Read the lecture transcript, listen to audio recording, or watch the video below:

I am in a very peculiar business. I appear on stages around the world as a conjurer. Now the American term for it is magician. It’s not a good expression because if you look in the dictionary the strict definition of a magician is one who uses magic. And magic, at least by the definition I prefer from a leading dictionary, is the attempt to control nature by means of spells and incantations. Now, ladies and gentlemen, in my time, as you might have guessed, I have tried spells and incantations. No good. You can spell and incant all you want; the lady will still be on the couch, waiting patiently to float into the air or will be imprisoned in the box with the saw blade descending upon her unprotected midriff, and in some danger of being severely scratched, if not worse! Spells and incantations don’t work. You have to use skulduggery. And let me make it very clear what the magical trade—the conjuring trade—is with a precise definition: it is the approximation of the effect of a true magician using means of subterfuge and trickery.

The magician, in the American usage, is an actor playing the part of a wizard. We are entertainers. I don’t think that there are many folks—but there are some out there by David Copperfield’s own admission to me—who still believe that they really can do the things they purport to do. After a magical performance we’ve all undergone the same experience, all of us in the trade; you get people coming to you afterwards and saying: “I really enjoyed what you did; thank you so much for coming.” And you say, “Well, it’s great to be here. I’m happy that you were pleased with it.” Then they say, “You know, the business with the bottles that multiplied. Obviously, that’s a trick. And the one where you did the thing with the rings and the ropes. That’s a trick too. But the one where you told the lady what word she’d chosen out of the newspaper—that, of course, can’t be a trick.” I’d say, “Yes, that’s a trick, too, but it’s disguised as a miracle of a semi-religious nature.” And they wink at you and they say, “Sure.” Then they walk away and tell their friends afterwards, “Well, he won’t admit it, but we all know.”

There is a hunger, a very strong hunger, within us all to believe there is something more than what the laws of nature permit. I’m not just saying audiences that watch the magician. I mean within us all. We’d like to have a certain amount of fantasy in our lives, but it’s a very dangerous sort of temptation to immediately assume that it must be supernatural or occult or paranormal if we don’t have an explanation for it. I can tell you that in my life I’ve spent a great deal of time investigating and observing and carefully noting and making use of psychology. I am not a psychologist; I have no academic credentials whatsoever, so I come to you today absolutely unencumbered by any responsibilities of that nature. There is no dean who will call me on the carpet tomorrow morning and say, “You shouldn’t have said that.” You see, I’m in the business of giving opinions from an uninformed point of view, except from the point of view of a skeptical person who knows how people’s minds work and often don’t work.

It was mentioned in the introduction to this talk that at the current rate of scientific growth, in a certain number of years scientists will consist of every human being on earth, as well as all the animals—the donkeys, the burros, the whole thing. Well, my friend David Alexander remarked to me, in a cruel aside, that even today certain parts of certain horses have become scientists. And that is quite true; I have met many of them and though they have Ph.D.s, you’d hardly know it. I’ve just come back from a project that’s ongoing at the moment and I’ve seen that principle at work. I must share with you another thing in passing. I have a theory; this is only a theory, and it is at present unproven. But observations so far tend to support its possible validity, with my advance apologies to Ph.D.s in the room. I have a theory about Ph.D.s and the granting of the degree itself. I am outside the field, not an academic, so as a curious observer I have many times seen films of, and in a couple of cases actually attended ceremonies where Ph.D.s are created. They are created, you know. The Ph.D. itself is earned, of course, but then the person who has passed all the tests and done all the right things in the right way and has been approved doesn’t become a Ph.D. until one significant moment where a roll of paper, usually with a red or a blue ribbon around it, is pressed into his or her hand. At that moment that person becomes a very special class of being known as Ph.D.

There is a hunger, a very strong hunger, within us all to believe there is something more than what the laws of nature permit. I’m not just saying audiences that watch the magician. I mean within us all.

Now, I have noted at those ceremonies, and perhaps you have observed it as well that the man who gives out those rolls of paper wears gloves. Why? Why would he want to wear gloves? Is the paper dirty? I don’t think so. Is there something about that roll of paper, or perhaps the ribbon, that he doesn’t want to contaminate him, and he doesn’t want to touch his skin? I’m going to postulate—just an idea—that perhaps there is a secret chemical that has been genetically engineered which is on the surface of that paper so that when the Ph.D. candidate receives that roll of paper this chemical is absorbed by the skin, goes into the bloodstream and is conducted directly to the brain. This is a very carefully engineered chemical which goes directly—please don’t laugh; this is science—goes directly to the speech center of the brain and paralyzes the brain in such a way that two sentences from then on, in any given language, are no longer possible to be pronounced by that person. Those two sentences are, “I don’t know” and “I was wrong”.

