50th Anniversary Tribute

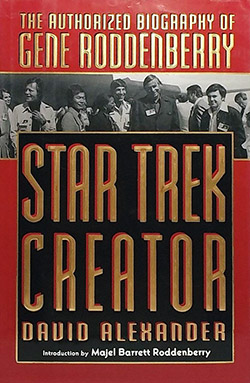

Star Trek was launched in the US on September 8, 1966, 50 years ago tomorrow, which also happens to be Michael Shermer’s birthday, so he remembers it well—hooked on the show and the concept and all that it stood for from the beginning. Shermer penned this essay in 1994 upon the publication of his friend David Alexander’s biography: Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry. David was a humanist and skeptic and deeply involved in both movements when Roddenberry chose him as his biographer. As such, David was granted access to Roddenberry’s private archives, and he treated his charge with respect, even while revealing the man’s very human flaws. Shermer used the occasion to consider the role of the individual—the hero even—in history, and how one person really can make a difference, which surely Gene Roddenberry did.

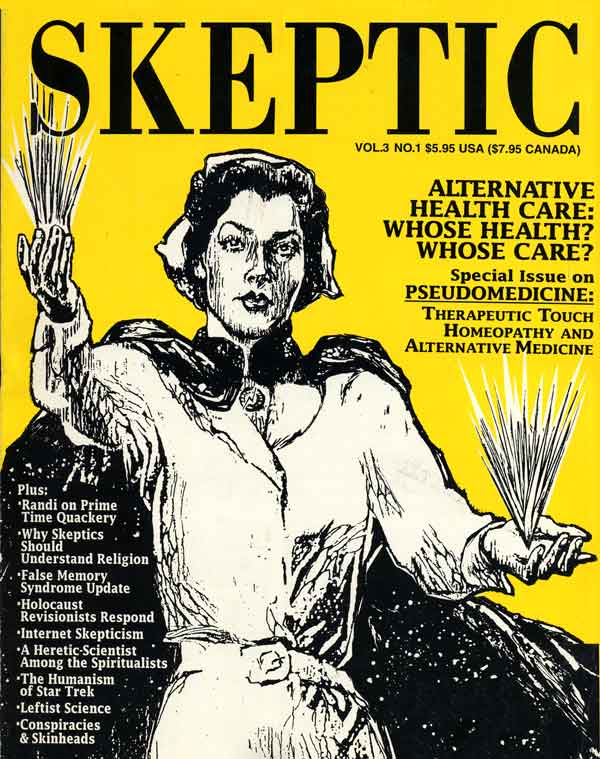

A version of this tribute article was originally published in Skeptic magazine 3.1 in 1994, under the title “The Thinker on the Edge of Forever,” and republished in Shermer’s 2005 book Science Friction, a collection of articles and essays from the previous decade. Read Michael Shermer’s bio at the end of this article.

Historians and biographers have explained the origin of the heroic in two dramatically different ways. At one end of the spectrum heroes are “great men”—seminal thinkers, brilliant inventors, creative authors. At the other end heroes are historical artifacts of their culture—ordinary people thrust into positions of power and fame that might just as well have gone to others. The first archetype is represented by Thomas Carlyle in his Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History: “Universal History, the history of what man has accomplished in this world, is at bottom the history of the great men who have worked here. Worship of a hero is transcendent admiration of a great man.” The second archetype is seen in such Marxist writers as Friedrich Engels: “That a certain particular man, and no other, emerges at a definite time in a given country is naturally a pure chance, but even if we eliminate him there is always a need for a substitute, and the substitute…is sure to be found.”

Although such polarities are held by relatively few, the central claims of both contain an element of truth. History’s heroes may be great individuals, but all individuals, great or not are—indeed must be—culturally bound; where else could they act out the drama of their heroics?

In this sense, history and biography may be modeled as a massively contingent multitude of linkages across space and time, where the hero is molded into, and helps to mold the shape of, those contingencies. For Sidney Hook, in his classic study of The Hero in History, a hero is “the individual to whom we can justifiably attribute preponderant influence in determining an issue or event whose consequences would have been profoundly different if he had not acted as he did.” History is not strictly determined by the forces of the weather or geography, demographic trends or economic shifts, class struggles or military alliances. The hero has a role in this historical model of interacting forces—between unplanned contingencies and forceful necessities.

