During her sojourns among the Inuit throughout the 1960s and 70s, pioneering anthropologist Jean Briggs observed some peculiar parenting practices. In a chapter she contributed to The Anthropology of Peace and Nonviolence, a collection of essays from 1994, Briggs describes various methods the Inuit used to reduce the risk of physical conflict among community members. Foremost among them was the deliberate cultivation of modesty and equanimity, along with a penchant for reframing disputes or annoyances as jokes. “An immodest person or one who liked attention,” Briggs writes, “was thought silly or childish.” Meanwhile, a critical distinction held sway between seriousness and playfulness. “To be ‘serious’ had connotations of tension, anxiety, hostility, brooding,” she explains. “On the other hand, it was highest praise to say of someone: ‘He never takes anything seriously’.”1 The ideal then was to be happy, jocular, and even-tempered.

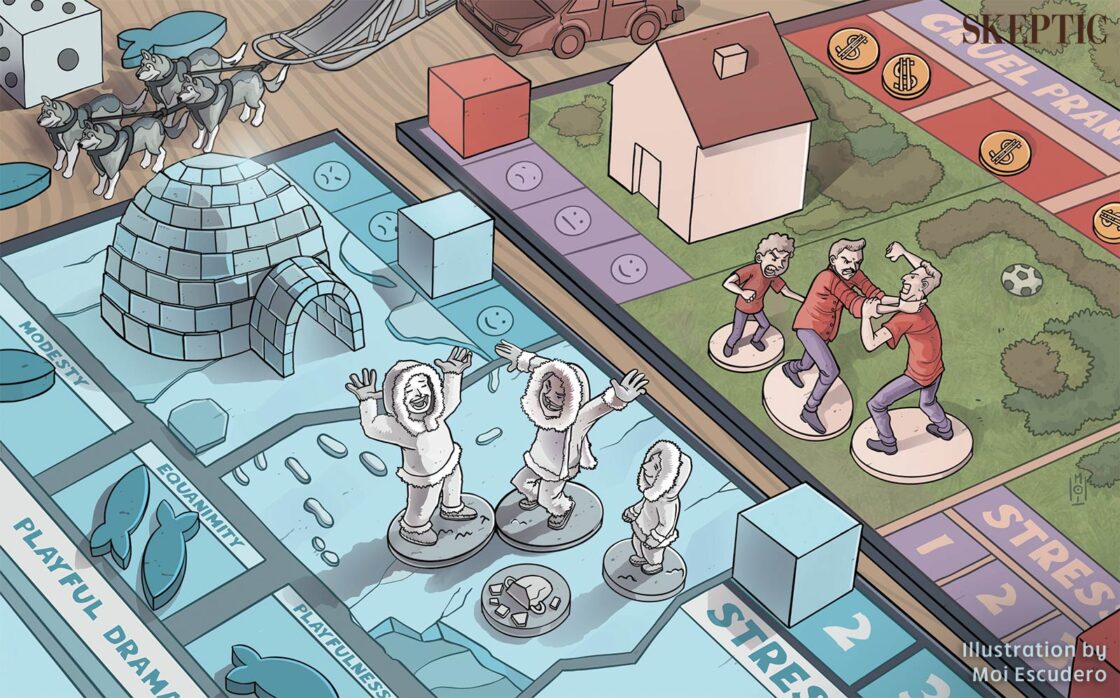

This distaste for displays of anger applied in the realm of parenting as well. No matter how unruly children’s behavior, adults would refrain from yelling at them. So, it came as a surprise to Briggs that Inuit adults would often purposely instigate conflicts among the children in their charge. One exchange Briggs witnessed involved an aunt taking her three-year-old niece’s hand and putting it in another child’s hair while telling her to pull it. When the girl refused, the aunt gave it a tug herself. The other child, naturally enough, turned around and hit the one she thought had pulled her hair. A fight ensued, eliciting laughter and cheers from the other adults, who intervened before anyone was hurt. None of the other adults who witnessed this incident seemed to think the aunt had done anything wrong.