I honestly don’t know about that; however, my observations of the situation are that I have never heard any Ph.D. utter either one of those sentences. I have never heard them say, “I’d like to marry a lobster” either, but that doesn’t mean they can’t say it. But those two sentences never seem to pass their lips.

I am being exceedingly facetious, of course. I have every respect not only for science, but for those who pursue the various disciplines of science. It takes a great deal of courage, application, study, sacrifice (and in many cases, some outrageous attacks on your integrity and your ability) in order to maintain a point of view in science which may or may not be popular. I have been with many prominent scientists who have, from time to time, had to stick their professional necks out, and sometimes their necks get pretty badly beaten up in the process. It’s not an easy thing to speak against what is generally accepted.

What then is generally accepted? I’m afraid, due to the media impact on our civilization, that a great number of things are easily swallowed because they are repeated so often. They are endlessly presented to the public, and eventually make their way to the academic community as well. Any number of times I have spoken to scientists who, when I ask them a critical question about some belief in some sort of parapsychological, supernatural or occult claim, has said, “You know, I hear a good deal about it and Professor so-and-so did make a statement about it. Perhaps, Professor so-and-so, based upon the small amount of data which he has presently gathered, compared to what should be gathered, in order to establish a satisfactory statistical picture, an amount of data on which conclusions could be drawn by one of the various statistical pictures available to him, has come upon conclusions which are prematurely expressed. Therefore, furthermore, and moreover, on further examination….” That’s the academic’s reply. When they ask me, I simply say, “In my layman’s non-academic opinion, I think that Professor so-and-so is not rowing with both oars in the water.” It’s simple, direct, and an honest expression of my opinion.

I am presently faced with a situation, again unnamed, where I am going to have to show a number of dedicated, honest, hard-working people that they have made a colossal error of judgment. I have to do this in a resounding manner, simply because to not do so could result in a great deal of personal damage, grief, and considerable heartbreak and discomfort to a great number of people who are already laboring under certain disadvantages and burdens that they did not bring upon themselves. I hate to be so mysterious about it, but it is an ongoing work of investigation. I am not often involved in that serious a situation. Usually my circumstances are more open—I am looking into an astrologer’s claims or into some sort of pseudoscientific thing. But I always have to remember an experience that occurred to me.

It is easy, when faced with an apparently supernatural phenomena, to say “I guess it’s a ghost” or “It must be paranormal,” or “It could be poltergeists,” and we walk away from it because we can’t or won’t, look a little further into it. Some years ago, when I lived in New Jersey my house was a sort of a wayside stop for itinerant magicians, conjurers, mountebanks—various characters of ill repute who would come by to visit for awhile. One time I came home after a couple of days away, very tired, and came in on my foster son, Alexis, who was in the kitchen helping a couple of magicians drink up the beer. I walked in and said, “Guys, I’m very, very tired; I’m going to bed. I’ll see you in the morning.”

I guess they carried on until late that night. I fell asleep, woke up the next morning, came staggering into the kitchen in time to see them eating up more of my groceries in the form of breakfast at this time. I sat down, got a half cup of coffee into me and straightened up the table. Alexis looked at me and said, “What’s with you?” I said, “I think last night I might have actually had a classic example of the O.B.E.” That’s the out-of-body experience. It means that somehow you find yourself out of your body and looking down on it or from a distance. Alexis looked at me and said, “Sure. You?” I said, “Yes, I have to be honest. It appears to me as if I did undergo such an experience.”

“OK, give us a description,” they replied. The two magicians at the table leaned closer over their bacon and eggs and wanted to hear what I had to say. “Well, I remember waking up in the middle of the night—I couldn’t get to sleep at first because I was so tired, so I turned on the television. The program went on and on and I eventually fell asleep. I remember waking up in the middle of the night, and I felt that I was spread-eagled against the ceiling of my bedroom, looking down at the bed. Alice, my black cat, was curled up in a ball in the exact center of the bed so that I had to be way over to one side. And I was, of course, trying not to disturb the cat! As I was up against the ceiling I noticed that the room was lit in sort of a grayish light. I looked down toward the television set and saw nothing but static on the screen and heard nothing but white noise. What I saw was startling. I saw myself, in bed, scrunched over to one side, a chartreuse bedspread on it, with Alice the cat in the middle. I noted that as she opened her eyes they were green. It almost looked like two holes punched through her head. She looked at me and went, ‘hmmph’ and went right back to sleep.”