Contingencies are the sometimes small, apparently insignificant, and usually unexpected events of life—for want of a horseshoe nail the kingdom was lost. Necessities are the large and powerful laws of nature, forces of economics, trends of history—for want of 100,000 horseshoe nails the kingdom was lost. Elsewhere I have presented a formal model describing the interaction of these historical variables, summarized in these brief definitions: Contingency is taken to mean a conjuncture of events occurring without perceptible design; Necessity is constraining circumstances compelling a certain course of action. Leaving either contingencies or necessities out of the biographical formula, however, is misleading. History is composed of both, therefore it is useful to combine the two into one term that expresses this interrelationship—contingent-necessity—taken to mean: a conjuncture of events compelling a certain course of action by constraining prior conditions.

Contingent-necessity is actually an old concept in new clothing. The Roman historian Tacitus was uncertain “whether it is fate and unchangeable necessity or chance which governs the revolutions of human affairs,” where we have “the capacity of choosing our life,” but “the choice once made, there is a fixed sequence of events.” Karl Marx offered this brilliantly succinct one-liner (from The Eighteenth Brumaire): “Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly found, given and transmitted from the past.”

A question arises from this: Can we find a repeatable pattern in historical sequences that demonstrates when and where contingencies and necessities will dominate in the life of an individual? Contingency and necessity vary in both influence and sequential position within any given historical sequence according to what is called the model of contingent-necessity, which states: In the development of any historical sequence the role of contingencies in the construction of necessities is accentuated in the early stages and attenuated in the later.

To tell the story of someone’s life, then, the biographer must understand not only the contingencies and the necessities of the individual’s history, as well as the history around him, but the nature and timing of their interaction. The biographer must see which conjunctures of events compelled certain courses of action (contingencies constructing necessities), and which constraining prior conditions determined future actions (necessities creating outcomes). In other words, we must know not only the life and the times of the person, but how this life and those times interacted, when, and in what sequence to produce the outcome in question. As an exemplar of both biography and this particular philosophy of biography, I suggest the life of Gene Roddenberry told by his biographer David Alexander, who has skillfully reconstructed the contingencies and necessities—the life and times—of the creator of Star Trek. And, as I hope to show, Gene Roddenberry has done the same through his fictional starship voyages in his humanistic vision of humanity’s future.

Reviewing episodes of the original series of Star Trek today one is struck by the almost absurdly simplistic design of set and costumes (made worse by the cartoonish colors of the 60s-era clothing). Yet the show resonated across generations to become one of the most remarkable television phenomena in the medium’s history. The reason is relatively simple: Roddenberry was an enlightened storyteller who baldly addressed the deepest issues in science, religion, philosophy, politics, and current events. He was adept at placating television executives and advertisers, while simultaneously maintaining a commitment to promoting science and humanism. David Alexander was one of Gene Roddenberry’s closest friends, and was hand-picked by Roddenberry to be his authorized biographer. One might thus expect a dearth of dirt. But no, it is here, warts and all. Although to be fair, additional warts have been added by others since the original publication of Alexander’s biography in 1993. The entertainment journalist Joel Engel, for example, has painted a far less flattering portrait of Roddenberry in his 1994 biography, Gene Roddenberry: The Myth and the Man Behind Star Trek. For me, anyway, little of this dirt matters in the overall impact of the man and his humanistic philosophy. Knowing that he sometimes took credit that was arguably due others, or that he had an extra-marital affair, or that his disputes with writers and network executives were not always handled with perfect professional aplomb, only adds to the humanness of this humanist. So he was morally obtuse on occasion—I hold up Roddenberry and his literary corpus not as a moral beacon toward which we should strive, but for what we can learn from his creative visage of our future.

The contingencies that constructed the necessities of Roddenberry’s life show conclusively: no Gene Roddenberry, no Star Trek.

