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this Earth.” Truman did agonize about dropping more nukes on Japan, troubled as he was by the thought of more innocents and noncombatants being killed. He wrestled that decision away from the military. (Note Groves’ handwritten addendum to his memo that “It is not to be released on Japan without express authority from the President.” U.S. presidents have had sole authority to use nuclear weapons ever since.) However, further bombings proved unnecessary. On August 15 Emperor Hirohito, against the wishes of some of Japan’s military leaders, announced on the radio that Japan would capitulate. On September 2 they signed the surrender documents in Tokyo Bay, ending the Second World War.3

On this 75th anniversary of the summer of the bomb I want to make the case that their use was necessary to end the war, that their continued existence has acted as a deterrence against another Great Power war — but that we must eliminate them entirely for the long-term existence of our civilization and possibly our species.

Since 1945 a cadre of critics have proffered the claim that atomic bombs were unnecessary to bring about the end of World War II (or, at least, the Fat Man Nagasaki bomb was superfluous), and thus this act was immoral, illegal, or even a crime against humanity. Robert Oppenheimer and other physicists like Leo Szilard who worked on the Manhattan Project expressed reservations. “The physicists have known sin,” Oppenheimer opined. He went to Truman and confessed “Mr. President. I feel I have blood on my hands,” to which the President recalled “I told him the blood was on my hands — to let me worry about that.” Truman promptly dismissed Oppenheimer and told Secretary of State Dean Acheson, “I don’t want to see that son-of-a-bitch in this office ever again.”4

In 1946 the Federal Council of Churches issued a statement declaring, “As American Christians, we are deeply penitent for the irresponsible use already made of the atomic bomb. We are agreed that, whatever be one’s judgment of the war in principle, the surprise bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are morally indefensible.”5 In 1967 the linguist and contrarian politico Noam Chomsky called the two bombings “the most unspeakable crimes in history.”6

More recently, in his history of genocide titled Worse Than War, the historian Daniel Goldhagen opens his analysis by calling the U.S. President Harry Truman “a mass murderer” because in ordering the use of atomic weapons he “chose to snuff out the lives of approximately 300,000 men, women and children.” Goldhagen opines that “it is hard to understand how any rightthinking person could fail to call slaughtering unthreatening Japanese mass murder.”7 Goldhagen defines “genocide” broadly enough to equate it with “mass murder” (without ever defining what, exactly, that means). In morally equating Harry Truman with Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Pol Pot, Goldhagen allows himself to be constrained by the categorical thinking that prevents one from discerning the different kinds, levels, and motives for large scale military violence. By this reasoning, nearly every act that kills a large number of people could be considered genocidal because there are only two categories — mass murder and non-mass murder.

By contrast, continuous thinking allows us to distinguish the differences between types of mass killings (some scholars define genocide as one-sided killing by armed people of unarmed people), their context (during a state war, civil war, ethnic cleansing), motivations (termination of hostilities or extermination of a people), and quantities (hundreds to millions) along a sliding scale. In 1946 the Polish jurist Raphael Lemkin created the term genocide and defined it as “a conspiracy to exterminate national, religious or racial groups.”8 That same year the U.N. General Assembly defined genocide as “a denial of the right of existence of entire human groups.”9 More recently, in 1994 the highly respected philosopher Steven Katz defined genocide as “the actualization of the intent, however successfully carried out, to murder in its totality any national, ethnic, racial, religious, political, social, gender or economic group.”10

By these definitions, the dropping of Fat Man and Little Boy were not acts of genocide. The difference between Truman and the others is in the context and motivation of the act. In their genocidal actions against targeted people, Hitler, Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot had as their objective the total elimination of a group. The killing would only stop when every last pursued person was exterminated (or if the perpetrators were stopped or defeated). Truman’s goal in dropping the bombs was to end the war with Japan (which it did), not to eliminate the Japanese people (which it didn’t). That the U.S. provided considerable financial, personnel, and material support to help rebuild Japan into a world economic power puts the lie to the eliminationist accusation.11

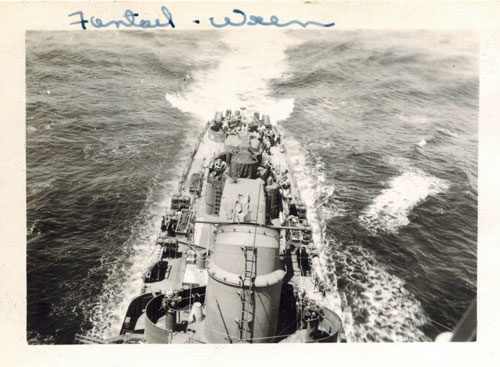

The author’s father, Richard Shermer, in 1945, serving aboard the USS Wren.

More broadly morally, if we ground morality in the survival and flourishing of sentient beings,12 by that measure, then not only did Fat Man and Little Boy end the war and stop the killing, they saved lives — very probably millions of lives, both Japanese and American. My father Richard Shermer was possibly one such survivor. During the Second World War he served aboard the USS Wren (DD-568), a Fletcher-class destroyer assigned to protect aircraft carriers and other large capital ships from Japanese submarines and from Kamikaze planes on what was called antiaircraft radar picket watch. His ship was so attacked several times but sustained no major damage. The Wren was part of the larger fleet that was working its way toward Japan, escorting the carriers whose planes were bombarding the Japanese homeland in preparation for the planned invasion. My father told me that everyone onboard dreaded that day because they had heard of the horrific carnage resulting from the invasion of just two tiny islands held by the Japanese — Iwo Jima and Okinawa. If that was any indication of what was to come with a full-scale invasion, the contemplation of it was almost too much to bear.13

The USS Wren, a Navy destroyer deployed to protect aircraft carriers from suicidal Kamikaze pilots while their planes bombarded the Japanese homeland in preparation for the invasion that never came, thanks to Fat Man and Little Boy.

Click an image above to enlarge it. Four photos taken by Richard Shermer on board the USS Wren, pictured fore and aft, accompanying the aircraft carrier USS Lexington, and arriving in Tokyo Bay in late August, 1945 in preparation for the surrender ceremony on September 2, marking the end of the Second World War.

During the invasion of Iwo Jima there were approximately 26,000 American casualties that included 6,821 dead in the 36-day battle. How fiercely did the Japanese defend that little volcanic rock 700 miles from Japan? Of the 22,060 Japanese soldiers assigned to fight to the bitter end, only 216 survived.14 The subsequent battle for Okinawa, only 340 miles from the Japanese mainland, was fought even more ferociously, resulting in a staggering body count of 240,931 dead, including 77,166 Japanese soldiers, 14,009 American soldiers, plus an additional 149,193 Japanese civilians living on the island who either died fighting or committed suicide rather than let themselves be captured.15 With an estimated 2.3 million Japanese soldiers and 28 million Japanese civilian militia prepared to defend their island nation to the death,16 it was clear to all what an invasion of the Japanese mainland would entail.

It is from these cold hard facts that Truman’s advisors estimated that between 250,000 and one million American lives would be lost in an invasion of Japan.17 General Douglas MacArthur estimated that there could be a 22:1 ratio of Japanese to American deaths, which translates to a minimum death toll of 5.5 million Japanese.18 By comparison, cold though it may sound, the body count from both atomic bombs — about 200,000–300,000 total (Hiroshima: 90,000–166,000 deaths, Nagasaki: 60,000–80,000 deaths19) — was a bargain.