Now that was a very strong experience for me. I really believed, from the evidence presented to me, that I had an out-of-body experience that matches the description that we’ve all heard about so many times. But, fortunately for me, I’m not really dead-set against having my belief structure disturbed or having new facts come in that would disturb my previous convictions. And, fortunately, I am able to tell you what actually happened. Alexis looked at me and said, “I’ve got two things to show you.” He went to the foot of the stairs and came up with a big, transparent laundry bag. He had taken it half way down to the laundry room. He brought it all the way up the stairs, and inside noted sheets, pillowcases, and the chartreuse bedspread. He said, “That’s been there since yesterday.” The bedspread hadn’t been on the bed last night! I dashed to the bedroom door, looked in, and the spread I used when the other one was in the laundry lay on the bed. They looked nothing alike. Alexis then called my attention to the patio, noting that he had put Alice outside yesterday afternoon because one of the magician guests was highly allergic to cats. She had remained outside, very unhappily, through the night and into this morning. She could not have been curled up in the middle of the bed last night.

It was a dream—a hallucination, if you will. I had two very good pieces of evidence that it could not have happened. That’s important in that if I did not have one or both of those pieces of evidence, I would now have to say to you that, to the best of my knowledge, I had an out-of-body experience. But, all the other out-of-body experiences we hear of, we have to wonder. Those folks are not quite as skeptical about the subject as I am, in most cases. If they don’t have some convincing evidence to the contrary, what’s to stop them from saying, “I’m absolutely certain I’ve had an out-of-body experience?” There is no other explanation for it except the possible and rather parsimonious conclusion that they were either dreaming or had a hallucination. It might have been a bad pork chop, for all we know. Please consider that carefully, and don’t forget it, because it’s a good example of how even the arch-skeptic could possibly have been taken in.

I have had a number of small experiences like that, including the déjà vu type experiences that so many people have had. (I love the line from the fellow who says, “I keep having the same déjà vu, over and over again.”) But I have resisted the temptation to merely say, “Well, at last I’ve got proof of it.” I’m highly skeptical, but what is that skepticism based on? If you’re skeptical as well, have you asked yourself, “Upon what do I base my skepticism?” Are you just plain ornery? Do you just not want to go along with the status quo? Do you know some people who believe in it who are really pretty dense and you don’t want to join their group?

You must have a reason, I think, for yourself and for others as to why you are skeptical. These things are not likely to be true; therefore, you need proof of them. We’re not required to prove a negative; we can’t do that. I can’t prove telepathy doesn’t exist. I remember getting a question years ago. A lady stood up in the audience and said, “Can you prove to me that ESP doesn’t exist?” I said, “No, I can’t.” She sat down with her arms folded and replied “Ah ha.” That was a victory for her. I went on to explain that I can’t prove a negative. My question is, “Do you believe in it?” She said, “Absolutely.” I asked if she could prove that it is so. She said, “Well, I’m quite convinced of it.”

“That’s not my question,” I responded. “Can you prove that it is so? You’re the one making the claim.” We skeptics, as Michael Shermer clearly pointed out, are not in the business of debunking. If I were in the business of debunking, and I’ve often had that label pinned on me and I’ve always resented it and denied it—it means I would go into an investigation convinced that “this ain’t so and I’m going to show you that it isn’t.” I’m not a lawyer; I don’t have an advocacy position to take. I go into a situation as an investigator. To be perfectly fair, I can’t prove a negative, but I go into this thing prepared to be shown. Am I prejudiced against it? Oh, yes! I have to admit that. But if you’ve been sitting by a chimney for 63 years on the evening of December 24 and a fat man in a red suit has never bounced down that chimney, you can say, “One hundred percent of my evidence shows me that this claim is not necessarily so. I cannot prove that it isn’t, but it’s not very likely to be true, based on what we know.”

The Santa Claus example may seem trivial and a little inappropriate, but it is actually a good metaphor for so many paranormal and pseudoscientific claims. Another is flying reindeer. This one we can actually test. (Please don’t tell the SPCA about this.) I don’t really want to do the experiment, but let’s walk through it as if I were doing it. It’s a thought experiment. Let’s select, by some randomizing process, a thousand reindeer. We’ll number them and get them all together in a reindeer truck (I don’t know what you put reindeer in) and take them to the top of the World Trade Center in New York. We are going to test whether or not reindeer can fly. You have your reindeer all lined up, a video-camera operator standing by, lots of pads of paper and pens at work. The time is now ten past ten in the morning. OK, first experiment. Number one reindeer, please, up to the edge. Camera going? Good. Push. Uhh, write down “no”. Really NO! Number two. Push. I don’t know what the result of the experiment will be; I suspect strongly what it will be, based upon my meagre knowledge of the aerodynamics of the average reindeer, though I’m not an expert on it. But based upon previous accounts of what reindeer can and cannot do, I think we are going to end up with a pile of very unhappy and broken reindeer at the foot of the World Trade Center. And probably a couple of policemen will be standing by a squad car saying, “I don’t know, but here comes another one.”