The contingencies of Roddenberry’s life unfolded within the necessities of his times, starting with the Second World War, in which Roddenberry served as a bomber pilot flying unprotected B-17 sorties in the South Pacific. After the war he found employment as a commercial pilot for Pan Am, and found himself involved in the single worst flight disaster in Pan Am’s history. Remarkably, Roddenberry survived the horrific crash, and as a consequence found himself flooded with thoughts on death, God, and the meaning of existence. Roddenberry’s two marriages, his ambitious but naïve start in television, his struggle to launch Star Trek and then keep it on the air after the second season, his battles with studios over the films and novels based on his series, and many more anecdotes, show that Star Trek could never have been so successful if it had not been produced by a man whose life experiences gave him an insight into human nature appreciated by the millions who tuned in to get more than just science fantasy. In short, the contingencies that constructed the necessities of Roddenberry’s life show conclusively: no Gene Roddenberry, no Star Trek.

Roddenberry was, first and foremost, a humanist, who used science to communicate his deeper intentions. Raised a Baptist, in his early teens he grew skeptical of certain theological claims, such as the Eucharist, or Holy Communion. “I was around fourteen and emerging as a personality,” he told David Alexander for an interview in The Humanist. “I had never really paid much attention to the sermon before. I listened to the sermon, and I remember complete astonishment because what they were talking about were things that were just crazy. It was Communion time, where you eat this wafer and are supposed to be eating the body of Christ and drinking his blood. My first impression was, ‘This is a bunch of cannibals they’ve put me down among.’” The skeptical scales fell from his eyes. God became “the guy who knows you masturbate,” Jesus was no different from Santa Claus, and religion was “nonsense,” “magic,” and “superstition.” For Roddenberry, science holds the key to the future, and as such he strove for accuracy. In the following letter, for example, Roddenberry responds to the legendary science writer Isaac Asimov, who had taken him to task for a scientifically inaccurate statement in one of the early episodes. We see Roddenberry properly respectful of this literary giant, yet appropriately defensive of his fictional child:

In the specific comment you made about Star Trek, the mysterious cloud being “one-half light-year outside the Galaxy,” I agree certainly that this was stated badly, but on the other hand, it got past a Rand Corporation physicist who is hired by us to review all of our stories and scripts, and further, got past Kellum deForest Research who is also hired to do the same job.

And, needless to say, it got past me.

We do spend several hundred dollars a week to guarantee scientific accuracy. And several hundred more dollars a week to guarantee other forms of accuracy, logical progressions, etc. Before going into production we made up a “Writer’s Guide” covering many of these things and we send out new pages, amendments, lists of terminology, excerpts of science articles, etc., to our writers continually. And to our directors. And specific science information to our actors depending on the job they portray. For example, we are presently accumulating a file on space medicine for De Forest Kelley who plays the ship’s surgeon aboard the USS Enterprise. William Shatner, playing Captain James Kirk, and Leonard Nimoy, playing Mr. Spock, spend much of their free time reading articles, clippings, SF stories, and other material we send them.

Despite all of this we do make mistakes and will probably continue to make them. The reason—Thursday has an annoying way of coming up once a week, and five working days an episode is a crushing burden, an impossible one. The wonder of it is not that we make mistakes, but that we are able to turn out once a week science fiction which is (if we are to believe SF writers and fans who are writing us in increasing numbers) the first true SF series ever made on television.

(Nevertheless, scientific errors crept into the show such that today books and web sites have been devoted to Star Trek bloopers.)

Roddenberry was a humanist in the purist sense of the word—he had a deep love of humanity and held out the greatest hope for our future, without depending on a higher power to achieve happiness.

Later, after Roddenberry’s fame skyrocketed along with the series (now in syndication with multiple spin-off series and feature films, generating hundreds of millions of dollars), the Star Trek creator was asked to comment on any number of deep issues, especially those of a religious and spiritual nature. Roddenberry was a humanist in the purist sense of the word—he had a deep love of humanity and held out the greatest hope for our future, without depending on a higher power to achieve happiness. He offered these thoughts on God and UFOs to Terrance Sweeney, for a book entitled God &, published in 1985:

I presume you want an introspective look at this. I think I’ve gone through quite an ordinary series of steps in life. I began as most children began, with God and Santa Claus and the tooth fairy and the Easter Bunny all being about the same thing. Then I went through the things that I think sensitive people go through, wrestling with the thoughts of Jesus—did he shit? Did he screw? I began to dare to believe that God wasn’t some white beard. I began to look upon the miseries of the human race and to think God was not as simple as my mother said. As nearly as I can concentrate on the question today, I believe I am God; certainly you are, I think we intelligent beings on this planet are all a piece of God, are becoming God. In some sort of cyclical non-time thing we have to become God, so that we can end up creating ourselves, so that we can be in the first place.