On another occasion, Briggs witnessed a mother picking up a friend’s baby and saying to her own nursling, “Shall I nurse him instead of you?” The other mother played along, offering her breast to the first woman’s baby, saying, “Do you want to nurse from me? Shall I be your mother?”2 The nursling shrieked in protest, and both mothers burst into laughter. Briggs witnessed countless more of what she calls “playful dramas” over the course of her research. Westerners might characterize what the adults were doing in these cases as immature, often cruel pranks, even criminal acts of child abuse. What Briggs came to understand, however, was that the dramas served an important function in the context of Inuit culture. Tellingly, the provocations didn’t always involve rough treatment or incitements to conflict but often took the form of outrageous or disturbing lines of questioning. This approach is reflected in the title of Briggs’s chapter, “‘Why Don’t You Kill Your Baby Brother?’ The Dynamics of Peace in Canadian Inuit Camps.” However, even these gentler sessions were more interrogation than thought experiment, the clear goal being to arouse intense emotions in the children.

From interviews with adults in the communities hosting her, Briggs gleaned that the purpose of these dramas was to force children to learn how to handle difficult social situations. The term they used is isumaqsayuq, meaning “to cause thought,” which Briggs notes is a “central idea of Inuit socialization.” “More than that,” she goes on, “and as an integral part of thought, the dramas stimulate emotion.” The capacity for clear thinking in tense situations—and for not taking the tension too seriously—would help the children avoid potentially dangerous confrontations. Briggs writes:

The games were, themselves, models of conflict management through play. And when children learned to recognize the playful in particular dramas, people stopped playing those games with them. They stopped tormenting them. The children had learned to keep their own relationships smoother—to keep out of trouble, so to speak— and in doing so, they had learned to do their part in smoothing the relationships of others.3

The parents, in other words, were training the children, using simulated and age-calibrated dilemmas, to develop exactly the kind of equanimity and joking attitude they would need to mature into successful adults capable of maintaining a mostly peaceful society. They were prodding at the kids’ known sensitivities to teach them not to take themselves too seriously, because taking yourself too seriously makes you apt to take offense, and offense can often lead to violence.

Are censors justified in their efforts at protecting children from the wrong types of lessons?

The Inuit’s aversion to being at the center of any drama and their penchant for playfulness in potentially tense encounters are far removed from our own culture. Rather their approach to socialization relies on an insight that applies universally, one that’s frequently paid lip service in the West but even more frequently lost sight of. Anthropologist Margaret Mead captures the idea in her 1928 ethnography Coming of Age in Samoa, writing, “The children must be taught how to think, not what to think.”4 People fond of spouting this truism today usually intend to communicate something diametrically opposite to its actual meaning, with the suggestion being that anyone who accepts rival conclusions must have been duped by unscrupulous teachers. However, the crux of the insight is that education should not focus on conclusions at all. Thinking is not about memorizing and being able to recite facts and propositions. Thinking is a process. It relies on knowledge to be sure, but knowledge alone isn’t sufficient. It also requires skills.

Cognitive psychologists label knowing that and knowing how as declarative and procedural knowledge, respectively.5 Declarative knowledge can be imparted by the more knowledgeable to the less knowledgeable—the earth orbits the sun—but to develop procedural knowledge or skills you need practice. No matter how precisely you explain to someone what goes into riding a bike, for instance, that person has no chance of developing the requisite skills without at some point climbing on and pedaling. Skills require training, which to be effective must incorporate repetition and feedback.

What the Inuit understood, perhaps better than most other cultures, is that morality plays out far less in the realm of knowing what than in the realm of knowing how. The adults could simply lecture the children about the evils of getting embroiled in drama, but those children would still need to learn how to manage their own aggressive and retributive impulses. And explaining that the most effective method consists of reframing slights as jokes is fine, but no child can be expected to master the trick on first attempt. So it is with any moral proposition. We tell young children it’s good to share, for instance, but how easy is it for them to overcome their greedy impulses? And what happens when one moral precept runs up against another? It’s good to share a toy sword, but should you hand it over to someone you suspect may use it to hurt another child? Adults face moral dilemmas like this all the time. It’s wrong to cheat on your spouse, but what if your spouse is controlling and threatens to take your children if you file for divorce? It’s good to be honest, but should you lie to protect a friend? There’s no simple formula that applies to the entire panoply of moral dilemmas, and even if there were, it would demand herculean discipline to implement.

Unfortunately, Western children have a limited range of activities that provide them opportunities to develop their moral skillsets. Perhaps it’s testament to the strength of our identification with our own moral principles that few of us can abide approaches to moral education that are in any regard open-ended. Consider children’s literature. As I write, political conservatives in the U.S. are working to impose bans on books6 they deem inappropriate for school children. Meanwhile, more left-leaning citizens are being treated to PC bowdlerizations7 of a disconcertingly growing8 list of classic books. One side is worried about kids being indoctrinated with life-deranging notions about race and gender. The other is worried about wounding kids’ and older readers’ fragile psyches with words and phrases connoting the inferiority of some individual or group. What neither side appreciates is that stories can’t be reduced to a set of moral propositions, and that what children are taught is of far less consequence than what they practice.

