You can’t keep a bad idea down. Bury it in here, and it pops out over there. Drive a stake through its shriveled heart, and it sprouts three more arms and four new toes.

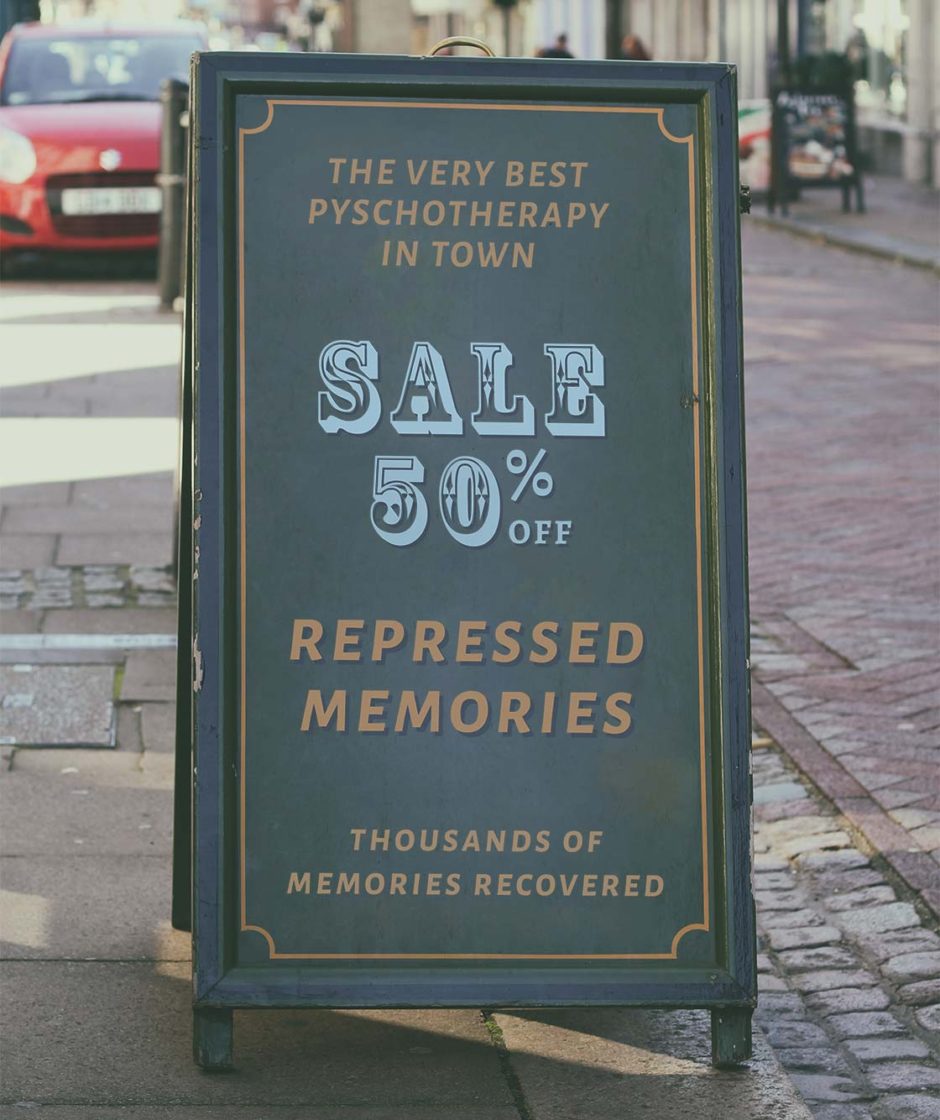

Are you old enough to have a memory of the memory wars? They were sparked by a debate that began more than 30 years ago, raging at a fever heat during the 1990s, dividing along a key issue: Do people commonly “repress” their memories of traumatic experiences, memories that can then be “recovered” in therapy, often with the help of hypnosis, dream analysis, and other probing techniques?

Yes they do, claimed many psychotherapists, and they testified to that effect in hundreds of court cases in which an adult came to remember, usually in therapy, having been sexually abused years earlier by a parent, teacher, or neighbor.

No they don’t, replied most psychological scientists, whose experimental research demonstrated the power of therapeutic suggestion in creating memories that often grew in implausibility. The problem for many people who have undergone a traumatic experience, they said, is not that they forget what happened to them, but that they cannot forget; memories intrude in waking life and nightmares. Richard McNally, a clinical scientist and professor at Harvard, reviewed the evidence in his book Remembering Trauma, and famously concluded: “The notion that the mind protects itself by repressing or dissociating memories of trauma, rendering them inaccessible to awareness, is a piece of psychiatric folklore devoid of convincing empirical support.”1

By the early 2000s, with the recovered-memory movement in disarray due to successful malpractice suits against some of its most egregious proponents and to the overturning of many (but not enough) wrongful convictions of parents and teachers, it seemed that the wars had subsided, that science was vindicated. I hear the gentle hum of skeptics, muttering: Ha. We all know how many ideas that are “devoid of convincing empirical support” will float along indefinitely once they have a vocal contingency believing in them — and profiting from them.