In any case, if Truman hadn’t ordered the bombs dropped, General Curtis LeMay and his fleet of B-29 bombers would have continued pummeling Tokyo and other Japanese cities into rubble. When asked to predict when the war would end based on his bombing program, LeMay said September 1, because that was when there would be nothing left of Japan to bomb. The death toll from conventional bombing would have been just as high as that produced by the two atomic bombs, if not higher. Previous mass bombing raids had produced Hiroshima-level death rates, and it is likely that more than just two cities would have been destroyed before the Japanese surrendered. Compare, for example, Little Boy’s energy equivalent of 16,000–19,000 tons of TNT to the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey estimate that this was the equivalent of 220 B-29s carrying 1,200 tons of incendiary bombs, 400 tons of high-explosive bombs, and 500 tons of anti-personnel fragmentation bombs, with an equivalent number of casualties.20 In fact, on the night of March 9–10, 1945, 279 B-29s dropped 1,665 tons of bombs on Tokyo, leveling 15.8 square miles of the city, killing 88,000 people, injuring another 41,000, and leaving another million homeless.21

On the night of March 9–10, 1945, 279 B-29s dropped 1,665 tons of bombs on Tokyo, leveling 15.8 square miles of the city, killing 88,000 people, injuring another 41,000, and leaving another million homeless. This is the result.

These facts also help refute the claim that the alternative scenario of dropping an atomic bomb on an uninhabited island or bay to demonstrate its destructive force would have worked to convince the Japanese to surrender. Given that they refused to capitulate even after numerous cities were obliterated by conventional bombs and Hiroshima was erased from the map by an atomic bomb it seems unlikely this more benign strategy would have worked.22

On balance, then, dropping the atomic bombs was the least destructive of the options on the table. Although we wouldn’t want to call it a moral act, it was in the context of the time the least immoral act by the criteria of lives saved. That said, we should also recognize that the several hundred thousand killed is still a colossal loss of life. The fact that the invisible killer of radiation continued its effects long after the bombings should dissuade us from ever using such weapons again. Along that sliding scale of evil, in the context of one of the worst wars in human history that included the singularly destructive Holocaust of six million murdered, it was not, pace Chomsky, the most unspeakable crime in history — not even close — but it was an event in the annals of humanity never to be forgotten and, hopefully, never to be repeated.

When I was an undergraduate at Pepperdine University in 1974, the father of the hydrogen bomb — Edward Teller — spoke at our campus in conjunction with the awarding of an honorary doctorate. His message was that deterrence works. At the time I remember thinking — like so many politicos were saying — “yeah, but a single slip-up is all it takes.” Popular films such as Fail Safe and Dr. Strangelove reinforced the point. But the blunder never came (and the close calls were kept secret for decades). In the game theoretic strategy of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD), deterrence works because neither side has anything to gain by initiating a first strike against the other. The retaliatory capability of both is such that a first strike would most likely lead to the utter annihilation of both countries (along with much of the rest of the world). “It’s not mad!” proclaimed Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara. “Mutual Assured Destruction is the foundation of deterrence. Nuclear weapons have no military utility whatsoever, excepting only to deter one’s opponent from their use. Which means you should never, never, never initiate their use against a nuclear-equipped opponent. If you do, it’s suicide.”23

The logic of deterrence was first articulated in 1946 by the American military strategist Bernard Brodie in his appropriately titled book The Absolute Weapon, in which he noted the break in history that atomic weapons brought with their development: “Thus far the chief purpose of our military establishment has been to win wars. From now on, its chief purpose must be to avert them. It can have almost no other purpose.”24 As Dr. Strangelove explained in Stanley Kubrick’s classic Cold War film: “Deterrence is the art of producing in the mind of the enemy the fear to attack.” Said enemy, of course, must know that you have at the ready such destructive devices, and that is why “The whole point of a doomsday machine is lost if you keep it a secret!”25

Dr. Strangelove was a black comedy that parodied MAD by showing what can happen when things go terribly wrong, in this case when General Jack D. Ripper becomes unhinged at the thought of “Communist infiltration, Communist indoctrination, Communist subversion, and the international Communist conspiracy to sap and impurify all of our precious bodily fluids” and orders a nuclear first strike against the Soviet Union. Given this unfortunate incident and knowing that the Russkis know about it and will therefore retaliate, General “Buck” Turgidson pleads with the president to go all out and launch a full first strike. “Mr. President, I’m not saying we wouldn’t get our hair mussed, but I do say no more than ten to twenty million killed, tops, uh, depending on the breaks.”26

This isn’t far off real projected casualties (Kubrick was a student of Cold War strategy), as in 1957 Strategic Air Command (SAC) estimated that between 360 and 525 million casualties would be inflicted in the first week of a nuclear exchange with the Soviet block.27 In 1968 Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara gave these figures for MAD to work: “In the case of the Soviet Union, I would judge that a capability on our part to destroy, say, one-fifth to one-fourth of their population and one-half of her industrial capacity would serve as an effective deterrent.” With a population of the time of about 128 million, this translates to 25–32 million dead.28 A 1979 report from the Office of Technology Assessment for the U.S. Congress, entitled The Effects of Nuclear War, estimated that 155 to 165 million Americans would die in an all-out Soviet first strike (unless people made use of existing shelters near their homes, reducing fatalities to 110–120 million). The population of the U.S. at the time was 225 million, so the estimated percent that would be killed ranged from 49 percent to 73 percent. Staggering.

Deterrence has worked so far — no nuclear weapon has been detonated in a conflict of any kind in 75 years — but it would be foolish to think of deterrence as a permanent solution.29 As long ago as 1795, in an essay titled Perpetual Peace, Immanuel Kant worked out what such deterrence ultimately leads to: “A war, therefore, which might cause the destruction of both parties at once … would permit the conclusion of a perpetual peace only upon the vast burial-ground of the human species.” (Kant’s book title came from an innkeeper’s30 sign featuring a cemetery — not the type of perpetual peace most of us strive for.) Deterrence acts as only a temporary solution to the Hobbesian temptation to strike first (also called the security dilemma in which a nation arming in defense triggers other nations to also arm in defense), allowing both Leviathans to go about their business in relative peace, settling for small proxy wars, which themselves have been in decline for decades.31

In the long run we need to work toward a world free of nuclear weapons. The risks of accidents or a deranged Dr. Strangelove-type character triggering a nuclear exchange is too high for a MAD deterrence strategy to be a permanent solution to the security dilemma it was invented to solve. Authors such as Richard Rhodes in his nuclear tetralogy (The Making of the Atomic Bomb, Dark Sun, Arsenals of Folly, and The Twilight of the Bombs32), and Eric Schlosser in Command and Control,33 leave readers with vertigo knowing how many close calls there have been. To name but a few: the jettisoning of a Mark IV atomic bomb in British Columbia in 1950; the crash of a B-52 carrying two Mark 39 nuclear bombs in North Carolina; the Cuban Missile Crisis; the Able Archer 83 Exercise in Western Europe that the Soviets misread as the buildup to a nuclear strike against them; the Titan II Missile explosion in Damascus, Arkansas that narrowly avoided eradicating the entire city off the map; and Stanislav Petrov’s decision not to trigger a retaliatory strike against the U.S. based on reports from the Soviet early warning satellite system of incoming ballistic missiles. It is not for nothing that Petrov is known as “the man who saved the world.”34

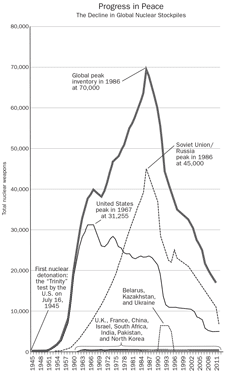

Thus, in the long run we must get to Nuclear Zero, but in the short run there are so many hurdles that few think we are anywhere near such a lofty goal. In two episodes of my Science Salon podcast Fred Kaplan, the national security journalist and author of several books on nuclear weapons, and William J. Perry, Secretary of Defense under President Clinton and a staunch advocate for eliminating nuclear weapons, both told me that they did not think this could happen any time soon, even while their books outline how it could be done.35 In The Moral Arc I summarized the consensus by experts on the most important steps to take to reduce the risk of nuclear weapons and to work toward a world free of them, including: (1) enact a “no first use” policy, (2) take all weapons off of “launch on warning”; (3) increase the warning and decision times for launching a retaliatory strike; (4) remove from the President the sole authority to launch nuclear weapons; (5) uphold non-proliferation agreements; (6) widen the taboo from using nuclear weapons to owning them; (7) increase economic interdependence; (8) expand democratic governance; (9) reduce spending on nuclear weapons; and (10) continue the disarmament of existing nuclear weapons. To that end, it is encouraging to see the decline in the total number of nuclear warheads to around 16,000 from the peak of around 70,000 in 1986, as visualized in the figure below.36

Click image to enlarge. The decline in the total number of nuclear warheads to around 16,000 from the peak of around 70,000 in 1986.