What have we proven with this experiment? Have we proven that reindeer cannot fly? No, of course not. We have only shown that on this occasion, under these conditions of atmospheric pressure, temperature, radiation, at this position geographically, at this season, that these 1000 reindeer either could not or chose not to fly. (If the second is the case, then we certainly know something of the intelligence of the average reindeer.) However, we have not, and can not, prove the negative that reindeer cannot fly, technically, rationally, and philosophically speaking. People will often look at this example and say, “Well, how many reindeer would you have to test?” I’m not going to get into the statistics of the argument; I will only tell you that you cannot prove a negative. The other folks who claim that something is so are required to prove it. It is what we call the burden of proof. In this case, if it’s so it’s very easy to prove. Just show me one flying reindeer. Then they rationalize, saying, “Oh, no. It’s only the eight tiny reindeer that live at the North Pole who can, and will, on the evening of December 24, fly to do that specific job.” In that case you have to throw up your hands and say, “Well, I don’t think your hypothesis is very testable.” Don’t spin your wheels!

Thought experiments like this one only go so far. As an example of a real experiment testing unusual claims, I just came back from Hungary where I was invited to Budapest by the Academy of Sciences. They are very concerned about the fact that now that many of these countries are freed from the burdensome and onerous yoke of Communism and have the freedom to receive all kinds of scientific information in the form of journals and lectures, nonsense comes in as well. The astrologers, the faith healers, the ESP artists, the people with the pendulums, the water dowsers—they’re lined up and pouring across the border because they see a new market. The scientists of Hungary were concerned about this. A well-known member of parliament who is also a well-respected brain scientist of international repute, said to me, “Mr. Randi, have you seen any of the publicity on the magnetic ladies?” I had.

In case you’re not familiar with the magnetic ladies of Hungary, I will relieve you of that ignorance immediately. You may have seen a picture that made all the wire services in this country last year, of the magnetic man from (then) Leningrad. There was a picture of a middle-aged man standing like this, naked from the belt up, with a flatiron stuck here, a hammer there, nails, razor blades—all kinds of metal clinging to his body. The caption said that he attracted these things. They just jumped, willy nilly, onto his body. He was somehow magnetic. I’ll bet his wristwatch was a mess! Don’t bring him near your computers! I can just imagine him going through a steel door. Bam! Right into it!

Well, I took that with the proverbial grain of salt about the size of a basketball, and just put it in the scrapbook and forgot about it. But the professor asked me about the magnetic ladies of Hungary, and he said, “Their reputation is such that objects, not necessarily metallic ones, cling to their bodies with such tenacity that a strong man cannot tear them loose.” Now, wait a minute! Suppose you have some instant glue, and we take a tennis ball and stick it on the lady’s neck, on the side. If a strong man can’t tear it off, he’s going to tear her skin off—or her head! Something has to give! My scientist friend and sponsor of this trip looked at me and said, “How can they make claims like this?” I said, “Well, show me the magnetic ladies.” He said that the following day, after the press conference, they were scheduled to arrive. I could hardly wait.

One of the parapsychologists had suggested that he could bring me some instrumentation for detection of their magnetism. He promised that we’d take the two ladies down to the laboratory, (hand in hand, clinging to one another, no doubt). I declined to go to the laboratory because the laymen reading the report in the newspaper wouldn’t understand “laboratory”. What are you going to do? Put a cyclotron on her ear? No. I equipped myself with a scientific device and I went along. The device was called a compass. It’s a scientific instrument and an easy way to perform the test. If a woman is magnetic, the compass is going to point right at her. The two ladies showed up. I told my friend in advance that he must understand that the claim is one thing; the event itself will often be something totally different. It won’t be half as entertaining or amusing, or true, as the actual demonstration.

One lady literally did this: she took her wristwatch off her wrist and did this. [Randi put his watch on his forehead and it stays there without falling.] “How do you explain that?,” she said. I looked at both ladies, who were wearing very greasy, high gloss makeup. It was obviously sticky, mixed with a little perspiration. She said, “We have no explanation for it.” I said I didn’t find it terribly difficult to explain.