Today, at least, the majority of scientifically trained clinical psychologists — especially cognitive-behavioral therapists — no longer believe that traumatic memories are “dissociated” from the rest of the mind and repressed from consciousness, awaiting special therapeutic techniques that can accurately uproot them. Unfortunately, these beliefs are still widely held by general, nonresearch-oriented practitioners (notably hypnotherapists, psychoanalysts, neurolinguistic programming therapists, and internal family systems therapists), the public, and Gen Z college students.2

I suspect that the persistence of repression is fed by the current cultural focus on victims of all kinds, and the belief that rape and other forms of sexual abuse and coercion are epidemic. After all, if we are in the midst of an epidemic, what are we to make of the many people who claim they were abused but can’t actually remember what happened? Enter repression, in the form of the old discredited claim that “if you don’t remember it, that is actually evidence that you were abused — it was so traumatic that you repressed the memory.” Today this justification is fed by an immense trauma-and-recovery industry of therapists, healers, counselors, and law enforcement professionals, to say nothing of the self-defined experts who run training workshops for all of them, usually knowing little or nothing about psychological science.

The nub of the issue is the blurring of repression with ordinary forgetting. Everyone forgets and later recalls all kinds of events, but that doesn’t mean the brain “repressed” those memories.

In a recent paper reviewing key controversies about memory and trauma, Iris M. Engelhard of Utrecht University, Richard McNally of Harvard, and Kevin van Shie of Erasmus University in Rotterdam observed that proponents of the repression school have tended to conflate other, normal memory processes to support their view. “For example,” write Engelhard et al., “they misinterpreted ordinary forgetfulness as an inability to recall trauma, confused organic amnesia with psychic repression, cited reluctance to disclose one’s trauma with an inability to recall it, and confused not thinking about sexual abuse for a long time with an inability to remember it.”3

That’s the nub of the issue: the blurring of repression with ordinary forgetting. Everyone forgets and later recalls all kinds of events, including painful ones, but that doesn’t mean some little part of the brain “repressed” memories that were unusually distressing. No memory researcher believes that all recovered memories are false; many can indeed be accurate. Most of us can recall experiences that we simply hadn’t thought about for many years, especially when cues in the immediate setting evoke them. But because our current beliefs shape what we remember and how we interpret those memories, an experience we might now define as traumatic might, at the time, have merely been unpleasant or unsettling.

In his paper “True and false recovered memories: Toward a reconciliation of the debate,” McNally describes one of his studies in which some participants recalled one or more episodes of “fondling by a trusted person who neither threatened nor physically harmed them when they were about 7 years old.” They said they felt confused, disgusted, or anxious as a child, but not terrified — the most memorable emotion in a traumatic event. Because they did not interpret the experience at the time as being sexually abusive, they put it out of their minds, not thinking about it for years. Only when they encountered reminders were they able to recall the event readily.4

We are all constantly rewriting and reevaluating our histories in light of what our peers and our culture now tell us was amoral, dangerous, foolish, or reprehensible.

This finding infuriates many trauma-victim activists, who assume that any unwanted or unpleasant sexual experience, especially in childhood, must be traumatic, even if the victim doesn’t think so. They are wrong. Many people can recall upsetting, even ugly events yet do not interpret them as life-shattering traumas. Moreover, the fact that a person does not regard a past experience as being traumatic does not mean the experience was justified or acceptable — morally, legally, or psychologically. We are all constantly rewriting and reevaluating our histories in light of what our peers and our culture now tell us was amoral, dangerous, foolish, or reprehensible.

But when an entire industry of experts claims to know what a trauma is and that you are suffering from it even if you don’t think so, we are into different territory — indeed, we’ve gone back to the future of the 1990s. In her brilliant 2017 piece for the Atlantic, Emily Yoffe blew the whistle on the rise and institutionalization of “trauma-informed” investigations, a method designed originally to guide counselors who were helping people known to have suffered shattering, life-threatening events.5 Unfortunately, that worthy goal soon morphed into a zealous effort to catch more and more people in their net, by expanding the range of symptoms said to indicate a person has been traumatized. This past May, a campus due-process organization called Families Advocating for Campus Equality (FACE) identified some of the major scientific flaws in these investigations:

- the promotion of unsupported claims such as “tonic immobility” — the idea that when people are threatened, as by sexual coercion, they freeze and cannot protest or escape (this phenomenon, noted Yoffe, is at least true of chickens);

- the presumption that if an accuser cannot remember the alleged trauma in question, it’s because she was traumatized, rather than drunk or suffering an alcohol-induced blackout;

- the failure to consider the vulnerability of accusers to post-event interpretations by their friends and victim advocates.6

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 24.3

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

The main reasoning flaw committed by “trauma-informed” investigators is the oldest in the book: They regard anything the alleged victim does or recalls as being “consistent with abuse happened.” Did she freeze or run? Were her memories fragmented or not, delayed or not, vivid or not, remembered or not? All are assumed to confirm abuse. But just as people have varied responses to being robbed, being hit by a parent or partner, or surviving a disaster, there is no “one size fits all victims.” Investigators, in their effort to identify that one size, often confuse cause and consequence. They can say, “If trauma, then variety of symptoms and memory impairments may ensue,” but not their more common mistake, “If variety of symptoms and impaired memories, then we know abuse has occurred.”

