“We suffer more in imagination than in reality.”

A young woman is walking down a crowded street when she suddenly feels a pain in her wrist accompanied by dizziness and believes she is the victim of a syringe attack from a passer-by.1 Another woman is out at a popular South London nightspot. After dancing with a stranger who offers to buy her a drink, she refuses, and they soon part company. Before long, she feels a prickling sensation on her arm but pays little notice. Later she becomes dizzy and passes out. The press latches onto the incident as a needle attack. One headline proclaims: “Waitress Doped by Stranger at Bar.”2 Over the past year, scores of similar cases have been reported across Europe, mainly in British and French nightclubs. However, the above incidents happened nearly a century ago when waves of similar cases were recorded throughout North America and Europe. During both periods, the attacker melted into the shadows and was never caught in the act.

A fascinating aspect of social panics is that they often recur throughout history. The names and the places may have changed, but the same patterns reappear. The most recent wave began in the spring of 2021 when alarming reports of needle attacks started to appear across Great Britain, where police have logged over 1,300 cases.3 In recent months, French authorities have recorded at least 300 incidents.4 Conspicuously, there is yet to be a single confirmed case or conviction. The typical victim is a young woman out clubbing with friends when she feels lightheaded after drinking a modest amount of alcohol. She would feel faint or pass out and be taken home or to a hospital. The next day, she has trouble recalling the previous night’s events. Then, after hearing suggestions that she may have been stuck with a syringe, she scrutinizes her body for evidence of an attack and finds vague signs confirming her suspicions: a scratch, bruise, bump or blemish that is assumed to be an injection site. The panic began amidst sensational British media reports describing a few high-profile cases and calling for more victims to come forward, prompting a deluge of social media posts. As more and more women shared their experiences, including photos of suspected puncture marks, there was a public outcry for police to do more, generating even more media reports. Police data provided to a 2022 inquiry in the UK House of Commons revealed that most “victims” were female (88 percent), between the ages of 18 and 21 (73 percent), and the majority of incidents occurred at clubs and pubs (93 percent).5

Red Flags and Faulty Memories

There are many reasons for skepticism. To stick someone with a needle while clubbing with friends—and without anyone realizing, defies credulity. Dr. Adam Winstock, a British psychiatrist specializing in addiction, observes that to be able to inject someone in a dark club through the victim’s clothing would be highly challenging, as would be keeping the needle in the victim long enough to administer the drug.6 Forensic toxicologist John Slaughter concurs, noting that injecting someone without their knowledge would be incredibly difficult.7 Another red flag involves the array of reported symptoms. Soon after reports of “spiking” began to emerge, one British tabloid published a list of indicators that someone has been spiked. They include confusion, loss of balance, vision problems, nausea, vomiting, feeling “drunker” than expected, and losing consciousness. The problem is that these symptoms are indistinguishable from being intoxicated.8 In January, the head of emergency services for Britain’s National Health Service, Dr. Adrian Boyle, told a UK government inquiry that in most cases when suspected spike victims were examined in emergency rooms, no sedatives were found in their system. In cases where drugs were present, most were prescriptions. In one suspected victim, tests revealed the presence of GHB, a central nervous system depressant used to treat sleep disorders. It causes drowsiness, reduces heart rate, and can be dangerous if misused. Yet, it is so thick and viscous that it would be very difficult to inject.9

Thanks to decades of memory and cognition research, it is well-known that human recall of even recent events is notoriously unreliable. Before their attack, many victims admitted that they had been drinking but were adamant that they were not inebriated. However, a study of suspected drink-spiking in Australia found that people often underestimate the amount of alcohol they consume. In one instance, a 17-year-old girl was rushed to the hospital after drinking a single glass of vodka—or so she said. Upon further questioning, she recalled also drinking beer and whisky. The study analyzed blood and urine samples of 97 patients who presented at hospital emergency departments. Not one had any traces of sedatives.10 Another study examined 75 primarily female patients who presented at a hospital casualty ward in Wales and told doctors their drinks had been spiked while at a local club or bar. Researchers found no evidence that any of the women had consumed spiked beverages. Twenty percent had recreational drugs in their system, while nearly two-thirds had been drinking excessively.11 The lead researcher, emergency room physician Dr. Hywel Hughes, observed that claiming their drink was spiked may be used as an excuse by embarrassed patients after becoming incapacitated from a night of binge drinking. Local physician Dr. Peter Saul concurred: “There had always been a suspicion that people would say that their drinks had been spiked when perhaps they had misjudged how much alcohol they were taking. If you go home and your parents are there, and you are vomiting on the path…you get sympathy if you say, ‘My drink was spiked.’ You don’t get sympathy if you say, ‘We spent too long in the bar.’”12