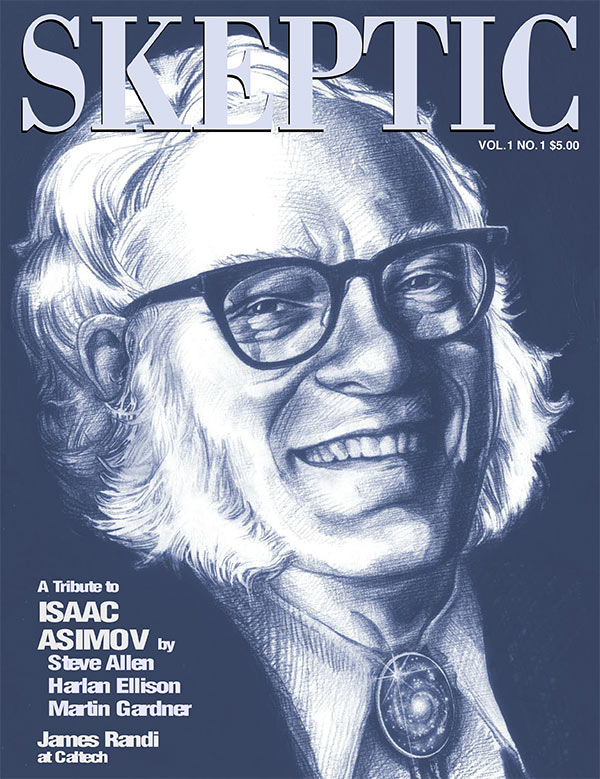

This lecture transcript appeared in Skeptic magazine 1.1 (1992)

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

The second lady had an even better demonstration. She took a small ceramic saucer from her purse, stuck it on her forehead, where it remained. “And how do you explain that?” she parroted the other woman. I pulled it off her forehead, and stuck it on the foreheads of the first four people standing on my right. It stuck very effectively to the foreheads of all of them! Then we tested under controlled conditions. (By the way, the compass test failed miserably; it pointed to North, obstinately refusing to point at them.) I asked for soap and water and, through the interpreter, asked the first lady if I could wash her forehead to remove the makeup and any perspiration that might be there. She informed me that if she washed her forehead it wouldn’t work because water is absorbed into the skin and water and electricity, or magnetism, don’t mix. She denied that that would be a satisfactory test, as did the second lady, and they left. “You’ve learned your first lesson in the scientific investigation of unusual claims,” I told the Professor. “Don’t start to give theories on how it might work until you’ve seen whether it meets the claims of the newspaper account, or is really something much less impressive.

To be fair to these women, I can see how that account might have ended up in a newspaper. I’m sure those ladies didn’t say to the newspaper reporters, “A strong man can’t pull it away from me.” But a reporter is a human being and maybe his story doesn’t look all that great when he writes that things cling to their bodies. Then perhaps he thinks: “Um, how about ‘with such tenacity that a strong man can’t pull them loose’”? Now, he has a story! What I’m saying is that the media are as much to blame for the spread of nonsense and pseudoscience as the claimants themselves. For example, a few years ago the New York Daily News, on page three where they put the “heavy news” and sensational stuff, announced that a student at Duke University had successfully in great detail described not only an aircraft accident 24 hours in advance of the event, he even gave the number of people who would be killed. He was short by only two. He even described the location of the crash in the Canary Islands. That was picked up by news services and was featured on television programs; it was on every newscast for quite some time. It was received by the press as a genuine example of prophecy, and the director of the program in which this was involved at Duke University actually made a statement that he had a sealed envelope 24 hours before in his safe that was not touched by this gentlemen until after the episode had taken place. It was allegedly torn open at that time and it contained the prediction.

To explain this phenomena I will take you into a different world, for just a moment, so you will understand something. Magicians know how this young man could very easily have done this trick. I won’t go into all the details; you can imagine some of them yourself. But the effect is exactly as described—a sealed signed envelope, put into a safe, later carefully opened. Inside you either find a tape cassette or a sealed letter with all kinds of security on it, signed, maybe genuinely notarized, as of the day before. It contains the prediction. A miracle of a semi-religious nature? No, it’s a trick. It can be done by any good magician.

Now, let us return to the article in the Daily News, first edition. It came out in the afternoon. It had the story on page 3, and a box in the middle of it describing the mechanics of how it had been locked up in a safe and it had a final paragraph which quoted the student at Duke University who made the prediction with this disclaimer: “It’s all part of the publicity for my magic show, which is happening tomorrow night. Don’t take it seriously.” The second and third editions of the Daily News had everything except that one sentence.

Another example of how the media distorts claims comes from a young fellow who lived a few doors down from me when I was living in Rumson, New Jersey. He was one of the local characters who did adventurous things like going out on rafts and sailboats. I thought he was a nice kid. One day on the front page of the New York Times there was a little box showing a map of the Bermuda Triangle with a Maltese Cross on it. The headline read: “Rumson boy lost at sea in Bermuda Triangle.” I read the short article, continued on another page, which said he had taken off in his one-man sailboat, sailed into the Triangle carrying a radio transmitter, and hadn’t been heard from since. The Coast Guard was searching for him. No sooner had I finished reading this and had called some friends in New York to tell them about it, I went out to pick up the mail and to my shock there was this kid waving hello to me. He was perfectly all right! I said to him, “You’re in the Times this morning.” He said, “Yeah, they picked me up late last night and they brought me in. They want me to be observed in the hospital, but I feel perfectly all right. We had a bit of a storm; I lost the radio overboard and they finally picked me up very, very early, around 2:30 this morning and they flew me in.”