Do children’s books really have anything in common with the playful dramas Briggs observed among the Inuit? What about the fictional stories adults in our culture enjoy? One obvious point of similarity is that stories tend to focus on conflict and feature high-stakes moral dilemmas. The main difference is that reading or watching a story entails passively witnessing the actions of others, as opposed to actively participating in the plots. Nonetheless, the principle of isumaqsayuq comes into play as we immerse ourselves in a good novel or movie. Stories, if they’re at all engaging, cause us to think. They also arouse intense emotions. But what could children and adults possibly be practicing when they read or watch stories? If audiences were simply trying to figure out how to work through the dilemmas faced by the protagonists, wouldn’t the outcome contrived by the author represent some kind of verdict, some kind of lesson? In that case, wouldn’t censors be justified in their efforts at protecting children from the wrong types of lessons?

To answer these questions, we must consider why humans are so readily held rapt by fictional narratives in the first place. If the events we’re witnessing aren’t real, why do we care enough to devote time and mental resources to them? The most popular stories, at least in Western societies, feature characters we favor engaging in some sort of struggle against characters we dislike—good guys versus bad guys. In his book Just Babies: The Origins of Good and Evil, psychologist Paul Bloom describes a series of experiments9 he conducted with his colleague Karen Wynn, along with their then graduate student Kiley Hamlin. They used what he calls “morality plays” to explore the moral development of infants. In one experiment, the researchers had the babies watch a simple puppet show in which a tiger rolls a ball to one rabbit and then to another. The first rabbit rolls the ball back to the tiger and a game ensues. But the second rabbit steals away with the ball at first opportunity. When later presented with both puppets and encouraged to reach for one to play with, the babies who had witnessed the exchanges showed a strong preference for the one who had played along. What this and several related studies show is that by as early as three months of age, infants start to prefer characters who are helpful and cooperative over those who are selfish and exploitative.

That such a preference would develop so early and so reliably in humans makes a good deal of sense in light of how deeply dependent each individual is on other members of society. Throughout evolutionary history, humans have had to cooperate to survive, but any proclivity toward cooperation left them vulnerable to exploitation. This gets us closer to the question of what we’re practicing when we enjoy fiction. In On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction, literary scholar Brian Boyd points out that animals’ play tends to focus on activities that help them develop the skills they’ll need to survive, typically involving behaviors like chasing, fleeing, and fighting. When it comes to what skills are most important for humans to acquire, Boyd explains:

Even more than other social species, we depend on information about others’ capacities, dispositions, intentions, actions, and reactions. Such “strategic information” catches our attention so forcefully that fiction can hold our interest, unlike almost anything else, for hours at a stretch.10

Fiction, then, can be viewed as a type of imaginative play that activates many of the same evolved cognitive mechanisms as gossip, but without any real-world stakes. This means that when we’re consuming fiction, we’re not necessarily practicing to develop equanimity in stressful circumstances as do the Inuit; we’re rather honing our skills at assessing people’s proclivities and weighing their potential contributions to our group. Stories, in other words, activate our instinct, while helping us to develop the underlying skillset, for monitoring people for signals of selfish or altruistic tendencies. The result of this type of play would be an increased capacity for cooperation, including an improved ability to recognize and sanction individuals who take advantage of cooperative norms without contributing their fair share.

Ethnographic research into this theory of storytelling is still in its infancy, but the anthropologist Daniel Smith and his colleagues have conducted an intensive study11 of the role of stories among the Agta, a hunter-gatherer population in the Philippines. They found that 70 percent of the Agta stories they collected feature characters who face some type of social dilemma or moral decision, a theme that appears roughly twice as often as interactions with nature, the next most common topic. It turned out, though, that separate groups of Agta invested varying levels of time and energy in storytelling. The researchers saw this as an opportunity to see what the impact of a greater commitment to stories might be. In line with the evolutionary account laid out by Boyd and others, the groups that valued storytelling more outperformed the other groups in economic games that demand cooperation among the players. This would mean that storytelling improves group cohesion and coordination, which would likely provide a major advantage in any competition with rival groups. A third important finding from this study is that the people in these groups knew who the best storytellers were, and they preferred to work with these talented individuals on cooperative endeavors, including marriage and childrearing. This has obvious evolutionary implications.