I’m one of those people who insists on hard facts. I won’t believe in a flying saucer until one lands out here or someone gives me photographs. But I am almost as sure about this as if I did have facts, although the only test I have is my own consciousness.

Roddenberry’s philosophical humanism was tempered with a practical realism necessary in dealing with television studios. MGM and CBS, for example, initially turned Star Trek down. NBC bought the show but had to pay for another pilot because the first one—“The Cage”—was “too cerebral.” They were also worried about Spock’s pointed ears, air-brushed out of the publicity stills to appease conservative network executives and potential advertisers. Thus was created a second pilot (another first in television history)—“Where No Man Has Gone Before”—which became a series classic. Finally, the first Star Trek episode aired on the night of my 12th birthday, Thursday, September 8, 1966. The program was “The Man Trap,” ironically the 6th episode filmed and not nearly the same quality as the two pilots. “The Cage” was later made into a two-part episode (the only one of the original series) and included black-and-white footage and some of the original actors who never appeared on the regular series.

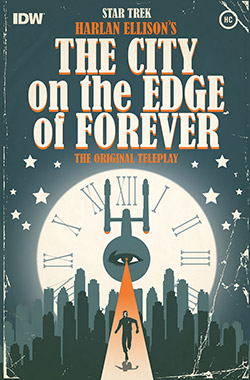

Script poster

One of the best known and arguably the finest program of the 79 episodes in the original series—“The City on the Edge of Forever”—was written by the highly-acclaimed science fiction writer Harlan Ellison. In 1994, Entertainment Weekly ranked all 79 episodes of the original Star Trek series—“The City on the Edge of Forever” was number one. The next year, TV Guide published their “100 Most Memorable moments in TV History,” for which “The City on the Edge of Forever” ranked number 68. The televised show won a Hugo Award, and Ellison’s original script—similar in its core but considerably different in details from what aired on television—won the Writers Guild of America Award for the Most Outstanding Teleplay for 1967–68. For $200 you can even purchase a pewter and porcelain desktop sculptured model of the famed time portal from the episode, produced by The Franklin Mint.

The history of “The City on the Edge of Forever” has become a point of gossipy controversy in Trek lore, so it bears brief synopsis. Most Star Trek histories and memoirs touch on the controversy, and most get the story wrong. To set the record straight, Harlan Ellison published an entire book on the subject in 1996, entitled (so you don’t miss it) Harlan Ellison’s The City on the Edge of Forever: The Original Teleplay that Became the Classic Star Trek Episode. The book is backed by copious documentation in support of his version of this tiny slice of television minutia, along with an unstoppable logorrhea made tolerable by Ellison’s inimitable style. To wit, on Roddenberry’s tendency to take credit for other people’s work, Ellison writes:

The supreme, overwhelming egocentricity of Gene Roddenberry, that could not permit him to admit anyone else in his mad-god universe was capable of grandeur, of expertise, of rectitude. And his hordes of Trekkie believers, and his pig-snout associates who knew whence that river of gold flowed…they protected and buttressed him. For Thirty years.

If you read all of this book, I have the faint and joyless hope that at last, after all this time, you will understand why I could not love that aired version, why I treasure the Writers Guild award for the original version as that year’s best episodic-dramatic teleplay, why I despise the mendacious fuckers who have twisted the story and retold it to the glory of someone who didn’t deserve it, at the expense of a writer who worked his ass off to create something original, and why it was necessary—after thirty years—to expend almost 30,000 words in self-serving justification of being the only person on the face of the Earth who won’t let Gene Roddenberry rest in peace.

To quote Captain Kirk from Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan: “Don’t mince words…what do you really think?”