I should note that some security scholars, along with many political theorists and leaders, think that the path to peace is more deterrence through more and better nuclear weapons. President Trump, for example, insists on renovating our aged nuclear weapons systems to the tune of $1.2 trillion between 2017 and 2046, an upgrade program37 he inherited from President Obama. And despite winning the Nobel Peace Prize for working toward nuclear nonproliferation, Obama nevertheless backed off from initiating a “no first use” policy under pressure from our NATO allies, who were worried that Russian saber rattling and border expansion might be encouraged if an escalation from conventional to nuclear weapons was no longer on the defense table.38

Similarly, the late political scientist Kenneth Waltz thought that allowing Iran to go nuclear would bring stability to the Middle East because “in no other region of the world does a lone, unchecked nuclear state exist. It is Israel’s nuclear arsenal, not Iran’s desire for one, that has contributed most to the current crisis. Power, after all, begs to be balanced.”39 Except for when it doesn’t, as in the post-1991 period after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the unipolar dominance of the United States. No other medium-size power rose to fill the vacuum, no rising power started wars of conquest to consolidate more power, and the only other candidate, China, has remained war-free for almost four decades. Given Iran’s outlier status in the international system and their avowed promise to “wipe off the map” Israel, anyone who would join a Fair-Play-for-Nuclear-Iran-Committee has lost their moral compass.

This all just shows how difficult it is going to be to get to a world without nukes. Nevertheless, we have to try. One more statistic is sobering in this regard, as noted by the anti-nuclear scientist and activist David Barash: The U.S. has a triad of nuclear weapons: land (missiles), air (bombers) and sea (submarines). A single Trident sub carries 20 nuclear-tipped missiles, each one of which has eight independently targetable warheads of about 465 kilotons, or about 30 times the destructive power of Little Boy. So, one sub packs the equivalent of 4,800 Hiroshimas (20 x 8 x 30), and we have 18 Trident submarines, or the equivalent of 86,400 Hiroshimas!40 In the words of President Obama during a briefing about our nuclear capability: “Let’s stipulate that this is all insane.”41

The use of nuclear weapons for both ending wars and deterring them is a 20th century phenomenon that can be phased out for the new century. As the political scientist Christopher Fettweis notes in his book Dangerous Times?, despite the popularity of such intuitive notions as the “balance of power” — based on a small number of non-generalizable cases from the past that are in any case no longer applicable to the present — so-called “clashes of civilization” like the world wars of the 20th century are extremely unlikely to happen in the highly interdependent world of the 21st century. In fact, Fettweis shows, never in history has such a high percentage of the world’s population lived in peace. Conflicts of all forms have been steadily dropping since the early 1990s, and even terrorism can bring states together in international cooperation to combat a common enemy.42

The abolition of nuclear weapons is a complex and difficult puzzle that has been studied extensively by scholars and scientists for over half a century. The many problems and permutations of getting from here to there are legion, and there is no single sure-fire pathway to zero. Nevertheless, it is a soluble problem, and humans are nothing if not innovative problem solvers.43 I do not believe that the deterrence trap is one from which we can never extricate ourselves, and the remaining threats should direct us to work toward Nuclear Zero sooner rather than later. In the meantime, minimum is the best we can hope for given the complexities of international relations, but given enough time, as Shakespeare poetically observed…

Time’s glory is to calm contending kings,

To unmask falsehood and bring truth to light,

To stamp the seal of time in aged things,

To wake the morn and sentinel the night, …

To slay the tiger that doth live by slaughter, …

To cheer the ploughman with increased crops,

And waste huge stones with little water-drops.”44

About the Author

Dr. Michael Shermer is the Founding Publisher of Skeptic magazine, the host of the Science Salon Podcast, and a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University where he teaches Skepticism 101. For 18 years he was a monthly columnist for Scientific American. He is the author of New York Times bestsellers Why People Believe Weird Things and The Believing Brain, Why Darwin Matters, The Science of Good and Evil, The Moral Arc, and Heavens on Earth. His new book is Giving the Devil His Due: Reflections of a Scientific Humanist.

References

- Rhodes, Richard. 1986. The Making of the Atomic 1 Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II, A Collection of Primary Sources. National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 162. George Washington University. https://bit.ly/2WMuDNM See also: “The Third Shot.” https://bit.ly/39eCTuW

- DeNooyer, Rushmore. 2015. The Bomb. PBS documentary. https://to.pbs.org/3f2yyfw

- Bird, Kai and Martin J. Sherwin. 2007. American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. New York: Knopf, 332.

- Quoted in: Marty, Martin E. 1996. Modern American Religion, Vol 3: Under God, Indivisible, 1941–1960. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 117.

- Chomsky Noam. 1967. “The Responsibility of Intellectuals.” The New York Review of Books, 8(3).

- Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah. 2009. Worse Than War: Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity. New York: PublicAffairs, 1, 6.

- Lemkin, Raphael. 1946. “Genocide.” American Scholar, 15(2), 227–230.

- United Nations General Assembly Resolution 96(1): “The Crime of Genocide.”

- Katz, Steven T. 1994. The Holocaust in Historical Perspective, Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kugler, Tadeusz, Kyung Kook Kang, Jacek Kugler, Marina Arbetman-Rabinowitz, and John Thomas. 2013. “Demographic and Economic Consequences of Conflict.” International Studies Quarterly, March, 57(1), 1–12.

- Shermer, Michael. 2015. The Moral Arc: How Science and Reason Lead Humanity to Truth, Justice, and Freedom. New York: Henry Holt, 11.

- In 2002 I attended the reunion of the Wren crew in my father’s stead and confirmed his memories.

- Toland, John. 1970. The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936–1945. New York: Random House, 731.

- “The Cornerstone of Peace — Number of Names Inscribed.” Kyushu-Okinawa Summit 2000: Okinawa G8 Summit Host Preparation Council, 2000. See also: Pike, John. 2010. “Battle of Okinawa.” Globalsecurity.org; Manchester, William. 1987. “The Bloodiest Battle of All.” The New York Times, June 14.

- Giangreco, Dennis M. 2009. Hell to Pay: Operation Downfall and the Invasion of Japan 1945–1947. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 121–124.

- Giangreco, Dennis M. 1998. “Transcript of ‘Operation Downfall [U.S. Invasion of Japan]: US Plans and Japanese Counter-Measures. Beyond Bushido: Recent Work in Japanese Military History. https://bit.ly/2ZYCLwu See also: Maddox, Robert James. 1995. “The Biggest Decision: Why We Had to Drop the Atomic Bomb.” American Heritage, 46(3).

- Skates, John Ray. 2000. The Invasion of Japan: Alternative to the Bomb. University of South Carolina Press, 79.

- Putnam, Frank W. 1998. “The Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission in Retrospect.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, May 12, 95(10), 5426–5431.

- K’Olier, Franklin (Ed.) 1946. United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Sum 20 mary Report (Pacific War). Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office. https://bit.ly/32TsOSL

- Rhodes, 1984, op cit., 599.

- Ibid.

- Quoted in: Cold War: MAD 1960–1972. 1998. BBC Two Documentary. Transcript: https://bit.ly/2EimnyA. Film: https://bit.ly/2WVLsFX

- Brodie, Bernard. 1946. The Absolute Weapon: Atomic Power and World Order. New York: Harcourt Brace, 79.

- Kubrick, Stanley. 1964. Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. Columbia Pictures. http://youtu.be/2yfXgu37iyI

- Ibid.