What do children learn from parents’ concern that single words may harm or corrupt them?

Remarkably, the same dynamics at play in so many Agta tales are also prominent in classic Western literature. When literary scholar Joseph Carroll and his team surveyed thousands of readers’ responses to characters in 200 novels from authors like Jane Austen and Charles Dickens, they found that people see in them the basic dichotomy between altruists and selfish actors. They write:

Antagonists virtually personify Social Dominance—the self-interested pursuit of wealth, prestige, and power. In these novels, those ambitions are sharply segregated from prosocial and culturally acquisitive dispositions. Antagonists are not only selfish and unfriendly but also undisciplined, emotionally unstable, and intellectually dull. Protagonists, in contrast, display motive dispositions and personality traits that exemplify strong personal development and healthy social adjustment. They are agreeable, conscientious, emotionally stable, and open to experience.12

Interestingly, openness to experience may be only loosely connected to cooperativeness and altruism, just as humor is only tangentially related to peacefulness among the Inuit. However, being curious and open-minded ought to open the door to the appreciation of myriad forms of art, including different types of literature, leading to a virtuous cycle. So, the evolutionary theory, while focusing on cooperation, leaves ample room for other themes, depending on the cultural values of the storytellers.

In a narrow sense then, cooperation is what many, perhaps most, stories are about, and our interest in them depends to some degree on our attraction to more cooperative, less selfish, individuals. We obsessively track the behavior of our fellow humans because our choices of who to trust and who to team up with are some of the most consequential in our lives. This monitoring compulsion is so powerful that it can be triggered by opportunities to observe key elements of people’s behavior—what they do when they don’t know they’re being watched—even when those people don’t exist in the real world. But what keeps us reading or watching once we’ve made our choices of which characters to root for? And, if one of the functions of stories is to help us improve our social abilities, what mechanism provides the feedback necessary for such training to be effective?

In Comeuppance: Costly Signaling, Altruistic Punishment, and Other Biological Components of Fiction, literary scholar William Flesch theorizes that our moment-by-moment absorption in fictional plots can be attributed to our desire to see cooperators rewarded and exploiters punished. Citing experiments that showed participants were willing to punish people they had observed cheating other participants—even when the punishment came at a cost13 to the punishers— Flesch argues that stories offer us opportunities to demonstrate our own impulse to enforce norms of fair play. Within groups, individual members will naturally return tit for tat when they’ve been mistreated. For a norm of mutual trust to take hold, however, uninvolved third parties must also be willing to step in to sanction violators. Flesch calls these third-party players “strong reciprocators” because they respond to actions that aren’t directed at them personally. He explains that

the strong reciprocator punishes or rewards others for their behavior toward any member of the social group, and not just or primarily for their individual interactions with the reciprocator.14

His insight here is that we don’t merely attend to people’s behavior in search of clues to their disposition. We also watch to make sure good and bad alike get their just deserts. And the fact that we can’t interfere in the unfolding of a fictional plot doesn’t prevent us from feeling that we should. Sitting on the edge of your seat, according to this theory, is evidence of your readiness to step in.

Another key insight emerging from Flesch’s work is that humans don’t merely monitor each other’s behavior. Rather, since they know others are constantly monitoring them, they also make a point of signaling that they possess desired traits, including a disposition toward enforcing cooperative norms. Here we have another clue to why we care about fictional characters and their fates. It doesn’t matter that a story is fictional if a central reason for liking it is to signal to others that we’re the type of person who likes the type of person portrayed in that story. Reading tends to be a solitary endeavor, but the meaning of a given story paradoxically depends in large part on the social context in which it’s discussed. We can develop one-on-one relationships with fictional characters for sure, but part of the enjoyment we get from these relationships comes from sharing our enthusiasm and admiration with nonfictional others.

This brings us back to the question of where feedback comes into the social training we get from fiction. One feedback mechanism relies on the comprehensibility and plausibility of the plot. If a character’s behavior strikes us as arbitrary or counter to their personality as we’ve assessed it, then we’re forced to think back and reassess our initial impressions—or else dismiss the story as poorly conceived. A character’s personality offers us a chance to make predictions, and the plot either confirms or disproves them. However, Flesch’s work points to another type of feedback that’s just as important. The children at the center of Inuit playful dramas receive feedback from the adults in the form of laughter and mockery. They learn that if they take the dramas too seriously and thus get agitated, then they can expect to be ridiculed. Likewise, when we read or watch fiction, we gauge other audience members’ reactions, including their reactions to our own reactions, to see if those responses correspond with the image of ourselves we want to project. In other words, we can try on traits and aspects of an identity by expressing our passion for fictional characters who embody them. The outcome of such experimentation isn’t determined solely by how well the identity suits the individual fan, but also by how well that identity fits within the wider social group.