Social panics involve imaginary or exaggerated threats to society by nefarious individuals or groups. Historical scapegoats include witches, Jews, Communists, foreigners, and homosexuals. Outbreaks are often triggered by a sensational media report that receives saturation coverage. A major figure in the needle-spiking panic is Sarah Buckle. The young Nottingham University student was clubbing with friends on the night of September 28, 2021, when she passed out—only to wake up in the hospital with no recall of the previous night. After an uneventful evening, she said: “I started being sick all over myself, and my friends could sense something was wrong.” A young woman vomiting during a night out on the town with friends is not unusual. In a later interview, she appears to indicate that she had imbibed a significant amount of alcohol, telling a journalist that she “wasn’t intoxicated on a stupid level or overly drunk.”13 She only considered the possibility of having been “spiked” after it was mentioned by attending medical personnel. That’s when she noticed discoloration on her left hand and a mark resembling a tiny pinprick.14

A Crime in Search of Criminals

Reports of needle-spiking have been spreading throughout mainland Europe in recent months. On May 4, 2022, eighteen-year-old Tomas Laux attended a rap concert in Lille, Northern France. After drinking alcohol and smoking marijuana, he became dizzy and had a headache. He also noticed a mysterious bruise and what appeared to be a puncture mark on his arm. The next day, still feeling unwell, Laux sought medical treatment and was told there was evidence of a needle prick. Tests for HIV and hepatitis were negative. Incidents like this have prompted French authorities to intensify efforts to capture those believed responsible. The French Interior Ministry recently launched a national campaign to raise awareness of the issue by distributing warning leaflets to clubbers. Despite the hundreds of reports, no arrests have been made, no needles have been found, and no motive has been established.15

Similar needle-spiking incidents have been reported in other parts of Western Europe. At a street party near Kaatsheuvel, the Netherlands, on Saturday, April 21, six people presented to a first-aid post reporting that they believed they had been spiked with a needle.16 On the same day in Mechelen, Belgium, a group of soccer supporters began experiencing mysterious symptoms during a match. It started when a young woman collapsed and was taken away by emergency services. Soon after, more women followed suit. In all, fourteen people at the match were taken ill. Media reports blamed needle attacks. One newspaper headline read: “Syringe Spiking: 14 people attacked…” Yet of the eight people brought to the hospital, none had drugs in their system.17 The situation escalated a few days later when 24 teenage girls developed headaches, nausea, and breathing problems at a festival in Hasselt, Belgium. Several victims said they felt a prick before their symptoms developed. An unnamed witness said, “We heard that a woman had fallen from a drug syringe, and then we saw several other people fall.” The festival was halted, and more than 3,000 attendees were evacuated. Ten of the victims were taken to the hospital as a precautionary measure. Four girls had their urine tested for drugs; the results were negative.18

The Historical Backdrop

Needle-spiking panics have been occurring for more than a century. There was a major poison needle scare in the United States in 1914. Young women would feel a stinging sensation in their arm while at a theatre or other public place, then suddenly start to feel dizzy. It was believed that they had been injected with a powerful narcotic, and that as the drug began to take effect, the malefactor would step in to help and guide the victim to a waiting cab where they would be whisked away to some sinister fate.19 Similar panics occurred in the UK throughout the 1920s and 1930s. In 1932, there were so many reports that police suspected there was a drugging gang at work in London, employing both men and women to inject and then kidnap young girls.20 In fact, “drug needle attacks,” as the tabloids called them, were seen as such a growing evil that Scotland Yard considered employing plain clothes female officers to try and catch the culprits. There were hundreds of reported attacks in the first half of 1932 alone.21

Social panics arise in an atmosphere of fear and uncertainty. It may be no coincidence that the spiking epidemic has coincided with the easing of pandemic restrictions. British nightclubs had only just returned to normal in the summer of 2021, after two years of isolation and disrupted routines. Bombarded with frightening news reports about COVID, as clubs reopened there was still a fear of the virus and guilt associated with the possibility that one might catch it and then pass it on to vulnerable loved ones. The needle, an object of fear for many, may represent anxiety about vaccinations and fear of contamination.

The mythical evil needle-spiker preying on vulnerable women joins a long list of panics involving phantom assailants that have terrorized communities for centuries: Spring Heeled Jack (1837–38); the French hatpin stabber of 1923: the “mad gasser” of Mattoon, Illinois (1944); and the phantom slasher of Taipei (1956); even the recent claims of sonic or microwave attacks on U.S. embassy staff in Cuba and around the world. These are but a few examples.22, 23

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 27.3

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Download our app

Social media posts have added a new twist to the panic—reports of women being intentionally spiked with an HIV-contaminated needle. In some of these stories, the woman regains consciousness only to find a note in her pocket telling her she has HIV and later tests positive. This is a new version of a classic 1980s urban legend: “AIDS Mary,” where the victim awakens after a one-night stand to find the words: “Welcome to the world of AIDS” written in lipstick scribbled on the bedroom mirror.