- Brown, Anthony Cave (Ed.). 1978. Dropshot: The American Plan for World War III Against Russia in 1957. New York: Dial Press; Richelson, Jeffrey. 1986. “Population Targeting and US Strategic Doctrine.” In Desmond Ball and Jeffrey Richelson (Eds.). Strategic Nuclear Targeting. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 234–249.

- McNamara, Robert S. 1969. “Report Before the Senate Armed Services Committee on the Fiscal year 1969-73 Defense Program, and 1969 Defense Budget, January 22, 1969.” Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 11.

- For a scholarly analysis of and an alternative view to deterrence see: Kugler, Jacek. 1984. “Terror Without Deterrence: Reassessing the Role of Nuclear Weapons.” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 28(3), September, 470–506.

- Kant, Immanuel. 1795. “Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch.” In Perpetual Peace and Other Essays. Indianapolis: Hackett, I, 6.

- Pinker, Steven. 2011. The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. New York: Penguin.

- Rhodes, Richard. 2010. Twilight of the Bombs: Recent Challenges, New Dangers, and the Prospects of a World Without Nuclear Weapons. New York: Knopf.

- Schlosser, Eric. 2013. Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety. New York: Penguin.

- See the documentary film of that title. Trailer: https://bit.ly/2CVRuPJ

- Science Salon podcast episode # 107 with Fred Kaplan and Science Salon podcast episode # 127 with William J. Perry were based on their new books: Kaplan, Fred. 2020. The Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear War. New York: Simon & Schuster; Perry, William J. and Tom Z. Collina. 2020. The Button: The New Nuclear Arms Race and Presidential Power from Truman to Trump. BenBella Books.

- For a striking visual demonstration of every one of the 2,053 nuclear weapon explosions between 1945 and 1998 by the Japanese artist Isao Hashimoto, starting with the Trinity test in New Mexico, where in the world they happened and whom they were sponsored by, see: https://bit.ly/2D20l2o

- 2018. U.S. Nuclear Modernization Programs report. Arms Control Association. August. https://bit.ly/3fQv0yk

- The Nobel Prize committee’s statement on President Obama’s award: https://bit.ly/2WLWr4K Sonne, Paul, Gordon Lubold, and Carol E. Lee. 2016. “‘No First Use’ Nuclear Policy Proposal Assailed by U.S. Cabinet Officials, Allies.” Wall Street Journal, August 12. https://on.wsj.com/3hsKGYR

- Waltz, Kenneth N. 2012. “Why Iran Should Get the Bomb: Nuclear Balancing Would Mean Stability.” Foreign Affairs, July/August.

- Barash, David. 2018. “Deterrence and its Discontents.” Skeptic, Vol. 23, No. 2, https://bit.ly/2EikKkt

- Quoted in Kaplan, op cit., 244.

- Fettweis, Christopher. 2010. Dangerous Times? The International Politics of Great Power Peace. Georgetown University Press.

- Lipton, Judith and David Barash. 2019. Strength Through Peace: How Demilitarization Led to Peace and Happiness in Costa Rica, and What the Rest of the World Can Learn From a Tiny, Tropical Nation. Oxford University Press.

- Shakespeare, William. 1594. The Rape of Lucrece. Available at: https://bit.ly/2ByB5k4

This article was published on August 7, 2020.

Today I received an e-mail from a friend in the UK (Tony) with thoughts on this subject:

“The world was very lucky with the sequence of events surrounding the inevitable invention of nuclear weapons.

Firstly – the right people achieved it first.

Then the opportunity/need to use them arose when only one country had them and that they first became available at the end of a world war.

At that stage they were of the right power to achieve the result and to affect global thinking without ‘overdoing it’.

Had they not have been used until later when several countries had massively powerful weapons and they were then first used at the outset of a new war the world would have experienced a truly horrific catastrophe.”

More insight from Tony in the UK:

1. The US wanted the peace treaty with Germany after WW1 to be much less punitive than that wanted by France and the UK. Had the US had its way perhaps it would had avoided WW2

2. One of the reasons the UK wanted its own H-bomb was the belief that a country as young as the US could not have developed the necessary diplomatic skills and therefore it was vital that the UK should maintain its position at the top table.

3. Once again the US showed its statecraft by giving generous help to the Japanese after the war. I wonder if that would have been the same if the Americans had had to invade the Japanese home islands.

Great discussion. Very seldom do I have the time to plow through all of the commentary, but the individuals who responded to Michael Shermer’s article are obviously well-versed in the topic.

Since I cannot to pretend to be as knowledgeable, I can only say that it is near impossible to justify any situation where a mass amount of people, or even a few, for that matter, die as innocents who may not even agreed with the conditions of war, but merely wanted to go on with their daily lives.

One of the arguments that has always intrigued me is … why the necessity of dropping the second bomb? The surrender was almost inevitable after the first. The devastation and loss of life was so severe that it would take the most hard-hearted of any military official to continue a battle against a cannister that could cause the type of horrific damage that the first bomb did.

Einstein regretted that he ever wrote the letter to convince Roosevelt to move forward with the Manhattan project due to the results of the aftermath.

It becomes an arduous task to justify the necessity of this second bomb, whereas there is some justification for the first bomb with the ability to win the war greater than ‘the war to end all wars’ through shock and awe.

I can’t add more to the discussion other than an emotional response to the dropping of the second bomb. If I were a Japanese citizen trying to live through daily struggles with a home, job and family, and all the streets I traversed most of my life, all the buildings, every sense of what life means disappeared in seconds (and that’s only if I were lucky enough to survive without excruciating wounds and scorched, peeled and missing skin), I could no longer make sense of the meaning of life in any form or manner.

Rebuilding a nation after a war like this becomes meaningless to the people who survived. The second bomb becomes the point at which the question has to be asked: Was Truman and his administrators a ‘butcher’?

No argument can justify the result to those who suffered, and can only be argued philosophically in retrospect by those who attempt to make sense of war in some utilitarian manner.

Nobody wants to be in a gun fight without a gun. Nobody wants to feel helpless. The powers that be conceive of a collective consciousness for which they are responsible, and build bombs to protect us, to make us feel safe, to make us believe that we as a nation hold the bigggest gun under the guise of a nuclear weapon(s), but the whole idea of a bomb being dropped at the calibre of what happened to Japan is almost unthinkable; however, it is hard to imagine that we have fully learned from history; it may be that with the passing of time, the brutality of horrible incidents fades into a mere myth, just a story, and one day, another bomb will drop.

“…why the necessity of dropping the second bomb? The surrender was almost inevitable after the first.”

If you chose not to do the research, please do not make specious claims like this. After Hiroshima, the cabinet could not even agree on terms for a negotiated peace, and that was not going to happen.

Read Frank’s “Downfall”; it took Hirohito demanding his military surrender to do so.

By comparison, the military was willing to sacrifice 20,000,000 Japanese in the hopes of bringing the Allies to the bargaining table.

Perhaps I missed it, but I see no reference to Frank’s “Downfall”.

Michael, did I miss it, or did you?

Here is something I’ve always been puzzled by and have never seen addressed. 16 July, 1945 is always characterized as a red-letter date in history; the birth of the nuclear age, and the progenitor of important policy decisions such as cooperation with the Soviets in the far east at the end of the war. Post this date, we knew we had a war-winning weapon, which was communicated to national command authorities. And one would think that, as our desire was to bring the conflict to a halt as soon as possible, we would use the design proven at the Trinity test in the first combat employment (Fat Man, the plutonium implosion design).

Yet as we all know, the first device employed in combat was the uranium gun-assembly design (Little Boy), which design was never tested beforehand. That this was done strongly suggests that the Manhattan scientists and engineers were very confident that we already had a successful design ready for use quite some time prior to 16 July, 1945. My question: Was this confidence ever communicated to national command authorities prior to Trinity, and if not, why not?

“My question: Was this confidence ever communicated to national command authorities prior to Trinity, and if not, why not?”