Though the first story made a big splash, the followup never appeared in the New York Times or any other paper of which I know. It’s still part of the mythology about the Bermuda Triangle. So far as we know, from reading accounts that were published in newspapers, that kid is still someplace out in a sailboat in the Bermuda Triangle or perhaps taken off to Mars. You’ve got to learn that newspaper editors and reporters are subject to the same kinds of pressures that we all are. We all want something successful. Often the choice is between a story and a non-story. We have to realize that we cannot depend on the media to always to represent the facts as they actually are. That’s not a great deal of news to you, but you must bear it in mind at all times. Be careful about accepting what appears in print; don’t let them say to you, “They put it in the paper; it must be so,” or “Someone wrote a book on it. It must be so.”

Furthermore, books are often published which, before they actually reach the stands and are on sale, have been completely refuted because they are based on false information. Do they immediately withdraw them? No. I’ll give you a good example. There’s a book called Learning to Use Extrasensory Perception. Its published by Charles Tart, a respected psychologist at University of California, Davis. I heard Dr. Tart give a talk in Casper, Wyoming. I’m going to tell you exactly what he said and see if your reaction is the same as mine. I recorded it on tape so I know exactly the words he said; this is not a case of interpretation or faulty recollection. He said, in speaking to the audience:

There was a time, years ago, when I was highly skeptical of any paranormal claims of any kind. One of the things that convinced me that there must be something to this is a strange experience that I personally went through. It was wartime. I was at Berkeley, California, and everybody was working overtime. We worked until very late hours of the night and the young lady who was my assistant at the time worked with me until very late this one night. She finally went home; I went home. Then the very next day she came in, all excited. She reported this event. It was wartime; they did work overtime. They often were very, very tired when they went home. It was understandable they would fall into a deep sleep and get as much sleep as they possibly could during the night. She reported that during this night she had suddenly sat bolt upright in her bed, convinced that something terrible had happened. “I had a terrible sense of foreboding,” she said, but she did not know what had happened. “I immediately swung out of bed and went over to the window and looked outside to see if I could see anything that might have happened like an accident. I was just turning away from the window and suddenly the window shook violently. I couldn’t understand that. I went back to bed, woke up the next morning and listened to the radio.” A munitions ship at Port Chicago had exploded. It literally took Port Chicago off the map. It levelled the entire town and over 300 people were killed. Whether it was an accident or sabotage, no one ever found out. She said she had sensed the moment when all these people were snuffed out in this mighty explosion. How would she have suddenly become terrified, jumped out of bed, gone to the window, and then—from 35 miles away, the shock wave had reached Berkeley and shook the window?

Indeed, she remembered looking at the clock to see what time it was—right to the minute. Well, when I heard this, I said to myself, “There’s something wrong here.” I see a couple of smiles around the audience; maybe you’ve spotted the same thing I did. I had a geologist friend sitting three or four seats away; I handed him a note. He winked, smiled, got up and left the room. He came back in, handed it to me, and it just said on it, “8 seconds.” What question did I ask him? [Answer from audience: What is the difference in time of propagation over a distance of 35 miles of a shock wave through the air, compared to a shock wave through the ground? The difference is 8 seconds.] So 8 seconds before that window shook, she had been startled by the room itself shaking, not by the airwave, but by the groundwave. My theory is this: the groundwave which shook the bed startled her, she swung out of bed, went over to the window, looked outside, didn’t see anything, went to turn away from the window and suddenly the pane shook in front of her. The next morning I went to Professor Tart where he was having breakfast by himself. I had known him through correspondence and phone conversations but had never met him personally. I went over, introduced myself, sat down for a moment and gave him this bit of theory. I said there would be 8 seconds difference in the time. He didn’t look up from his scrambled eggs for the longest time. Finally, when he did, he smiled and said, “Mr. Randi, that may be the explanation that you prefer.” I think he had just decided that he wasn’t going to entertain that idea very solidly. But I don’t know that he ever made that statement subsequent to that, so maybe he did come to the conclusion that what I offered as an explanation was more likely to be true. But it is so typical of the field! Again, I’m involved in some stuff that I can’t tell you about, and I apologize for that, where I have a number of prominent scientists who are absolutely ignoring, refusing to look at very good evidence in this case that I’m investigating. They can come up with rationalizations for it that you wouldn’t believe, unless you’ve been through this process before. It is incredible how they can ignore good evidence to show that there is a prosaic, rational, and very probable explanation for what they are observing.