Ellison submitted an initial treatment of the episode on March 21, 1966, and a revised treatment on May 13, 1966. The original script, touching on issues in the forefront in the 1960s, involved an Enterprise crew member dealing “infamous and illegal Jillkan dream-narcotics, the Jewels of Sound,” used (and abused) to handle the stress and boredom of long-term space flight. In addition, Ellison had a legless World War I veteran assist Kirk and Spock in their historical mission. Finally, Ellison developed the character of Captain Kirk as more morally complex than he had been in early episodes, in this case freezing at the crucial moment that demanded action. Roddenberry rejected these elements, apparently believing that drugs, cripples, and moral obtuseness were not good images for noble crews and heroic captains. To be fair, when Ellison penned his treatment there were only two scripts from which to work—“The Cage” and “Where No Man Has Gone Before”—and the show was undergoing rapid and dramatic changes in its early stages. Therefore, says Alexander, Roddenberry rewrote it himself after other staff writers failed to bring it up to the show’s standards.

Ellison disputes Alexander’s take on the matter, presenting a complex story that involves a number of writers exerting their influence—least of all Roddenberry. “I rewrote the script, I rewrote it again, I worked on it at home and on a packing crate in Bill Theiss’s wardrobe room in Building ‘E’ and when Gene kept insisting on more and more changes, and when I saw the script being dumbed up, I couldn’t take much more.” The script was redacted by Steve Carabatsos, Gene Coon, and Dorothy C. Fontana, and “fiddled” (says Ellison) by Roddenberry. In the end, Ellison was sufficiently displeased with the final product and requested that his name be substituted with his Writer’s Guild Association registered pseudonym, Cordwainer Bird, “which everyone in the industry knew was Ellison standing behind this crippled thing saying it ain’t my work and sort of giving the Bird to those who had mucked up the words,” Harlan explained in the third person, then confessing “but Gene called me and made it clear he’d blackball me in the industry if I tried to humiliate him like that; and I went for the okeydoke. I let my name stay on it.” To this day Ellison’s name stands on this most famous of Star Trek episodes, which originally aired on NBC on April 6, 1967.

I have now read “The City on the Edge of Forever” in all of its editions. Although I must admit that Harlan’s original script is richer, more complex, and more morally compelling than what aired on television, childhood memories create powerful preferences. To a twelve-year old boy, William Shatner cuts an heroic jib while Joan Collins fulfills youthful fantasies. Regardless, the story is not just another science fiction tale. Three decades later that episode came to represent to me a deeper theme of historical change. Since historians cannot go back in time to alter a jot or tittle here and there and observe the subsequently changed outcome, such historical fantasizing must be left to those who dwell in fiction. While science has yet to devise a way to travel backward in time, science fiction has no trouble at all (usually by encountering an “anomaly” in the space-time continuum), and the theme of removing an individual from the historical picture to trigger a different result has become one of the mainstays of the genre.

The discussion of fictional stories in this context may be defended as contributing to our scientific understanding of the nature of causality in history and biography. There is a role for thought experiments in all sciences—to broaden our perspective and deepen our understanding of a subject through the consideration of novel possibilities. The Austrian physicist and philosopher of science Ernst Mach considered thought experiments a form of empiricism because they derive from past experiences creatively rearranged. He notes that physicists’ thought experiments such as rolling balls down frictionless planes serve a useful purpose in establishing principles that can be tested experimentally in other ways. Einstein is the best-known example of a scientist many of whose most significant ideas were worked out in thought long before they were tested experimentally. He called these his “gedanken experiments.” But he was only doing what so many scientists do, and not just physicists. Economists are famous for their ceteris paribus assumption of “all other things being equal” thought experiments about the economy, conditions that rarely exist in the real world but serve a useful purpose for manipulating variables in theory that could not be rearranged in reality.

How do we conduct a historical thought experiment? Mach explains: “When experimenting in thought it is permissible to modify unimportant circumstances in order to bring out new features in a given case.” He also warns: “But it is not to be antecedently assumed that the universe is without influence on the phenomenon in question.” Mach’s admonition is well taken, and “The City on the Edge of Forever” presents a healthy balance between specific circumstances (contingencies) and universal effects (necessities), and how their interaction shapes altered histories. The story line offers a simple but powerful message about the actions of individuals and the contingencies of life, while recognizing that these occur within the context of influencing larger forces.