First, keep in mind that the tech was ‘untested’ in the extreme, and even if it worked, the Allies had no assurance it would end the war, while time was of the essence. Allied casualties were rising on an exponential curve as the fighting approached the home islands, as were Japanese deaths and those on the Asian littoral. Again, please read Frank, “Downfall”

What you refer to was no secret to anyone involved with (and cleared regarding) the nukes; pretty sure Rhodes makes this clear.

The U device (Little Boy) required material which turned out to be very difficult to ‘refine’, while the design was so simple, it was presumed (and proved to be) ‘fool-proof’. But the refining process(es) were so difficult and failure-prone that it would be quite a while before the Allies could deliver another Little Boy.

Pu production was easier by orders of magnitude, and once the implosion tech (Trinity) was shown to function, that was the chosen avenue.

Remember that, at the time, no one knew which alternative was to prove both successful and ‘economical’ (In time, especially), so the effort was pushed forward on parallel lines of investigation.

But, you can be sure, the results of either alternative were NOT (edit) hidden from anyone who should have known.

Aside: As a result of geography, the claimed death tool was higher in Hiroshima.

‘Nother aside:

“The U device (Little Boy) required material which turned out to be very difficult to ‘refine’, while the design was so simple, it was presumed (and proved to be) ‘fool-proof’.

U 235 is what is required for a Little Boy; it takes but a primitive technological base to produce that material, albeit slowly through centrifuges; see both NK and Iran, which fuel my doubt that the bottle can be closed.

If my understanding of history is correct the genesis of the Manhattan project was the fear Germany was already in their own fission weapon project. Leo Zsilard convinced Einstein with a written plea to FDR, so to beat the Nazis to the “fission bomb gate. ”

After Germany’s surrender most of the M-project physicists were against any further development.

Would FDR pursue the same path as Truman? You can play a lot different contingencies including many of us who had enlisted fathers and what a Japanese invasion “worse hell” it could bring. Truman made the lesser of the evils though perhaps it could be argued the decision of which other cities or installations.

“Would FDR pursue the same path as Truman?”

You have that backwards; Truman became POTUS (supposedly) accidentally, and by criminal negligence on FDR’s part, had near zero briefings on the issues surrounding WWII, the largest conflict in human history.

FDR had already ‘made the decision’ by default; Truman would have had to move mountains to deviate from FDR’s ‘decision’.

The dropping of the atomic bombs in 1945 was unnecessary. I recommend the reading of Rishard Rhodes The Making of the Atomic Bomb, especially Chapter 19 “Tongues of Fire”.

The Japanese court was well aware of the destructive power that the new American weapon possessed. They were prepared to surrender, but the Potsdam declaration insisted on ‘unconditional surrender’ and the Japanese rejected this, insisting on a guarantee that the Emperor would remain on his throne.

Churchill was particularly insistent on this demand for unconditional surrender and did not appreciate the fanatical devotion of the Japanese to their Emperor. This mistake is rarely discussed in Britain due to the reverence in which Churchill is held.

Simply by granting this one exception, guaranteeing the continuation of Emperor Hirohito as Head of State in the Allied terms of surrender would have resulted in Japanese capitulation without the nrrd to drop Fat Man and Liitle Boy.

“Simply by granting this one exception, guaranteeing the continuation of Emperor Hirohito as Head of State in the Allied terms of surrender would have resulted in Japanese capitulation without the nrrd to drop Fat Man and Liitle Boy.”

Wrong.

You need to read “Downfall”.

On July 20 (merely two weeks before the Hiroshima bombing), this specific condition was the subject of a cable discussion between Sato (the Ambassador to Russia, who was supposedly trying to enlist Russian assistance) and Togo (the Prime Minister). Togo categorically rejected that exact sole condition as bait for negotiation, let alone surrender.

Japan was nowhere close to surrender.

Suggest a review of our CIA’s records, which agree with Japan’s, Russia’s, and the Vatican’s…who had been seeking an armistice on Japan’s behalf since JANUARY.

https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/kent-csi/vol9no3/html/v09i3a06p_0001.htm

Very interesting indeed! Also very clear in establisting the veracity of or your claims!

I’m sure an intellect of your caliber might possilbly understand that there was no CIA at the time, right?

Suggest you read Downfall and admit a proposed, hoped-for, wanna-be, gee-could-we-maybe “armistice” is irrelevant.And that you really shouldn’t make an ass of yourself

See the article in the September 2020 Scientific American by Science Historian Professor Naomi Oreskes and History Professor Erik M. Conway. Referring to the American justification of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombing, they write (p.44) “We now know that this story was a postwar invention intended to stave off criticism of the bomb’s use, which killed 200,000 civilians”.

This was a heavily nuanced article and I commend Dr. Shermer for writing it. It is especially relevant now that we have the dubious opportunity to replace our nuclear arsenal for “only” about 1.3 trillion taxpayer dollars. *cough* What a steal! .. and I mean that in a very literal fashion. (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Renovation_of_the_nuclear_weapon_arsenal_of_the_United_States for details.)

I thought it was common knowledge that leadership in the USA dropped the bombs because Russia (well, the USSR) was already on their way over- and we didn’t feel like sharing both credit and war prizes with them. The Soviets had killed 80% of of Nazi combatants and it made both the UK and USA look weak. They also had suffered orders of magnitude more than the UK/USA in terms of soldiers lost. To be fair, we joined the war rather late due to our isolationist stance and also enormous amount of Nazi support/sympathy in our country- which is why we turned the Jews away when they arrive after the war.

As this is skeptic.com; please take my words with a grain of salt. I gained the above perspective not from a historian but a physicist I used to dine with, George Smoot. (He did win the Nobel Prize, but that doesn’t mean he has a better grasp of History.) From what I can tell, however, his story checks out.

Greed and a desire for social esteem motivated dropping the bomb; and perhaps a little bit of vengeful thinking- because of Pearl Harbor, obviously. It wasn’t as if Japan was in any shape to harm the USA when we dropped the bomb- they had lost almost the entirety of their naval fleet and had almost uhm.. zero Zeros (their main fighter airplanes) left. Its a little bit odd that Dr. Shermer didn’t mention this perspective, which is fairly common among Japanese, Russian, and many US war historians. Perhaps I overlooked it due to speed-reading.

Anyway, the nukes didn’t kill *nearly* as many as our firebombing campaign did. According to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Air_raids_on_Japan

we killed between 241K and 900K by fire; mostly civilians. Sort of makes the nukes seem less than relevant.

Our tactic was to hit the firemen after we dropped the first round of thermite- that way we ensured a maximal amount of civilian deaths, as the fires would go on uncontrollably due to their cities being made out of wood. Our belief at the time was that this would scare the citizens into pressuring Hirohito to sign. To a degree it worked; he didn’t believe that he or Japan had a religious “authority from Heaven” at that point, if he ever had. The citizens believed he was essentially a god, and the very first time they heard his voice was in his surrender message. (Which had an incredible story behind it that I will leave you to find, if you wish.)

I sorta come at this from a different angle- What if Truman had NOT dropped those two bombs?

The war may have dragged on until either –

Lemay had flattened Japan into a pe-history state, including millions possibly killed on all sides.

Or-

Japan may have (un)conditionally surrendered after a few weeks more bombing, with no doubt Hiroshima and Nagasaki being flattened with conventional weapons, and a million or so Japanese men, women and children BBQed, “with flesh dripping off their bones” etc as the atomic-bomb survivors were prone to say.

If you had asked any survivors of the Tokyo, Hamburg, Dresden or other large Axis city, they would probably have said the same thing. Alas, the Press was/is more interested in the victims of this new technology. But I digress.

But, would the nuclear bombs then have been locked up and the technology forgotten? No, starting with Teller and Ulam, much more powerful bombs were already in the pipeline. And they were being built by both cold war sides. Sooner or later someone would have used one or more of these H-bombs on a city. “Hey! Let’s see what this does!”. There was no example of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to soberly think about, and fall back upon.

What would have followed would be anyone’s guess.

In this sense, these two cities were sacrificial lambs- martyrs to the MAD nuclear standoff that was gradually developed over the next 15-20 years, and somehow is still keeping the peace today.