I want to close this presentation with some parallel examples of scientific claims that turned out to be so much nonsense. Let’s go back to 1903 in France. You may have heard of this, if not it really is something you should look up. A prominent scientist—a physicist named Rene Blondlot—startled the world of science with his announcement of the discovery of N-rays. A very well respected man who had won many prizes in science and justifiably so, he was doing experiments by today’s standards that were very simple—such as finding the speed of electricity in a conductor. It sounds easy today, but in those days it was a very sophisticated experiment and not all that easily done. Blondlot was in his 70s at the time when he discovered N-rays, named after the town of Nancy, where he was head of the Department of Physics at the University of Nancy.

What were N-rays? N-rays were allegedly radiation exhibiting impossible properties emitted by all substances with the exception of green wood (wood not dried out) and anesthetized metal. (Metal that had been dipped in ether or chloroform did not give out N-rays!) Within a matter of six to eight months of the announced discovery of N-rays, 30 papers had come in from all over Europe confirming the existence of N-rays. Reports were published in journals despite the fact that there were many laboratories reporting failure after failure in replicating the results. Such acceptance was understandable considering that X-rays, which also exhibited unsuspected properties, were by then firmly established.

What Blondlot had was a basic spectroscope with a prism (not glass, but aluminum) on the inside, and a thread. The narrow stream of N-rays was refracted through the prism and coming out produced a spectrum on a field. The N-rays were reported to be invisible, except when viewed when they hit a treated thread (for example, treated with calcium sulfide). They moved the thread across the gap where the N-rays came through and when it was illuminated that was reported as the detection of the N- rays.

Before long N-rays were established as factual. Nature magazine was skeptical of the N-rays since laboratories in England and Germany were unable to find them. (Germany had just discovered X-rays the decade before and the French were annoyed that they didn’t have a ray.) Nature sent an American physicist named Robert W. Wood from Johns Hopkins University to investigate. Now, I’ve been accused of skulduggery in my time, but what Wood did was brilliant. When no one was looking he removed the prism from the N-ray detection device and put it in his pocket. Without the prism the machine could not possibly work because it was dependent on the refraction of N-rays by the aluminium-treated prism. Yet, when the assistant conducted the next experiment he found N-rays! He swore they were there.

When the experiment was over Wood knew it was really over. He was prepared to make his report, and when he went to replace the prism back in the machine, one of the other assistants saw him do this and thought he was actually removing it, and he decided to show Wood up. Thinking Wood had removed the prism (when he had actually put it back), he set up the experiment, could find no lines, and opened the box to show that the prism was not there and to his dismay, there it was! The whole incident blew up. Papers were withdrawn, those that were in the mail were retracted, and N-rays disappeared from the scene.

How did this happen? How did over 30 papers get published? Not because the scientists who wrote the papers were stupid. Not because they were lying. But because they were deceiving themselves. Irving Klotz made this observation in Scientific American:

According to Blondlot and his disciples, then, it was the sensitivity of the observer rather than the validity of the phenomena that was called into question by criticisms such as Wood’s, a point of view that will not be unfamiliar to those who have followed more recent controversies concerning extrasensory perception. By 1905, when only French scientists remained in the N-ray camp, the argument began to acquire a somewhat chauvinistic aspect. Some proponents of N-rays maintained that only the Latin races possessed the sensitivities (intellectual as well as sensory) necessary to detect manifestations of the rays. It was alleged that Anglo-Saxon powers of perception were dulled by continual exposure to fog and Teutonic ones blunted by constant ingestion of beer.

Yet science does not always learn from these mistakes. Visiting Nancy recently and speaking on the subject of pseudoscience, I discussed this example and though I was in the city that gave the name to N-rays, no one in the audience had ever heard of them, or of Blondlot, not even the professors from the University of Nancy! Now let’s go to modern Germany, after the fall of Communism, and compare N-rays to the newly discovered “E-rays.” They are actually called Erdestrallen, or “Earth-rays,” but I’ve gotten the media all over the world to call them E-rays, a sort of parallel to N-rays. E-rays are even sillier than N-rays. What are they? First of all they cannot be detected by any known means, except by water dousers. They cause cancer. They supposedly come from the center of the Earth. The West German government spent over 400,000 marks, or about $200,000, to pay dowsers to go around to hospitals that were federally funded and federal office buildings to move beds and desks that were in the way of these deadly E-rays. I offered to go over for nothing and conduct a very simple two-part test: 1. Can one dowser find the same spot twice? and 2. Can two dowsers find the same spot once? I told them about this and their response was,”We don’t need to do the experiment because we know dowsing works. It’s been around since the Middle Ages and the historical tradition validates its truthfulness.”