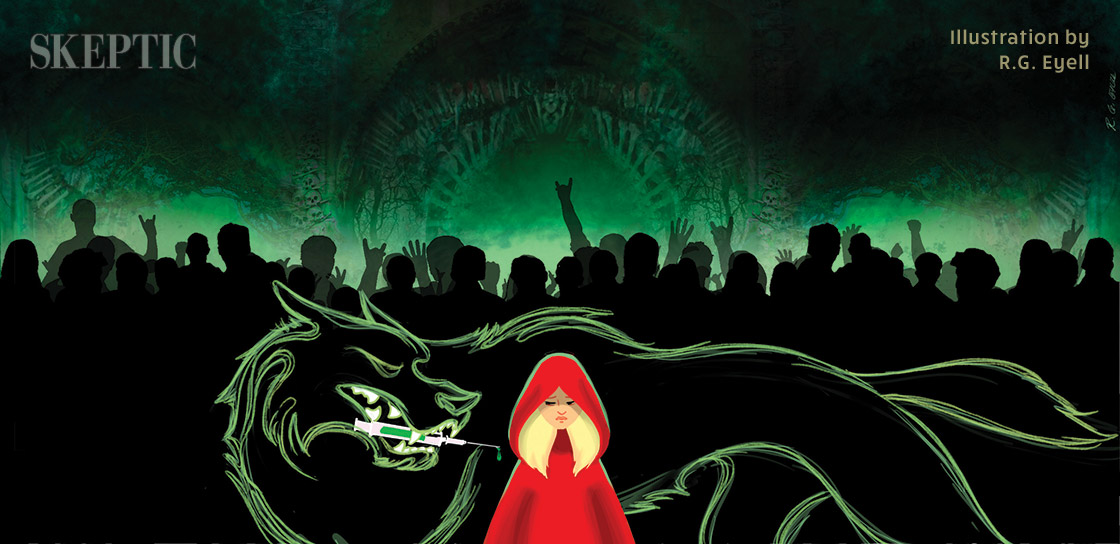

The needle-spiking panic may function as a cautionary tale. Similar panics keep re-emerging throughout history, only the particulars change to reflect current fears. The night club takes the place of the scary forest; the syringe-wielding maniac, the Big Bad Wolf. And we all know what happens to young girls who don’t heed the warnings and stray from the path. ![]()

About the Authors

Robert E. Bartholomew is an Honorary Senior Lecturer in the Department of Psychological Medicine at the University of Auckland in New Zealand. He has written numerous books on the margins of science covering UFOs, haunted houses, Bigfoot, lake monsters—all from a perspective of mainstream science. He has lived with the Malay people in Malaysia, and Aborigines in Central Australia. He is the co-author of two seminal books: Outbreak! The Encyclopedia of Extraordinary Social Behavior with Hilary Evans, and Havana Syndrome with Robert Baloh.

Paul Weatherhead resides in West Yorkshire, England, where he teaches international students research skills and critical thinking. His book, Weird Calderdale, takes a skeptical approach to classic cases of UFO abduction, ghosts, and phantom attacker cases in West Yorkshire. He is also a musician playing electric mandolin with the cult folk-rock group “The Ukrainians.”

References

- …Epidemic of Imaginary Outrages. The Poisoned Needle. (1914, April 14). Manchester Evening News, 6.

- …Waitress Doped by Stranger at Bar. (January 27, 1932). Daily Herald (London), 9.

- https://bit.ly/3AhdwYK

- https://bit.ly/3NIJFfa

- https://bit.ly/3nw2MhJ

- https://bbc.in/3a4DHHs

- https://bit.ly/3R5aw7K

- https://bit.ly/3AfGVTn

- https://bit.ly/3AhnGIY

- https://bit.ly/3Ahs1vE

- https://bit.ly/3QYWlRM

- https://bit.ly/3NBBctO

- https://bit.ly/3I4gZMp

- https://bit.ly/3nuGfSe

- https://bit.ly/3QYXTLA

- https://bit.ly/3uggPf0

- https://bit.ly/3bIhfEp

- https://bit.ly/3NEohYa

- …Epidemic of Imaginary Outrages. The Poisoned Needle. (1914, April 14). Manchester Evening News, 6.

- Drugging-Gang Attacks Girls. (1932, January 27). Daily Herald, 9.

- Girls’ Peril from Drug-Needle Attacks in the Street… (1932, March 6). The People.

- Evans, H., & Bartholomew, R. (2009). Outbreak: The Encyclopedia of Extraordinary Social Behavior. Anomalist Books.

- Baloh, R.W., & Bartholomew, R. (2020). Havana Syndrome. Copernicus Books.

This article was published on January 17, 2023.