I would just add a few thoughts to this excellent overview of the issues involving nuclear weapons.

As to Truman’s decision to use these awful weapons, critics should be aware that there were other circumstances at play. For example, the Soviet Union had run the Japanese out of Manchuria and reportedly had a million-man army ready to invade the Japanese mainland. But they were stuck because they lacked enough ships to launch an invasion. It would be a world-changing event if they did. Stalin wouldn’t care how many died. But the Soviets were still our allies so we kinda kept that information under wraps.

Of course, this tragedy could have been avoided altogether if the Japanese had capitulated. They, in fact, had sued for peace, but were unwilling to accept an unconditional surrender. They were intransigent about maintaining their honor. Death was more honorable than defeat. Testimony to that is the fact is that it was a week after the Nagasaki bomb was dropped that they finally gave in. And even then the condition, which the allies accepted, was to exempt the Emperor from being charged with war crimes.

After the war came the Tokyo trials, which, like the Nuremberg trials, were to prosecute those responsible for crimes against humanity. For those latter-day moralists who condemn Truman’s decision, reading some of the testimony from those trails might be informative. Their treatment of the Chinese was pretty horrific, as best described in the book, “The Rape of Nanking.” Even today, the Chinese leaders are pretty cool toward their Japanese counterparts.

In any case, much of the inhuman treatment of the POW’s and the citizens of China, Korea, the Philippines by the Japanese was well known even while the war was underway.

Meanwhile, back in this country, Americans were tired of war. They were still under a ration economy. And war bonds were becoming harder and harder to sell.

These are just some of the challenges President Truman had to take into account in making his historic decision. Given the circumstances at the time, I believe any reasonable person would came to the same conclusion – retrospective moralizing notwithstanding.

^+1

Sadly, Dr. Shermer’s fact, statistic, and number based refutation of those who denounce the use of the two A-bombs will do as much to change their minds as Professor Mary Lefkowitz’s Not Out of Africa did of Afrocentrists’, Professor Deborah Esther Lipstadt’s Denying the Holocaust did of holocaust deniers’, Judge John E. Jones’ decision in the Dover School District Trial did of Creationists’, and Richard Dawkins’ The Blind Watchmaker did of Intelligent Designers’. In a word: Nothing.

For years there were credible claims that the casualty predictions were inflated, matched with speculation as to cause(s). As it happens, those were based on incomplete intel records.

Once the complete records were released, it was shown that those claims were NOT credible; Frank (“Downfall”) was AFAIK the first to make use of them as applied to the claims; his research is every bit as good as his coordination of various sources and then his analysis of what that stuff means.

But you are correct; much as Ehrlich’s “Population Bomb” BS continues to get ink in spite of every bit of evidence to the contrary, the hope that we could have waved some sort of a magic wand and gotten a surrender will endure.

Small point, and I hope it can be corrected in the text, but trinitite did not “fill” the crater (nor could it even nearly) but lined it to a depth of a couple of cm. Most of it is in fact gone, having been collected or sold as souvenirs.

Incidentally, I frequently have read assertions that the bombs were dropped out of malice or the desire for destruction etc, and that the lives lost were out of proportion to any that might have been saved, because the Japanese were about to surrender anyway; however I never swallowed any of that because it did not check out with the rest of my reading of that period. My personal opinion, whether it was the intention or not, was that it probably saved more Jap lives than allied lives

Selfishly, I have not been troubled by the decision to drop the bombs on Japan. My father was in combat in the European Theater during World War II. Having fought from Normandy into Germany, he did not have enough “points” to go home and was on a ship bound for the invasion of Japan when the war ended.

But as The Washington Post reported this week, tens of thousands of people have died since then from radiation from nuclear testing. And accidents.

My father came home from the war and worked in Oak Ridge, Tenn., site of part of the Manhattan Project, and still a processor of nuclear fuels. After he retired, he died of lung cancer, likely caused by exposure to radiation, according to a settlement we received from the government.

He was spared the invasion, but died of the weaponry that prevented it.

The figures for deaths after the bombs and the immediate after math (say a year or two) are generally speculative. It is hard to say how many of those really did result from the bombs, and in fact how many were from “natural causes”, smoking, old age etc.

And even at that, a few tens of thousands added to the direct deaths would have been a drop in the bucket compared to the lives saved, both Japanese and allied. They also were a fraction of the rest of the Japanese deaths throughout the war, not to mention allied civilian deaths.

Really, the nukes might have been horror weapons, and may have been war winners whether necessary or not, but they were not out of line with their times and needs. Suppose the opposition had got the bomb first, what do you suppose the outcome might have been? Gentle admonitions to surrender?

What do you think it might be today if say NK got workable bombs and delivery systems and thought that they could use them with a reasonable chance of silencing the first world?

Selfish of you? Compared to whom?

And lung cancer? OK, could be. But compare that probability to the possible effect of any smoking he might have done. I have lost several friends to that in my life, and do not live near any test sites.

??? Why are Americans always bringing North Korea as a bogeyman?

The whole “First World”? Gimme a break!

“But.. OOH! They might hit Seattle!”

Yeah? So? If they launched even a few H-bombs towards the USA, the DPRK would become a no-man’s landscape covered in… what’s that stuff called? Trinitite?

South Korea (what was left of it) would effectively become an island. And General MacArthur’s Korean nuclear isolationist dream would finally have been effected.

“??? Why are Americans always bringing North Korea as a bogeyman?”

Care to offer a cite to defend your claim? I doubt it.

Alas, Doubting Thomas-

Citations? There are far too many. Or at least were, in the popular press, before Trump persuaded Little Rocketman to stop testing nukes.

You don’t follow the “news”?

Oh. Here’s a sample. Just click.

Every day there was an article or a headline somewhere about how the DPRK was developing nukes and missiles that could “now hit Seattle”.

Perhaps this news was blacked out in the rest of the USA.

Anyhow… prediction: Once this November melodrama is finished, expect li’l Kim to resume these tests, particularly if Biden et al are elected.

My apologies for the schadenfreude. I’m a Canadian living ~4500 KM east of Seattle (and Vancouver BC ). ;-)

One factor that I think deserves more consideration is the institutional inertia of the Manhattan Project compared with Truman’s weak status in his first few months as president. The scale of the Manhattan Project was vast and that amount of investment makes it politically difficult to not make use of it. We remember Truman as the president who fired MacArthur but after FDR’s death, there were widespread concerns about Truman. FDR had kept him out of the loop – and some advisors took advantage of that. The resulting bungling of diplomacy contributed to starting the Cold War and strained US-British relations.

At the time the decision had to be made, could Truman really have said “No” to the use of the atomic bombs? There would be a reckoning for the secret Manhattan Project because so much had been spent on not one bomb project but two: the Uranium and Plutonium projects. FDR may have decided to go ahead with the project but Truman would have to answer for it. To make the situation worse, Truman was ignorant of the Atomic bombs when he became president – indeed, Stalin knew more about these bombs when FDR died than Truman did. The sheer scale of the atomic bomb projects made it almost guaranteed that if the bombs worked they would be used. Only a leader with the political capital of FDR would be able to halt that juggernaut.

Truman’s insistence that he decided to drop both bombs may be more of a case of jumping in front of a parade and calling yourself the Drum Major.

Maybe the real debate should be: should we be spending so much on weapons when human nature is to use things when we pay a lot for them?

“Truman’s insistence that he decided to drop both bombs may be more of a case of jumping in front of a parade and calling yourself the Drum Major.”

Any history of the issue from Rhodes to Frank makes it clear that FDR had already ‘made the decision’ affirming their use (as much as that career politician ever ‘made a decision’). As the inheritor of FDR’s ‘decisions’ and an “accidental” POTUS), Truman would have had to move mountains to provide sufficient reason to deviate from that path.

It doesn’t help that FDR knew, (as did his lying medical staff) that he was circling the drain prior to his election, and yet he remained criminally negligent in preparing his successor regarding the issues of the greatest conflict in world history; that narcissism is breathtaking!