In “The City on the Edge of Forever” the theme of the present and future contingently linked to the past—where every individual and event has some relative effect (usually small, occasionally large)—is played out in this science fiction thought experiment. On Stardate 3134.0, an Enterprise landing crew is beamed down to a planet to rescue their temporarily psychotic physician, gone mad because of a cordrazine drug-induced accident (in Ellison’s original script drug abuse led to an on-board murder, for which the convicted crewman was condemned to spend the rest of his life on this barren planet). While on the planet, the landing crew investigates an anomalous source of energy causing “ripples” in the fabric of time. The crew comes upon an arch-shaped rock structure that Spock’s tricorder readings indicate is on the order of 10,000 centuries (one million years) old. Surging with power, it appears to be the single source of the time ripples. Kirk’s rhetorical inquiry of “What is it?” produces a response: “I am the guardian of forever. I am my own beginning, my own ending.” Spock, in his archetypical omniscience explains: “A time-portal Captain. A gateway to other times and dimensions.”

The crew of the USS Enterprise encounter the Guardian of Forever. Film still from the episode: “The City on the Edge of Forever,” first broadcast on April 6, 1967. (Credit: CBS)

Acknowledging Spock’s correct analysis, the “guardian” gives them a centuries-long glimpse into history, “A gateway to your own past, if you wish.” What they witness is every historian’s fantasy—a replay of history with the opportunity to go back and relive the past. “Strangely compelling, isn’t it?” Kirk queries. “To step through there and lose oneself in another world.” But as they ponder the imponderable, the still drug-crazed physician, Dr. McCoy, appears from behind a rock and leaps through the time-portal, which promptly terminates its historical replay. “Where is he?” Kirk asks. The guardian replies: “He has passed into…what was.” A landing party member who was in contact with the ship at the moment McCoy jumped through the time-portal suddenly loses all communications. “Your vessel, your beginning, all that you knew is gone,” explains the guardian. McCoy, in the manner of the increasingly popular “what if” genre of historical thought experiments, in something akin to the matricide problem of time travel, altered the past in a manner that erased the Enterprise from history. (Why the landing crew would remain is not explained, nor is the matricide paradox resolved, for if you go back in time and kill your mother before you were born, then you erase yourself from the continuum that allowed you to alter that original past. If McCoy changed the past in such a way that the Enterprise and her crew no longer existed, then he could not have jumped through the time portal to erase that history. )

Matricide paradox aside (which it must be for time travel scenarios to exist in science fiction), the solution is that Kirk and Spock must return to the past just before McCoy jumped through the portal and prevent him from doing whatever it was he did to alter the future. Exactly when they should jump through the portal and where on Earth McCoy landed is the problem. Spock, the science officer, offers a solution: “There could be some logic to the belief that time is fluid, like a river: currents, eddies, backwash,” Kirk concurs: “And the same currents that swept McCoy to a certain time and place might sweep us there too.”

Together they leap through the portal and arrive in New York City circa the 1930s and take refuge in the basement of a mission run by the angelic Edith Keeler (Joan Collins through soft-filter lenses, whose character Ellison patterned after “Sister” Aimee Semple McPherson, the first evangelist to employ the power of radio in the 1930s to reach the masses). Spock constructs a crude computer out of vacuum tubes in order to replay his recording of the guardian’s passage of time (which he was producing with his tricorder when McCoy jumped) to see if they can determine what McCoy did to alter the future. In the process, Spock gets a brief glimpse of the immediate future in a newspaper headline of that year that read Social Worker Killed, beneath which appears a picture of Edith Keeler. The image fades as a power surge burns out the tubes. Kirk arrives, after a plot-thickening encounter with Keeler in which the two appear to be falling in love.

Film still of Joan Collins as Edith Keeler (left) and William Shatner as Captain James T. Kirk (right), in the year 1930, in the episode “The City on the Edge of Forever.” (Credit: CBS)

“I may have found our focal point in time,” Spock explains to him. “Captain, you may find this a bit distressing.” A replay of the now-repaired computer, however, reveals a different newspaper caption six years into the future: F.D.R. Confers With Slum Area “Angel.” Above the headline is a photo of Edith Keeler. “We know her future. Within six years from now she’ll become very important, nationally famous,” Kirk enthuses. Spock gives him the alternative. “Or, Captain, Edith Keeler will die, this year. I saw her obituary. Some sort of a traffic accident.” Kirk is understandably confused. “You must be mistaken. They both can’t be true.”