Parents worried that their children’s minds are being hijacked by ideologues will hardly be comforted by the suggestion that teachers and peers mitigate the impact of any book they read. Nor will those worried that their children are being inculcated with more or less subtle forms of bigotry find much reassurance in the idea that we’re given to modeling15 our own behavior on that of the fictional characters we admire. Consider, however, the feedback children receive from parents who respond to the mere presence of a book in a school library with outrage. What do children learn from parents’ concern that single words may harm or corrupt them?

Today, against a backdrop of increasing vigilance and protectiveness among parents, kids are graduating high school and moving on to college or the workforce with historically unprecedented rates of depression16 and anxiety,17 having had far fewer risky but rewarding experiences18 such as dating, drinking alcohol, getting a driver’s license, and working for pay. It’s almost as though the parents who should be helping kids learn to work through difficult situations by adopting a playful attitude have themselves become so paranoid and humorless that the only lesson they manage to impart is that the world is a dangerous place, one young adults with their fragile psyches can’t be trusted to navigate on their own.

Parents should, however, take some comfort from the discovery that even pre-verbal infants are able to pick out the good guys from the bad. As much as young Harry Potter fans discuss which Hogwarts House the Sorting Hat would place them in, you don’t hear19 many of them talking enthusiastically about how cool it was when Voldemort killed all those filthy Muggles. The other thing to keep in mind is that while some students may embrace the themes of a book just because the teacher assigned it, others will reject them for the same reason. It depends on the temperament of the child and the social group they hope to achieve status in.

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 28.3

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Download our app

Should parents let their kids read just anything? We must acknowledge that books, like playful dramas, need to be calibrated to the maturity levels of the readers. However, banning books deemed dangerous deprives children not only of a new perspective. It deprives them of an opportunity to train themselves for the difficulties they’ll face in the upcoming stages of their lives. If you’re worried your child might take the wrong message from a story, you can make sure you’re around to provide some of your own feedback on their responses. Maybe you could even introduce other books to them with themes you find more congenial. Should we censor words or images—or cease publication of entire books—that denigrate individuals or groups? Only if we believe children will grow up in a world without denigration. Do you want your children’s first encounter with life’s ugliness to occur in the wild, as it were, or as they sit next to you with a book spread over your laps?

What should we do with great works by authors guilty of terrible acts? What about mostly good characters who sometimes behave badly? What happens when the bad guy starts to seem a little too cool? These are all great prompts for causing thought and arousing emotions. Why would we want to take these training opportunities away from our kids? It’s undeniable that books and teachers and fellow students and, yes, even parents themselves really do influence children to some degree. That influence, however, may not always be in the intended direction. Parents who devote more time and attention to their children’s socialization can probably improve their chances of achieving desirable ends. However, it’s also true that the most predictable result of any effort at exerting complete control over children’s moral education is that their social development will be stunted. ![]()

About the Author

Dennis J. Junk holds degrees in anthropology and psychology and a Masters in British and American literature. His first book is He Borara: a Novel about an Anthropologist among the Yąnomamö.

References

- https://rb.gy/hjcpn

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Mead, M. (1928). Coming of Age in Samoa. William Morrow and Co.

- https://rb.gy/i7a0h

- https://rb.gy/sx5oh

- https://rb.gy/wq45k

- https://rb.gy/6vi33

- https://rb.gy/6w2nt

- Boyd, B. (2010). On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction. Belknap Press.

- https://rb.gy/n3sxn

- Carroll, J., Gottschall, J., Johnson, J.A., & Kruger, D. (2012). Graphing Jane Austen: The Evolutionary Basis of Literary Meaning. Palgrave Macmillan.

- https://rb.gy/1az75

- Flesch, W. (2008). Comeuppance: Costly Signaling, Altruistic Punishment, and Other Biological Components of Fiction. Harvard University Press.

- https://rb.gy/dw9gt

- https://rb.gy/jgaf2

- https://rb.gy/c3gs4

- https://rb.gy/hejk8

- Vezalli, L., Stathi, S., Giovannini, D., Cappoza, D. & Trifiletti, E. (2014). The Greatest Magic of Harry Potter: Reducing Prejudice. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 45(2), 105–121.

This article was published on December 13, 2023.