If there was an alternative, FDR’s negligence removed any possibility of Truman exercising that option.

“Maybe the real debate should be: should we be spending so much on weapons when human nature is to use things when we pay a lot for them?”

That’s an issue separate from the end of WWII, and currently, defense (one of the proper activities of a federal government) represents a small amount of the budget.

Maybe we should be spending less on other matters?

Some years back, I deplored the use of nukes. After more research, it seems they were the most human alternative to ending WWII

This is a very disappointing essay by Mr. Shermer, whom I’ve always admired. it is a amoral rationalization of what was, while not the “most unspeakable act in history” per Chomsky, but was most certainly a single unspeakable act.

Shermer downplays its impact by opening with false statistics on fatalities and later giving ones closer to the truth, no statistics on the lasting injuries and deaths of Japanese civilians from radioacivity and other injuries some possibility genetic.

He wants to put this immoral act in context as if the widespread bombing of 66 Japanese cities killing mostly civilians is somehow justified. They were all war crimes by International Law. And these bombing with the cute names were in blatant disregard of those laws. It’s all “all’s fair in love and war” amoral philosophy.

He dismisses the bombing of an isolated uninhabited island as an “unlikely” deterrent. What about the bombing of the many Japanese island military installations such as Shimshu Mr. Shermer? There were many others available so even more could have made the point to the Japanese leadership.

Towards the end of World War II the island was strongly garrisoned by both the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) and Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). A garrison of over 24,500 men reinforced by sixty tanks was garrisoned on Shumshu in nine locations centered around Kataoka. All coastal areas suitable for enemy amphibious landings were covered with permanent emplacements and bunkers. There were also squadrons of airplanes.

This island was active after the atomic bombings until the Soviets

captured it in late August of 1945.

Wouldn’t that have been worth trying Mr. Shermer to avoid the death of an estimated 200,000 to 300,000 people?

Throwing up a lot of hypotheticals about future casualties doesn’t make the case for the bombings, they should have been the absolute last resort. They weren’t.

Civilians are always the greatest casualties during wars but that doesn’t mean that every effort shouldn’t be made to avoid them.

But these bombings and many others during World War II were

deliberate attempts to kill civilians not military targets.

One can’t justify this.

Bye bye Skeptic

Hugh Giblin

First, I’d suggest you read both “Downfall” (Frank), and “Hell to Pay” (Giangreco); you seem to be misinformed.

Your suggestion that an island be bombed in the hopes of impressing the leaders ignores the fact that a CITY was leveled, it had not the desired effect.

You are welcome to all the fore-lock tugging which makes you happy, but fantasizing that this or that might have done the job absent one shred of evidence does not make the case to this skeptic.

Japan in August 1945 still held most of the territory it had captured in Asia and Indochina. Emperor Hirohito felt they could secure favorable terms for ending the war that would include the continued possession of some of their territorial gains.

August 6th and 9th changed this mindset. After years of being taught that they were to fight to the last breath, Japan’s citizens on August 15th heard their Emperor tell them they must “pave the way for a grand peace for all generations to come by enduring the unendurable and suffering what is unsufferable” since “the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable”. Emphasizing that he grasped the realities of the new atomic age, he added that continuing to fight “would lead to the total extinction of human civilization”.

Diplomacy would not have led the Emperor and his people to “endure the unendurable” to end the carnage. Only the atomic bomb or the invasion of Japan would have ended the war with acceptable terms. The atomic bombs did it with a minimum of American casualties. An invasion would have cost a minimum of half a million Japanese lives.

The “bombs invented by Americans” have continued to save lives by putting limits on warfare. If the bombs had not been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they almost certainly would have been used in another 20th century conflict. Emperor Hirohito said in September 1945 that “the peace party did not prevail until the bombing of Hiroshima created a situation which could be dramatized”. The pictures of the mushroom clouds and the devastation of the Japanese cities have an indisputable impact that will be with all future generations.

One must be careful when wishing that past events had gone differently. The American occupation and the transformation of Japanese society after WWII borders on being miraculous. If peace had been obtained any other way, there is no guarantee of the same outcome.

Thanx. You said it much more eloquently (if not succinctly) than I did.

Thank you.

” If peace had been obtained any other way, there is no guarantee of the same outcome.”

Nor is there the slightest possibility that the death toll, Japanese, Allied and non-combatant, would have been by any other means, as economical as the result of the nuclear bombing.

For years, I have asked those like Hugh Giblin to propose an alternative which would realistically serve with less loss of life. The responses are uniformly untruths (‘The Japanese were near surrender’), or fantasies (‘We could have convinced them by dropping it somewhere else’); those and others are better addressed in Frank’s “Downfall” than I am capable of here.

In fact, I’d go so far as to suggest that if you have not read “Downfall” or matched his research, you really ought not propose alternatives at all.

Again, after years of reading and consideration, it’s impossible to escape the conclusion that those two bombs represent the most humane option to ending WWII. (sp correctly this time)

As an aside: Regarding the desire to ‘ban the bomb’, I’m very doubtful of the possiblity of jamming that genie back in the bottle. A kid isn’t going to make one in the HS metal shop, but it doesn’t take much industrial base and sufficient bribery money to accomplish the goal.

Hiroshima 1945: Behind The U.S. Atom Bomb Atrocity

BY FRED HALSTEAD

On Aug. 6, 1945, and again on August 9, the U.S. government dropped the first and second atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Tens of thousands of people died instantly, with thousands more dying later. This year marks the 50th anniversary of that atrocity.

The following article appeared in the Jan. 25, 1965, issue of the Militant under the headline “What the Record Shows: U.S. Guilt at Hiroshima.” The author, Fred Halstead, was a longtime leader of the Socialist Workers Party.

As the SWP’s candidate for president in 1968, Halstead took a trip around the world, visiting Japan, South Vietnam, India, Egypt, West Germany, France, and Britain. In Japan he attended several peace conferences, addressing a session of the Japan Conference Against A- and H-Bombs on August 6 in Hiroshima.

That Japan was “truly making sincere requests for peace,” before and at the time of the Hiroshima A-bomb, is an undisputed fact of history. It is so well established that even popular history books and standard reference works recently published in this country cannot ignore it.

The obvious implications of the fact are so damning to the moral position of the American capitalist power structure and so unpleasant to the American people generally, however, that the fact is not often squarely faced in this country, even by many pacifist critics of the government’s nuclear warfare policies. In the popular histories and reference works, it is generally glossed over with the briefest, most off-hand mention – after the style of West German textbook references to Nazi crimes – as if the unpleasant fact could somehow be buried and forgotten if it is given the low-key treatment.

And indeed the general impression still exists in this country (but not abroad) that somehow the dropping of the A-bombs on Japan caused the end of the war and eliminated a bloody invasion of the Japanese home islands, thus saving more lives than the A-bombs themselves snuffed out. This is a lie manufactured and spread in the first place by President Truman and British prime ministers Churchill and Attlee, who took responsibility for the decision to drop the bombs. It is nothing but the official trumped-up alibi for one of the most shocking and unjustified war crimes in all human history.

What are the facts? This is what the Encyclopedia Britannica (1959 edition) has to say: “After the fall of Okinawa [on June 21, 1945], [Japanese Prime Minister] Suzuki’s main objective was to get Japan out of the war on the best possible terms, though that could not be announced to the general public… Unofficial peace feelers were transmitted through Switzerland and Sweden… Later the Japanese made a formal request to Russia to aid in bringing hostilities to an end.”

The Britannica then completes its coverage by saying that Russia rebuffed the Japanese overtures because it didn’t want the war to end before it was scheduled to invade the northern areas occupied by Japan. What the Britannica fails to mention is that these Japanese overtures were known to Washington because the dispatches between Foreign Minister Togo in Tokyo and Japanese Ambassador Sato in Moscow were intercepted by the United States.