And so the past is present. Unscientific and often pernicious beliefs about memory, trauma, and recovery — declining among most psychotherapists — are ascendant among “trauma informed” practitioners. Now as then, the goal is not only to find the truth in a given legal dispute, and not only to better help people who actually have survived rape and other devastating events, but to generate more victims in need of treatment. It looks like there will always be plenty of them. ![]()

About the Author

Dr. Carol Tavris is a social psychologist and coauthor, with Elliot Aronson, of Mistakes Were Made (but Not by Me): Why We Justify Foolish Beliefs, Bad Decisions, and Hurtful Acts. Watch the recording of Science Salon # 10 in which Tavris, in a dialogue with Michael Shermer, explores cognitive dissonance and what happens when we make mistakes, cling to outdated attitudes, or mistreat other people. Read I, Too, Am Thinking About Me, Too in which Tavris reminds us that it is more important than ever to tolerate complexity and ask questions that evoke cognitive dissonance whenever a movement is fueled by rage and revenge. Read Please Touch in which Tavris reminds us that the human need for touch is significant.

References

- McNally, Richard J. 2003. Remembering Trauma. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Patihis, Lawrence, Lavina Y. Ho, Ian W. Tingen, Scott O. Lilienfeld, and Elizabeth Loftus. “Are the ‘Memory Wars’ Over? A Scientist-Practitioner Gap in Beliefs About Repressed Memory. Psychological Science, 25, 519-530.

- Engelhard, Iris M., Richard J. McNally, and Kevin van Schie. 2019. “Retrieving and Modifying Traumatic Memories: Recent Research Relevant to Three Controversies.” Current Directions in Psychological Science, Vol. 28(1) 91-96.

- McNally, Richard J. “Searching for Repressed Memory.” In R. F. Belli (ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Vol. 58. True and false recovered memories: Toward a reconciliation of the debate. New York: Springer.

- Yoffe, Emily. 2017. “The Bad Science Behind Campus Response to Sexual Assault.” The Atlantic, Sept. 8.

-

https://bit.ly/2WSB2Ep

https://bit.ly/2WM1R1A

This article was published on October 15, 2019.

I am old enough to remember the memory wars and am an admirer of Dr. Loftus and others for their bravery in confronting these issues (in the face of death threats I understand). I admire Dr. Tavris’s work as well. I do want to address the first bulleted statement in Dr. Tavris’s article referencing a press release (referenced in the article as https://bit.ly/2WM1R1A); the press release refers to an article on the Families Advocating for Campus Equality (FACE) website (https://www.facecampusequality.org/library) “Trauma-Informed Theories Disguised as Evidence” by Cynthia P. Garrett .

The first bullet states that one of the major scientific flaws in the FACE article/investigation is “the promotion of unsupported claims such as ‘tonic immobility’.” This is misleading as it suggests that tonic immobility is itself scientifically flawed or an unsupported claim. There is a healthy body of research in this area pertaining to humans, though it is still new as these things go. As in many neurobiological studies this research can be misused, overstated, oversimplified, and prematurely applied beyond the scope of its findings. Indeed, the press release and the article state and suggest that tonic immobility is being Illogically applied to situations that are not life-threatening – not that tonic immobility is itself a flawed concept.

Misusing findings from research to promote political or economic gain is nothing new, but it doesn’t mean the findings are in error – just the people and causes misusing them.

I agree with above post (Tzindaro).

The use of leading questions to induce memories of abuse to be used in courtrooms is highly dubious.

But the dismissal of the repressed memories per se is in itself dubious.Yes, one can say that a person memory can be shaped by society’s norms is valid but that’s taking one aspect separate from the whole picture which is that the element of repression is active in most abuse victims and is expressed via different coping mechanisms over time.

So, instead of focusing on one aspect like memory and go binary in order to approve or disapprove a thesis is narrow minded.Therapists dealing with the complexity involved in treatments of abuse victims know that.

It seems to me that mrs Tavris is a tad overeager to press the dismissal button.I wonder why..

That SOME memories can SOMETIMES be repressed and later recovered does not mean ALL claims of recovered memories are reliable enough to be used in criminal courts. I see no conflict between use of the concept in the therapists office while demanding independent evidence in the courtroom.

My take on it is that recovered memories are a valid concept and should be regarded as an important part of individual treatment, but should never be allowed in a criminal trial. Throwing out the idea because of misuse by lawyers and the gullibility of judges in the heavily politicised American legal system is not warranted. It is the legal system that is the problem, not the claims.

Here are some interesting developments that tend to agree with Tavris (both papers led by Otgaar et al.):

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1745691619862306

and

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336552070_Belief_in_Unconscious_Repressed_Memory_Is_Widespread_A_Comment_on_Brewin_Li_Ntarantana_Unsworth_and_McNeilis_in_press