Spock explains the paradox that such time travel thought experiments present. “Captain, Edith Keeler is the focal point in time we’ve been looking for, the point in time that both we and Dr. McCoy have been drawn to.” The now-enlightened Kirk says to no one in particular, “She has two possible futures, and depending on whether she lives or dies all of history will be changed. And McCoy…” Spock finishes the sentence: “…is the random element.” Kirk queries: “In his condition, does he kill her?” Spock answers with a double paradoxical problem: “Or, perhaps he prevents her from being killed. We don’t know which. Captain, suppose we discover that in order to set things straight again, Edith Keeler must die?”

Meanwhile, McCoy makes his appearance in New York, near Keeler’s mission, hung-over from his drug overdose. As he enters the mission to recover, he narrowly misses seeing Kirk and Spock as they descend to the basement where Spock has repaired his crude computer, to glance into the future one last time. “This is how history went after McCoy changed it,” Spock explains to Kirk. “Here, in the late 1930s, a growing pacifist movement whose influence delays the United States entry into the Second World War. While peace negotiations dragged on, Germany had time to complete its heavy-water experiments.”

In this altered version of history, Germany is the first to develop the atomic bomb. Mounted on V-2 rockets, these bombs allow Germany to defeat the allies and win the war, altering conditions so that centuries hence the Enterprise and her crew never existed. Since it was Edith Keeler who founded the peace movement, somehow McCoy came back and prevented her from dying in a street accident. (Of course, if he did she would have erased McCoy from the future, preventing him from returning to the past to save her life, in which case she would have been killed, allowing McCoy to live and save her life, and so on.) She lives, along with the cascading alternate contingencies of Nazi victory. Much to Kirk’s dismay, for history to be righted there is only one future Edith Keeler can have. Spock reinforces the overriding necessity: “Save her—do as your heart tells you to do—and millions will die who did not die before.”

The stage is set for the final scene. Kirk and Keeler are walking down the street hand in hand. She makes some mention of McCoy staying at the mission, which is the first signal to Kirk that he has arrived. Kirk exhorts Keeler to stay put while he bolts across the street toward the mission in front of which Spock is standing. As he reaches the sidewalk McCoy exits the building and the three reunite in mutual delight of recognition amid this temporal nightmare. A curious Keeler begins her journey into destiny by stepping off the curb and crossing the street, oblivious to a truck approaching at high speed. Kirk turns and sees the immediate danger in time to leap out and save Keeler. Spock insists Kirk stop himself. He does, but McCoy, unaware of the impending consequences, starts toward the street to save the doomed social worker. Kirk grabs him, preventing his intervention. Keeler is killed. In shock, McCoy exclaims: “You deliberately stopped me Jim. I could have saved her. Do you know what you just did?” Heartbroken and speechless, Kirk allows Spock the final line. ”He knows doctor. He knows.”

History was repaired, contingencies righted, necessities in place. Kirk and Spock suddenly appear out of the portal to the surprised landing crew who experienced almost no lapse of time. The Enterprise awaits their safe return, and the guardian concludes: “Time has resumed its shape. All is as it was before.”

In Ellison’s original script, the World War I crippled veteran named Trooper leads Kirk and Spock to a different character named Beckwith (not in the final televised version) who is the random element in the timeline who showed up to save Keeler. Kirk moves to stop him, but then hesitates. “He cannot sacrifice her, even for the safety of the universe,” Ellison writes. “But at that moment Spock, who has been out of sight, but nearby, fearing just such an eventuality, steps forward and freezes Beckwith in mid-step. Edith keeps going and we QUICK CUT to Kirk as we HEAR the SOUND of a TRUCK SCREECHING TO A HALT. As Kirk’s face crumbles, we know what has happened. Destiny has resumed its normal course, the past has been set straight.”