The entire affair is documented in the Hoover Library volume Japan’s Decision to Surrender, by Robert J.C. Butlow (Stanford University, 1954). Butlow quotes the dispatch that was received and decoded in Washington on July 13, 1945:”Togo to Sato…Convey His Majesty’s strong desire to secure a termination of the war…Unconditional surrender is the only obstacle to peace.” These requests continued through July.

Butlow documents that Washington knew the one “condition” insisted upon by the Japanese government was the continuation of the emperor on his throne and the symbolic recognition this implied of the Japanese home islands as a political entity. As it turned out this was exactly the “condition” that was granted when the peace was finally signed after the A-bombings August 6 and 9.

If the U.S. government knew as early as July 13 that the leading circles in Japan were seeking peace on those terms, why didn’t it pursue this possibility for peace instead of ignoring it and proceeding with the A-bombings? There is simply no satisfactory answer to this question from the point of view of the military demands of ending the war – even on U.S. imperialist terms – and saving soldiers’ lives.

Twice guilty

As Hanson W. Baldwin, the New York Times military analyst, said in his book Great Mistakes of the War (1949):

“Our only warning to a Japan already militarily defeated, and in a hopeless situation, was the Potsdam demand for unconditional surrender issued on July 26, when we knew the Japanese surrender attempt had started. Yet when the Japanese surrender was negotiated about two weeks later, after the bomb was dropped, our unconditional surrender demand was made conditional and we agreed, as [Secretary of War] Stimson had originally proposed we should do, to continuation of the Emperor upon his imperial throne.

“We were, therefore, twice guilty. We dropped the bomb at a time when Japan already was negotiating for an end of the war, but before these negotiations could come to fruition. We demanded unconditional surrender, then dropped the bomb and accepted conditional surrender, a sequence which indicates pretty clearly that the Japanese would have surrendered, even if the bomb had not been dropped, had the Potsdam Declaration included our promise to permit the Emperor to remain on his imperial throne.”

Why, then, did the United States drop the bombs? One of the few writers who claims to believe the official alibi is Robert C. Batchelder, author of the well-documented The Irreversible Decision (1962). Even Batchelder admits: “It seems clear that had the [U.S.] attempt to end the war by political and diplomatic means been undertaken sooner, more seriously, and with more skill, the decision to use the atomic bomb might well have been rendered unnecessary.”

Batchelder explains the affair away by attributing it to U.S. diplomatic inefficiency and a tendency in U.S. leaders to deal with the war in purely military terms and neglect political aspects. But the evidence indicates the final A-bomb decision was made precisely for political reasons.

Indeed, some top U.S. military men – including Eisenhower and the chief of staff of the U.S. armed forces at the time, Adm. William D. Leahy – declined to support use of the bomb. In his book, I Was There (1950), Leahy says: “it is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons.

“It was my reaction that the scientists and others wanted to make this test [!] because of the vast sums that had been spent on the project. Truman knew that, and so did the people involved. However, the Chief Executive made the decision to use the bomb on two cities in Japan.”

Live targets

This “test” on Hiroshima and Nagasaki cost, by the conservative American estimates, 110,000 dead and as many injured; and, by Japanese estimates, twice that many. The evidence strongly indicates that one major motivation of the A-bomb decision was precisely to test the bomb on live targets, so as to confront the postwar world with the proven fact of overwhelming U.S. military superiority. It also established the fact that U.S. imperialism not only had the bomb but had the ruthlessness to use it.

The haste with which the bomb was used indicates that the U.S. purposely ignored the Japanese peace requests (which were known in Washington on July 13) in order to drop the bomb before the war ended. No one was sure the bomb would work until July 18 when it was tested in New Mexico. The only other two bombs in existence were quickly dispatched to the Pacific base and were dropped on August 6 and 9. This haste is unexplained by combat problems. By that stage of the war U.S. bombers and ships encountered no serious resistance and no U.S. troop attacks were scheduled until November 1, so the haste was not necessary to “save American lives.”

One of the most thoughtful works on the subject is that by the British nuclear scientist, P.M.S. Blackett, entitled Fear, War and the Bomb (London, 1949). Blackett points out: “If the saving of American lives had been the main objective, surely the bombs would have been held back until (a) it was certain that the Japanese peace proposals made through Russia were not acceptable, and (b) the Russian offensive, which had for months been part of the allied strategic plan, and which Americans had previously demanded, had run its course.”

Bomb aimed against Soviet Union

This last is the final piece in the puzzle. It is Blackett’s well-founded thesis that one reason for the haste was to drop the bomb before the Russians entered the war against Japan. The allies had already agreed at Yalta that the USSR would attack Japan three months after Germany surrendered. Stalin had notified the United States that the Russian armies would be ready for that attack on schedule, that is, August 8. The bomb was dropped on Hiroshima August 6.

In another book by Blackett, Atomic Weapons and East- West Relations (London, 1956), the scientist discusses the later feelings of some of his American colleagues who had been involved in the decision to use the A-bomb:

“The opposition between 1949 and 1951 of so many atomic scientists to the H-bomb program must, I think, be taken as the price the American Government paid for lack of candor in 1945. If the scientists had been told that Japan had been essentially defeated and was suing for peace, but that the dropping of the bombs won for America a vital diplomatic victory, since it kept the Soviet Union out of the Japanese peace settlement and so avoided the difficulties and frictions inherent in the German surrender, I expect most would have accepted, however reluctantly, the practical wisdom of the act. They were not told this, but they were told that the bomb saved untold American lives. When they later learnt that this was rather unlikely, many of them must have begun to fear that their government might not be able to resist some future temptation to exploit America’s atomic superiority…”

To sum up: That Japan was defeated and suing for peace before the bombs were dropped is a fact established beyond doubt. The motivations of U.S. rulers in dropping the bombs anyway is, of course, a disputed question. But the evidence utterly fails to support the official alibi that it was done to avoid costly battles. On the contrary, the evidence overwhelmingly indicates that the civilian populations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were murdered, not to end World War II, but to launch what later came to be known as the cold war. //:0 //:0

Sure, it is a fact that dropping the bombs had the advantage of sending a message to the Soviet, but this is in no way the primary reason the decision was made. Japan’s negotiating for peace had demands far beyond keeping their Emperor in power. The current revisionist denial that the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki saved far more lives than were taken is typical of those who cherry pick facts and fail to look for the whole truth.

Oh, goody! One more anti-bomb idiot!

Let’s start by mentioning I’ve read Halstead’s screed along with Alperovitz “The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb”, and Walker’s “Prompt and Utter Destruction”. All of them offers claims that ‘the US was really, really bad to do this and here’s why I feel that way’, followed by cherry-picked ‘facts’ which are not; they are more opinions. I suggest you read some sources which offer facts rather than emotions.

Here we go:

“That Japan was “truly making sincere requests for peace,” before and at the time of the Hiroshima A-bomb, is an undisputed fact of history”

Supported by other claims amounting to propaganda and no cites, probably because it it totally unsupported. Simply: Bullshit. “Requests for peace” =/= surrender; do you find that surprising?

“What are the facts? This is what the Encyclopedia Britannica (1959 edition) has to say: “After the fall of Okinawa [on June 21, 1945], [Japanese Prime Minister] Suzuki’s main objective was to get Japan out of the war on the best possible terms, though that could not be announced to the general public… Unofficial peace feelers were transmitted through Switzerland and Sweden… Later the Japanese made a formal request to Russia to aid in bringing hostilities to an end.”

So we have “peace feelers’ where surrender is the condition. I hope you’re beginning to get embarrassed.

”Togo to Sato…Convey His Majesty’s strong desire to secure a termination of the war…Unconditional surrender is the only obstacle to peace.” These requests continued through July.”

So the only obstacle to surrender was the the requirement of surrender? Hmm. I hope your face is getting red by now.

“Butlow documents that Washington knew the one “condition” insisted upon by the Japanese government was the continuation of the emperor on his throne and the symbolic recognition this implied of the Japanese home islands as a political entity.”