I challenge all the dowsers in a similar way. Since 94 percent of the Earth’s surface has water within drillable distance my challenge is to find a dry spot! They don’t want to do it. Why? Because they only have a six percent chance of success. Dowsing is an idiomotor reaction that is very deceptive. It is an unconscious motion that you cannot detect and it looks for all the world like some mysterious force.

In a similar fashion, a few years ago I was in France investigating the results of experiments done by Jacques Benveniste on water with memory. He managed to get his article published in Nature, who put a disclaimer in the middle of the paper that perhaps “vigilant members of the scientific community with a flair for picking holes in other people’s work may be able to suggest further tests of the validity of the conclusions.” Nature sent a team of investigators over to his laboratory, of which I was a part. [The other two were John Maddox and Walter W. Stewart.] We showed that there were serious problems with the protocol, as well as the fudging of data. When controls were tightened, the experimenter could not replicate the results.

Then there is the theory of homeopathy born approximately 220 years ago, the brainchild of one Samuel Hahnemann. Medicine was in its infancy. Poor people could not afford doctors and recovered more often than the aristocracy who received all sorts of substances, which often killed them. Samuel Hahnemann gave sick, poor people water, which was suppose to contain a curative agent. Since these people did not go to doctors, they tended to survive, and this supported his belief in the curative power of his special water.

The first principle of homeopathy is that an extract of some substance in water will help cure you. The second principle is that an attenuated, or diluted solution will work even better. How diluted were these? If you take a solution and dilute it with 10 parts of water for every one part of itself, you’ve got what is called a “one solution.” If you take one part of that and put it in 10 parts of water, now one part in 100, it’s called a “two solution.” If you have a “five solution,” you have one part in 100,000. When you get to “Avogadro’s limit” there is a chance of there being one molecule in the solution. One more dilution and you have one chance in 10 of there being one molecule in the solution. Well, the homeopathy people start off with a solution of 10 to the power of 50 (a one followed by 50 zeros)! Since there are 10 to the power of 23 stars in the known universe, that’s what I call dilute. But that’s nothing. They go all the way to 10 to the power of 1500!!!

That is so diluted that I could not conceive of what 10 to the 1500 really means, so I called Martin Gardner and asked for an example with which to illustrate it. He called me back and said that an equivalent is to take one grain of rice, crush it up in a teaspoon and dissolve that powder in a sphere of water the size of the solar system, then repeat that process two billion times!! (The technical problems of mixing such a solution are obvious!)

The critical point of homeopathy—the point of all this diluting—is that every molecule of water that comes into contact with the homeopathy water retains the memory of that special water! Thus a little substance can go a long way. I have a simple question from a layman’s perspective. Since water has been around for “billions and billions of years,” in this process it must have come into contact with every organic and inorganic molecule on Earth. That being the case, why not just give the patient ordinary tap water?

James Randi appeared on the cover of Skeptic magazine 5.1 (1997)

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

In fact, these homeopathic waters are so diluted that the homeopathy doctors and scientists can’t even tell the difference between the water with iron and the water with gold. Come on folks, let’s get real. There is no evidence that this stuff works, yet people go right on believing anyway. Here’s a typical response, this from a letter written by Boaz Robinzon of the Faculty of Agriculture: “I want you to know that no matter what the Nature investigating committee has written, I am still confident that the phenomenon observed is a real and reproducible one and it is only a matter of time until we shall be proven right.”

That’s a classic example of someone who does not wish to face reality. I’ve been going around the world telling people to get real for years. That’s the peculiar business that I’m in. I shouldn’t have to be in that business but someone has to do it. Will it ever end? Probably not, but perhaps with the efforts of the skeptics and scientists we can “dilute” it a little! ![]()

Thank you.

About James Randi

James Randi is a retired professional magician, author, and lecturer. He is the founder of the James Randi Educational Foundation and was a founding fellow of CSICOP—the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal—now called The Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. Randi has taught at New York University (NYC) and at Brookdale Community College in New Jersey and has spoken for numerous schools, colleges, universities, and prominent organizations internationally.

The JREF offers a $1 million prize to anyone who can show, under proper observing conditions, evidence of any paranormal, supernatural, or occult power or event. To date, no one has claimed the prize.

This article was published on October 24, 2020.

The world needs more “amazing” Randi’s.

He will be missed.

I will miss Mr. Randi’s blunt, inventive, and often humorous exposés of various frauds.

Deans wear gloves at graduation ceremonies to emphasize the formality of the occasion – as does the Queen when granting knighthoods.

James Randi was a good man. He shall be missed.