In an insightful epilogue that would have elevated the televised episode into literary enlightenment, Ellison allows the heroes to reflect on what has just unfolded. “We look at our race, this parade of men and women, and the unbelievable harm and cruelty they do,” Kirk opines. “And we sigh, and we say, ‘Perhaps our time is past, let the sharks or the cockroaches take over.’ And then, without knowing why, without even thinking of it, the worst among us does the great thing, the noble deed, that spark of impossible human godliness.” Spock continues the thought. “Evil can come from Good, and Good from Evil. But the little man…Trooper…” Kirk: “He was negligible. He fought at Verdun, and he was negligible. And she…” Spock finishes the sentence: “No, she was not negligible.” “But…I loved her…” Kirk anguishes. “No woman was ever loved as much, Jim. Because no woman was ever offered the universe for love.”

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 3.1 (1994).

Buy the print edition

In his introductory remarks on “The City,” Harlan disparages the “heroification” of such characters as Roddenberry, citing the historian James W. Loewen (from Lies My Teacher Told Me): “Heroification…much like calcification…makes people over into heroes. The media turn flesh-and-blood individuals into pious, perfect creatures without conflicts, pain, credibility, or human interest.” Indeed, this is a serious problem when our goal is an accurate portrayal of the way things really are. But when the goal is to envision a future of the way things could be, heroification is a virtue. We need heroes. We want heroes.

On January 30, 1993, NASA posthumously awarded Roddenberry the Distinguished Public Service Medal, with a citation that read: “For distinguished service to the Nation and the human race in presenting the exploration of space as an exciting frontier and a hope for the future.” Through Star Trek, Gene Roddenberry, Harlan Ellison, and others have offered optimism through a heroification of humanity and history. May we all find our own hero on the edge of forever. ![]()

Michael Shermer is the publisher of Skeptic magazine, a monthly columnist for Scientific American, and a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University. His book The Moral Arc is now out in paperback. Follow him on Twitter @michaelshermer.

This article was published on September 7, 2016.

I’m constantly surprised at the number of Star Trek fans I meet who are ardent right-wing Christians. I’ve had them deny that Roddenberry was a humanist and insist that he was a “good” Christian. When I have presented them with the evidence from the historical record, especially Roddenberry’s own words, they get angry and refuse to talk to me any further. Roddenberry started a great myth story with Star Trek. Like any myth tale, it has evolved over time with different people interpreting the stories through their personal perspective. Often, we see how the appreciation and practice of a mythical belief are far different from its historical origins. Still, it has only been 50 years and we have Star Trek fans (diehard fans who attend conventions) who have ignored the Progressive humanistic message of The Great Bird of the Galaxy and somehow interjected their Conservative Christian religious and political worldview into the myth. So enjoy celebrating the 50th Anniversary of this great Enterprise and Boldly Go!

Anger loses debates and friends

Old Dr. Sidethink quote

” arguing with funny mentalists is like playing bridge with monkeys,,,They think they’ve won if they eat the cards”

“In some sort of cyclical non-time thing we have to become God, so that we can end up creating ourselves, so that we can be in the first place.”

Huh?

” Bob Pease says:

September 7, 2016 at 8:58 am

“Trek-o-logy”

Hyphens ?

Hyphens ??

We don’t got to show you no steenkin’ Hyphens!!

GG

rjp”

You’re dead, Bob. Go away.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bob_Pease

Bob A. Pease is Dim, Jed

I am Robert J. Pease of Dr. Sidethink and Pope Bobby notoriety

Actually the TV premiere of Star Trek was on 6 September 1966 already – on a Canadian channel that could air it two days ahead of NBC in the U.S. This fact is moderately well known amongst serious students of Trek-o-logy and mentioned on most relevant websites about the early history of Trek. It is both funny and sad that the “it started on 8 September” myth is still all over the place 50 years later when it is so easy to disprove. Lesson: be skeptical even when it comes to popular anniversaries – sometimes they aren’t what they seem …

“Trek-o-logy”

Hyphens ?

Hyphens ??

We don’t got to show you no steenkin’ Hyphens!!

GG

rjp

Space Opera is satisfying need for fantasy involving heroes.

In the ’40’s we had Radio Serials ( cereals) .

Anyone analyzing Star Trek is missing the point that

Suspension of Disbelief is an essential element of Drama

Just one example ..

Why did Scotty speak English with a 20’th century accent.

Ir reality they would not have spoken anything resembling English

Rjp